Grace Through Grief: A Shattered Family Recovers

This intimate seven-part print and multimedia series tells the story of Arturo Martinez, who suffered life-threatening injuries after an intruder broke into his house and sexually assaulted and murdered his wife and daughter while the rest of the family slept. Judges called "Grace Through Grief" a “deeply reported and inspiring portrayal of a family in the aftermath of horror.” Originally published in the Las Vegas Sun in April, 2013.

Chapter One: Sleeping with Angels, Awakening to a Nightmare

In an older, one-story home at 1016 Robin St. lives a family of five — six if you count the puppy.

They have chores to do, places to go on this Saturday, April 14, 2012.

This will be the family’s last day together.

Yadira Martinez cuts her 9-year-old son Cristopher’s hair. He has religion class in the morning, a rite of passage for any Catholic youngster. Later, Yadira drives Cristopher and her oldest child, 10-year-old Karla, to their acting class. Her husband, Arturo, an electrician, takes their little one, Alejandro, 4, with him to the supermarket.

The family gathers in the evening at their friends’ house. On TV, the adults watch Juan Manuel Marquez box his way to a unanimous-decision victory over Sergey Fedchenko while the kids hunker down in another room, glued to a PlayStation.

A guitar comes out next. Yady, as her husband affectionately calls her, slides onto Arturo’s lap as he strums the guitar and softly sings one of her favorite songs, “Romeo y Julieta,” a take on the Shakespeare tale by Joan Sebastian, a popular Mexican musician. Translated into English, it begins:

They told me the story of Romeo and Juliet

And I thought, “What a beautiful story,”

And now it turns out

That this, what I feel for you

Is bigger and more beautiful

Arturo repeats the song four times, buoyed by the spirit of the moment. By now, it’s past midnight. Friends invite them to stay the night, but Arturo and Yady kindly decline. It would be an imposition. Too many people.

They pile into their red Ford Escape and drive home. The children and Yady go to bed; Arturo remains in the family room to watch TV.

“We’ll see you guys tomorrow,” he says, growing very drowsy.

His wife replies for all to hear, uttering her signature bedtime wish.

“Goodnight. Sleep with angels.”

•••

What happens overnight is all but impossible to piece together. And the survivors might be better off not knowing.

The allergy-ridden 4-year-old sleeps in his big brother’s room, which he does frequently, and in the morning sneezes, startling Cristopher awake.

Cristopher creeps out of bed to get his brother a tissue from the bathroom. As he opens his partially closed bedroom door, he finds blood covering the hallway’s tiled floor. Someone, he thinks, must have had a bloody nose.

As Cristopher walks down the hallway, he turns to his left and sees his father, on the other side of the house, standing near the master bedroom door. On the floor is the boys’ mother, naked from the waist down and surrounded by blood.

Bewildered, Cristopher gets the tissue and steps back toward his bedroom as the two most logical words enter his head: What happened?

He leaves Alejandro with the tissue and walks down the hall to his sister’s bedroom. He stops at the doorway, frozen by what he sees: Karla is lying in a pool of blood on her bedroom floor and, like their mother, is naked from the waist down, stripped of the pink, polka-dot pajama pants that she was wearing when they said goodnight.

His sister, older than him by a year and two weeks, is motionless.

Cristopher steps through the family room, heading toward his parents’ room. Standing now in front of his father, he realizes Arturo’s face and head are obscured with blood.

“What happened?” Cristopher asks. “Do you need anything?”

Arturo stares at Cristopher but doesn’t say a word. He can’t physically speak, but it doesn’t matter. He doesn’t have an answer for his son. The same question is plaguing his jumbled thoughts.

Somewhere among the emotions flooding his being — horror, shock, confusion, sadness — a thought occurs to Arturo, a one-time law student in his native Puebla, Mexico. He shouldn’t touch anything. This is a crime scene.

He obeys his natural instinct, with one exception: He closes the eyelids of his dead wife and daughter.

Cristopher returns to his room and his father, wobbly and disoriented, staggers behind him, grabbing at the walls for support along the way. Together, they join Alejandro, who is in bed.

Blood is dripping down Arturo’s face from somewhere on his head. Woozy, he drifts asleep. Next to him, Alejandro is asleep, too. Cristopher is left to himself, wondering in silence what has happened. He notices two holes in his father's head.

The 9-year-old is traumatized and isn’t sure what to do.

Arturo startles awake hours later, about to vomit. He throws up several times as he tries to make his way to the hall bathroom.

When Cristopher checks on him, Arturo motions him to come closer. He gives him a hug in lieu of the words trapped in his mind. He toys with his iPhone, but nothing happens. Maybe it’s not charged. Or maybe it’s his fingers that aren’t working.

That’s why Arturo hasn’t called for help. And because the family doesn’t have a landline phone and Cristopher’s and Karla’s Galaxy S2 cellphones aren’t charged, nobody has called 911. They suffer alone, in stunned, frozen anguish.

Cristopher’s attention turns to his little brother, a preschooler. He leads Alejandro into his own bedroom and tells him to stay put. He lets Alejandro finish leftover Easter chocolate while he sips water. They flip through books to pass time.

Alejandro decides he wants some juice; before Cristopher can stop him, the youngster slips out of the bedroom and sees his mother, sprawled on the floor.

“Mom?”

“It’s OK,” Cristopher says, as he guides his brother back to his bedroom.

By now it’s 8 p.m. Sunday and Cristopher realizes a way to fetch help: He’ll go to school Monday morning and tell someone. He wakes up at 6 a.m. Monday, as he normally does, steers clear of the bathroom because of the blood and washes his face using a bottle of water from his bedroom. He changes into fresh clothes, packs his book bag and walks over to his father, who is sitting on a living room couch, listless.

Cristopher climbs into his father’s lap and they embrace without speaking.

Now it’s time for Cristopher to get help. He gives Alejandro, who normally would take a bus to preschool, strict instructions to stay put at home, with their father.

Alejandro agrees and reminds his brother to say goodbye to their puppy named KO, an ode to the family’s boxing gym.

“Bye, KO,” Cristopher says.

•••

It’s 8 a.m. on a sunny, tranquil spring day and Mabel Hoggard Elementary School is alive. Cars pour through the parking lot, the playground is filling and soccer games are in full swing.

In this same neighborhood, Metro Police Sgt. Bobby Johnson’s patrol officers are 90 minutes into their workday. They’re keeping an eye out for a man suspected of sexually assaulting a 50-year-old woman early Sunday morning in a vacant, gravel-strewn lot on the southwest corner of Vegas and Tonopah drives.

The suspect description is vague: a slender black male, likely in his 20s, who is about 5-feet-8 or 5-feet-9 inches tall.

Cristopher’s walk to school takes him past a rusted Neighborhood Watch sign. A half-mile from home, he reaches Mabel Hoggard, a place of familiarity and safety.

Cristopher joins a soccer game with friends, but it’s short-lived as the clock strikes 8:30 a.m. — the time to line up by class, recite the Pledge of Allegiance and sing a song or two. During an otherwise-cheerful start to the school day, Cristopher is crying.

His teacher, Miss Wagner, notices. Cristopher, the younger brother of her former student Karla, is not a crier.

“Cristopher, what happened?” Candace Wagner asks.

The words that tumbled out of the fourth-grader’s mouth next would set in motion a discovery so heinous that first-responders would wrestle for months with nightmares:

“My mom and sister are dead.”

•••

The dispatcher doesn’t broadcast the details of the 911 call over the radio system. Instead, she instructs officers to check their in-car computers.

Officer Edward Renfer, a four-year Metro veteran who’s on a traffic stop, reads the details on his screen and immediately responds to the call with lights and siren, arriving within seconds of another officer. Together, they approach the peach-colored, wood-and-stucco house at 1016 Robin St. and peer into a front window.

They see a woman’s body lying on the floor and alert other officers pulling up to the house.

Curtains flap in another window at the south end of the home. They hear a tapping sound, and a small head appears. It’s a child with large, brown eyes and shaggy, black hair framing his face.

Not knowing who might be lurking inside, the officers try to lure the little boy out of the window, but he appears confused and drops out of sight. Seconds later, the front door opens.

A man covered in blood staggers outside. The child in the window zips out next and huddles behind the man’s legs. They’re standing just outside the open door — and what if the assailant is just inside?

Renfer sprints and scoops up the boy, as other officers converge on the dazed-looking man they later identify as Arturo Martinez-Sanchez. He could be their suspect. They don’t know. Medical help is on the way, but they need this man in custody just in case.

The moment overwhelms Arturo.

Put your hands up!

Put your hands down!

Put your hands up!

Get on the floor!

Put your hands behind your back!

The next thing he knows, he’s wearing handcuffs.

About 60 seconds have elapsed since officers arrived on scene.

Sgt. Johnson leads four Metro officers into the house to locate any victims, dead or alive, as well as potential predators hiding inside.

They fan in different directions, careful not to disturb evidence. An open jug of milk rests on the kitchen counter, a hint of normalcy among the shades of red staining nearly every surface.

Blood is smeared on every wall, pooling in bathtubs, coagulating on couches.

“The totality of this house, with the odd exception of the boys’ rooms, suggested that something very violent had occurred, and it didn’t matter which wall or ceiling or floor — every surface displayed evidence of something nefarious,” Johnson, a 20-year police veteran, would say later.

As the four officers and their sergeant walk in silence, a puppy with crimson-stained paws darts in and out of a doggy door, creating a flapping sound.

“Dog in ... dog out,” an officer announces, with each flap of the door.

It’s an unnecessary narration but a welcome human sound in an otherwise inhumane setting. They find a woman and young girl, each with severe head injuries that Johnson would later describe as “incompatible with life.” In fact, homicide detectives would report that the mother had been struck on her head twice with a blunt object; her daughter, at least three times.

Yady and Karla are dead, just as Cristopher told his teacher.

•••

No more than 10 minutes have passed since police arrived. As the day progresses, more than two dozen paramedics, detectives, coroner investigators, crime-scene analysts and others will converge on the now-cordoned-off section of Robin Street.

Curious neighbors gawk, cars drive extra slowly before making U-turns at the barricade and reporters roam the perimeter of the crime scene for people to interview.

Amid the frenzy, Noreen Charlton, a senior crime scene analyst, makes two new friends: Cristopher and Alejandro. They’re in her care for the time being as she photographs them for evidence purposes.

Hanging out in a giant, white truck — Metro’s mobile crime-scene unit — the three chat about school, where they ate lunch last week, what movies they hope to see. Cristopher explains every book in his backpack and every drop of blood on his clothing.

Alejandro is shy, not quite able to grasp what his older brother understands about this day and these people. His protector, Cristopher, tries his best to fill in the gaps.

And when Animal Control shows up later, it’s Cristopher who voices concern for their other surviving family member, an American bulldog.

Who is taking his dog? Where would KO be held? Would he be fed on time?

Inside the house, crime scene analysts document evidence until midnight. They will spend three full days processing the scene, the longest time investigators have spent at a crime scene in more than two decades.

Officers patrol the residence around the clock, warding off nosy citizens, all of whom want an answer to the same question haunting detectives: Who did this?

For the Martinez-Sanchez family, Monday, April 16, ends like this:

KO paces inside an animal shelter kennel. Cristopher and Alejandro fall asleep at Child Haven, the county’s facility for children in its temporary custody. Arturo lies in a hospital bed at University Medical Center, sedated from emergency surgery to repair a brain laceration. Investigators would later say he suffered that injury, and a second skull indentation, when he was struck by a hammer at least three times.

And Karla’s and Yady’s bodies await autopsies at the county morgue.

Chapter Two: After the horror: Unimaginable Grief, Unimaginable Grace

Arturo Martinez-Sanchez is sitting in a private area of the church, the sacristy behind the altar where he is out of view of the congregation. From here he can hear a choir softly singing as his wife and daughter are wheeled forward.

They are in matching white caskets. The one containing the body of 38-year-old Yadira is distinguished by red roses; the roses on top of 10-year-old Karla’s casket are purple.

It’s May 2012, nearly a month since Yadira and Karla were brutally killed, and even if the shock has worn off, the community still quietly seethes.

The church is filled with family — including Arturo’s two sons, Cristopher and Alejandro — friends and strangers. Reporters wait across the street; Arturo isn’t ready to face them quite yet.

No funeral Mass comes without heartache, but this one stings for the Rev. Julio Alberto Alzate, co-pastor of St. Christopher Catholic Church in North Las Vegas. He ate meals with this young family. He baptized their three children. And he is the godfather of 9-year-old Cristopher, the middle child who walked to school and reported the deaths.

The Rev. Julio Alberto Alzate speaks about Arturo's willingness to forgive. Translation: "He is an example of teaching us how to forget lived events that reside deep down in our heart and teaches us to live in peace."

Now, Alzate finds himself alongside the two caskets, asking a community to find the strength to forgive the evil that shattered this family.

On this Friday morning in May, 22-year-old Bryan Clay is in a Clark County Detention Center jail cell, accused of sexually assaulting a 50-year-old woman in a gravel-strewn lot at Vegas and Tonopah drives, then traveling several blocks and entering the home at 1016 Robin St. Inside, police say he viciously bashed the heads of Arturo, his wife and daughter with a hammer.

Police allege he also sexually assaulted Yadira and Karla. Arturo survived, along with 9-year-old Cristopher and 4-year-old Alejandro, who slept through the attacks and awakened to a house of horrors the following morning.

Funerals, it’s said, help with the healing process. They help bring closure, as if that’s possible.

Alzate speaks in his native Spanish, and his co-pastor, the Rev. Ron Zanoni, adds a few words in English, asking mourners to pray for a path to healing and peace.

“That is our prayer for all of us and all those who suffer the tragic effects of violence,” Zanoni says.

Cristopher helps uncles carry the caskets. They pass a vestibule filled with photos from brighter days and wreaths adorned with messages from loved ones.

Karla is seen grinning sweetly, posing with freshly manicured nails and performing splits on a pool table. Her mother smiles broadly for the camera while holding a drink at a restaurant.

Outside, mourners hold white and lavender balloons. A few slip away, drifting into the sky.

Pallbearers hoist the caskets into two awaiting Cadillac Escalades. From here, they will drive a half-mile south to Woodlawn Cemetery, where mother and daughter will be buried in a single grave.

Until now, this family had seemed blessed, succeeding in ways beyond their humble reach.

•••

Arturo and Yady, her nickname to family and friends, met on a college campus in Puebla, Mexico. It was 1992 and they were law students.

When Yady noticed Arturo, she enlisted the help of a friend to make introductions. Oblivious to Yady’s intentions, Arturo nodded and said, “See you later.”

Arturo’s nonchalant demeanor didn’t deflate Yady’s hopes. They exchanged greetings several days later. After a few more days, they again ran into each other.

It was two weeks before the impatient Yady boldly struck, planting a kiss on Arturo. It spurred Arturo to finally ask her out on a date.

For the next six months, they were inseparable in their spare time but, by college standards, were not considered “a couple.” The uncertainty reduced Yady to tears on her birthday, Feb. 1.

“You should be happy on your birthday,” Arturo told her. “Let’s make this birthday happy.”

He asked her to be his girlfriend.

They remained true to one another, even as Arturo took time off from school to care for his ailing mother in Mexico City. He never did finish school.

Arturo sold shoes door to door, which led to his opening a shoe store in Yady’s hometown of Hidalgo. The store reaped $300 a month, not enough to get ahead financially.

After Yady graduated from college, Arturo decided he could make a real living by moving to the United States.

Unable to secure a visa, he would have to cross the border illegally. To his surprise, Yady said she wanted to go along.

She clued in her parents, and her father had but one question: What is your relationship with this man?

They were getting married, Yady said, and three days later, they did. They wed Nov. 27, 1997, at a simple ceremony in a government building. She wore a navy blue pantsuit with red shoes; he wore khaki slacks and a light blue dress shirt.

The newlyweds tried to cross the border together twice with the help of coyotes — smugglers operating an underground network to sneak people into the United States — but U.S. Border Patrol agents caught them each time and returned them to Mexico.

Arturo decided to go alone and then make arrangements to bring Yady.

He succeeded on his fifth solo try on foot, a 3 1/2-day trek that ended safely in Anaheim, Calif. He didn’t know whether he could trust the coyotes to return with Yady, but several days later, they dropped her off not far from Disneyland.

They scrambled for jobs. Yady found work at a fast-food restaurant. Arturo secured day-labor gigs — moving rocks, cutting grass, mopping, anything to earn a buck.

After four months, they accepted a woman’s offer to drive them to Las Vegas, a city booming with construction and new jobs. Arturo paid her $300 for the ride, an amount he would later realize was heftier than two bus tickets.

But they arrived safely, carrying only a bag or two, and that’s all that mattered.

Using fake Social Security cards they got from forged-document peddlers, they easily snagged minimum-wage jobs, including work at a fast-food joint near Rainbow Boulevard. At another place, Arturo made burritos.

The long hours paid for rent; a yellow, older-model Toyota Corolla; and, eventually, their first home: 1016 Robin St. They bought the fixer-upper home for $93,000 in December 1999.

Arturo landed a stable union job as an electrician to suit his growing family. Within a few years, he worked his way up to foreman, making $22 an hour.

He felt good about his decision to move with his bride to the United States.

In the summer of 2001, Arturo and Yady welcomed their first child, Karla Edith. He chose the name for his daughter, the little girl he would more often call “Karlita” or “princess.”

Two little boys followed — Cristopher, born in the summer of 2002, and Alejandro, five years later.

The couple enrolled their children in after-school activities: sports, music, acting classes. They bought the kids a trampoline for the backyard, took vacations to California and spent weekends at church and with extended family. Expectations for their growing children were simple: Earn A’s and B’s at school.

“That’s my goal and that’s their goal, too,” Arturo says.

As his kids grew, Arturo began working out at a gym operated by former boxing referee Richard Steele. It renewed his passion for the sport. During his teen years, he had fought a dozen amateur boxing matches, winning all but one.

There, amid the sweat and burning muscles, a thought occurred to him: What if he opened his own gym?

Yady encouraged him. So did the kids.

In April 2011, using money they had saved, the couple opened Real KO Boxing Club. They rented a storefront in an aging North Las Vegas plaza painted white with a blue roof.

For two months, they worked nights and weekends to spruce up the interior. They envisioned the gym being a community gathering spot for children and teens living near Cheyenne Avenue and Civic Center Drive.

Yady served as accountant. Arturo ran the business and coached several classes. Karla came up with the gym’s slogan: “We grow champions.”

On opening day, seven people enrolled. As word spread, registration increased, keeping Arturo and his family busy in the evenings. The gym wasn’t their money-maker, but it was a dream realized.

Not all dreams last, though. Two weeks after Alejandro was born, the young family moved to North Las Vegas into a newer, bigger home — a purchase they felt confident about after cobbling together enough money for a down payment. They rented out their Robin Street house.

But the region’s emerging housing crisis took its toll on Arturo and Yady, like it did for countless other Southern Nevada homeowners. When escalating payments grew beyond their means, their home fell into foreclosure.

In December 2011, the family returned to its Robin Street home.

Arturo and Yady considered it an unfortunate setback, not an end to their way of life.

•••

These days, Arturo and his two boys live with his sister, Gaudia Martinez-Sanchez, whose words encouraged him to start fighting as he lay hospitalized at University Medical Center.

“Arturo, you have to come back to us,” she whispered three days after the attacks. “You have two babies that need you.”

But Arturo knew he and his boys could never fall asleep again inside 1016 Robin St. They needed a place to live.

In February 2012, Gaudia’s husband, Ken Seal, had bought a sprawling, ranch-style home along a quiet street to accommodate the couple and his wife’s teenage son, Jesus Vazquez.

They didn’t quite know what to do with the extra space, but the house called to them.

Now the home has purpose.

Several days after the funeral, they all move into the house, complete with a backyard pool.

“You can stay here as long as you want,” Gaudia tells her brother. “Feel comfortable. Feel like home. Enjoy.”

This allows Arturo to focus on his physical recovery. He begins physical and occupational therapy May 15 at the Nevada Community Enrichment Program, a day treatment program tailored to people with brain injuries.

Arturo’s injury is considered traumatic — in other words, the result of a blow to his head rather than an unprovoked medical episode. His injury led to memory loss as well as coordination and speech difficulties.

It’s obvious to everyone who greets him at the treatment program. He falls over if someone bumps into him. He doesn’t know the date, month or year. He recalls loved ones but becomes confused easily.

Weeks pass, then months. Arturo improves enough to pass a driving test, regaining his license. For this 39-year-old man, that’s a milestone worth celebrating. It means more independence.

But impediments remain, which is why Arturo is sighing on a Monday morning in late July. He’s sitting at a table with his speech therapist, Julie Peterson.

He has reviewed a paper listing ways to improve one’s memory, but now his cheat sheet is gone, and Peterson wants him to recite the strategies.

He nails four, no problem: repeating information, writing things down, taking video and using iPhone applications. After a pause, he adds one more to the list: daily routines and rituals.

He’s halfway there, but he’s stumped.

“How do you organize your day? What do you keep that information on?” Peterson asks, guiding him to another answer.

“Calendar!” he says.

The pair slog through the remaining tips, with Peterson issuing prompts so Arturo can connect the dots. Defeat etched on his face, Arturo tries to muster a smile.

“It’s going to improve. It’s going to get better,” she tells him. “I don’t want you to get upset over this. I just want it to be a reality check.”

Erasure marks clutter his papers by the end of the session. Arturo often writes the wrong letter, a key indicator of his motor-programming shortfalls. His brain struggles to connect his thoughts with his actions.

So, by 11 a.m., his brain needs a break. It’s time for more physical therapy.

Cued by his physical therapist, Christine Solan, Arturo folds his arms and stands on one leg. With his right foot lifted, he wobbles back and forth. He balances for 30 seconds, uncrossing his arms only once at the 15-second mark.

His time is consistent with what any uninjured person his age should achieve.

“Close your eyes,” Solan tells him next. “Cross your arms as long as you can on one leg.”

The former amateur boxer can only last three seconds — well below the 23-second threshold most people could meet.

“He probably had excellent balance because that sport requires it,” Solan says. “His balance has already gotten a lot better, so I think his balance will continue to improve.”

Less than a month later, on Aug. 23, Arturo has improved in all areas — so much that it’s his graduation day from the Nevada Community Enrichment Program. Gaudia attends along with Cristopher, Alejandro and Arturo’s sister-in-law, Lupita Olmedo.

In a large room filled with workout equipment and mats on one side and tables on the other, a small crowd has formed. Arturo’s case manager, Jerry Kappeler, stands next to him and rattles off a list of accomplishments: Arturo speaks in more complex sentences and has better balance, improved hand-eye coordination and more strength.

Their initial handshake was wimpy at best.

“Now, he crushes my hand,” Kappeler says.

As the accolades continue from therapists, another client, a man sitting in a wheelchair, lets out a whoop and shouts, “All right!”

Arturo is their role model — their reason to hope that one day, they, too, will graduate. But in the world of brain injuries, recovery doesn’t have a finish line.

When Kappeler asks Arturo to speak about his memory improvements, he pauses for a long time. Cristopher gives him a hug.

“I cannot even remember ...” Arturo trails off, shaking his head and passing that question.

It’s a somber moment in an otherwise triumphant day. Arturo tells his fellow program participants, “God bless you,” and thanks his sister for her relentless support.

As Kappeler hands him his certificate of completion, the room erupts in applause, signaling snack time. Gaudia brought homemade flan.

“I used to be a good guest,” Arturo says. He means host. “But now you can get it yourself.”

•••

What’s the key to human resolve? Is it an inner strength, embedded in the human consciousness from birth? Or pure grit exhibited by those facing adversity?

Scholars and theologians can debate. For Arturo, a former altar server rarely seen without a rosary around his neck, the answer came in early summer: He must forgive.

It’s a commandment and a survival necessity.

Arturo shares his feelings with Alzate, a gentle confidant who listens rather than pontificates. He understands Arturo’s desire to move on with his life. In the grief-stricken man before him, he sees an act from the heart.

“If there’s love, you can easily forgive,” Alzate explains several months later. “It comes from inside.”

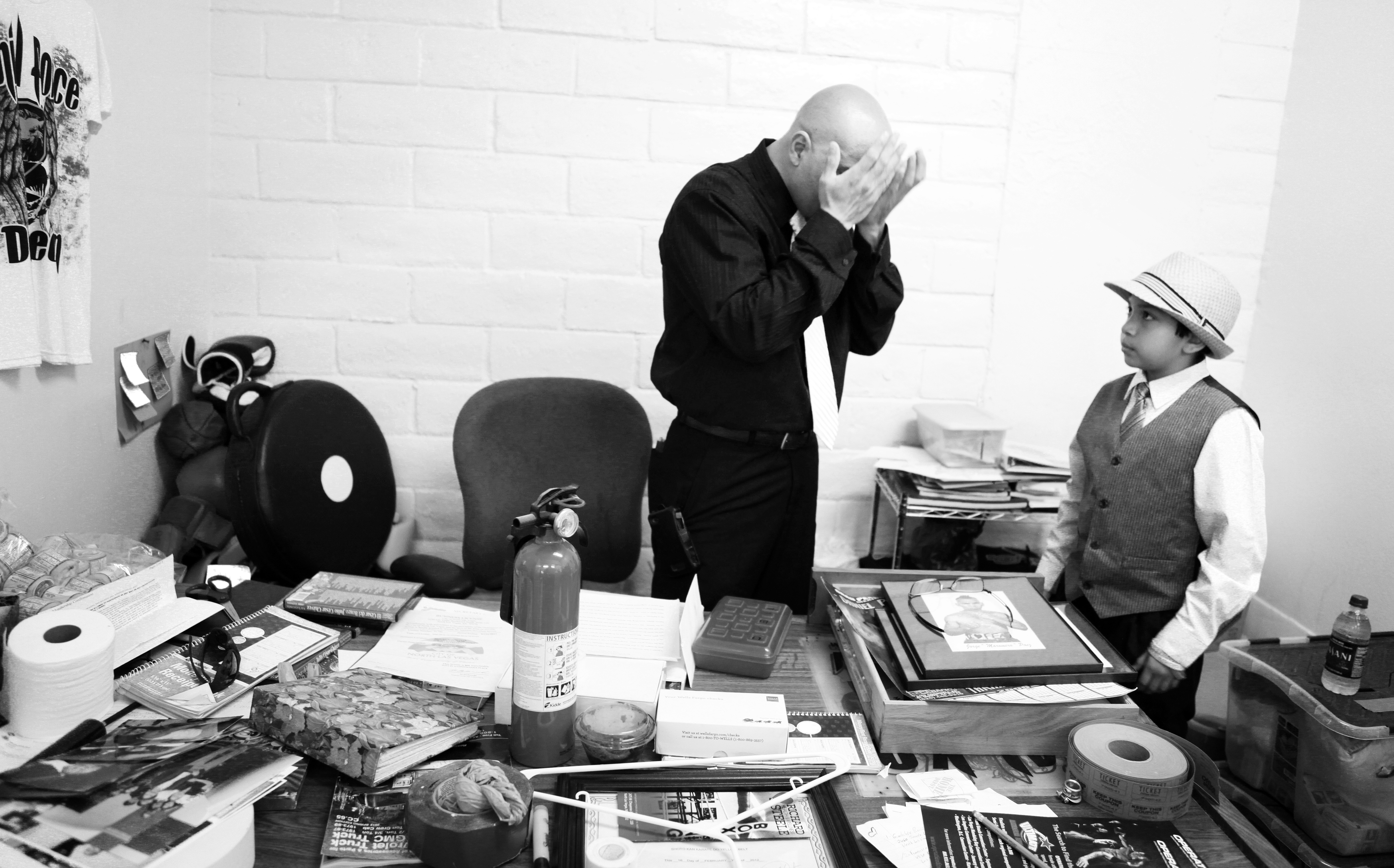

On a hot summer day in early July, Arturo invites the community back to his gym to announce its reopening and offer a personal message. It’s his first appearance in front of reporters since the attacks.

He wears a black collared shirt and black slacks, accented by a white tie. Cristopher and Alejandro don matching grey vests.

As Arturo makes his way to a front table, the boys clutch his sides. And, for the first time, those seated in metal chairs in the gym can see Arturo’s physical wounds: a deep, red scar running from above his left ear to the top of his head and a marble-sized dent on the back of his head.

With Cristopher’s hand on his shoulder and cameras rolling, Arturo looks down at the words he painstakingly wrote during occupational therapy sessions. His voice trembling, he begins:

“I forgive this murderer because of my faith in God and in Jesus Christ.”

With tears streaming down his face, he speaks of his once-happy family, the forgiveness of sins, and his solace knowing he will spend eternity with his wife and daughter in heaven.

And in the process, he delivers a personal manifesto:

“The world is full of evil. This terrible crime is just one of many, many evil things in our world. I choose not to give in to this evil. I choose life and happiness for my sons Cristopher and Alejandro. We choose to turn our heads away from evil and acknowledge the good things in this world. We choose to be strong and move forward.”

Chapter Three: The boys' refuge; the father's hell

It’s the first day of school and Arturo Martinez-Sanchez is anxious. Until today, he hasn’t had to face the morning routine as a single father, and he can’t find something.

He is opening and closing cabinets and peering into the back reaches of drawers. Finally, there it is: the blender lid. Crisis No. 1 averted. He can mix the shake, made of sliced apples, oatmeal, chocolate and two eggs.

Arturo has given himself plenty of time this morning. He awoke an hour earlier, showered and dressed in black slacks, a collared shirt, a belt and dress shoes.

Physically, he’s ready for the day. Emotionally, maybe not so much.

He’ll watch his youngest, 5-year-old Alejandro, start kindergarten and his middle child, Cristopher, 10, enter fifth grade.

Then he will head to the courthouse and face the man who allegedly raped and killed his wife and daughter.

•••

Arturo heads to the bedroom he shares with his two boys in his sister and brother-in-law’s house. It’s time to settle an age-old question on the first day of school.

“Which one do you want?” Arturo asks Alejandro, holding up two T-shirts.

“This,” Alejandro says, smiling sheepishly, pointing to a “Cars” shirt.

Arturo ties Alejandro’s shoes, then inspects his son from head to toe. Alejandro’s black shorts don’t cut it. They’re falling off his skinny frame. Off go his shoes. Arturo rifles through a stack of clothes, snags a tiny pair of blue jeans and hurriedly slides them on Alejandro.

“Ah, perfect,” he says.

So far so good as Arturo warms up to the morning drill. The summer months slid by in a chaotic blur of doctor appointments, physical therapy and small victories amid grief. He regained his driver’s license. He reopened his boxing gym. He publicly forgave Bryan Clay, the suspect. And, slowly but surely, his speech is coming back.

.jpg)

A gold-framed photo of 10-year-old Karla and Yadira, his wife of 14 years, rests on a bedside table. Paper wreaths from their funeral — adorned with messages of love — hang across the room. The decor reminds Arturo and his boys of all they have lost. Karla should be entering middle school and Yady should be making the clothing choices.

In the adjacent bathroom, Arturo glides a comb through Alejandro’s knotted hair as the youngster whimpers in pain.

“Stay strong, OK?” Arturo says.

“And don’t say poopie face to the kids,” Cristopher chimes in, thinking the conversation has turned to school.

It’s almost time to go as the boys head to the kitchen for their shakes. Cristopher gulps his down, eager to be on his way to school and friends; Alejandro protests and only takes small sips when Arturo holds the glass up to his mouth.

“Take it — one, two three,” Arturo says. “Drink it, please.

“More ... more ... more ...”

Arturo’s sister, Gaudia Martinez-Seal, appears in the kitchen. Her son, Jesus, started his first day of high school. Before he left, he hung a Post-it note on the boys’ bedroom door, wishing them good luck.

Gaudia hugs her nephews and traces the sign of the cross over them. With that, Arturo ushers them to the car. As they back out of the driveway, Cristopher turns up the radio for the Neon Trees’ latest pop song.

Summer is over.

•••

"This is your school,” Alejandro tells Cristopher as they pull into a gravel parking lot next to Mabel Hoggard Elementary School.

“It’s your school now, too,” Cristopher says back.

For Cristopher, the elementary school is a place of familiarity, the reason he wanted to return. It was his choice and Arturo approved. Now was not the time for more change.

“Cristopher, how are you, dude?” a staff member calls out as the boys and Arturo make their way to the entrance.

It’s a mob scene outside the school as many parents forgo the drop-off and instead accompany their children into the school’s open-air courtyard.

Alejandro, distracted by the scene and first-day jitters, runs head-first into a pole. Tears well in his eyes.

First stop: the nurse’s office.

“You’ll be fine,” Arturo tells Alejandro as a nurse tends to the emerging red bump above his right eye.

Cristopher takes one look at his brother’s injury and shrieks, “Oh my gosh!”

Arturo again consoles Alejandro, whose tears are drying up as he sits, still wearing his backpack.

“Hate to see your baby go to school?” a nurse inquires.

“Yeah,” Arturo says, then sighs.

“They’ll be fine. We’ll take good care of them,” the nurse says.

Outside again, Cristopher holds his younger brother’s hand as they walk to the playground, where Arturo tells Cristopher goodbye. Cristopher’s teacher will be Miss Maher, a teacher new to the school who, staff members assure Arturo, will be a good fit.

The playground is a scene of frenzied excitement as older children reconnect with friends, see old teachers and meet new ones. In the kindergarten corridor, trepidation might be a better word — for both the students and parents.

As Arturo and Alejandro round the corner, a line of kindergartners is entering Mr. Hernandez’s classroom. Several are crying as parents try to find the right words to boost their spirits.

Genaro Hernandez spots the father-son pair and steps forward.

“Hi, Alejandro! How are you?” he says.

Alejandro smiles but doesn’t speak.

Hernandez guides Alejandro to his seat at a six-student table while Arturo watches from near the door. Today will be about introductions, Hernandez says.

Alejandro turns his head and flashes his dad a thumbs-up sign — Arturo’s cue that, like it or not, it’s time to say goodbye.

“Basically, when they start studying, you’re losing them one cycle at a time,” Arturo says as he makes his way to the cafeteria for a parent meeting. “Kindergarten. Junior high. You start losing them.”

In the cafeteria, filled with other parents of kindergartners, Arturo spots a piano against a wall. He says Karla used to take lessons on it. He stares off into the distance as he recalls the accomplishments of his daughter — his “princess,” his “Karlita,” as he used to call her:

“She was a pianist.”

“She was a yellow belt.”

“She was first place in freestyle swimming.”

The president of the school’s Parent Teacher Student Association opens the meeting by touting the benefits of enrollment at Mabel Hoggard, a magnet school and home of the Challengers.

Principal Celese Rayford offers a small dose of reassurance to any parents struggling with the kindergarten milestone.

“We are a community,” she says. “Please know that as you are dropping your kids off, we are going to take excellent care of them.”

Arturo knows that. Karla and Cristopher grew up attending Mabel Hoggard, and it’s the place Cristopher sought help on that Monday morning in April four months ago.

School is the one certainty in the family’s life as it enters a new reality. What worries Arturo is providing for and raising two sons without their mother and sister.

Arturo contemplates it all as he walks back to his car.

“A lot of stuff goes through my mind,” he says. “I don’t know how I am going to handle the kids for the rest of their lives.”

And then it’s like he hears his own words to Alejandro about staying strong.

“I can deal with this,” he says to no one in particular.

Now it’s time to see the man indicted in the rape and murder of his wife and daughter.

•••

Arturo paces the 14th floor of the Regional Justice Center in downtown Las Vegas. He is joined by family and friends.

They huddle in the hallway as sunlight streams through large windows, reminisce about old times and whisper with a victim advocate appointed by the court.

Arturo is mostly quiet, methodically rubbing a small metal cross that he then slips into the chest pocket of his suit.

The chatter dies as they enter the courtroom, filling two rows of public seating. Sitting just 15 feet in front of them, next to his court-appointed defense attorney, is Bryan Clay, the accused.

Arturo removes the cross from his pocket and grasps it as he eyes the 22-year-old man with short dreadlocks, an unshaven face and standard blue jail attire.

District Court Judge Jessie Walsh enters, breaking the moment and signaling the start of the hearing.

“Your honor,” begins Clay’s defense attorney, Anthony Sgro. “Essentially, Mr. Clay seeks to attack, I believe, four of the counts currently alleged in the indictment. One of them is the burglary charge and the others are the sexual assault charges.”

In June, a grand jury returned a six-page indictment charging Clay with 10 counts connected to his alleged crime spree that began a few blocks away from the Martinez-Sanchez house.

The first three charges — first-degree kidnapping, sexual assault and robbery — relate to the 50-year-old woman Clay allegedly followed, grabbed and forced into a vacant lot at the corner of Vegas and Tonopah drives.

The defense isn’t fighting the legal foundation of those charges.

But there is a fundamental legal issue involving the alleged rapes of Karla and Yady: Were they alive or dead when they were sexually assaulted?

During grand jury testimony, neither the sexual-assault nurse examiner nor the medical examiner pegged whether the sexual assaults occurred before or after each died.

“Rape requires a live victim,” Sgro tells the judge, citing a 1996 Nevada Supreme Court decision. “If there is evidence of an assault and it is impossible to determine pre- or post-mortem, you don’t just charge the most serious crime,” he says.

Arturo and family shake their heads in silence.

Prosecutor Robert Daskas hands the judge a photograph from the crime scene. It’s graphic, he says, and no one else should have to see it.

“What’s significant is the evidence in the case clearly indicates both the mother and the 10-year-old daughter were attacked with a hammer — first the mother in her bed and then the daughter in her bed,” Daskas says. “They were both dragged to the floors of their respective bedrooms, where they were raped by the defendant.”

The blunt, step-by-step description of her niece's and sister-in-law’s deaths pains Gaudia. She buries her head in her hands.

Daskas continues: “Common sense tells us their hearts were still beating for that amount of blood to be present on the floor, where each of them was raped.”

After more back-and-forth between the attorneys, Walsh rules against the defense. All counts remain.

Arturo exits the courtroom visibly drained and numb, with the small, metal cross still within his grasp.

“I have no words,” he says.

Chapter Four: A life in danger, months after an intruder's attack

The boys will not be attending school this September morning. Instead, they will accompany their dad to the hospital, where Arturo Martinez-Sanchez will undergo his third surgery in five months, after being struck hard on the head by what police say was a hammer.

The first two were brain surgeries and involved the repair of a brain laceration toward the front of his head. This one, a cranioplasty, will fix a skull indentation on the back of his head, made by the intruder who raped and killed his wife and 10-year-old daughter in April.

And this is how Arturo has prepared for it — by creating a 21-page last will and testament. It’s sitting on the counter as Alejandro and Cristopher eat breakfast.

“If I was lost, I need my sons taken care of,” the 39-year-old single father says of the document.

The night before, his sister, Gaudia Martinez-Sanchez, made flan, his favorite dessert. He snacked on the custard treat, along with chips, fruit and cereal before fasting for the surgery.

Arturo and his boys temporarily live with Gaudia, her husband and her teenage son; Arturo is her older brother and the reason she moved to the United States.

She tries to give him his space. She lets him come to her. Last night, however, she broke her usual silence and gently prodded Arturo about his feelings.

“You know, what else can I be nervous for?” Arturo told her.

•••

The three-letter question might be impossible to answer: Why?

Why did the suspect pick that modest, one-story home on Robin Street? Why did he attack Arturo; his wife, Yady; and daughter Karla; but not harm the couple’s two youngest children, Cristopher and Alejandro? Why did this happen to them?

The questions run through Arturo’s head on a daily basis. All Arturo knows is he awoke mid-morning Sunday, April 15, and found a horror story within his home. Then he felt something wet trickling down his face. Blood.

Arturo drifted in and out of consciousness for the following 24 hours. On Monday morning, police arrived at the home after Cristopher walked to Mabel Hoggard Elementary School and told school officials a chilling statement: His mother and sister were dead.

Detectives combing the crime scene two days later found a hammer at the bottom of a hole in a cinder-block wall lining the north side of the Martinez-Sanchez family’s backyard. The hammer, with a wooden handle and silver head, was stained with blood.

The discovery supported what doctors suspected: A blunt-force object had been the perpetrator’s weapon.

When Arturo arrived at University Medical Center, he was aphasic. He couldn’t speak.

“It was an odd first encounter,” said Dr. Logan Douds, an endovascular neurosurgeon who was the on-call doctor that day. “We couldn’t ask him any questions to sort of find out how he was doing.”

Dr. Logan Douds, an endovascular neurosurgeon, speaks about Arturo's injuries when he first arrived in the emergency room after the hammer attack.

The injuries on his head spoke for themselves. Douds observed two depressed skull fractures — one on the top, or frontal region of his head, and another on the back side, or occipital region.

The blows to the skull caused a cerebral hemorrhage, which acts like a stroke, in the frontal region, resulting in speech impairments. The injury demanded immediate attention, landing Arturo in the operating room that afternoon for his first brain surgery.

“Some patients make a complete recovery in terms of function,” Douds said, explaining potential outcomes after suffering trauma-related strokes. “Some people don’t have any functional deficits at all. Some people have a permanent deficit.”

Douds and his medical team lifted the skull fracture in the frontal region, washed out the affected underlying tissue and repaired the laceration. A couple of weeks later, Douds operated a second time, placing a piece of mesh over the skull defect.

.jpg) Douds didn’t consider Arturo’s head injuries life-threatening when they met, but no surgery is without risks, especially ones involving the skull and brain. Arturo had cleared his first two major medical hurdles.

Douds didn’t consider Arturo’s head injuries life-threatening when they met, but no surgery is without risks, especially ones involving the skull and brain. Arturo had cleared his first two major medical hurdles.

A marble-sized dent, however, remained on the back of his head — the result of what doctors call a “complex, comminuted fracture.”

Translation: This part of the skull was so pulverized, the bone fractured in multiple pieces and detached from the rest of the skull.

Headaches plagued Arturo throughout the summer. By this time, swelling had subsided, making it clear a deformity existed. But there was a catch: The deformed skull fragment was overlying a vein as large as its name — the superior sagittal sinus. Freeing the skull fragment could pose bleeding risks.

“I made sure he really wanted to have the surgery done for that reason — knowing there’s risks involved,” Douds said.

Arturo decided the potential good outcome was worth the risk. Days later, he called his attorney, Barbara Buckley, director of the Legal Aid Center of Southern Nevada, and asked for help drafting a will.

•••

Despite his sister’s pleas, Arturo insists on driving himself to Valley Hospital for the surgery. The boys pile into his red Ford Escape, which bears the marking of a proud parent: a decal on the back window depicting five stick figures, one for each family member.

Gaudia follows in her own car but, before leaving, posts one last call for prayers on her Facebook account.

“On the way to the hospital. ... God with us and us with his grace.”

It’s the second such message she has posted on the social-networking site. Her first message the previous night announced Arturo’s surgery and elicited an outpouring of support from friends and family in Las Vegas and beyond — another small reminder of strength in numbers.

Alejandro grabs his father’s hand as the family wends its way through the off-white hospital hallways. The pre-surgery waiting room is quiet when they arrive.

Gaudia envelops her brother in a long embrace before they sit down. The waiting begins, interrupted every so often by the arrival of more relatives.

Eventually, the double doors next to the room open and a nurse summons Arturo for pre-surgery preparations. About 15 minutes later, nurses give family the all-clear to enter room No. 20 in the pre-op area.

Arturo is lying in a bed dressed in a hospital gown, with a heated blanket over his body and an IV in his arm.

This is not the man his sons are accustomed to seeing — the one clad in athletic gear and Puma sneakers, or jeans and cowboy boots.

“Alejandro, come on over,” Arturo says.

He makes the sign of the cross over his youngest child’s face as Alejandro begrudgingly relinquishes his hand-held video game.

A nurse enters the room to outfit Arturo with special socks to prevent blood clots, but first she must squeeze her way past the eight family members and friends filling the tight room. Two more people arrive a short time later, including Danny Daniels, a family friend and senior pastor at First Southern Baptist Church south of downtown, who leads the group in prayer.

“We pray you be with Arturo,” Daniels begins.

“We pray to you, God, give the doctors strength and wisdom.”

“Amen,” the group murmurs.

It’s 2:15 p.m.

“I’m too hungry,” Arturo says. “I need In-N-Out.”

As if on cue, Douds arrives and explains the cranioplasty. He reiterates the surgery’s biggest risk: removing the deformed skull fragment.

Afterward, family and friends step into the hallway, leaving Arturo alone with his two sons. He whispers to them as they huddle next to his bed.

“You have to understand,” he says. “You have to keep going until you become big men and do what you need to do.”

He caps the short, man-to-little-man speech with high-fives for each boy. Cristopher, the older of the two, responds by burying his head in his dad’s arms. Alejandro just smiles.

Soon after, Manny Elumba, the operating room nurse, enters and rattles off a checklist of questions:

“How are you doing today?”

“Are you allergic to any medicine?”

“Did you have anything to eat or drink today?”

His last question, which is really more of a statement, is directed at Gaudia, who is standing in a corner of the room, fear etched on her face.

“We’ll take good care of Mr. Martinez, all right?”

“Thank you,” she says.

Elumba clips the IV bag to Arturo’s hospital bed. The bed frames go up.

Arturo gives his sons another hug. This time, Cristopher and Alejandro trace their hands from his head to his chest and side to side, creating two invisible crosses over their surviving parent.

Then Elumba wheels Arturo out of his room and turns the corner, bound for operating room No. 1.

•••

Blue cloth obscures the identity of the patient lying facedown on the operating table, covered almost entirely. The problem spot — in this case, the back of a skull — peeks through an opening.

But before the first cut or even the first touch, Elumba reads aloud patient facts as other members of the six-person medical team listen intently.

Patient: Arturo Martinez-Sanchez

Birthdate: Dec. 11, 1972

Procedure: Cranioplasty

Allergies: None

The brain trust surrounding Arturo — a neurosurgeon, an anesthesiologist, a physician assistant, two scrub techs and an operating-room nurse — agrees in unison.

“Time out at fifteen forty-nine,” Elumba says. It’s 3:49 p.m.

Douds injects a local anesthetic around the indentation on the back of Arturo’s head. Next, he slices the scalp and attaches green clamps to the skin tissue, following the path he made seconds earlier.

Blood seeps out. Just as quickly, however, the physician assistant clears the incision line with a suction tube.

The pair work in unison. Slice, clamp, suction. Slice, clamp, suction.

The incision complete, Douds peels back the 3-inch-by-3-inch flap of skin covering Arturo’s skull and repositions the overhead light for closer examination.

“Please make sure the blood is actually available,” Bruce Burnett, the anesthesiologist, reminds the scrub techs. “Thank you.”

The polite statement underscores the vulnerability of the operation. At any point, something could go wrong, so the team must prepare for the unexpected, such as a blood transfusion.

Douds clutches instruments in both hands and alternates back and forth, clearing soft tissue from the fractured bone below. Meanwhile, a scrub tech gracefully follows the surgeon’s moves and anticipates what he needs next. The rhythm continues until Douds — his white plastic gloves stained with blood — steps toward a notebook computer displaying scanned images of Arturo’s skull and brain.

Returning to the operating table, Douds drills small holes around the deformity and removes the fractured skull in several pieces.

The removal does not disrupt the large, underlying vein. The team can take a deep breath. Now it’s all about cosmetics — turning those fragments into a more normal-looking skull.

“It’s not like repairing car parts,” Burnett says as he watches Douds examine the fractured bone. “Everyone is different.”

In this case, the solution lies in simply flipping the fractured segments. Like a puzzle, Douds pieces the inverted fragments together on a sterile instrument table across the room.

Several snowflake-shaped metal plates, two-hole straight plates and 36 tiny screws ultimately hold the refurbished skull fragments together.

.jpg)

Douds gently places the now-whole fragment back in the gaping hole in Arturo’s skull and glides a drill with a burr over the bone, smoothing any rough edges.

The more-normal bone shape should take pressure off the covering of the brain, reducing the number of headaches. And the dent on the back of his head should be largely nonexistent, aside from some scarring.

At 4:49 p.m., exactly one hour since Elumba called “time out,” Douds folds the skin flap back over the opening. He grabs thread and starts tying.

•••

The familiar face pauses at the hospital room doorway and does a double take.

Arturo, the man who could barely speak when he entered the Nevada Community Enrichment Program several months ago, is sitting on a hospital bed, chatting with his sister.

The two lock eyes and, for a moment, stare at each other in a mixture of surprise and delight. Dawn Zito, an admissions coordinator at the rehabilitation center, was the first person Arturo met when he enrolled in the physical- and occupational-therapy program in early summer.

He graduated from the program Aug. 23.

“How’s it going?” Zito says, smiling broadly as she steps into the room.

“It’s going,” Arturo says, bowing his head to show her the new scars from his surgery two days ago.

The two reminisce about the day they first met. He could only give yes or no answers. Anything more was stunted by his brain injury.

“You’ve come a long way since then,” she says.

Arturo nods in agreement, yet lingering impediments frustrate him. He still mixes up words or can’t find the right word altogether. And his memory falters more often than not. He can remember his childhood but forgets the things a doctor told him an hour ago.

“It’s more getting it out of you,” Zito says. “You have the memories. You just can’t get it out.”

“That’s the problem,” he says, sighing and wrinkling his face.

It doesn’t take long for his frustrations to become evident. Zito bids him goodbye and says it was nice to see him.

“Nice to meet you, too,” Arturo says. He squishes his face, mustering a chuckle. “I mean see you.”

His family shares his worries about a physical recovery: Will he regain lost vision in his right eye? Will his speech ever flow in uninterrupted sentences again? And will the frequent throbbing in his head gradually subside?

Arturo voices these worries most often. His family, on the other hand, fears for his emotional well-being, perhaps to a greater extent.

Arturo’s stubborn and fiercely independent spirit never missed a beat. He made that clear during his initial hospitalization: As their father, Cristopher and Alejandro would live with him, he told his lawyer. End of discussion.

But would the fun-loving and hard-working man who enjoyed motorcycles, boxing and impromptu dances with his wife ever return? A certain spark was missing.

Until this morning.

That’s when Gaudia says she saw a sign of hope — courtesy of a Kit Kat bar tempting her from across the hospital room. There were three on a table. She wanted just one.

Her brother immediately denied her request, then glanced up at her with a mischievous look in his eye. She lunged for the candy bar. He grabbed it first and taunted her.

Finally, he gave her the Kit Kat. And laughed.

And, for a moment, Gaudia wondered if maybe, just maybe, her older brother was coming back.

“I’m guessing he got in this mood because he knows everything went well with the surgery,” she says while Arturo takes a shower in preparation for his hospital discharge. “He was so worried. It’s like one more step.”

Chapter FIVE: The comfort of friends; the compassion of strangers

The technicians at his eye appointment tell Arturo Martinez-Sanchez to be sure to use lubricating eye drops — artificial tears, as they’re called — if his eyes feel dry.

That’s not a problem, he says.

“I could cry any time,” he says.

Arturo’s left iris and pupil are gone, the result of a childhood accident — a shard of glass from a soda bottle damaged his retina, leaving behind a milky gray circle and no vision.

But it can still cry.

Now vision from his right eye is compromised, too, after an intruder broke into his family’s home, raping and killing his wife and daughter and severely injuring him. The couple’s two youngest children, Cristopher and Alejandro, slept through the attack.

The head injuries inflicted upon him stole vision in the bottom left quadrant of his right eye. It’s not a life-altering setback. His central vision, the most crucial spot, was untouched, but for a man without sight in one eye, it represents another frustration on top of monumental grief.

“OK, you see those four lights? In the center, there will be a blinking light,” says Tess Reyes, a diagnostic technician at Westfield Eye Center in Las Vegas, who is testing his peripheral vision. “Press the button every time you see the blinking light.”

Arturo leans forward and peers through a glass lens into the machine. As if playing a video game, his finger jabs a button each time the light blinks.

Click. Two seconds pass. Click. Five seconds pass. Click.

Each time Arturo, 39, misses a blinking light, the machine notes the location with a dark mark, thereby creating a map showing where he has lost vision.

A half-hour later, he meets with his ophthalmologist, Dr. Kenneth Houchin, who compares the test results with those from July.

“It appears to be just about the same, although there could be some lightening in this area that might be encouraging,” Houchin says, pointing to a dark blob in the troubled lower left quadrant close to his nose. “We’ll know within a year. Whatever is still lost in a year’s time after the injury will likely be permanent.”

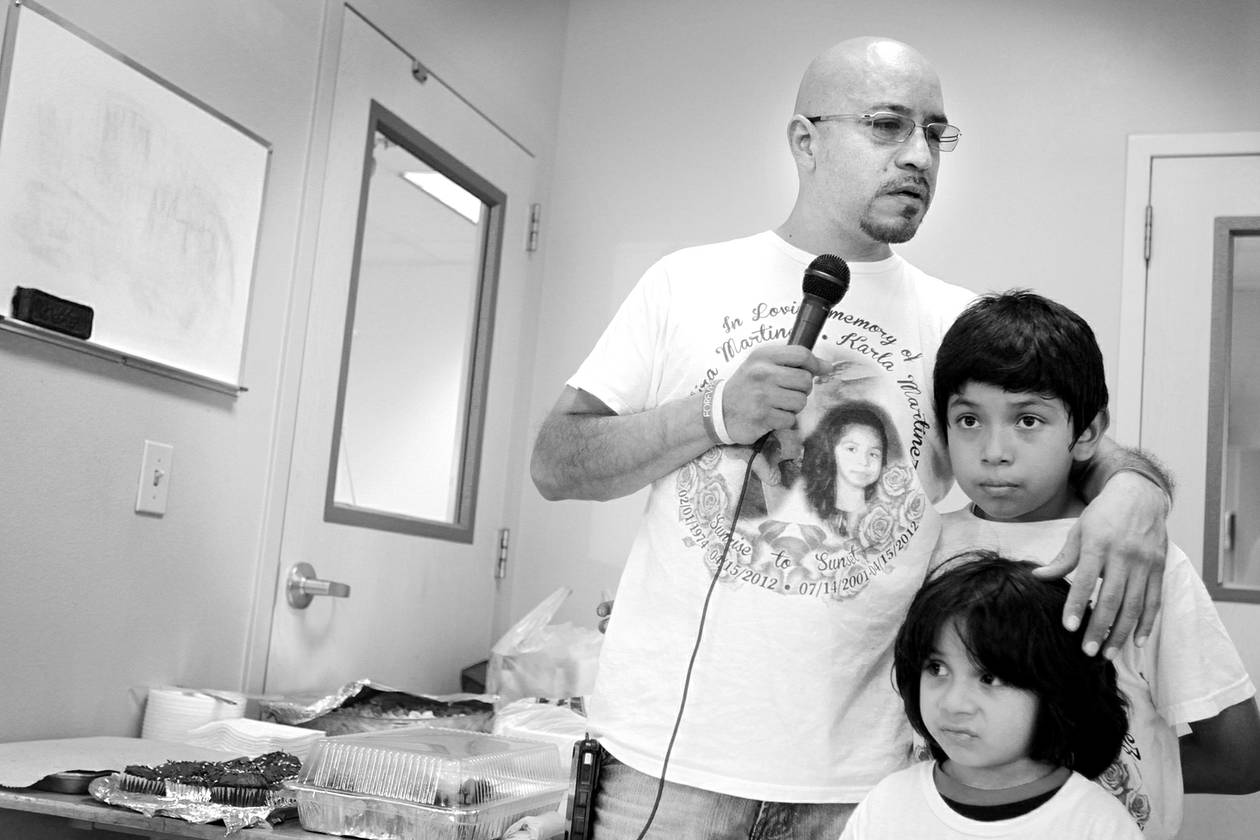

Today is Oct. 15 — six months since Arturo lost much more than his vision. He’s wearing a white T-shirt with images of his wife and daughter that says, “In Loving Memory of Yadira Martinez & Karla Martinez.”

•••

Arturo keeps his days as structured as possible. He drops off Cristopher, 10, and Alejandro, 5, at school, then heads to the boxing gym he reopened in July. Paperwork and maintenance await him. He pumps up-tempo music from his iPhone over the speakers. Occasionally, his coaches stop by, sometimes with their children, for a workout before activity picks up toward evening.

He regularly checks his phone calendar, careful not to miss appointments with his lawyer, doctors, family or the state program that helps crime victims cover medical bills. It could easily feel overwhelming for a newly single father with a brain injury.

“Every day I have something to do,” he says. “Every single day.”

At 3:15 p.m., for instance, he picks up his boys from school and brings them to the gym.

And it becomes apparent to Arturo that, for all the people helping him piece back together his life, he can use his gym — his passion — to help others. This is a place where he feels needed versus needy. It gives him purpose.

Arturo is telling a 19-year-old who aspires to become a professional boxer how to balance on two straddled hand weights.

“Your feet have to be parallel,” he says, motioning with his hands.

Then Arturo turns his attention to a 23-year-old who just started coming to the gym. Arturo flashes him a thumbs-up when the young man punches cleanly and quickly into the air. Quick instructions follow: an elbow adjustment here, a stance tweak there.

Arturo makes teaching look natural, wending his way through the gym — past hanging punching bags, over mats, around the boxing ring — dishing constructive criticism and bits of praise where necessary. He’s in his element. It’s therapy.

But it’s not the only therapy he needs.

That’s why he regularly escapes the gym for a couple of hours and, with Cristopher and Alejandro, attends counseling sessions.

Arturo knows therapy won’t erase Cristopher’s memory of what he saw. But he does what he can. He lavishes the boys with more kisses, a sentiment he learned from his wife, but affection alone is not enough. Words hold power, and sometimes simply talking through feelings soothes pain.

Arturo says his kids need counseling more than he does, but then he pauses to ponder the question: Is counseling helping?

“It’s good for me,” Arturo says. “That’s why I’m doing it.”

With his therapist, Arturo discusses the past, present and future. The boys sometimes draw pictures to express their emotions. The underlying theme, Arturo says, is about moving forward.

If he and the boys discuss what happened to their family, it’s often within the confines of his red Ford Escape — after they leave counseling and drive back to the boxing gym. That’s their quiet time for reflection.

•••

Arturo invested money and sweat into the home at 1016 Robin St., updating the bathrooms and kitchen and painting bedrooms for his young family. But it wasn’t where he wanted to raise his family. Built in 1957, with a pollen-ridden fruitless mulberry out front, the home is not far from a rough neighborhood.

So in July 2007, the couple bought a new, much larger home in a North Las Vegas neighborhood with freshly poured sidewalks, young trees, parks and landscaped streets. Two weeks after Alejandro was born, they moved in.

Arturo and Yady bought their kids a trampoline for the backyard. They bonded with neighbors, enjoying cookouts and holidays together. It was their dream home.

But, like tens of thousands of other Las Vegans, the family found themselves saddled with a house they could no longer afford. Like many of their neighbors-turned-friends, they lost their home.

The family returned to its Robin Street house, which Arturo had been renting out, in December 2011, four months before it would become a crime scene.

Arturo has no plans to ever live there again. For now, he is living with his sister and her family.

In October, he shows the Robin Street house to two commercial real estate agents whom he had recently met.

“Just come on in,” Arturo says, turning toward the front door.

The phrase rolls off his tongue with ease, like a seasoned homeowner welcoming guests.

Plywood covers four front windows; piles of leaves surround two abandoned garbage cans on the side of the house. Arturo carefully undoes two locks bolting the front door and steps inside, joined by Brendan Keating and Sean Margulis.

The two were moved by his story splashed across newscasts immediately after the killings: Devout Catholic man, severely wounded in a hammer attack, forgives man suspected of killing his wife and daughter.

The two men, Bishop Gorman High School graduates, gave him a few hundred dollars to pay a bill and, more important, a standing offer of help in any way going forward.

The men’s generosity is not unique. The savageness of the attacks triggered an outpouring of support, eliciting prayers worldwide and surprise deliveries in the mail.

A winemaker in Washington state sent Arturo bottles of wine and a note: “I read your tragic and heartbreaking story. I can’t imagine your pain. However, as a Christian myself, I was awed by your capacity for forgiveness. Your story to me is a true example of walking in the word. Please accept some of my wine as a fellow Christian.”

An elderly woman living in Las Vegas began sending $100 checks addressed to the “Arturo Martinez Family,” with “donation” written in the bottom left corner. A retired man now living in Las Vegas called homicide detectives and asked how he could give workout equipment to Arturo’s gym. Others have donated time and labor.

Later, a wealthy Henderson couple would establish funds for Cristopher and Alejandro that they can access after they graduate high school, perhaps to pay for college.

And then there’s Barbara Buckley, director of the Legal Aid Center of Southern Nevada, who took Arturo as a pro-bono client after receiving a call from the Mexican consulate. She has been helping him sort out legal matters in the aftermath of the tragedy, such as applying for a U Visa, which extends temporary legal status for immigrant victims of crime. Buckley agreed with Arturo that he should consult with someone in the real estate business to figure out what to do with the house.

That leads to today and the tour of the house he’s giving these two real estate agents. He wants advice about what to do with it. He carries a flashlight and points out blue splotches covering the walls. It’s the color left behind by chemicals used to remove bloodstains.

“There was blood right here,” Arturo says, pointing to a wall in the master bedroom near where his wife died. “There were two or three palms — her palms.”

This is Arturo’s fourth time visiting the house since the killings. It’s eerie, devoid of almost any sunlight. But Arturo has most markings memorized, such as this one: the faint outline of a cross within a blue stain. He theorizes it’s the handiwork of the cleaning crew who entered after investigators left the home.

The tour seems almost mechanical, and maybe it’s a defense mechanism.

“Every time I come to this place and I see this,” he says, pausing, “I don’t know. It’s just crazy.”

In the backyard, Arturo shows them a balance beam he bought his daughter. He yearns now for a new home for him and his boys.

“I’m having my first baby — a girl — in 20 days,” Keating tells Arturo. “Walking through the house evokes a lot of emotions, so I want to do anything that I can to help you.”

The comment about pending fatherhood lights up Arturo, who rattles off what any new parent should expect: lots of crying the first few months, followed by toddlers trying to grab everything in reach. He smiles broadly while reminiscing.

“It’s something that is incredible,” he says. “Every time my kids were born, it was amazing.”

As the trio heads back to the front yard, Arturo spots Cristopher and Alejandro skateboarding on a neighbor’s driveway. A car is approaching north on Robin Street.

“Watch the car! Watch the car!” he yells.

•••

The time-honored tradition comes each Oct. 31 as opposing forces unite, darting up and down streets on a common mission. Goblins run with princesses. Witches confer with superheroes.

And, under darkened skies, the line between good and evil appears blurred. On Halloween, children embody heroes or villains and face their fears — the spider in the bush or the boogeyman surely lurking around the corner — on a quest for candy.

For most kids, fear is based on the unknown. It’s irrational.

But Cristopher and Alejandro know horror.

Alejandro dons a Spider-Man costume. His older brother, who will attend middle school next year, wears his regular clothes.

“Oh my gosh, all these lights,” Cristopher laments, as parents snap photo after photo.

The group calls itself the Junction Peak family, an ode to the North Las Vegas street they lived on before foreclosures splintered their tight-knit community. Last year, Arturo and Yady dressed as pirates as the families went trick-or-treating.

As this Halloween approached, Arturo’s former neighbor, Heather Zmak, sent him a text message: “I know tomorrow is going to be hard for you, but all I can think about is every year we went trick-or-treating together.”

That’s all it took. Tonight, four families, including Arturo and his boys, meet at the northwest valley house of his other former neighbors, Fred and Tessa Haas. The kids fan out to different homes as the adults follow.

Zmak and Fred Haas lag behind for a minute as they watch their friend Arturo interact with his boys. They are assessing him.

“He looks good, huh?” Zmak asks.

“Yeah, he sounds good, too,” Fred Haas says.

Arturo releases a deep, from-the-belly laugh as he watches Cristopher and Alejandro scramble between homes, then check their loot after each stop.

“Candy, candy, candy,” the young Spider-Man murmurs as he crosses a street.

The scene is festive. Orange lights adorn homes. Giant, inflatable pumpkins fill yards, along with light-up skulls and fake spiders.

Meanwhile, a man dressed as Michael Myers, the terror-inciting character in the “Halloween” movies, walks ominously around the neighborhood, silently staring from behind a white mask.

His shtick works. Zmak’s 6-year-old daughter, Joleigh Courtney, jumps and wraps her arms around Arturo.

“Don’t worry about it,” he says. “You’re safe.”

Up the street, there’s a garage converted to a haunted house. The kids run toward it, but Alejandro backs off, frightened.

Arturo scoops Spider-Man into his arms and carries him through the dark space offset by strobe lights — all the while assuring him there’s nothing to fear. It’s just a few pretend zombies. Alejandro whimpers the entire time, softening only when they exit.

“See, I told you,” Cristopher says. “It’s not scary.”

As the group reconvenes outside, the Michael Myers imposter tries again. He makes a beeline toward them, but it’s of no use. The children and parents feign blood-curdling screams and laugh.

Chapter Six: Prayers for yesterday, hope for tomorrow

Tantalizing smells of an impending feast waft through the apartment as giggling chaos reigns in a back bedroom. Welcome to the kid zone.

Five-year-old Alejandro Martinez and a cousin wrestle on the carpet, inching precariously close to a television perched on a stand. In the back corner, a door to a walk-in closet opens and shuts, the hinges rattling each time. Youngsters scramble in and out, playing a game no one knows but them. Alejandro’s older brother, 10-year-old Cristopher, checks in frequently, making sure he’s not missing out.

Fourteen-year-old Ana Olmedo, the oldest in the room, surveys it from her spot on an oversized bean bag in the middle of the room. She smiles at the ruckus, a cheery scene that masks underlying sadness.

It’s Thanksgiving Day, a bittersweet gathering for this extended family because of the loss of Yadira Martinez, 38, and her daughter, Karla, who would have been 11. They were slain 7 months earlier.

Arturo Martinez-Sanchez is without his wife and daughter; his two boys are without their mother and sister.

“Karla, she was very understanding,” Ana says of her cousin. “She was kind. She always cared about others before herself. She was honest. She never let you down.”

Yadira, known as Yady to family and friends, was her favorite aunt, a patient listener but also the first person to crank up the music at family gatherings and start dancing.

Yady would have loved that her side of the family is hosting this holiday gathering. Old stories evoke refreshing laughter.

There was the time Ana rolled Karla’s hair in curlers made from paper bags, the time they tumbled so hard on a slip-and-slide that it broke, and the time they slipped through a narrow crevice during a family hike.

Yady’s brother, Lupe Olmedo, walks in to check on his children, briefly interrupting the storytelling session.

“That’s the thing,” he says. “We have good memories in all of this.”

A giggling 8-year-old’s wisdom sets the tone for the day.

“You know what else is going to be a memory?” the girl asks. “Today.”

•••

Before Arturo packed his two boys in the car and headed to his brother-in-law’s home for the day, he posted a quick message on his Facebook page.

He asked God to bless family and friends — including his fellow union members — who helped him reopen his boxing gym. It’s his place of familiarity, his refuge.

Today, he’s sitting on his brother-in-law’s sofa, holding a newborn nephew.

“I forgot how to cradle little babies,” Arturo says as he snaps his fingers above the baby’s head to grab his attention. “But now I kind of remember.”

A mound of food is growing on portable tables in the middle of the living room. The early arrivals from the kitchen: smoked turkey with Mexican-style stuffing, bread with a chipotle and mayonnaise dipping sauce, and cochinita pibil — pork marinated in too many spices to name.

By 7:30 p.m., the table is complete and the kids emerge from the back bedroom. They jockey for seats near one another as their parents, aunts and uncles join them, forming a circle around the table. There are 21 adults and children in the home this evening. Pictures of Karla and Yady hang on the wall.

Everyone links hands and bows their heads, asking God to watch over the souls of Karla and Yady.

With his sons on either side of him, Arturo continues the prayer, pausing every few seconds to find the right words. In Spanish, he prays for all who cannot be with their families on this day and, perhaps speaking from inner pain, asks for them to be well por los siglos de los siglos — forever and ever.

With the prayer of petition complete, and as little ones squirm in metal chairs, now comes the prayer of thanksgiving:

For allowing us to be united on this night even though two important people are missing.

For my husband’s job, for the health of all of us.

For all the blessings like a roof over our heads, our food, our clothing.

For giving me a sister and a niece who are so special."

Napkins wipe away tears. Wives comfort husbands. Arturo embraces his boys. And, after the final family member finishes speaking, they recite the Lord’s Prayer.

At its conclusion, a clap echoes, followed by more. The applause crescendoes, and everyone is smiling.

•••

At his chiropractor’s office, Arturo lies on his back atop a leather therapy bed that is rumbling with the sounds of massaging rollers. With his eyes closed, his chest rising and falling, he is the picture of tranquility.

It’s early December and Arturo has been coming here several times each week for more than a month, focusing on a single goal: being able to jump rope again. For that to happen, he needs to be mostly free of back pain and numbness in his fingertips, left hand and leg.

After 20 minutes, he moves to a back room and flops down on a bed-like contraption that will stretch his spine and help mend a compressed nerve.

Chiropractor Nancy Fallon adjusts the table’s settings and straps two belts around Arturo that are attached to pulleys. Most patients think the gentle tugging feels good and either fall asleep or chat on the phone, she says.

As the treatment begins, Arturo pulls out his iPhone and checks his voicemail. The message is from a debt collector, jolting Arturo out of his relaxation.

He calls back while still strapped to the table.

“You guys are making me stressed,” he tells the lady on the other end of the line. “I don’t owe you any money. They already talked to me last week.”

Arturo explains a state-funded program that helps victims of crime is covering the bill in question. The debt collector wants more details, such as the date of the police report.

“The day was April 16, 2012,” he says.

The call is over and Arturo tries again to relax.

•••

With little fanfare, Arturo bids goodbye to his 30s, surrounded by family and friends in his boxing gym. He turned 40 in December.

A friend gives him a gold rosary, now dangling from his neck. It joins the small crucifix he carries in his wallet.

He relies on his faith to cope with the unnatural, gruesome deaths of his wife and daughter. This week, television monitors remind him that he is not alone.

Some 2,500 miles away in a postcard-perfect place called Newtown, Conn., dozens of families have joined Arturo’s nightmare after a gunman entered an elementary school and mercilessly killed 20 first-graders and six staff members. Cruel is the word Arturo uses to describe the massacre.

Arturo knows something about what the families of the Newtown victims will discover: Full healing seems a Herculean task, but time will help. Hours elapse into days and weeks into months. Progress comes with setbacks, but life does not stop, hence the onslaught of Christmas decorations covering walls and shelves everywhere he goes.

On Dec. 14, Arturo changes his relationship status on Facebook from “married to Yadira Martinez” to “single.” There’s a reason: Arturo is taking one of those proverbial steps forward. A month earlier, Arturo had asked an old family friend, Gisela Corral, to dinner. He enjoyed her company, she enjoyed his, so they continue seeing each other.

Arturo understands others might question his decision to start dating eight months after he lost his wife. He says only he knows when the time feels right.

Several weeks into their courtship, Arturo shares the news with perhaps his toughest critics: Cristopher and Alejandro.

“What are you going to do if I’m single all your life?” Arturo asks them.

Cristopher, who is more vocal about missing his mother than his younger brother, ponders the question in silence but doesn’t object.

The conversation with his boys wasn’t entirely spontaneous. These are the difficult subjects many couples broach during marriage, perhaps after a near-miss on the highway or a particularly frightening story on the evening news: What would happen if one of us dies unexpectedly? Would the children be OK? What about finances? And should the surviving spouse seek love again?

Arturo and Yady didn’t dwell on these grim questions, but Yady made clear one request: “If you find someone that fits you, the first thing you have to think about is the children.”

Arturo believes his sons deserve a father who is happy — not the man prone to tears they have observed since April. A good relationship breeds happiness.

•••

The poor Christmas tree sitting in a northwest valley home doesn’t know it has an enemy, but across town, Arturo is plotting its ouster.