The Crisis of Identity: Covering Immigrants and Refugees

Eleven million undocumented immigrants live in the U.S., not only without the same basic rights as citizens, but with the constant fear of losing their freedom and livelihood. Sixty-three percent have been in the country at least 10 years. How do journalists report on immigrants and grapple with a system one speaker described as "a modern form of apartheid"? Click here for full video coverage, and tips from workshop speakers.

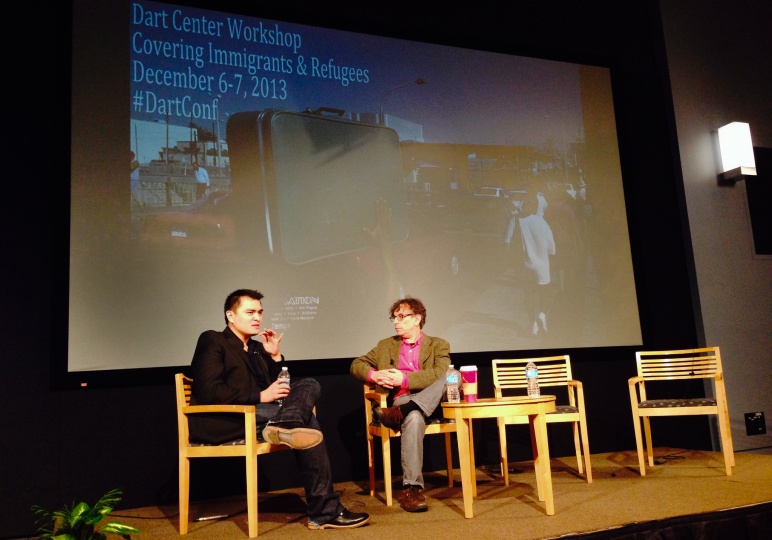

The Dart Center’s “Covering Immigrants and Refugees” workshop at the WHYY studios in Philadelphia spanned two jam-packed days at a time that Executive Director Bruce Shapiro described as a “highly politically charged moment” in the debate on immigration policy. Sponsored by the Scattergood Foundation for Behavioral Health, the workshop featured 11 talks from accomplished journalists and experts in the field, discussions on policy, law and social responsibility and the practical challenges of covering a sensitive and complex issue with wide-ranging consequences.

By the end of 2013, an estimated two million people will have been deported during President Obama’s administration, more than a thousand a day, a faster pace than ever in U.S. history. Eleven million undocumented immigrants live in the U.S., not only without the same basic rights as citizens, but with the constant fear of losing their freedom and livelihood. Sixty-three percent have lived in the U.S. for at least 10 years. Kica Matos, Director of Immigrant Rights and Racial Justice at the Center for Community Change in Washington DC and one of the workshop’s featured speakers, called the American system “a modern form of apartheid.”

The workshop began Friday with a keynote presentation by Andres Pumariega, Professor and Chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Cooper University Hospital and Health System and Cooper School of Medicine at Rowan University, who has devoted his career to working in the areas of children’s systems of care and cultural diversity in mental health. Pumariega presented a picture of immigrants, and their children, with mental health needs that are virtually untended to. Aside from the challenges immigrants face in trying to acclimate to a new environment—loss of extended family support, loss of familiar values and language, economic stressors—the vast majority of immigrants have left their native country under traumatic circumstances. The impact of this trauma is difficult to measure and may even be passed on to the next generation with significant consequences. Pumariega cited studies showing that children of immigrants are the third-highest group at risk for schizophrenia, with an incidence rate 4.5 times higher than the average. Immigrants themselves are the fifth-highest risk group for the disorder. Perhaps not surprisingly, studies showed that immigrants who were less acculturated were healthier.

Fifty-eight percent of America’s undocumented immigrants are from Mexico. Joanna Dreby, an assistant professor of sociology at SUNY Albany and the author of a book on the children of Mexican migrants, spent time with children of undocumented Mexicans in Ohio and New Jersey. Their fear of deportation was so ingrained by their parents that they knew automatically to “sit straight” if they ever saw a police car; Dreby noted one incident in which a man was deported as a result of a traffic infraction. In her interviews with 110 of these children, 81 of them said they were proud of their Mexican heritage, but only 27 said they were proud of their immigrant heritage. In the so-called “nation of immigrants,” the word “immigrant” has become associated with shame.

The psychological impact of living with no official identity can take many forms. For Jose Antonio Vargas, a U.S.-based journalist and documentary filmmaker who revealed himself to be an undocumented immigrant in a 2011 New York Times Magazine story, the desire to see his byline was what sold him on journalism. “My name on a piece of paper,” he marveled. “For someone who’s undocumented, who doesn’t have papers, that was like, hey, I exist.” Vargas lied about having a driver’s license in order to get his first journalism job, and had to take buses and taxis to crime scenes in order to cover them; twice he had to hitchhike. He went on to become part of the Pulitzer Prize-winning team at the Washington Post for its coverage of the Virginia Tech massacre. At 32, he is still trying to figure out how he can become a U.S. citizen. He has lived in the U.S. since arriving from Philippines at the age of 12.

Immigration reform and the question of how to handle undocumented people living in the U.S. are issues ensnared in Congress, with the Republican Speaker of the House John Boehner seemingly resolved to keep it that way, at least for now. Regardless of the outcome of the languishing proposal put forward by the Democrat-led Senate earlier in the year, Peter Gonzales, President of the Welcoming Center for New Pennsylvanians and an immigration attorney by training, told the audience that further debate on the direction of the policy is crucial. “If current proposals move forward, we’re moving away from a family-based system to a merit-based system. There needs to be a real debate about the value change that brings to our country.”

Compared to the rest of the world, the U.S. continues to let in more immigrants than any other country, but the numbers of immigrants to the U.S. has significantly declined, pointed out Edward Schumacher-Matos, NPR’s ombudsman and the James Madison Visiting Professor on First Amendment Issues at Columbia Journalism School. “The great migration wave is essentially over,” Schumacher-Matos said. “It topped out four to five years ago. The number of people coming in compared to leaving has been more or less flat.” He cited the poor economy and law enforcement as the primary factors.

What has also changed, mostly to the benefit of minority groups, is the media, including the advent of social media, which has revolutionized advocacy. But for immigrants, that comes with a catch. Technology has increased the danger that their secrets could come to light, and talking to journalists only magnifies the risk. Denise Ziya Berte, a clinical psychologist and the director of mental health for the Latin American Community Center, implored the journalists in the room to consider it an ethical obligation to learn the background of their subjects and make sure those subjects understand the consequences of speaking on the record. “Make sure you don’t disclose something that will get them deported by accident,” she said.

Erika Almiron, Executive Director of Juntos, a Latino immigrant-led community organization working for human rights, trains the immigrants she works with to talk about how they want to tell their story. “I’ve seen community members get spun by media and they are devastated,” she said. A panel of veteran immigration reporters from the Los Angeles Times, Boston Globe and the Philadelphia Inquirer, agreed that journalists have an obligation to explain the consequences subjects might face by talking to them. Michael Matza, of the Inquirer, said journalists should think of the obligation akin to the Miranda Warning.

Cindy Carcamo, an immigration reporter for the Los Angeles Times, spends significant time with her subjects before interviewing them. She asks them, “Is this a story they want to read, do they want to think about it first?” Shapiro, who moderated the day’s events, added, “We have to remember the vast power deferential between us and the people we’re reporting on.”

Terminology alone is a thorny issue for journalists and posed unresolved questions. Carcamo said several years ago she stopped using the term “illegal immigrant,” instead opting for “undocumented immigrant.” The Inquirer's Matza agreed, though he noted that even “undocumented” was technically inaccurate. “They do have documents,” he said. “They’re just not legitimate documents so… there’s always going to be some caveat.”

Fernando Chang-Muy, a lecturer in law at University of Pennsylvania, outlined the legal system refugees and asylum seekers face. In order to meet the legal standard to be granted status, he explained, they must prove both that they are “afraid” and that they are facing individual persecution based on one of the following factors: race, religion, nationality, social group, or political opinion. In order to make their case, immigrants often submit journalistic work as supporting materials.

That the work of journalists is used in court by immigrants and refugees has become a more complicated and intriguing proposition in light of the transformation journalism continues to undergo, one in which a new openness exists in thinking about how to approach stories that could previously have been considered outside the strict boundaries of objectivity. During the workshop, the intersection of journalism and activism was discussed from both sides. Jose Arreola, the outreach and organizing manager at Educators for Fair Consideration in Oakland, CA, aids low-income immigrant students in their pursuit of a U.S. college education. In his experience, journalists who identify as allies of the immigration reform movement have a better chance of getting closer to the communities and people. “I don’t know what kind of lines that crosses journalistically,” he said, “but those are the best journalists we’ve worked with in the past.”

From the journalistic side, Gary Pierre Pierre, the Executive Director of City University Graduate School of Journalism's Center for Community and Ethnic Media who also founded and publishes the Haitian Times noted that with community news in particular, “part of what you have to do is highlight some of the positive things that are happening.” The angriest call he ever got over a story, he said, was because of a headline that called Haiti the poorest country in the west. “The woman said, ‘I expect to see that in the New York Times but not in the Haitian Times,’ and I had to agree with her.”

Still, the classic shoe leather approach works for Maria Sacchetti, the Boston Globe’s immigration reporter, who works her beat by going to the courts, the cafes where immigrants hang out, and even approaching them on the street. “Give people your card and cell phone number and ask them questions,” she said. “I always say, have you ever heard of someone’s children being taken away, etc? If so, call me anytime day or night…. Now I’m getting calls from jail.”

Sacchetti said she files FOIA requests all the time. “Make sure you really tailor them,” she said. She said to explicitly state: “I want to examine the government’s actions in these cases.” “If there is a question of the government’s integrity, you should mention that as well,” she added.

All participants stressed that the lack of services for immigrants makes the role of journalism particularly crucial. Erika Almiron, Executive Director of Juntos, pointed to an underreported high school dropout crisis among undocumented immigrants who are led to believe, incorrectly, that they can’t go to college.

Alia Malek, an author and journalist, who spent time in Syria during the revolution, pointed out that immigration problems usually begin with a failure to stop oppression and violence. “We can’t keep letting places disintegrate and think we can do these big population movements,” she said.

Full video coverage of the event will be available here on the Dart Center website soon. The conference was also documented in real time on Twitter at #dartconf.