Moral Injury

This provocative three-part series examines the concept of moral injury, a phenomenon where combat or operational experiences transgress deeply held moral and ethical beliefs that undergird a service member’s humanity; often seen as damage to the soul. Judges praised the series for “gracefully and confidently marrying the humanity and understanding of its survivors with a gritty, powerful investigation that breaks new ground.” Originally published in the Huffington Post in March 2014.

PART ONE: THE GRUNTS - DAMNED IF THEY KILL, DAMNED IF THEY DON'T

How do we begin to accept that Nick Rudolph, a thoughtful, sandy-haired Californian, was sent to war as a 22-year-old Marine and in a desperate gun battle outside Marjah, Afghanistan, found himself killing an Afghan boy? That when Nick came home, strangers thanked him for his service and politicians lauded him as a hero?

Can we imagine ourselves back on that awful day in the summer of 2010, in the hot firefight that went on for nine hours? Men frenzied with exhaustion and reckless exuberance, eyes and throats burning from dust and smoke, in a battle that erupted after Taliban insurgents castrated a young boy in the village, knowing his family would summon nearby Marines for help and the Marines would come, walking right into a deadly ambush.

Here’s Nick, pausing in a lull. He spots somebody darting around the corner of an adobe wall, firing assault rifle shots at him and his Marines. Nick raises his M-4 carbine. He sees the shooter is a child, maybe 13. With only a split second to decide, he squeezes the trigger and ends the boy’s life.

The body hits the ground. Now what?

“We just collected up that weapon and kept moving,” Nick explained. “Going from compound to compound, trying to find [the insurgents]. Eventually they hopped in a car and drove off into the desert.”

There is a long silence after Nick finishes the story. He’s lived with it for more than three years and the telling still catches in his throat. Eventually, he sighs. “He was just a kid. But I’m sorry, I’m trying not to get shot and I don’t want any of my brothers getting hurt, so when you are put in that kind of situation ... it’s shitty that you have to, like ... shoot him.

“You know it’s wrong. But ... you have no choice.”

Almost 2 million men and women who served in Iraq or Afghanistan are flooding homeward, profoundly affected by war. Their experiences have been vivid. Dazzling in the ups, terrifying and depressing in the downs. The burning devotion of the small-unit brotherhood, the adrenaline rush of danger, the nagging fear and loneliness, the pride of service. The thrill of raw power, the brutal ecstasy of life on the edge. “It was,” said Nick, “the worst, best experience of my life.”

But the boy’s death haunts him, mired in the swamp of moral confusion and contradiction so familiar to returning veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

It is what experts are coming to identify as a moral injury: the pain that results from damage to a person’s moral foundation. In contrast to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, which springs from fear, moral injury is a violation of what each of us considers right or wrong. The diagnosis of PTSD has been defined and officially endorsed since 1980 by the mental health community, and those suffering from it have earned broad public sympathy and understanding. Moral injury is not officially recognized by the Defense Department. But it is moral injury not PTSD, that is increasingly acknowledged as the signature wound of this generation of veterans: a bruise on the soul, akin to grief or sorrow, with lasting impact on the individuals and on their families.

Moral injury raises uncomfortable questions about what happens in war, the dark experiences that many veterans have always been reluctant to talk about. Are the young Americans who volunteer for military service prepared for the ethical ambiguity that lies ahead? Can they be hardened against moral injury? Should they be?

With widespread public impatience to move beyond the long war years, it’s easy to overlook the pain that endures among service members and their families. Experiences like those of Nick Rudolph and tens of thousands of others are theirs to bear. Many have found peace and acceptance: I did what I had to do, and I did it well and honorably. Others struggle to reconcile the people they have become with those innocent selves who jubilantly enlisted just a few years before. Either way, they manage mostly out of sight and on their own.

Yet a glimpse into their world also raises troubling questions for those of us outside the military – about wartime morality, about the accountability of those who encouraged or tolerated the decisions to go to war. What is the culpability of those who engineered the wars? Of those who approved the funding that enabled the fighting to go on, year after year? What of those who demanded the end of the draft in 1973 and its replacement with a professional fighting force? This “all- volunteer” military excused almost all Americans from service, while its relatively small numbers mean those who do serve must deploy again and again, and again.

.png)

As the broad moral injury of these wars is acknowledged, what is our part in the healing?

“Maybe people don’t want to talk about or know about what can happen to some of our sons and even some of our daughters when they go defend the country. It’s not politically correct. It’s not attractive,” said Michael Castellana, a psychotherapist who provides moral injury therapy at the U.S. Naval Medical Center in San Diego. “But it’s the truth.”

‘Bad Things Happen In War’

Until now, the most common wound of war was thought to be PTSD, an involuntary reaction to a remembered life-threatening fear. In combat, the physical response to fear and danger – hyper-alertness, the flush of adrenaline that energizes muscles – is necessary for survival. Back home, it can be triggered suddenly by crowds, noise, an argument – causing anxiety, anger, sleeplessness and depression. PTSD can be quickly diagnosed, and therapy at last is more widely available.

It is not fear but exposure that causes moral injury – an experience or set of experiences that can provoke mild or intense grief, shame and guilt. The symptoms are similar to PTSD: depression and anxiety, difficulty paying attention, an unwillingness to trust anyone except fellow combat veterans. But the morally injured feel sorrow and regret, too. Theirs are impact wounds caused by the collision of the ethical beliefs they carried to war and the ugly realities of conflict.

.jpg)

Most people enter military service “with the fundamental sense that they are good people and that they are doing this for good purposes, on the side of freedom and country and God,” said Dr. Wayne Jonas, a military physician for 24 years and president and CEO of the Samueli Institute, a non-profit health research organization. “But things happen in war that are irreconcilable with the idea of goodness and benevolence, creating real cognitive dissonance – ‘I’m a good person and yet I’ve done bad things.’” Most veterans with moral injury, he said, “self-treat or don’t treat it at all.”

A moral injury, researchers and psychologists are finding, can be as simple and profound as losing a loved comrade. Returning combat medics sometimes bear the guilt of failing to save someone badly wounded; veterans tell of the sense of betrayal when a buddy is hurt because of a poor decision made by those in charge.

The scenarios are endless: surviving a roadside blast that strikes your squad, but losing lives for which you felt responsible. Watching as your dead friends are loaded onto helos in body bags. Being wounded and medevaced yourself, then feeling burdened with guilt for leaving behind those you had sworn to protect. Seeing evil done and being unable, or unwilling, to intervene.

.jpg)

“An individual on a mission may at the end have questions about the morality of what went on, and most guys reconcile that fairly rapidly,” said Thomas S. Jones, a retired combat-decorated Marine major general. He is fiercely fond of young Marines and runs a retreat for the wounded, Semper Fi Odyssey, where he sees many cases of moral injury. He speaks with a parade-ground staccato, occasionally punctuating his thoughts with a concussive “Hell-fire!”

The majority of moral injury cases go much deeper, he said. “They’re more about survivor’s guilt, death of children, death of civilians, that are just part and parcel of combat action. We continue to see guys four, five years on, still struggling.

“This is experience talking! Hell-fire!”

Dr. James Bender, a former Army psychologist who spent a year in combat in Iraq with a cavalry brigade, saw many cases of moral injury among soldiers. Some, he said, “felt they didn’t perform the way they should. Bullets start flying and they duck and hide rather than returning fire – that happens a lot more than anyone cares to admit.” Bender found himself treating anxiety and depression among soldiers “doubting the mission, doubting the fundamental nature of who they are – pretty deep stuff.”

‘We Did It All For Nothing’

Moral injury is as old as war itself. Betrayal, grief, shame and rage are the themes that propel Greek epics like Homer’s Iliad, and all have afflicted warriors down through the centuries.

But during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, it proved especially hard to maintain a sense of moral balance. These wars lacked the moral clarity of World War II, with its goal of unconditional surrender. Some troops chafed at being sent not to achieve military victory, but for nation- building (“As Iraqis stand up, we will stand down”). The enemy, meanwhile, fought to kill, mostly with the wars’ most feared and deadly weapon, the improvised explosive device. American troops trying to help Iraqis and Afghans were being killed and maimed, usually with nowhere to return fire. When the enemy did appear, it it was hard to sort out combatant from civilian, or child.

At home, as the rest of America gradually decided to oppose the wars as wrong and unjustified or futile, it became difficult for troops and their families to justify long and repeated deployments.

Navy Cmdr. Steve Dundas, a chaplain, went to Iraq in 2007 bursting with zeal to help fulfill the Bush administration’s goal of creating a modern, democratic U.S. ally. “Seeing the devastation of Iraqi cities and towns, some of it caused by us, some by the insurgents and the civil war that we brought about, hit me to the core,” Dundas said. “I felt lied to by our senior leadership. And I felt those lies cost too many thousands of American lives and far too much destruction.”

Dundas returned home broken, his faith in God and in his country shattered. In addition, he was diagnosed with chronic severe PTSD. Over time, with the help of therapists, friends and what he calls his ”Christmas miracle,” his faith has returned.

As the wars dragged on, it became clear that the campaigns to win hearts and minds were not working, and often not appreciated. For some who fought, the memories of their sacrifices have since become tempered by the recent deterioration of security in Iraq and Afghanistan. “We did it all for nothing,” said Darren Doss, 25, a former Marine who fought in Marjah, Afghanistan, and lost friends in battle.

In both wars, context made it tricky to deal with moral challenges. What is moral in combat can at once be immoral in peacetime society. Shooting a child-warrior, for instance. In combat, eliminating an armed threat carries a high moral value of protecting your men. Back home, killing a child is grotesquely wrong.

Guys like Nick Rudolph ended up torn and confused, feeling unhappy and out of place, perhaps guilty and ashamed, or disturbed by their own numbness. Many newly returned veterans simply shrink from civilian society, unable to craft an answer to a jaunty “Thanks for your service!” or “So how was Afghanistan?”

Or the worst: “Did you kill anyone?”

“I can’t go to a bar and start talking about combat experience with somebody – people look at you like you’re crazy,” said a Navy combat corpsman who served in both Iraq and Afghanistan and asked not to be identified by name. He returned burdened with guilt over the lives he couldn’t save. “People say, ‘Thanks for your service.’ Do you know what I did over there? It just seems like you’re being patronized. Don’t do that to me.”

Afraid or unwilling to be judged by civilians, many new veterans isolate themselves, never speaking of their wartime experiences. Unable to explain, even to a wife or girlfriend, the joy and horror of combat. That yes, I killed a child, or yes, soldiers I was responsible for got killed and it was my fault. Or yes, I saw a person I loved get blown apart. From there it can be an easy slide into self-medication with drugs or alcohol, or overwork. Thoughts of suicide can beckon.

“Definitely a majority” of returning veterans bear some kind of moral injury, said William P. Nash, a retired Navy psychiatrist and a pioneer in stress control and moral injury. He deployed as a battlefield therapist with Marines during the battle of Fallujah in 2004. “People avoid talking about or thinking about it and every time they do, it’s a flashback or nightmare that just damages them even more. It’s going to take a long time to sort that out.”

That’s certainly true for Nick Rudolph. Back home at Camp Lejeune, N.C., in January 2012, after three deployments – a total of 16 months in combat – he was sinking in a downward spiral. Drinking so heavily that he picked up a DUI and got busted a rank, losing his prized position as a squad leader. Seeking help, he snuck off-post to see a civilian therapist. There, he was prescribed sleeping pills and twice slept through morning formation, getting slapped with two unauthorized absences. All this added up to what the Marine Corps considers a “pattern of misconduct.”

At war, he’d been exposed to IED blasts six times and shot once, while he was manning a machine gun in a firefight. He’d risked his life, led men he loved in combat and seen some of them die. And now that he’d come home sick at heart, the Marine Corps, which he also loved, meant to kick him out.

Let’s pick him up now, a year or so later, in Philadelphia. Despite his earlier trouble, he’s been honorably discharged from the Marine Corps and is rooming with Paul Rivera, a Marine buddy from Afghanistan. Nick is working as a bodyguard for a security firm. His physical wounds have healed. Physically he is here. But the sounds and sensations and urgency of battle keep puncturing the peaceful civilian reality he’s trying to occupy.

“Coming back, I didn’t know what could help, like ... how do I get those feelings to stop?” Nick said. He can be out in public and then comes something like a panic attack: He feels the adrenaline rush of combat, the crazy excitement, the hyper-alertness ... and watches again as the boy comes around the wall. “The feeling hits you and like ... I don’t want to be like that.

“I just want to be normal.”

‘Your Trust Has Been Ruined And Broken’

At the U.S. Naval Medical Center in San Diego, close by the sprawling Marine base at Camp Pendleton, staff psychologist Amy Amidon sees a stream of Marines like Nick Rudolph struggling with their combat experiences. “They have seen the darkness within them and within the world, and it weighs heavily upon them,” she said.

Morally devastating experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan have been common. A study conducted early in the Iraq war, for instance, found that two-thirds of deployed Marines had killed an enemy combatant, more than half had handled human remains, and 28 percent felt responsible for the death of an Iraqi civilian.

If the resulting moral injury is largely invisible to outsiders, its effects are more apparent. “I would bet anything,” said Nash, the retired Navy psychiatrist, “that if we had the wherewithal to do this kind of research we’d find that moral injury underlies veteran homelessness, criminal behavior, suicide.”

The moral injury of Sendio Martz involved neither killing a child nor disillusionment with the mission. It was the weight of command responsibility, and the guilt and shame he feels for having been unable to bring all his guys home safe.

Martz is a stocky man, soft-spoken with a gentle manner. Haitian-born, adopted and home-schooled by religious American parents, he’s got a pretty firm grip on moral values and personal responsibility. That made him a good squad leader, responsible for the lives of a dozen or so Marines.

In April 2012, Martz was 26 and a Marine sergeant already on his third combat deployment, in the Kajaki District of southern Afghanistan. He’d lost a good friend in combat, 22-year-old Lance Cpl. William H. Crouse IV, of Woodruff, S.C. Martz’s unit, 1st Battalion 10th Marines, had taken other casualties. Now, Martz was leading his guys out on daily foot patrols through some of the same terrain and most heavily contested places in Afghanistan. IEDs everywhere, hidden in the dry, tall grass and rocky scrubland.

When they’d departed Camp Lejeune a few months earlier, wives and sweethearts and parents had crowded around to say their tearful goodbyes, imploring Martz, Make sure you bring my boy back, now. Looking him in the eye, hand on his shoulder. Keep my boy safe.

“Well, that’s a high order,” Martz told me, “given that I am the one directing these guys where to go and I don’t know where anything is. I can’t say, ‘Oh don’t go there, there’s a bomb there, and there’s a guy over there, make sure you watch him and don’t get shot.’ You are praying that the decision you make is the right one, and if it is the wrong one – which a couple of decisions were the wrong ones – you are paying the price and you are living with it.

“I don’t think I’ve ever been so stressed in my life.”

It was a young Afghan boy, Martz found out later, who detonated 40 pounds of explosives beneath Martz’s squad. He was one of the younger kids who hung around the Marines. Martz had given him books and candy and, even more precious, his fond attention. The boy would tip them off to IEDs and occasionally brought them fresh-baked bread. One day, as Martz’s platoon walked a routine patrol, the boy yanked a trigger wire from a hidden position. Whether he had been a secret enemy all along or whether some incident had turned him against the Americans are questions Martz wrestles with to this day.

But the effects of the blast were immediate. The detonation and blizzard of jagged shrapnel felled Martz, knocking him unconscious, and ripped through his squad. Every Marine went down wounded. Luckily, no one was killed, but several were severely injured.

Martz fought back to consciousness. He checked to see if his legs were there (they were), and got on the radio. “As a leader you can’t – I wasn’t allowed and couldn’t allow myself to crumble, or just give in to despair,” he said, his thoughts and words accelerating as he remembered.

We were talking in a quiet corner of the Wounded Warrior barracks at Camp Lejeune in November, shortly before Martz received his medical separation from the Marine Corps (his traumatic brain injury from the IED blast ended his dream of a lifelong career as a Marine). It took a while for that maelstrom of remembered sound and images to slow and fade – his men lying injured, a dazed Martz directing the evacuation of casualties and getting his surviving guys fighting back.

Martz told me that he looks on that incident as his own failure because he didn’t spot the IED before it went off. Because he didn’t warn his men away. “I’d say one of the things I struggle with the most is, all my guys got hurt and I let them down. It’s a constant movie, replaying that scenario over and over in my head. I constantly question every decision I made out there.”

Almost three years later, he’s “kind of stuck,” he said. He seems to be moving on with his life, taking college courses to become a mental health therapist. But inside, he’s not healed. “I have a hard time feeling comfortable around kids, because it was that kid that we got close to, and to have that same kid turn around and blow you up, it shatters your reality of what’s OK and what’s not OK. Your trust has been ruined and broken. The only ones you trust are the guys you went with.”

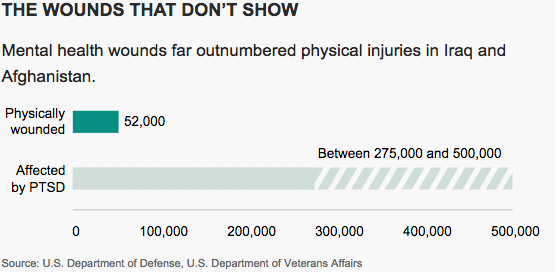

The evidence suggests that such invisible wounds are widespread. A study by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center found that for all the military personnel medically evacuated from Afghanistan between 2001 and 2012, the most frequent diagnosis was not physical battle wounds but “adjustment reaction.” This category includes grief, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress and other forms of moral injury and mental disorders caused or inflamed by war. Between the start of the Afghan war in October 2001 and June 2012, the demand for military mental health services skyrocketed, according to Pentagon data. So did substance abuse within the ranks.

The statistics suggest a massive and widespread wartime trauma whose scope and depth we are only now beginning to grasp. And it worries people like Marsha Four, who was a combat nurse in Vietnam and knows war trauma intimately. She eventually found purpose and solace running a veterans center in Philadelphia, before she retired last year to work with the Vietnam Veterans of America.

Vietnam veterans like Four have their own struggles. But most of them served only one tour. The new veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan, she believes, are especially wounded, because they serve multiple combat tours. “What have we done to this generation?” she wonders. Moral injury, acknowledgement and forgiveness, aren’t so easy. “But we gotta give it a shot. Otherwise, we are going to pay the price for what we have done to them.”

“Civilians are lucky that we still have a sense of naiveté about what the world is like,” said Amy Amidon, the Navy psychologist. “The average American means well, but what they need to know is that these [military] men and women are seeing incredible evil, and coming home with that weighing on them and not knowing how to fit back into society.”

I asked Maj. Gen. Jones, who is deeply concerned about moral injury and its effect on combat Marines, whether he thought war itself is immoral, whether moral injury is unavoidable in war. I wanted to know what he’d meant when he said actions that involve moral transgressions are “part and parcel” of combat. He weighed his answer carefully before responding.

“A democracy is dependent on having guys that will come forward and put their right hand in the air and volunteer and do things that others decide [need] to be done,” he said. “You have to have a military that will do things, regardless.”

Blood Under His Fingernails

Outside of Marjah, Afghanistan, January 2010. On a routine combat patrol, a platoon from 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, enters an adobe compound in a farm village. Walking point, at the head of the column, is Lance Cpl. Zachary Smith, from Hornell, N.Y. He is 19. An IED suddenly erupts beneath him, tearing off both his legs and scything down other Marines with shrapnel wounds. Cpl. Zachary Auclair rushes to save him, frantically pulling out tourniquets and bandages, and he is soon bathed in Smitty’s blood. That’s when the platoon’s sergeant, 28-year-old Daniel M. Angus, steps on a second IED and the blast blows him apart, killing him instantly. In the chaos, Staff Sgt. Warren Repsher, wounded in the face by shrapnel, is on the radio calling for a medevac bird, and Smitty is dying in Auclair’s arms.

A medical evacuation helicopter is seen in the background in this photo taken during Stephen Canty’s time in Afghanistan.

Late that afternoon Darren Doss, a slim, black-haired 22-year-old, watched as his fellow Marines zipped up the two body bags, placed them tenderly on stretchers and ran out to the waiting helicopter. Away it went with the remains of Smitty and Angus, and Doss with a heavy heart turned back into the tent.

“And Auclair is sitting there with, like, guts hanging off his helmet and blood all over his stuff. He is crying and he has baby wipes out trying to clean under his fingernails, but the baby wipes are all dried up,” Doss recalled. “I wanted to talk to him, maybe try to cheer him up, but I didn’t know what to say, so I, like, gave him a pack of baby wipes I’d gotten in the mail, and I just went outside.”

Doss fell silent. He was sitting with his arms on his knees, head down, eyes wide and unseeing. Two of his former platoon-mates, Nick Rudolph and Stephen Canty, sat watching him. They’d gotten together in Philadelphia for a reunion of sorts: Canty was video-taping interviews for a documentary about the struggles of returning combat veterans. The camera was off and for hours they’d just been talking.

Doss picked up the narrative: The battalion held a memorial service for Smitty and Angus. The next day, Doss’s platoon went out on patrol and immediately there was a large explosion and Marines started taking fire. “We were in open desert and you could hear rounds bouncing off the rocks and no one took cover because we were like, just flat open,” Doss said.

Burning with revenge, the Marines responded with a hurricane of rifle and machine-gun fire, blowing apart adobe walls and ripping one insurgent to shreds. “We fucked up this dude, and another guy was like dragging him, dragging him behind a wall,” said Doss. “And I saw him throwing up after he dragged that dude in and we, like, just leveled the place, shot the whole place up, went insane! But ... yeah.”

Then what? Doss paused, glancing around to where Rudolph and Canty were sitting, listening.

“We walked back in and I had an MRE,” a military ration, he said. The room erupted in laughter. Life at war goes on!

That gaiety hides a deeper, lasting pain at losing loved ones in combat. A 2004 study of Vietnam combat veterans by Ilona PIvar, now a psychologist the Department of Veterans Affairs, found that grief over losing a combat buddy was comparable, more than 30 years later, to that of bereaved a spouse whose partner had died in the previous six months.

‘A War Of Moral Injury’

In Afghanistan, some ugly aspects of the local culture and the brutality of the Taliban rubbed American sensibilities raw, setting the stage for deeper moral injury among Marines like Nick Rudolph.

He remembered one time where Marines helped local Afghans build a school, near Combat Outpost San Diego, outside Marjah. “And all the kids went to that school, and the Taliban came over and splashed acid in their faces and, like, horribly deformed them,” he said. “And it was because they went to a school that we built and they didn’t like it. They didn’t view it as we were trying to help them be educated. They just didn’t give two fucks at all.

“You see the Afghan tradition of having basically boys dance for grown men and they give them money and the guy who gives the most money gets to take the boy home. We are partnering with guys who are basically screwing the neighbors’ kids, 6- and 7-year-olds, and we are supposed to grin and bear it because our cultures don’t mesh?” Rudolph said, his voice rising. “When I really want to fuckin’ strangle those dudes?”

Stephen Canty, now 24, is living in Charlottesville, Va., and trying to make sense of his own wartime experience. He told of manning a vehicle checkpoint one day, when along came a middle-aged man on a moped with two bruised little boys on the back. They had makeup on and their mascara was running because they were crying, and the Marines knew they’d been raped. “So you check ‘em,” Canty said of the men and boys, “and they have no weapons, and by our mission here they’re good to go – they’re OK! And we’re supposed to keep going on missions with these guys.

Stephen Canty, now 24, is living in Charlottesville, Va., and trying to make sense of his own wartime experience. He told of manning a vehicle checkpoint one day, when along came a middle-aged man on a moped with two bruised little boys on the back. They had makeup on and their mascara was running because they were crying, and the Marines knew they’d been raped. “So you check ‘em,” Canty said of the men and boys, “and they have no weapons, and by our mission here they’re good to go – they’re OK! And we’re supposed to keep going on missions with these guys.

"Your morals start to degrade.”

On his second combat deployment in Afghanistan, Canty shot and killed an Afghan who was dragged into the Marines’ combat outpost just before he died. “I just lit him up,” he recalled, brushing his long hair out of his eyes. “One of the bullets bounced off his spinal cord and came out his eyeball, and he’s laying there in a wheelbarrow clinging to the last seconds of his life, and he’s looking up at me with one of his eyes and just pulp in the other. And I was like 20 years old at the time. I just stared down at him ... and walked away. And I will ... never feel anything about that. I literally just don’t care whatsoever.”

But Canty wondered what kind of person didn’t have qualms about killing. “Are you some kind of sociopath that you can just look at a dude you shot three or four times and just kind of walk away? I think I even smiled, not in an evil way but just like, what a fucked-up world we live in – you’re a 40-year-old dude and you probably got kids at home and stuff, and you just got smoked by some dumb 20-year-old.

Stephen Canty joins HuffPost Live to discuss some of the more difficult situations he found himself in while serving in the military.

“You learn to kill, and you kill people, and it’s like, I don’t care. I’ve seen people get shot, I’ve seen little kids get shot. You see a kid and his father sitting together and he gets shot and I give a zero fuck.

“And once you’re able to do that, what is morally right anymore? How good is your value system if you train people to kill another human being, the one thing we are taught not to do? When you create an organization based around the one taboo that all societies have?”

Canty is bright and articulate. For a guy who never feels anything about killing, he constantly monitors and analyzes his feelings about war, rubbing together his thoughts about duty and morality like worry beads, until they’re raw.

“My thought was, you did what you had to. But did I really? I saw him running and I lit him up. It’s the right thing to do in war, but in every other circumstance it’s the most wrong thing you could do,” he said. Faced with those kinds of moral challenges, “your values do change real quickly. It becomes a war of moral injury.”

Canty’s moral injury is his own struggle. But his intimate, dark knowledge of war is also a gift – of insight, which he badly wants others to share.

“We keep going regardless of knowing the cost, regardless of knowing what it’s gonna do,” he said. “The question we have to ask the civilian population is, is it worth it, knowing these mental issues we come home with? Is it worth it?”

PART TWO: The Recruits - When Right and Wrong are Hard to Tell Apart

The recruits came at a trot down the Boulevard de France at the storied Marine Corps boot camp at Parris Island, S.C., shouting cadence from their precise parade ranks. Parents gathered on the sidewalks pressed forward, brandishing cameras and flags, yelling the names of the sons and daughters they hadn’t seen in three months.

“He said he lost 25 pounds!” cried a younger brother of Kenneth Karpenko of Corry, Pa. Now, Kenneth and hundreds of other recruits were about to graduate and folks had come from all over the country for Family Day, which opened with this recruit formation run. “There he is!” someone shrieked as a blur of olive drab streamed past. Kenneth’s mom, Pam Karpenko, dabbed tears from her cheeks and managed to say, “We are so proud!”

Is she comfortable with her son becoming a warfighter, with American troops still being killed in Afghanistan and trouble brewing elsewhere in the world? “Oh, we prayed about it and he prayed about it – he knew it was what God wanted,” she said. “We are good with that.”

It’s a proud and painful scene to watch, for it’s clear that there will be more wars, and that there will always be young Americans eager to sign up to fight. In three months, these recruits have earned the right to be called Marines. More training will come later. But there is no way, really, to prepare them for the emotional extremes of war: trauma for some, including moral injury, a violation of the sense of right and wrong that leaves a wound on the soul.

“You just can’t communicate the knowledge of war to somebody else. It’s something that you know or don’t know, and once you know it you can’t un-know it and you have to deal with that knowledge,” explained Stephen Canty, a thoughtful 24-year-old who went through boot camp here in 2007, before his two combat deployments to Afghanistan.

Army basic and Marine boot camp are rigorous preparation, of course. Recruits become lean and hard. They learn to work in teams, to obey orders without hesitation or question, to shout “AYE SIR!” in unison, to fire an assault rifle at human-silhouette targets. They march in close- order drill, navigate overland at night with a compass, demonstrate how to treat a sucking chest wound and fight each other with pugil sticks and boxing gloves. They memorize the Marine core values or the seven Army values.

Stephen Canty with his squad in Afghanistan.

Stephen Canty with his squad in Afghanistan.

But can they be trained to make life-altering decisions in conditions of moral ambiguity, and to live comfortably with their actions? Can anyone really be inoculated against moral injury? Can it be prevented? The experiences of some recent combat veterans, at least, suggest not.

“We have come back, we have had brothers die in our arms, we’ve picked up parts of other people,” 28-year-old Marine Sgt. Sendio Martz told me one day at Camp Lejeune, N.C., last fall, shortly before his medical discharge from the Marine Corps. He spoke haltingly, searching for the words. “And you are completely angry at the situation you were put into ... not angry because you signed up but ... what happened you weren’t fully prepared for.”

The physical and technical training at Parris Island is laced with lessons on morality and values. Drill instructors hammer into recruits a rigid moral code of honor, courage and commitment with the goal, according to the Marine Corps, of producing young Marines “thoroughly indoctrinated in love of Corps and Country ... the epitome of personal character, selflessness, and military virtue.” The code is unyielding. “There is no room in the Marine Corps for either situational ethics or situational morality,” declares a standing order issued in 1996 by the then-commandant, Gen. Charles Krulak.

The Army’s moral codes are similar, demanding loyalty, respect (“Treat others with dignity and respect while expecting others to do the same”), honor and selfless service.

All this may sound like the moral ideals by which most Americans strive to live. But the military’s moral codes are different: They are issued to each recruit along with a weapon and the training, and eventually the authorization, to kill. Success on the battlefield may call for the suspension of basic notions of civilian morality in order to accomplish the mission. Thus the military codes add dimensions of loyalty, duty and personal courage, and back up those values with a requirement of rigid and unquestioning discipline and obedience to lawful orders. The Army’s Soldier’s Creed demands that troops “always place the mission first.”

The entire military is “a moral construct,” said retired VA psychiatrist and author Jonathan Shay. In his ground-breaking 1994 study of combat trauma among Vietnam veterans, "Achilles in Vietnam," he writes: “The moral power of an army is so great that it can motivate men to get up out of a trench and step into enemy machine-gun fire.”

The military’s moral structure is intended to help guide troops through “morally ambiguous situations,” said Marine Col. Daniel J. Haas, who commands the recruit training regiment here.

“We think about this all the time,” he said. In morally tricky situations where you have to make a split-second decision, “ultimately, the answer you come up with is the one you will have to live with. You’ll be more likely to live with your decision if you make it a considered, values-based decision.”

But in war, asking troops to meet the ideals and values they carry into battle – always be honorable, always be courageous, always treat civilians with respect, never harm a non-combatant – may itself cause moral injury when these ideals collide with the reality of combat. Accomplishing the mission may mean placing innocent civilians at risk. Duty, honor and discipline may mean obeying an order you know to be misguided – and later cause a feeling of having been betrayed by your leader.

The great moral power of an army, as Shay puts it, makes its participants more vulnerable to violation, and to a sense of guilt or betrayal when things go wrong. It was his work with Vietnam combat vets, in fact, that led him to recognize that their trauma often came from a deep sense of betrayal. He recognized that the official definition of PTSD failed to describe their mental anguish, leading him to coin the term “moral injury.”

The ideals taught at Parris Island “are the best of what human beings can do,” said William P. Nash, a retired Navy psychiatrist who deployed with Marines to Iraq as a combat therapist. “It’s these values that give you some chance of doing something good in a war, and limiting collateral damage, however right or wrong” the war itself is. The problem, he said, is that “war will break these values.

“There is an inherent contradiction between the warrior code, how these guys define themselves, what they expect of themselves – to be heroes, the selfless servants who fight for the rest of us – and the impossibility in war of ever living up to those ideals. It cannot be done. Not by anybody there,” Nash said. “So how do they forgive themselves, forgive others, for failing to live up to the ideals without abandoning the ideals?”

Warriors come home “and something is damaged, broken. They feel betrayed; they don’t trust in these values and ideals any more.”

As Stephen Canty, the former Marine, put it, “We spent two deployments where you couldn’t trust a single person except the guys next to you.” Back in civilian society now, Canty said, “We have trouble trusting people.”

‘Bad Things Still Happened’

Even when armed with a set of rigid values and discipline, warriors in combat can be caught in situations where they have no opportunity to choose between right and wrong. In the often chaotic fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan, where there was no clear distinction between enemy insurgent and innocent civilian, young Americans could act in good conscience, and in accordance with a strict moral code, and still suffer moral injury.

During a gun battle outside Marjah, Afghanistan, in early spring of 2010, a Marine squad of Charlie Company, 1st Battalion 6th Marines (“Charlie One-Six”), was pinned down in a gully, taking intense fire from an adobe compound. Unable to move forward or to retreat, the squad leader OK’d an attack and Lance Cpl. Joseph Schiano, a 22-year-old on his second combat tour, lifted a rocket launcher to his shoulder, took aim and fired.

The blast blew apart much of the adobe building. As the dust settled, the Marines could hear shouting and wailing. Their interpreter said, “They want to bring out the wounded.” And as the torn and bleeding bodies were dragged out, it became clear that the Taliban had herded women and children into the building as human shields.

“And Schiano is leaning against wall, just sobbing,” recalled Canty, who was Schiano’s squadmate at the time. “The thing is, you couldn’t have known.”

But as Canty himself often says, once you know the truth of war, you can’t un-know it. After that tour in Afghanistan, Schiano left the Marine Corps and went home to Connecticut. The war still weighed heavily on him. He couldn’t fit back. Daytimes, he felt he didn’t belong. At night, he had screaming nightmares.

One Sunday afternoon several weeks after he returned, Schiano went off the road in his 2003 Volkswagen Jetta and rammed a utility pole. At his funeral in Riverside, Conn., Marines of One-Six carried the casket. He was 23 years old.

In other combat situations, where the kind of “considered, values-based decision” that Col. Haas advises is theoretically possible, young troops have two handicaps. Their ability to make split-second moral assessments, a function of the prefrontal cortex of the brain, may not be fully developed, researchers say, a fact that may be familiar to any parent of teenagers. But in war, when 20-year- olds are licensed to kill, the stakes are far higher. And they may not be getting enough sleep, another critical factor in making moral judgments, according to Shay, the VA psychologist. A 2008 Army study reported that combat troops were averaging less than six hours of sleep a night, month after month.

“The problem for a lot of these kids is that psychologically, morally and neurologically they are not fully developed by any stretch of the imagination,” Nash said. That makes it impossible “for the people pulling the triggers, impossible for the medics and corpsmen and doctors who are treating people ... you want to try to live up to the ideal of protecting people, and you fail to protect them.”

Challenges to live up to a moral code are precisely what young Americans have been encountering in Iraq and Afghanistan. In his account of a 2003 combat deployment in Iraq, "Soft Spots," Marine Sgt. Clint Van Winkle writes of such an incident: A car carrying two Iraqi men approached a Marine unit and a Marine opened fire, putting two bullet holes in the windshield and leaving the driver mortally wounded and his passenger torn open but alive, blood- drenched and writhing in pain. The two Iraqis may have been innocent civilians. The Marines may have been obeying the strict rules of engagement, which govern when deadly force can be used (normally, in cases where the approaching car is a threat to American life and the driver refuses several warning signals to stop). But the damage was still done.

The only way to absorb such experiences, Van Winkle writes, was to “make it impersonal and tell yourself you didn’t give a shit one way or another, even though you really did. It would eventually catch up to you. Sooner or later you’d have to contend with those sights and sounds, the blood and flies, but that wasn’t the place for remorse. There was too much war left. We still had a lot of killing to do.”

In a recent phone interview, Van Winkle said the decade since his combat tour has given him a slightly different perspective. “I tried to make myself and my Marines live up to those moral standards,” he said. “I mean, we weren’t pushing people around. We weren’t doing things we shouldn’t have been doing, although things happened by accident.

“I was doing what I was supposed to be doing, and bad things still happened.”

His moral injury is not unique. “The bright line between murder and legitimate killing is something that our most junior enlisted person cares deeply about,” said Shay. “When they kill somebody who didn’t need to be killed, they are really wounded themselves.”

Not all those who deploy to a war zone experience killing or direct combat, and some troops never get to war at all. But moral injury can occur anywhere. Certainly the technicians working in mortuary affairs at Dover Air Force Base, Del., who handle the remains of Americans killed in combat are exposed to moral trauma.

For many other U.S. troops, exposure to killing and other traumas is common. In 2004, even before multiple combat deployments became routine, a study of 3,671 combat Marines returning from Iraq found that 65 percent had killed an enemy combatant, and 28 percent said they were responsible for the death of a civilian. Eighty-three percent had seen ill or injured women or children whom they were unable to help. More than half – 57 percent – had handled or uncovered human remains.

The intense kinship forged among small-unit combat troops can enable them to endure hardship, loneliness and peril. But such close relationships also put them at risk of excruciating grief at the sudden, violent death of a loved comrade, something that happens all too frequently. In a 2013 Wounded Warrior Project survey of its members, all severely wounded combat veterans, 80 percent said they had a friend seriously wounded or killed in action.

Dr. William Nash and Stephen Canty join HuffPost Live to talk about the bond that is forged among fellow soldiers.

In a similar finding, an extensive 2008 field survey of combat and support troops in Iraq and Afghanistan found that two-thirds knew someone seriously injured or killed. Fifty-six percent had a member of their unit wounded or killed.

‘The Right Thing To Do Could Get You Killed’

In retrospect, signs of the resulting moral confusion are difficult to miss. The rate at which troops were hospitalized for mental illnesses has risen 87 percent since 2000, according to a July 2013 study by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. The center also reported in June of last year that mental complaints, not physical injury, were the leading cause of medical evacuations from the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan between 2001 and 2012.

Michael Castellana, a psychotherapist at the U.S. Naval Medical Center in San Diego, sees the damage among dozens of his Marine patients: an erosion of moral certainty, or the confidence in their sense of right and wrong. “We are beginning,” he told me, “to venture into what I think is the kernel of combat trauma: the transformative capacity of what happens when we send our children into a war zone and say, ‘Kill like a champion.’”

Nash, the retired Navy psychiatrist, said veterans looking back on their time in Iraq or Afghanistan are prone to wonder, “In my little sphere of influence, how well did I or didn’t I live up to the ideals?” Often, he said, the answer “is what kills them.”

The inability to consistently achieve the highest levels of moral behavior in the shambles and chaos of war can produce varying degrees of “shame and guilt and anger – the primary emotional consequences of this moral injury,” Castellana said. “And if you read the suicide notes, the poems and writings of service members and veterans, it’s the killing; it’s failing to protect those we’re supposed to protect, whether that’s peers or innocent civilians; it’s sending people to their death if you’re a leader; failing to save the lives of those injured if you’re a medical professional. ... Nothing to do with the rightness or wrongness of war.”

In recent years, the military has tried to build what it calls “resiliency” into its young warriors. In one Army program, Comprehensive Soldier Fitness, soldiers at every level get annual training in physical and psychological strengthening. The key to absorbing stress and moral challenges is to “own what you can control, and think before you take on negative thoughts and start blaming yourself,” said Sgt. 1st Class Eric Tobin, a master resilience trainer.

If women and children are inadvertently killed in battle, he said, “feeling bad about that is normal. Not to minimize the loss of life, but you can also focus on the positive outcomes of that battle, that you are still alive, that you protected yourself and your team, that you helped the military achieve its objective.”

The Army is also producing a series of videos to get troops to think about moral injury before they are sent into battle. In four of these 30- minute videos, to be completed later this spring, combat veterans talk about their experiences and how they dealt with the psychological damage, said Lt. Col. Stephen W. Austin, an Army chaplain with the Comprehensive Soldier Fitness program. One of the videos focuses on killing.

“There are no answers – we just want to start the conversation, getting the troops comfortable talking about these things,” said Austin. “That’s the most important thing of all, that people feel they can talk about these issues with their buddies.”

The Marines have taken a slightly different approach, focused on identifying and helping Marines with all forms of combat stress right on the battlefield.

Nash developed a comprehensive approach to combat stress called OSCAR (Operational Stress Control and Readiness) concepts. Under the program, the Marines have embedded mental health professionals like himself directly into combat battalions. And leaders, officers and noncommissioned officers alike, were trained to recognize Marines under severe stress and to intervene, removing them from battle if necessary, getting them calmed down and getting them peer support so they wouldn’t isolate themselves, and getting higher-level help if needed.

“This is relevant to moral injury big-time,” said Nash. It’s on-the-spot help from compassionate and wise mentors, the people who know Marines the best. A good platoon sergeant or squad leader is “better than I ever could be, listening to a Marine’s story, saying, ‘I’ve been there and done that and I made sense of it by saying this part was my responsibility but all that other stuff I couldn’t help.’”

The best military leaders do this instinctively. In Iraq, Nash once watched a battle commander lean over a wounded Marine being carried off on a gurney; like most of the wounded, he was not only in extreme pain and fear, but tormented with shame for having been wounded, and guilt at having to leave his buddies. “You did your job,” the commander said, “and I am proud of you.”

The military’s efforts to build “resiliency” in its troops has drawn criticism from the Institute of Medicine, the independent, nongovernmental health arm of the National Academies. In a new report published in February, the IOM said there is an “urgent need” to prevent psychological health problems in the military, but that the Pentagon’s prevention programs are “not consistently based on evidence” and there is “no systematic use of national performance standards” to assess their effectiveness.

A more focused effort to help troops think through ethical and moral problems is a virtual reality (VR) prototype designed by Albert “Skip” Rizzo, a University of Southern California psychologist and specialist in virtual reality at the school’s Institute for Creative Technologies.

In one VR scenario, troops on a routine patrol halt their convoy, confronting a man drawn up in a fetal position on the road. As they watch, he moves slightly – he’s alive. Young soldiers are saying, “Hey! Let’s go help!” But they are silenced by the sergeant, who warns them that this may be an ambush.

“That guy may be innocent,” the sergeant says, “Or he may have a pound of C4 [explosive] on him. Maybe he’s just lyin’ there waitin’ for us to get near, and he or one of his buddies in that village hits the switch and boom! You’re dead – or if you’re lucky, you’re laying in the ditch with no arms or legs. ... I’ve seen it happen. Sometimes, life sucks.”

The soldiers call for a robot to investigate, but while they wait, a friendly and wise mentor appears on the screen. “I’m Capt. Branch. My job is to turn up at key moments to help you develop the resilience you will experience in and around combat,” he says in an avuncular tone. “Today you stood by and did nothing while a man bled to death on the roadway. How’d that feel? Wrong? Frustrating? Overwhelming? It sucked, didn’t it? This kind of twisted crap happens all the time here. Your natural impulses are going to be challenged at every turn.”

The scenarios are intended not to provide specific answers, but to introduce troops to morally ambiguous situations and to get them thinking and talking about how to deal with them. But the bottom line is that morality, in war, is different.

“What you’ve learned from every good and decent person in your life is sometimes going to have to go on the back burner,” says the Capt. Branch character. “The right thing to do in San Diego or Charlotte ... could get you killed here.”

This virtual reality prototype is designed to help troops confront and talk about morally challenging situations in wartime. It was created by University of Southern California psychologist Albert “Skip” Rizzo, a specialist in virtual reality at the school’s Institute for Creative Technologies.

Whether or not the VR scenarios help troops prepare for combat is unclear. But some answers may come from a pilot project Rizzo is running with a Colorado National Guard special operations team scheduled to deploy to Afghanistan later this year. The project is underwritten by the U.S. Army Research Lab, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the Infinite Hero Foundation, which supports troops and veterans with physical and mental health issues.

Rizzo and his team are using the virtual reality scenarios to study soldiers’ reactions to moral challenges, monitoring each participant’s heart rate, respiration and skin conductivity, and drawing blood to check for stress biomarkers.

“The problem we’re trying to understand is, can we detect people who may have more difficulties with moral and ethical quandaries that happen every day in combat,” Rizzo said. “And whether exposure to these scenarios has an impact” on how soldiers absorb combat trauma.

Such work may begin to provide critical insights into the nature of moral injury and help identify individuals who are more vulnerable to it. But for now, young troops will go to war not fully prepared for what they’ll find.

“None of us really knows what it’s like until we go over there, and we go two, three, four, five times before we ever pause to think about what we’re doing,” said Canty, who is now out of the Marine Corps.

“There’s always going to be people like me who are smiling the first time they get on the bus [to boot camp] – they don’t want to miss the war,” he said. “There will always be kids willing to fight, and they’re always going to pay this price, and there are always going to be guys like me who are saying, ‘Hey man, you don’t wanna do it, no, no, no, you don’t want to. It seems like fun, and I can’t tell you not to do it.’ But there’s no talking a kid out of it.”

Only after troops get back, he said, “do we start to look at the mental effects of killing other human beings.”

Canty’s little brother, Joe, joined the Marines in 2010 and recently deployed to Afghanistan. “I know what he’s getting into; he’s going back to Helmand Province less than 20 miles from where I was, and he’s got a grin ear to ear,” Stephen said. “And there’s nothing I can do to wipe that grin off his face because, that was me, you know? Three years earlier. Nobody could have told me.”

Stephen’s grandfather tried. He’d been a Marine in the Pacific in World War II. “Don’t do it,” he told Stephen before he enlisted at 17. “You’re too goddamn smart, boy.”

PART THREE: Healing - Can We Treat Moral Wounds?

Few life traumas can match the experiences of a medic in combat, or etch so deeply and painfully into a soul.

Billie Grimes-Watson was a medic in Iraq in 2003 and 2004. As the initial U.S. invasion turned into bloody chaos, she would sprint through through the smoke and fire of blasts from improvised explosive devices and gunfire to save lives, struggling with the maimed and broken bodies of soldiers she knew and loved. And try to recover in a few hours rest between missions.

She had just passed her 26th birthday.

Occasionally she would call home, but would burst into tears when she’d start to describe what she was doing. Then she stopped trying. A young officer in her platoon, Ben Colgan, was fatally wounded in a bomb blast. She was devastated. “I couldn’t help Lt. Colgan,” she told the military newspaper Stars and Stripes in 2004.

Nearly a decade later, Grimes-Watson is haunted by the war and her part in it, bearing moral injuries literally so unspeakable that she seems beyond help. “I avoid talking about it, try to keep it down,” she told me in a recent phone conversation. “But inside I’m trying to do the happy face so no one knows how much I’m hurting.”

Therapists and researchers are recognizing more and more cases of service members like Grimes-Watson who are returning from war with moral injuries, wounds caused by blows to their moral foundation, damaging their sense of right and wrong and often leaving them with traumatic grief.

Moral injuries aren’t always evident. But they can be painful and enduring.

“Everybody has demons, but there are some wild kind of demons when you come back from combat,” said a Navy corpsman (the Navy’s name for its medics) who served a tour each in Iraq and Afghanistan and asked not to be identified by name. He was once unable to save a Marine with a terrible head wound, and afterwards felt other Marines blamed him. “You come home and ask yourself, what the hell did I do all that for? You gotta live with that shit and there’s no program that the military can send you to or any class that’s really gonna help.

“Guilt is the root of it,” he said. “Asking yourself, why are you such a bad person?” He wasn’t that way before his military service. “I have a hard time dealing with the fact that I’m not me anymore.”

Marine Staff Sgt. Felipe Tremillo also is struggling with guilt. Two years after he came home from his second combat tour, Tremillo is still haunted by images of the women and children he saw suffer from the violence and destruction of war in Afghanistan. “Terrible things happened to the people we are supposed to be helping,” he said. “We’d do raids, going in people’s homes and people would get hurt.”

In Iraq, where Tremillo served his first combat tour, it was common for U.S. troops to search for weapons caches by banging on a door and ordering a family out of the house, holding them prone on the ground at gunpoint while rifling through their belongings. It was an oft- repeated scene, one that former four-star military commander Stanley McChrystal wrote in his memoir made him feel “sick.”

“As I watched I could feel in my own limbs and chest the shame and fury” of the helpless civilians, he wrote.

American soldiers had to act that way, Tremillo recognizes, “in order to stay safe.” But the moral compromise, the willful casting aside of his own values, broke something inside him, changing him into someone he hardly recognizes, or admires.

For many who experience such moral injury, the shock and pain fade over time. Supportive and understanding family and friends, a good job and often a spiritual connection can help.

For others, the wound gets worse. For Tremillo, “there is no fairytale ending,” he said.

“People try to make sense of what happened, but it often gets reduced to, ‘It was my fault,’ ‘the world is dangerous,’ or, in severe cases, ‘I’m a monster,’” explained Peter Yeomans, a staff psychologist at the VA Medical Center in Philadelphia. Many of his patients suffer from both Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and moral injury, and he is searching for ways to ease their pain.

“People mostly try to push those experiences away and not look at them, and they inevitably end up with an oversimplified conclusion about what it all meant,” he said. “We’re trying to get them to unearth the beliefs that are causing their distress, and then help them analyze it, consider the evidence for and against the way they see it, and ultimately develop a more nuanced belief about what happened and what their responsibility actually is.”

For most veterans with moral injury, there is little help. In contrast to the extensive training and preparation the government provides troops for battle, the Defense Department and the VA have almost nothing specifically for the moral wounds that endure after they return.

Only one small program, based at the San Diego Naval Medical Center, routinely provides therapy designed for moral injury. Several clinicians launched the program early in 2013 after realizing that many of their PTSD patients needed a different kind of help.

The therapies and drugs developed to treat PTSD don’t get at the root of moral injury, experts say, because they focus on extinguishing fear. PTSD therapy often takes the form of asking the patient to re-live the damaging experience over and over, until the fear subsides. But for a medic, say, whose pain comes not from fear but from losing a patient, being forced to repeatedly recall that experience only drives the pain deeper, therapists have found.

“Medication doesn’t fix this stuff,” said Army psychologist John Rigg, who sees returning combat troops at Fort Gordon, Ga. Instead, therapists focus on helping morally injured patients accept that wrong was done, but that it need not define their lives.

On the battlefield, some have devised makeshift rituals of cleansing and forgiveness. At the end of a brutal 12-month combat tour in Iraq, one battalion chaplain gathered the troops and handed out slips of paper. He asked the soldiers to jot down everything they were sorry for, ashamed of, angry about or regretted. The papers went into a makeshift stone baptismal font, and as the soldiers stood silently in a circle, the papers burned to ash.

“It was sort of a ritual of forgiveness,” said the chaplain, Lt. Col. Doug Etter of the Pennsylvania National Guard. “The idea was to leave all the most troubling things behind in Iraq.”

But by and large, those with moral injury are on their own.

David Wood and Debbie Schiano join HuffPost Live to discuss the steps for treating soldiers suffering from moral injuries.

‘A Touchy Subject’

Brett Litz, a clinical psychologist and professor at Boston University who is affiliated with the VA in Boston, has done pioneering work in defining and treating moral injury. “We have no illusion of quick-fix cure for serious and sustained moral injury,” he said.

A few academic researchers and therapists scattered across the country are experimenting with new forms of therapy, some adapting ideas that have worked with patients suffering from PTSD and other forms of war trauma. The Pentagon has quietly funded a $2 million clinical trial, led by Litz, to explore ways to adapt PTSD therapies for Marines suffering from moral injury.

The military services, not surprisingly, are reluctant to discuss moral injury, as it goes to the heart of military operations and the nature of war. The Army is producing new training videos aimed at preparing soldiers to absorb moral shocks long enough to keep them in the fight. But the Pentagon does not formally recognize moral injury, and the Navy refuses to use the term, referring instead to "inner conflict."

“That’s a euphemism,” snorted retired Marine Maj. Gen. Thomas S. Jones, a decorated combat veteran who has had to raise his own money for research into combat stress, moral injury and treatment for wounded Marines. “It is true the folks are loath to use the word ‘moral,’” he said of military brass. Those outside the military “will think it means somebody did something immoral,” which may not be the case, he said.

The Pentagon declined to make policymaking officials available to discuss moral injury. Instead, Defense Department spokeswoman Joy Crabaugh issued a statement observing that moral injury is “not clinically defined” and that there is no “formal diagnosis” for it. The statement said the Defense Department “provides a wide range of medical and non-medical resources for service members seeking assistance in addressing moral injuries.”

Mental health care providers “often address moral injury when treating a psychiatric disorder,” the statement said, and chaplains are available as well. Crabaugh would not say why Pentagon policymakers refused to discuss moral injury.

Litz accepts the military’s reluctance to recognize moral injury. “I’m very respectful of how difficult it is for them to embrace,” he said. “After all, service members have to follow orders, and if ordered to do something it is by definition legal and moral.” Difficult problems might arise from official recognition of moral injury: how to measure the intensity of the pain, for instance, and whether the government should offer compensation, as it does for PTSD.

“Moral injury is a touchy topic, and for a long time [mental health care] providers have been nervous about addressing it because they felt inexperienced or they felt it was a religious issue,” said Amy Amidon, a staff psychologist at the San Diego Naval Medical Center who oversees its moral injury/moral repair therapy group. “And service members have been very hesitant to talk about it, nervous about how it would affect their career.”

But things are changing. As recently as 2009, Litz was writing that despite evidence of a rising tide of moral injury among troops from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, clinicians and researchers were “failing to pay sufficient attention” to the problem, that “questions about moral injury [were] not being addressed,” and that clinicians who came across cases of moral injury were “at a loss” because existing therapies for PTSD were not designed to address moral injury directly.

In a recent phone conversation, however, Litz said moral injury has become a significant area of interest among clinical scientists. “What’s new is that we are trying to study it in a more scientific way and finding ways of treating moral injury – and that’s unprecedented. It’s a slow process, and I am very proud of the fact that we have brought science to bear,” he said. Speaking of the results of new research on experimental therapies, he added: “You can’t argue with a clinical trial.”

‘I See Incredible Goodness’

At the San Diego Naval Medical Center, the eight-week moral injury/moral repair program begins with time devoted simply to allowing patients to feel comfortable and safe in a small group. Eventually, each is asked to relate his or her story, often a raw, emotional experience for those reluctant to acknowledge the source of their pain. The idea is to drag it out into the open so that it can be dealt with.

The group is instructed to listen and respond with support but not judgment, neither condemning nor excusing what happened. Whatever caused the moral injury, Amidon said, “we are not going to brush it aside. It did happen and it wasn’t OK. The point is to help them feel OK sitting in the darkness with the evil they experienced.”

Often, patients feel guilty or ashamed, convinced they are unforgiven, worthless and impure.

In one recent session, a soldier rose hesitantly and told of a firefight in Iraq. Insurgents had suddenly rushed toward him using women and children as shields. “He had about three-quarters of a second to decide, and of course he killed,” Michael Castellana, a staff psychotherapist and co-facilitator of the group, recounted.

“When he arrived home, coming off the plane, his wife handed him his new baby daughter. She put the baby in his arms and he immediately gave the baby back to her with an almost disgusted look – he almost dropped her,” he said. “The thing was, his new daughter was so beautiful and perfect and pure that he didn’t want his filth to contaminate her.

“As terrible as some of this stuff is – and sometimes what we hear makes your toes curl – what I see in these people is incredible goodness,” Castellana said. “Their efforts to punish themselves is just further evidence of their goodness.”

Further into the sessions, group members are encouraged to do community service, and to practice acts of kindness. “One of the consequences of moral injury is self-isolation,” said Amidon. “The idea here is for them to begin to recognize the goodness in themselves, and to reinforce their sense of being accepted in the community.”

Toward the end of the eight weeks, group members are invited to write a letter to themselves from a benevolent figure in their lives – a spouse, or grandfather, or mentor – to explain how they feel and to imagine what this person would say in response.

“What is really healing,” Amidon said, “is to hear, whether it’s in this imagined conversation or with the others, someone sharing really shameful experiences and having people accept them – saying, ‘Yeah, that was fucked up, what you did, and remember all the good things you’ve done. This doesn’t have to define the rest of your life.’”

One participant, now 33, struggles with the guilt of having killed the wrong person. “My big thing was taking another man’s life and finding out later on that wasn’t who you were supposed to shoot,” he told me, asking not to be identified because of his continuing psychological treatment. “The [troops] out there, they don’t talk about it. They act like it never happened. Completely don’t ever bring it up.”

But in the San Diego moral injury program, he did summon the courage to stand up and talk about it. “Just saying it was helpful,” he said later. “There were about five people in the room, and they got it. I didn’t need to have anyone say it’s OK, because it’s not OK – that would have just pissed me off.”

What was the response of his peers? “It was silence,” he said. “That unsaid, ‘I don’t care what you did, we are still good.’

“People give you space. And they got a therapy dog in there, and he comes over and wags his tail a little bit, tells you it’s OK, too, you know? Not saying it’s OK, but just to say you’re not some wicked person.”

Felipe Tremillo, the Marine staff sergeant, took part in the San Diego program last fall. One assignment was to write an imaginary letter of apology. His was intended for a young Afghan boy whom he had glimpsed during a raid in which Marines busted down doors and ejected people from their homes while they searched inside for weapons. The boy had stood trembling as Tremillo and the Marines rifled through the family possessions, his eyes, Tremillo felt, blazing shame and rage.

“I didn’t know his name,” Tremillo said. But in his letter, “I told him how sorry I was at how I affected his life, that he didn’t have a fair chance to have a happy life, based off of our actions as a unit.” Writing the letter, he said, “wasn’t about me forgiving myself, more about accepting who I am now.”

Former Navy psychiatrist William P. Nash takes a slightly different approach in the experimental sessions he runs. His pioneering work with moral injury grew out of his experience as a combat therapist deployed with Marines in Iraq. Nash has developed a Moral Injury Events Scale, a self- evaluation for troops that asks them to respond to statements such as “I saw things that were morally wrong,” or “I am troubled by having acted in ways that violated my own morals or values,” or “I feel betrayed by leaders I once trusted.”

But from there, drawing out the painful, detailed explanations can be difficult.

“When they come in for treatment, the first thing out of their mouth is not, ‘I did something unforgivable and I want to tell you about it.’ Because they are working as hard as they can not to think about it,” Nash said. “They don’t know that you are not going to judge them. They may be on their last little thread of self-acceptance and they don’t want you to cut the thread."

To reach them, Litz, Nash and others who have tried this approach to moral injury use a technique they call adaptive disclosure. In this therapy, patients are asked to briefly discuss what caused their moral injury. Among combat Marines, often the cause is the discovery that they love the thrill of combat and killing, followed by guilt for feeling that way, Nash said.

As in the San Diego program, patients are asked to imagine they are revealing their secret to a compassionate, trusted moral authority – a coach or priest. “The assumption here is if there is someone in your life who has your back, cares for you, is compassionate and you have felt their love for you, then you are safe in disclosing what you did or failed to do,” Litz explained. “If there is that compassionate love, that forgiving presence, it will kick-start thinking about, well, how do you fix this, how can you lead a good life now?” And that, he said, “is the beginning of self-compassion.”

The adaptive part of the therapy involves helping the patient accept his or her past actions. Yeah, I did this, or I saw this, or this really happened – but it’s not all my fault and I can live with it. Patients are asked to make a list of everyone, every person and institution, that bears some responsibility for their moral injury. They then assign each a percentage of blame, to add up to 100 percent. If a Marine shot a child in combat, he might accept 30 percent of the blame. He might award the Taliban 50 percent, the child himself 5 percent and the Marine Corps 5 percent. God, perhaps, 10 percent.

A variant of adaptive disclosure was used in experimental treatment led by Litz and Maria Steenkamp, a clinical research psychologist at the Boston VA medical center, working with Marines from Camp Pendleton, Calif.

After having patients describe in painful detail what caused their moral injury, therapists asked them to choose someone they saw as a compassionate moral authority and hold an imaginary conversation with that person, describing what happened and the shame they feel. They were then asked to verbalize the response, using their imagination. Inevitably, patients imagined being told they were a good person at heart, that they were forgiven, and that they could go on to lead a good life. Of course, these conversations rely on imagination. But the technique allows the patient to articulate in his or her own words an alternative narrative about his injury.

All these approaches are designed as quick interventions, specifically intended for combat troops who may be deployed again soon. The goal is to provide patients with insights and techniques to continue the work on their own – and eventually to move beyond their injury.

Left alone, Nash said, veterans with moral injury either conclude that “none of this is my fault,” or “it’s all my fault.” Neither can be totally true.

“In your heart of hearts, you know you were the one who pulled the trigger. You can’t unring the bell, can’t undo what was done. And that’s a time bomb,” he said. But when patients are helped to recognize their true share of the blame, “you can begin to make amends, until you get to a point where you can forgive, and that’s the ultimate challenge.”

“To be clear, what we don’t do is to impose our moral appraisals or judgments [on] the situation, though we may occasionally have them,” Matt J. Gray, a University of Wyoming psychologist, said in an email. Gray led a 2012 study on therapy for moral injury and traumatic loss among 44 Marines. “We don’t try to dispute, minimize or explain away” a morally questionable action, he said. “We try to help the person understand that this action or inaction need not be destiny.”

Does this method actually work? The results are promising but not conclusive, in part because the studies conducted so far were designed as intense, short-term interventions with troops preparing to go back to war. True healing of a moral injury seems to take time.

“I don’t think it ever happens in the therapy,” Nash said, “because I don’t think the therapy is ever long enough for that to happen. All we can do is plant seeds.” But, he added, “as far as I know that’s the only route to salvation, and it ain’t easy and it ain’t quick.”

That was the conclusion of Gray’s clinical research trial in which adaptive disclosure therapy was used with 44 active-duty combat Marines with PTSD and moral injury. In six 90-minute sessions, Gray found that the Marines experienced “substantive” improvement in their symptoms. So substantive, in fact, that the study has been expanded to a five-year randomized clinical trial.

But success requires a long-term commitment, Gray wrote in a paper about the project. The six sessions “represented the beginning of a process that the Marine would need to continue after the formal conclusion of the intervention.”

Billie Grimes-Watson’s experience in therapy, last spring in the San Diego moral injury/moral repair group, underscores how long it can take to heal moral injury. Like others, she found it difficult in those sessions to describe her deepest wounds.

“I have more than one moral injury and I used the easier one and not the bad ones that are really affecting me,” she said in December, eight months after she completed the program.

What she told the group was “my small one,” about the Iraqi kids who would flock around U.S. troops and vehicles on patrol, begging for candy and cigarettes. As 2003 wore on, many of the kids in Baghdad turned sour, throwing rocks at American troops. Some troops started throwing rocks back.

“You could actually see them get hit pretty hard,” she said. “It’s something I normally wouldn’t do, bullying kids – I have kids of my own, and I can’t even think of anyone hurting them like I did with those kids.”

In therapy, she said, “I explained how peer pressure kind of gets to you and you do things you shouldn’t have done and you try to forgive yourself for it. People gave me hugs, a lot of crying and discussion. But I still feel guilty and I haven’t forgiven myself for a lot of the things I did over there.”

Now she is back home at Schofield Barracks in Hawaii, awaiting her discharge from the Army after 13 years. She’s been diagnosed with PTSD and physical ailments, but it’s the moral injuries that are truly disabling.

“I have all this guilt inside me and I want to let it out but I can’t,” she said. “I want to tell my husband and family what’s going on, but I don’t. I just put on a happy face until I’m alone.”

She’s been seeing a therapist since she returned from San Diego last spring, but she has not been able to even hint at her deeper injuries. Instead, she said, “I’ve started going backwards again. All the emotions and nightmares are coming back. I had stopped drinking and now I’m drinking again, trying to hide it. I can’t sleep at night.”