Till Death Do Us Part

This comprehensive five-part print and multimedia series exposes South Carolina as a state where more than 300 women died from domestic abuse over the past decade while political leaders did little to stem the violence. Judges called “Till Death Do Us Part” “extraordinarily powerful,” “so thoroughly reported and well written as to feel like the definitive work on domestic violence in South Carolina.” Originally published in the Post & Courier in August, 2014.

Click here to watch a supplemental video series featuring survivors of domestic violence.

PART ONE

More than 300 women were shot, stabbed, strangled, beaten, bludgeoned or burned to death over the past decade by men in South Carolina, dying at a rate of one every 12 days while the state does little to stem the carnage from domestic abuse.

More than three times as many women have died here at the hands of current or former lovers than the number of Palmetto State soldiers killed in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars combined.

It’s a staggering toll that for more than 15 years has placed South Carolina among the top 10 states nationally in the rate of women killed by men. The state topped the list on three occasions, including this past year, when it posted a murder rate for women that was more than double the national rate.

Awash in guns, saddled with ineffective laws and lacking enough shelters for the battered, South Carolina is a state where the deck is stacked against women trapped in the cycle of abuse, a Post and Courier investigation has found.

Couple this with deep-rooted beliefs about the sanctity of marriage and the place of women in the home, and the vows “till death do us part” take on a sinister tone.

The beat of killings has remained a constant in South Carolina, even as domestic violence rates have tumbled 64 percent nationwide over the past two decades, according to an analysis of crime statistics by the newspaper. This blood has spilled in every corner of the state, from beach towns and mountain hamlets to farming villages and sprawling urban centers, cutting across racial, ethnic and economic lines.

Consider 25-year-old Erica Olsen of Anderson, who was two months pregnant when her boyfriend stabbed her 25 times in front of her young daughter in October 2006. Or Andrenna Butler, 72, whose estranged husband drove from Pennsylvania to gun her down in her Newberry home in December. Or 30-year-old Dara Watson, whose fiancé shot her in the head at their Mount Pleasant home and dumped her in a Lowcountry forest in February 2012 before killing himself.

Interviews with more than 100 victims, counselors, police, prosecutors and judges reveal an ingrained, multi-generational problem in South Carolina, where abusive behavior is passed down from parents to their children. Yet the problem essentially remains a silent epidemic, a private matter that is seldom discussed outside the home until someone is seriously hurt.

“We have the notion that what goes on between a couple is just between the couple and is none of our business,” said 9th Circuit Solicitor Scarlett Wilson, chief prosecutor for Charleston and Berkeley counties. “Where that analysis goes wrong is we have to remember that couple is training their little boy that this is how he treats women and training their little girl that this is what she should expect from her man. The cycle is just perpetual.”

A lack of action

South Carolina is hardly alone in dealing with domestic violence. Nationwide, an average of three women are killed by a current or former lover every day. Other states are moving forward with reform measures, but South Carolina has largely remained idle while its domestic murder rate consistently ranks among the nation’s worst.

Though state officials have long lamented the high death toll for women, lawmakers have put little money into prevention programs and have resisted efforts to toughen penalties for abusers. This past year alone, a dozen measures to combat domestic violence died in the Legislature.

The state’s largest metro areas of Greenville, Columbia and Charleston lead the death tally in sheer numbers. But rural pockets, such as Marlboro, Allendale and Greenwood counties, hold more danger because the odds are higher there that a woman will die from domestic violence. These are places where resources for victims of abuse are thin, a predicament the state has done little to address.

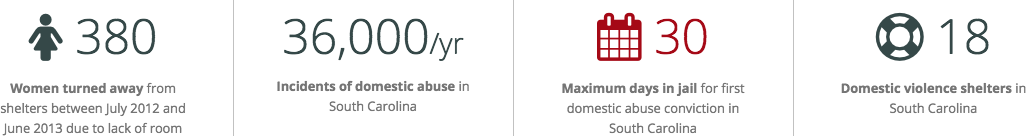

All 46 counties have at least one animal shelter to care for stray dogs and cats, but the state has only 18 domestic violence shelters to help women trying to escape abuse in the home. Experts say that just isn’t enough in a state that records around 36,000 incidents of domestic abuse every year. More than 380 victims were turned away from shelters around the state between 2012 and 2013 because they had no room, according to the state Department of Social Services.

Oconee County, in South Carolina’s rural northwest corner, realized it had a problem last year after six people died over six months in domestic killings. The sheriff pushed for the county to open a shelter after 58-year-old Gwendolyn Hiott was shot dead while trying to leave her husband, who then killed himself. She had nowhere to go, but the couple’s 24 cats and dogs were taken to the local animal shelter to be fed and housed while waiting for adoption.

When asked, most state legislators profess deep concern over domestic violence. Yet they maintain a legal system in which a man can earn five years in prison for abusing his dog but a maximum of just 30 days in jail for beating his wife or girlfriend on a first offense.

Many states have harsher penalties. Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee, for example, set the maximum jail stay for the same crime at six months. In Georgia and Alabama it is a year.

This extra time behind bars not only serves as a deterrent but also can save lives, according to counselors, prosecutors and academics. Studies have shown that the risk of being killed by an angry lover declines three months after separation and drops sharply after a year’s time.

The casket of 6-year-old Samenia Robinson is laid to rest alongside those of her mother, Detra Rainey, 39, and three brothers in Hillsboro Brown Cemetery in 2006. Detra Rainey’s husband was accused of fatally shooting her and his stepchildren inside their North Charleston mobile home.

Wife beaters get lenient treatment

More than a third of those charged in South Carolina domestic killings over the past decade had at least one prior arrest for criminal domestic violence or assault. More than 70 percent of those people had multiple prior arrests on those charges, with one man alone charged with a dozen domestic assaults. The majority spent just days in jail as a result of those crimes.

A prime example is Lee Dell Bradley, a 59-year-old Summerville man accused of fatally stabbing his longtime girlfriend, Frances Lawrence, in late May. Despite two prior arrests for violating court orders meant to protect Lawrence, the longest Bradley ever stayed in jail for abusing women was 81 days. And that came only after he appeared before a judge on a domestic violence charge for the fifth time.

Then there is 55-year-old David Reagan of Charleston, who spent less than a year in jail total on three previous domestic violence convictions before he was charged with strangling a girlfriend in 2013 while awaiting trial on an earlier domestic violence charge involving the girlfriend.

The Post and Courier investigation also found:

- Police and court resources vary wildly across the state. Larger cities, such as Charleston, generally have dedicated police units and special courts to deal with domestic violence. Most small towns do not, making it difficult to track abusers, catch signs of escalating violence and make services readily available to both victims and abusers.

- Accused killers are funneled into a state court system that struggles with overloaded dockets and depends on plea deals to push cases through. Of those convicted of domestic homicides since 2005, nearly half pleaded guilty to lesser charges that carry lighter sentences.

- Guns were the weapon of choice in nearly seven out of every 10 domestic killings of women over the past decade, but South Carolina lawmakers have blocked efforts to keep firearms out of the hands of abusers. Unlike South Carolina, more than two-thirds of all states bar batterers facing restraining orders from having firearms, and about half of those allow or require police to seize guns when they respond to domestic violence complaints.

- Abusers get out of jail quickly because of low bail requirements. Some states, including Maryland and Connecticut, screen domestic cases to determine which offenders pose the most danger to their victims. South Carolina doesn’t do this.

- Domestic abusers often are diverted to anger-management programs rather than jail even though many experts agree that they don’t work. In Charleston, authorities hauled one young man into court in March after he failed to complete his anger-management program. His excuse: He had missed his appointments because he had been jailed again for breaking into his girlfriend’s home and beating her.

- Victims are encouraged to seek orders of protection, but the orders lack teeth, and the state has no central means to alert police that an order exists. Take the case of 46-year-old Robert Irby, who still had the restraining order paperwork in his hand the day he confessed to stalking and killing his ex-girlfriend in Greer in 2010. He gunned her down outside her home the day after he learned about the order.

- The vast majority of states have fatality-review teams in place that study domestic killings for patterns and lessons that can be used to prevent future violence. South Carolina is one of only nine states without such a team.

Legislative death

Located in the heart of the Bible Belt, South Carolina is a deeply conservative state where men have ruled for centuries. The state elected its first female governor four years ago, but men continue to dominate elected offices, judicial appointments and other seats of government and corporate power. In many respects, the state’s power structure is a fraternity reluctant to challenge the belief that a man’s home is his castle and what goes on there, stays there.

“Some of this is rooted in this notion of women as property and maintaining the privacy of what goes on within the walls of the home,” said state Rep. Gilda Cobb-Hunter, an Orangeburg Democrat. “And a lot of it has to do with this notion of gun rights as well. When all of those things are rolled into one, it tends to speak to why we rank so high in the number of fatalities.”

Against this backdrop, it has often been difficult to get traction for spending more tax dollars for domestic violence programs and bolstering protections for the abused. The only consistent state money spent on such programs comes from a sliver of proceeds from marriage license fees — a figure that has hovered for years around $800,000 for the entire state. That’s just a tad more than lawmakers earmarked this year for improvements to a fish farm in Colleton County. It equates to roughly $22 for each domestic violence victim.

“Even as we have gone up in the number of murders and attempted murders over the years, that support has never changed,” said Rebecca Williams-Agee, director of prevention and education for the S.C. Coalition Against Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault. “It’s all wrapped up in the politics of this state and the stereotypes of domestic violence victims. Why does she stay? Why doesn’t she pull herself up by her own bootstraps?”

Alicia Alvarez put up with abuse for years before she got the courage to leave. The Charleston mother of two said abusers create an atmosphere that robs victims of confidence.

Abusers don’t begin by hitting or killing, Alvarez said. “It begins with little criticisms, second-guessing everything you do. They get in your brain so that when they tell you, ‘You are worthless,’ you believe it.”

Just a few months after South Carolina’s most recent designation as the deadliest in the nation for women, the state’s Legislature took up about a dozen bills aimed at toughening penalties for abusers, keeping guns out of their hands and keeping them away from their victims.

The bills languished in committees and died, with the exception of a lone provision that aims to protect the welfare of family pets left in the care of a person facing domestic abuse charges.

Five of those measures got stuck in the Senate Judiciary Committee, a panel filled with lawyers. Its chairman is Larry Martin, a Republican from Pickens County, where nine domestic killings occurred over the past decade.

Martin wasn’t sure why the bills failed to advance, but he stressed that he is a strong supporter of measures to reduce domestic abuse. He said lawmakers had approved meaningful legislation on the topic in recent years and that the measures had a powerful impact, though he couldn’t recall what those bills were.

“I promise you there is no effort to hold anything up,” he said. “We are generally supportive of legislation that helps reduce the horrible statistics we have each year on domestic violence.”

If so, Cobb-Hunter hasn’t seen it. She pushed a proposal to require abusers to surrender their firearms if convicted of domestic violence or facing a restraining order. The proposal went nowhere after running headlong into the state’s powerful gun lobby in an election year, she said.

“You put those two things together and you see the results — nothing happens. But, at the same time, families are being destroyed by this violence. That shouldn’t be acceptable to any of us.”

State Rep. Bakari Sellers’ proposal to stiffen penalties for first-time domestic violence offenders met a similar fate. The Democrat from Denmark, who is running for lieutenant governor, said some of his fellow House Judiciary Committee members seemed more intent on blaming victims for staying in abusive relationships than in giving the bill a fair airing.

“It’s a big issue statewide, but people were just indifferent,” Sellers said. “The sad part is that women will die.”

After several calls to legislators from The Post and Courier, House Speaker Bobby Harrell contacted the newspaper in early June to say he was disappointed the session had ended with no action on domestic violence reform. The Charleston Republican pledged to appoint an ad hoc committee, led by a female lawmaker, to study the issue prior to the next legislative session and chart a path for change. No appointments had been made by Monday, but they were said to be in the works.

This time, Harrell said, things will be different.

Paulette Sullivan Moore, vice president of public policy for Washington, D.C.-based National Network to End Domestic Violence, said curbing domestic violence is possible with good laws and systems for protecting women. But South Carolina’s lingering presence among the top states for domestic homicides shows the state isn’t getting the job done, she said.

“To be in the top 10 states for so many years is pretty significant,” she said. “I think that says the state needs to take advantage of this opportunity to craft good policy and legislation to ensure that it is not failing half of its population.”

If history holds true, 30 more women will be dead by the end of the next legislative session in June 2015, when lawmakers have another chance to stem the violence.

The thin line

Every year, people from across South Carolina gather at the Statehouse in Columbia to remember those killed in domestic violence, a somber ceremony marked by the reading of names and tolling of bells.

Politicians, prosecutors and other advocates repeat calls for an end to the bloodshed and proclaim criminal domestic violence the state’s No. 1 law enforcement priority.

Poets, scholars and philosophers have long rhapsodized about the thin line separating love from hate, a delicate thread that, when bent, can fuel a ravenous passion for reckoning and retribution. All too often in South Carolina, this ends with women paying the ultimate price.

That was the case just before Christmas 2011, when Avery Blandin, 49, stalked through the front of a Wal-Mart store in suburban Greenville County, seething with rage and carrying a 12-inch knife tucked into the waistband of his slacks.

Built like a fireplug and prone to blowing his stack, Blandin marched into the bank inside the store where his wife Lilia worked and began shouting. He jerked her onto a table and pulled out his knife, stabbing her again and again. When she slumped to the floor, he stomped on her head and neck.

Lilia died within the hour. She was 38.

Blandin had used his wife as a punching bag for years. She had filed charges against him, sought orders of protection and slept in her car to keep him at bay. But none of that stopped him from making good on his threats to kill her that December day.

“I loved her,” Blandin told an Upstate courtroom after pleading guilty to her murder. “She was my wife, my best friend.”

.jpg)

PART TWO: Legislative Inaction

Becky Callaham stepped onto the South Carolina Statehouse grounds, filled with optimism, to support a proposed law that would provide better protections for victims of domestic violence. She thought lawmakers would be stirred to action by the national scorn the state has received since September when it was ranked No. 1 in the nation in the rate of women killed by men.

Callaham, executive director of Safe Harbor, a Greenville-based women’s shelter, figured legislators might finally be ready to pass a new law aimed at stemming the carnage.

“I felt like we really could get something done.”

She left the March 27 hearing with her hope all but shattered. She didn’t know the legislators on the panel, but one of them asked her a question that referred to female victims as “those types of people.”

Her mouth fell open in shock at the attitude she thought had died long ago.

And she watched the bill get dismembered as its sponsors tried in vain to win over lawmakers with objections about gun restrictions, increased sentences and the legal rights of accused abusers.

The bill’s provision for the surrender of firearms was dropped and the proposal for a maximum 180-day sentence on first conviction was cut to 60 days.

“It got chipped away to nothing, then died,” Callaham said. “I was so frustrated. I was naive.”

Becky Callaham, executive director of Safe Harbor, a Greenville-based shelter and counseling center for women, said she felt naive and frustrated after her high hopes for legislative action on domestic violence were dashed by the General Assembly this year.

A trail of death and inaction

The bill Callaham supported was filed Dec. 3, the first of seven proposed laws in what appeared to be a major effort by lawmakers to tackle the state’s status as the nation’s most deadly for women.

By the time the bill was formally introduced a month later at the opening of the 2014 legislative session, 72-year-old Andrenna Butler would be found by a neighbor dead on the floor of her Newberry home. She had a bullet in her head from what police described as a domestic dispute with her ex-husband of 50 years.

Before the first words of the bill were read on the House floor, five other South Carolina residents would die, also victims of domestic violence.

And the day after the bill was read and referred to the House Judiciary Committee for review, Sheddrick Miller armed himself with a handgun in his suburban Columbia home not far from the Capitol building. The 38-year-old methodically went from bedroom to bedroom, shot his two children, ages 3 and 1, in their heads, then killed his wife, Kia, and took his own life. Police described it as a tragic explosion of domestic violence.

None of these killings seemed to resonate much inside the halls of the Statehouse. In fact, one month after Miller obliterated his family 11 miles from the Senate floor, lawmakers approved a measure to expand gun rights, allowing people to carry loaded, concealed weapons into a bar or restaurant.

By the end of that month, all seven of the new domestic violence bills would be referred for study to either the House or Senate Judiciary committees. There, they joined five other proposed domestic violence laws left over from the previous year’s legislative session.

Both committees are filled with lawyers, many of whom practice criminal defense and are inherently suspicious of attempts to ratchet up penalties for offenders. The committees also are loaded with men. The 23-member Senate Judiciary Committee has only one woman. The House Judiciary has 25 members, of which five are women. And the subcommittee Callaham testified before contains no female members.

Rep. Bill Crosby, a Charleston Republican who pushed another measure to combat domestic violence, said many of the members on the committee are attorneys, “and they typically argue against strong penalties.”

If proposals make it out of these committees, they stand a decent chance of becoming law. But the committees also function like a legislative purgatory of sorts, a black hole in the process where unpopular bills languish in a limbo state until the clock simply runs out. In this manner, no one is required to take a stand and no up-or-down vote need take place. Committees instead adjourn debate, and the proposal just goes away with no record of why or who’s responsible.

The last time the Legislature took a stab at strengthening domestic violence laws was a decade ago when fines and sentences were increased for repeat offenders. Lawmakers also added a mandatory one-year sentence for those convicted of domestic violence of a “high and aggravated” nature.

Opponents of those changes argued at the time that the increased penalties might result in people being arrested on lesser charges, such as assault. But a 2007 study by the state Office of Research and Statistics showed no substantive change.

More needs to be done

All of the legislators interviewed by The Post and Courier about South Carolina’s deadly ranking for women agreed something more needs to be done to stem the brutality. But, they said, it often takes time to reach compromises to create workable laws.

It’s time many women don’t have, Callaham said.

In the two months between Miller’s deadly rampage and Callaham’s testimony in the House committee, seven more South Carolinians died from domestic violence, including 24-year-old Jeremy Williamson of North.

Williamson had been implicated in two earlier incidents of domestic violence for which he was not arrested. And he was awaiting trial on a charge of criminal domestic violence for a third incident when he got into an argument with his girlfriend, Shayla Davis, 23, in the early morning hours of Feb. 2.

Police said Davis tried to leave, but Williamson dragged her back into the house, punched the back of her head and threw her to the floor. She struggled to her feet, grabbed a gun and ordered him to leave, but he lunged for her and took a bullet to his stomach.

Williamson died shortly after at a hospital. Orangeburg County Sheriff Leroy Ravenell called the killing justified because Davis was in fear for her life.

Ravenell labeled it another example of the epidemic of domestic violence sweeping the state.

“We must take steps now to improve a victim’s ability to get the resources necessary to better manage and eventually leave these relationships,” the sheriff told The (Orangeburg) Times and Democrat.

Democratic Rep. Bakari Sellers of Denmark says he will try again next year to win approval of his bill to strengthen the state's domestic violence laws. His bill, and 11 others to bolster those laws, died without a vote in the last legislative session.

Brought to tears

Similar sentiments drove Democratic Rep. Bakari Sellers of Denmark to sponsor the bill Callaham went to the capitol to support. Sellers said he drafted the measure after attending October’s “Silent Witness” ceremony, a somber gathering in which the names of those killed in domestic violence the previous year are read aloud. It’s an effort by the state Attorney General’s Office to call attention to the macabre toll.

As name followed name, “I literally cried,” Sellers said.

Sellers said he believes his bill did not get an honest consideration from the House Judiciary’s Criminal Laws Subcommittee. He wouldn’t name the lawmaker but said one expressed dismissive questions that blame women for not leaving their abusers.

Several people who were at the hearing, but didn’t want their names used because they have to appear before the committee, identified the panel member as Republican Rep. Eddie Tallon of Spartanburg.

Tallon is a retired SLED agent who is known in the Legislature as an advocate for law enforcement and public safety issues.

“I’m the law-and-order guy on that committee,” Tallon said. “I can’t imagine me saying anything. ... If something was said, it was not said in a derogatory manner.”

As far as domestic violence is concerned, he said, “We certainly have a problem. Anything we can do to help stem it, we need to do.”

Sellers said the Legislature needs to do just that, fix it. He said that as a lawyer who has defended male and female abusers, he’s seen the system’s problems and believes his bill would have gone a long way toward solving those problems, especially with tougher penalties and more court-ordered counseling for batterers.

Though it can be difficult to pinpoint exactly who worked behind closed doors to scuttle this year’s reform effort, some key opponents are well-known.

Republican Sen. Lee Bright of Spartanburg is a fervent defender of gun rights, and he is suspicious of many of the proposals that included provisions to restrict access to firearms. Bright, a member of the powerful Senate Judiciary Committee where five of the bills died this year, said many of the proponents of stiffer domestic violence laws use them as a cover for restricting guns.

“There’s a segment of our population that wants to take our gun rights,” said Bright, who raffled off an AR-15 rifle this year as part of a bid for U.S. Senate.

In the Senate in particular, such sentiment can be fatal to a bill’s chances because all it takes to basically stop a measure is one senator’s opposition.

Republican Sen. Larry Martin of Pickens, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, had no explanation for what happened to the bills that died in his committee. But he said his panel has tackled meaningful domestic measures in years past and generally stands behind efforts to protect women.

“We passed some good things that I believe made a real difference but we still have a long way to go,” Martin said.

House Minority Leader Rep. J. Todd Rutherford of Columbia also doesn’t hesitate to voice his dislike of virtually all of the bills designed to strengthen the state’s domestic violence laws. Rutherford, a criminal defense attorney in Columbia and a former prosecutor, is a member of the House Judiciary Committee, where seven of the domestic violence bills died.

Rutherford blames victim advocates for poisoning the well. He said all they do is push for laws that make it harder for the accused to get out of jail on bond and easier to increase their time behind bars once convicted of abuse.

He said such laws fail to take into account that many cases involve families that might be preserved if the abusers were given more options to avoid higher bonds, stiffer fines and convictions.

The current maximum 30-day jail sentence for first-offense criminal domestic violence might not seem like much to some, Rutherford said, but it’s a long time for most people to be locked up. If jailed, the man could lose his family, his job, his benefits and his house, he said.

Rutherford contends that’s why so many women want to drop the charges after they call police: They realize the destructive consequences for the whole family.

Rutherford wants more pretrial diversion, counseling and classes to help change behavior, reaching not only perpetrators but also young people who might otherwise become perpetrators.

“We’ve got to show them a different way. We truly need to take a comprehensive look at how to fix the problem ... all we do is lock people up,” he said.

But don’t expect him to propose such a bill, Rutherford said, because his political opponents will accuse him of “pandering to offenders.”

Besides, he said, “It’s an exercise in futility because that takes money and we’re not going to spend it.”

Republican Rep. Greg Delleney of Chester, chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, did not return phone calls from the newspaper.

Republican Sen. Tom Corbin thinks that domestic violence legislation has focused on the wrong things. It needs to focus on what causes violence. “There needs to be a lot more love for Jesus in the world, and I think that would curb a lot of violence.”

Focus on the causes

Between the end of March and the conclusion of the legislative session in June, six more domestic killings made headlines across the state.

Among those to die was 55-year-old Mariann Eileen O’Shields. She had checked herself and her daughter into a domestic violence shelter in Spartanburg and filed for a court order of protection to keep her husband away.

On April 30, she walked her 8-year-old daughter to the bus stop, not far from the SAFE Homes shelter where they were hiding. After her daughter boarded the bus to school, O’Shields walked back toward the shelter, less than 200 yards away.

A white van pulled near her. Gunshots shattered the quiet. She fell to the ground with three bullet wounds and died in an operating room. Her estranged husband, Robert Lee O’Shields, 52, awaits trial on a murder charge.

Republican Sen. Tom Corbin represents Greenville and Spartanburg in the Legislature. He also is a member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, where he opposed domestic violence bills with provisions to restrict firearms.

Corbin likened his feelings about gun restrictions to an episode of the 1970s television comedy “All in the Family.”

In the episode, he said, “Gloria is talking about gun control and how people were killed by guns and Archie said, ‘Would you feel better if they got pushed out the window?’ ”

Domestic abusers can turn to other weapons, such as knives or rocks or sticks, to get the end result they’re seeking: murder. Restricting guns won’t help solve that, Corbin said.

“A lot of times we’re not focused on the right thing. We need to focus on what causes violence and try to stop that,” Corbin said. “There needs to be a lot more love for Jesus in the world, and I think that would curb a lot of violence.”

By the time the legislative session ended in June, all but one of the domestic violence bills had died in committee.

The lone exception: a measure approved by the Legislature in early June and signed into law by Gov. Nikki Haley. It provides for court-ordered protection for the pets of the victims of domestic violence.

Sellers, the Democratic House member from Denmark, said the Legislature’s failure to pass any of the bills to protect domestic abuse victims, yet pass one to protect their pets, offers a sad commentary.

“When you say it like that, it’s laughable. Then you have to stop and say, ‘You know it’s not funny.’ A woman dying: It supersedes all politics, but it apparently doesn’t supersede ignorance.”

Jenna Henson Black, right, is overcome with emotion and is comforted by Safe Harbor Executive Director Becky Callaham during the opening of the new Oconee County women's Shelter. Black has been raising money for the shelter since 2004 after she left her abusive husband of 18 years.

Jenna Henson Black, right, is overcome with emotion and is comforted by Safe Harbor Executive Director Becky Callaham during the opening of the new Oconee County women's Shelter. Black has been raising money for the shelter since 2004 after she left her abusive husband of 18 years.

PART THREE: Honor and Rage

Her arms windmill with passion as her country twang resounds from behind a lectern like the revival preacher she has, in many ways, become. She has dreamed of this moment for a decade since her husband of 18 years beat her for the last time.

Jenna Henson Black is here in the state’s western-most county on this steamy July morning to open Safe Harbor, a shelter for abused women and their children. She’s raised money for the Oconee County shelter since 2004 when her ex-husband slapped her until she thought her teeth were falling out.

She fled while he slept.

Black prays this new shelter will provide safety for other women trapped in destructive relationships that leave them beaten, bloodied and broken. But she knows how difficult it is to escape the hold of these perilous unions, despite their dysfunction and danger.

Part of the problem is rooted in the culture of South Carolina, where men have long dominated the halls of power, setting an agenda that clings to tradition and conservative Christian tenets about the subservient role of women.

This has bred a tolerance of domestic violence that has passed through so many generations, behind so many closed doors, that today South Carolina ranks No. 1 nationwide in the rate of men killing women.

Oconee County, where six people died in domestic killings within six months in 2012, embodies many of the cultural traits that have made South Carolina the most dangerous state in the nation for women. Unlike the state as a whole, which has done next to nothing, Oconee took the killings as a call to action, galvanizing law enforcement, religious leaders and residents to confront the problem.

Yet old ways die slowly in rural corners like Oconee County, where God and traditional family values have long forged the backbones of life. Here, deep notions linger about the hallowed institution of marriage and a woman’s place in the home.

“There is a belief that men are totally dominant and women are supposed to be in the bedroom and the kitchen,” Black says. Like many in the Bible Belt, she considered divorce a sin and a source of shame, despite the beatings she endured.

“You can die, but you can’t get divorced.”

Women as chattel

South Carolina has been a patriarchal society from its very inception, and women have long been relegated to a secondary status.

They lacked the right to serve on juries here until 1967, and the Palmetto State didn’t formally ratify the 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote until two years later. Women couldn’t file for divorce in South Carolina until 1949. Marital rape wasn’t criminalized until 1991.

Progress has been made, but the state still struggles with challenges that impede women’s ability to advance. Only seven states have higher rates of women living in poverty. Just two states have lower per capita incomes. And only eight have worse rates of high school graduation.

South Carolina now has its first female governor, but the state ranks 49th in the nation for the number of women elected to its legislature, according to the Center for American Women and Politics. And that’s an improvement. For the decade until 2012, it ranked dead last every year.

Against this backdrop, it’s easy to see why domestic violence hasn’t garnered more attention in the Statehouse. When legislation goes before the state Senate, a lone woman sits among the men casting votes.

Carol Sears Botsch, associate professor of political science at the University of South Carolina in Aiken, explored the role of women in South Carolina politics in a 2003 report. She found a male-dominated power structure that often failed to see problems from the perspective of women. As a result, public policies were rooted in traditional notions that “simply reinforced women’s subordinate status.”

Brian Rawl, a Charleston County magistrate who handles domestic violence cases, puts it more bluntly: “We’re transforming from a social acceptance of a woman being chattel.”

The late political scientist Daniel Elazar described South Carolina as the “most traditionalistic state in the union,” with a political culture geared toward preserving a status quo that often benefits the values and needs of the elite. It is a place that champions limited government and taxation, cherishes its Second Amendment gun rights and trumpets the values of personal liberty.

Most Southern states share this model. They also share a propensity for violence . Four of the 10 states with the most shameful rates of men killing women are in the South: Tennessee, West Virginia, Louisiana – and, at No. 1, South Carolina.

Too close to home

Nestled in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, with rolling hills, quaint small towns and a trio of crystal blue lakes, Oconee County looks like a place people might go to escape the perils of modern society.

Drawing its name from a Cherokee word meaning “land beside the water,” Oconee is home to wild rivers and cascading waterfalls. It’s a picturesque place that bears the nickname “South Carolina’s Golden Corner.”

But Mike Crenshaw, the county’s sheriff, has seen a darker side as well.

In 2012, the year before Crenshaw took office, six county residents died in a trio of domestic killings. A 70-year-old Walhalla man fatally shot his wife on his July birthday, and then turned the gun on himself. A day later, a 34-year-old Westminster man committed suicide after gunning down his 11-year-old stepdaughter and critically wounding his wife. Four months after that, an 86-year-old Westminster man beat and stabbed his girlfriend to death, then killed the woman’s grandniece.

Crenshaw, then a sheriff’s deputy, questioned why law enforcement didn’t do more to stop the bloodshed. He made the issue part of his campaign for sheriff, vowing to do more. Then, five days after he took office in January 2013, a 58-year-old Seneca woman was shot to death by her live-in boyfriend, who later committed suicide. The bloody scene shook Crenshaw to the core.

“I left that morning feeling helpless because with all of these cases, there was no call history to law enforcement at all. We had not been aware of any problems within those families,” he says. “It got me thinking that we have to get to these folks somehow. It made me realize this is not just a law enforcement issue: it’s a community issue.”

But getting people to talk about the issue can prove a challenge in itself.

It’s not easy to overcome a culture of abuse that became “somewhat of an accepted behavior” in South Carolina, Crenshaw says. “It’s going to take some time to change that mindset.”

‘Back into a burning house’

Family violence has long lingered in the shadows in Oconee — and across South Carolina. That’s because it’s largely been viewed as a family issue, something to be dealt with in the home.

“The culture does not see domestic violence as a public health issue, which is what it really is,” says Mindi Spencer, an assistant professor of Southern Studies and Public Health at the University of South Carolina in Columbia.

Ninth Circuit Solicitor Scarlett Wilson, who oversees prosecutions in Charleston and Berkeley counties, agrees: “Even if we had unlimited shelters all over the place, I think culturally we don’t offer that support to victims. Nobody wants to hear about it.”

Crenshaw and representatives from Greenville-based Safe Harbor, which runs the new Oconee shelter, set out to break through that reticence. They met with community leaders, business people and representatives from the schools. They sat down with judges to push for stricter sentences for domestic violence, a crime that had been treated like “a traffic ticket, just a slap on the wrist.”

They also talked with clergy to challenge age-old beliefs that domestic unrest was best resolved in the home – an approach that many times made the situation worse.

“The ministers told us, ‘It’s really a family issue. They need to work that out,’ ” Crenshaw says. “But in some cases that’s like telling a victim to go running back into a burning house.”

What pastors communicate to their flocks also can fuel the problem, if inadvertently: Scripture says women are to be submissive. Suffering is part of life, as Jesus suffered for your sins, on the path to salvation. Divorce is a sin.

The Rev. Mark Bagwell of Golden Corner Church, a contemporary Baptist church in Walhalla, admits that churches have “not always been a place of refuge” for domestic violence victims. Grace Beahm/Staff

The Rev. Mark Bagwell of Golden Corner, a contemporary Baptist church in Oconee’s small town of Walhalla, concedes that religious vows and teachings have likely kept a good number of women from leaving their abusers. Churches have played a major role in making women feel that “God would be disappointed in them if they left their husband,” he says.

“The church has not always been a place of refuge.”

Turning a blind eye

Oconee County is certainly not alone in dealing with that issue. A few years ago, when community activist Marlvis “Butch” Kennedy first tried to train Charleston-area pastors about domestic violence, he’d hear things like: “That doesn’t happen in my church.”

“The church believes marriage is a godly institution. Nothing should come between a man and wife,” Kennedy says. “It’s a very slippery slope.”

In churches that did acknowledge abuse, Kennedy says, pastors often compounded the problem by counseling abusers and victims together – and then sending them home with the sting of their shared grievances still fresh. Back behind closed doors, the abuser would take out his frustrations on his partner all over again.

Today, pastors seem far more receptive to training from a local group he founded, Real MAD (Real Men Against Domestic Violence/Abuse). “The mentality is changing over time,” Kennedy says.

Bagwell agrees. He now takes a broader view of the dynamics involved in domestic violence and warns others of the potential dangers. He’s seen other pastors do the same.

“I’m grateful that ‘till death do us part’ is changing,” he says.

How far this awakening has spread is open to debate. A nationwide survey conducted this summer by LifeWay Research found that 42 percent of pastors never or rarely speak about domestic violence. Less than a quarter speak about the issue once a year.

Among pastors who do preach about it? Only 25 percent say it’s a problem in their own pews .

Answering prayers

Before escaping her husband, long before the opening of the new Oconee County women’s shelter, Jenna Henson Black prayed to God that her husband would change.

For 18 years, she prayed he would stop beating her.

She was praying for the wrong thing.

“It didn’t work. But it taught me that God will provide a way to escape,” she says. “God didn’t change him. He changed me.”

In the 10 years since she fled, Black has remarried and become a minister with her second husband at Grace Family, a non-denominational Protestant church in Seneca.

Now 66, Black realizes the problem wasn’t God or faith or commitment to her marriage. The problem was her ex-husband.

“I had a commitment to marriage, for better or worse, ‘till death do us part,’ ” Black says. “But when the death part came too close, I knew the Lord didn’t want me to be killed by my husband.”

PART FOUR: ‘I just remember the fear’

For 13 years, Therese D’Encarnacao stayed with her husband through the biting insults and accusations: You’re fat. You’re ugly. Nobody else will want you. She stayed through the times he hit her. She stayed through his chronic health problems and depression and unemployment.

She stayed until the day Keith Eddinger walked into their long, narrow master bathroom and pointed a gun at her head. He calmly shot her between the eyes. Then he killed himself.

At first, Keith was a gentleman, a welder who shared her love of fishing and camping. He took an interest in her young son. And an interest in her.

Fresh from a failed marriage to her high school sweetheart, Therese desperately wanted someone to love her. So for 13 years, she endured the abuse, partly out of hope, largely out of fear.

When she finally told her husband she wanted out, Keith got his gun.

Very real fear

Why do women stay in — and return to — abusive relationships, even until their deaths?

The question is central to helping them.

And the fact that women do stay so often provides a convenient excuse to blame victims rather than the men who pull triggers (or knives or fists). A lack of understanding prompts many, lawmakers included, to turn their backs on the pervasive, deadly problem.

It’s not a simple question to answer.

Experts and survivors both describe an all-ensnaring web of hope, culture, dependence, fear, religion and even love that binds women to their abusers. But mostly it comes down to what he controls — which often is everything, even her life.

The late state Rep. John Graham Altman sparked a furor in 2005 when he told a reporter that domestic violence victims are at fault if they return to their abusers.

He had just been asked why the House Judiciary Committee wanted to make cockfighting a felony but tabled a bill that would have done the same for domestic violence.

“The woman ought to not be around the man,” Altman said. “I mean you women want it one way and not another. Women want to punish the men, and I do not understand why women continue to go back around men who abuse them. And I’ve asked women that and they all tell me the same answer, ‘John Graham, you don’t understand.’ And I say, ‘You’re right, I don’t understand.’”

He’s not alone.

Many people don’t realize that when a woman tries to leave, or press charges, she is in the most danger she will face.

For 25 years, Elmire Raven, a domestic violence survivor herself, has led the charge at Charleston’s shelter for abused women, My Sister’s House.

The shelter includes this warning on its website: “The most dangerous time for a victim is when leaving the relationship. Fifty percent of injuries and 75 percent of domestic homicides occur after the relationship ends.”

“It’s a very real fear,” Raven said.

That day in 2010, when Keith got his gun and shot her, Therese had just told him she wanted a divorce. Keith didn’t want anyone else to have her.

After he fired a bullet into his wife’s head, Keith walked a few feet away and took his life. Little could he know that Therese would survive.

Elmire Raven, an ex-cop who was a victim of domestic violence, has run My Sister’s House, a shelter for women and children, for 25 years. She says women need to get out of abusive relationships. She did after the first time her ex-boyfriend slugged her in a rage over control and jealousy. Grace Beahm/Staff

Cultivating fear

The first time Keith became violent, he slapped her with an open palm, damaging her ear drum. Her son, then about 9 years old, was in the house.

Another time, he punched her in the stomach. She was pregnant and, later, miscarried.

After that, she called her first husband, with whom she remained friends, to come get their son and keep him safe. He offered to take Therese with him, too, until she could find her own place.

Therese stayed.

While many abused women stay out of fear of violence, Therese’s fear drew from a different well. Hers was a deep and unrelenting fear of being alone, fear of what Keith threatened: Nobody will want you but me.

Raised Catholic, she also was devoted to preserving her vows.

For better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and health…

Early in their marriage, Keith nearly died from a respiratory disorder. He suffered arthritis and spent long spells not working, in pain and depressed.

Early in their marriage, Keith nearly died from a respiratory disorder. He suffered arthritis and spent long spells not working, in pain and depressed.

And Therese was a nurse, not someone who abandoned the sick. She wanted to help Keith heal and return to the man she loved.

But as he got sicker, the psychological abuse and control grew more intense, the violence replaced by a barrage of insults, demands and suspicions. A friend urged: “You’ve got to leave him. He’s making you crazy.”

And she did leave, multiples times.

But Keith had this way of badgering, of cajoling and promising, until she returned.

In 2006, she moved out and lived in another state. After avoiding him for six months, he found her number. She answered the phone.

“I should have hung up on him. But I didn’t,” she recalled. “He had done a lot of changing again, and I did let him come back. I did love him.”

Besides, to hear Keith tell it, without him she would remain alone and unwanted forever.

“I just remember the fear. It’s always an abuser’s main weapon – fear,” she said. “They beat you down so much verbally that you lose yourself. It’s toxic.”

Other women fear becoming homeless, lost to the streets with their children in tow.

Only 35 percent of victims arriving at My Sister’s House have jobs. “They are in survival mode,” Raven said.

It’s especially tough for stay-at-home moms with limited workplace skills and no independent income, said Alison Piepmeier, director of the College of Charleston’s Women’s and Gender Study Program.

“There’s not even a choice. There’s no way out,” Piepmeier said.

Love, absolutely

Survivors often describe falling in love with charming men whose abuse began well into their relationships. Therein lies the hope. If only that man would come back.

Raven has seen it over and over: “Love, absolutely.”

Instead, many victims find themselves stuck in cycles of building tension — over dinners not prepared right, homes not cleaned just right, bills not paid, mouths not kept shut — much like a rubber band stretching and tightening with every sidestepped conflict. Until it snaps.

After the violence comes the so-called “honeymoon phase,” a time when he goes back to being the man she loves.

The seesaw of violence and passion “is like a Harlequin romance on steroids,” said Patricia Warner, project manager of the Domestic Violence Homicide Prevention Initiative at MUSC’s National Crime Victims Center.

The woman thinks: “It’s over now. He says he loves me and he’ll not do it again,” said Warner, who also directs the Tri-County Domestic Violence Coordinating Council.

Yet, Mr. Hyde still lurks.

.jpg) Therese D'Encarnacao, shows a video about her life and marriage to inmates at the Charleston County Detention Center who are part of the Turning Leaf Project during a lesson on domestic violence.

Therese D'Encarnacao, shows a video about her life and marriage to inmates at the Charleston County Detention Center who are part of the Turning Leaf Project during a lesson on domestic violence.

Verbal beat-downs

As Keith’s health worsened, the abuse and control worsened, too, especially behind closed doors. He became obsessed with the belief Therese was cheating on him.

“As he lost control over his life, he tried to take control of mine,” Therese recalled. “He was a master manipulator.”

A chatty and outgoing woman, Therese recalled increasingly harsh “verbal beat-downs.”

Once, Keith was a patient on her hospital floor. When she arrived at work one day, he accused her of sleeping with someone while she was gone.

He demanded she pull down her pants so he could check. She complied, caught up as she’d become in the insanity, the insecurity of his abuse.

Searching for a way out

In 2010, Keith had just come home from visiting his family in Arkansas. With him gone, Therese’s days in their North Charleston home had turned peaceful and quiet.

She realized what life could be like without him.

“It was like being tortured 24/7. I couldn’t live that way anymore,” she said.

She told him she was done. She wanted a divorce.

As usual, he chased her around the house, launching a tirade of pleas and insults. Stressed, Therese finally sank into a hot bath to relax.

Before she faced him again, she got out, dried off and sat down on the toilet of their master bathroom.

She didn’t know her husband had a new handgun.

When Keith walked in, she turned to him. “If I can’t have you, nobody can,” he said calmly. From about 5 feet away, she watched him fire.

Victim, survivor

Of females killed with a firearm, almost two-thirds are killed by their intimate partners. Therese nearly joined that Violence Policy Center statistic.

Of females killed with a firearm, almost two-thirds are killed by their intimate partners. Therese nearly joined that Violence Policy Center statistic.

But as Keith walked a few feet away, shot himself and died, Therese fought to live.

She spent three weeks in the hospital and remains blind in one eye. The bullet penetrated a facial nerve and damaged her inner ear. She lost hearing and suffers excruciating migraines. Now 48, her short-term memory isn’t great. She wears dark glasses and a hearing aid.

“There is a .25-caliber bullet in back of my brain, courtesy of him,” she said.

But Therese also is a survivor.

She survived to become a grandma and to realize the peace of independence. Today, she shares her story with other women and even jail inmates to prevent the ceaseless tally of deaths from domestic violence, to encourage abused women to escape before it’s too late.

North Charleston police officer Adrian Besancon takes a man into custody in early June after his live-in girlfriend accused him of assaulting her. The charge was later dismissed after the woman opted not to testify against him.

North Charleston police officer Adrian Besancon takes a man into custody in early June after his live-in girlfriend accused him of assaulting her. The charge was later dismissed after the woman opted not to testify against him.

PART FIVE : Cases fall apart, abusers go free

A young woman cowers in the passenger seat of a banged-up Cadillac, blood oozing from scratches carved in her face.

She weeps as a North Charleston police officer escorts her boyfriend in handcuffs from a nearby bungalow. Barefoot, with jeans sagging off his slender frame, the boyfriend glowers when asked how his girlfriend was injured.

“We fighting,” he answers with a shrug.

Police charge the boyfriend with criminal domestic violence, but he doesn’t spend long behind bars. He posts bail within hours and is released. Then, the charge goes away entirely after his girlfriend has second thoughts about testifying.

It’s a familiar tale across South Carolina. Cases against domestic abusers fall apart on a regular basis, allowing them to escape punishment and continue to mistreat the women in their lives — at times, with deadly results. Examples are easy to find.

Nathaniel Beeks, a 47-year-old Greenville County man, was arrested seven times for criminal domestic violence before he strangled his girlfriend to death in April 2011. Derrick Anderson, 34, of Greenwood, had six arrests for domestic violence and eight more for assault before he throttled the life from his ex-girlfriend in 2007.

A number of factors contribute to this problem, from overcrowded court dockets and under-trained police to victims too scared to testify against the men who beat them. Couple these issues with a domestic violence law that treats first-time offenders about the same as shoplifters and litterbugs, and it’s easy to see why abusers go free time and again.

After a 2001 study revealed that more than half of South Carolina’s most serious domestic violence cases never went to trial, then-Attorney General Charlie Condon ordered prosecutors across the state to pursue convictions even when victims refused to cooperate. That policy has continued under each of Condon’s two successors. They’ve also sent in outside attorneys to help prosecute domestic violence in struggling counties with few resources.

Yet 13 years later, state court statistics show similar results: Since July 2012, more than 40 percent of the 8,884 domestic violence cases handled in General Sessions courts were dismissed for one reason or another, according to a Post and Courier analysis.

The state doesn’t track the outcome of charges in magistrate and municipal courts, though they handle the lion’s share of domestic violence cases. One state commission sampling found that more than half of the 5,329 domestic violence cases that landed in magistrate courts between July 2012 and June 2013 were ultimately dismissed.

A Post and Courier analysis of local court data found similar patterns. About six in 10 domestic violence cases that ended up in Charleston and North Charleston municipal courts between 2009 and 2013 were dismissed or dropped by prosecutors. In suburban Mount Pleasant, the figure was around 38 percent.

North Charleston police officer Adrian Besancon responds to several domestic violence calls on a weekly basis. “It’s one of the most dangerous calls you can go on," he says. Grace Beahm/Staff

Cold feet

Prosecutors say a percentage of these cases were thrown out — about 9 percent in Charleston, for example — when the abuser successfully completed a court-ordered counseling program for batterers. The numbers also don’t reflect when a suspect agreed to plead guilty to a charge other than domestic violence, such as simple assault.

But prosecutors acknowledge that a sizable number of cases simply go away for lack of evidence or because the victims back out of testifying.

“Our biggest issue is the lack of cooperation from victims,” 9th Circuit Solicitor Scarlett Wilson said.

Though frustrating, she understands that reticence, as do the police investigating these cases. North Charleston Detective Chris Ross, a 36-year veteran, said battered women often return to their abusers and seek to have charges dropped, either out of love, necessity or fear.

“A lot of them are terrified,” he said. “They are afraid they will face additional retribution, which is a legitimate concern.”

Charleston County Magistrate Brian Rawl said the horror of the whole situation is that these women often have been brutalized for years. Studies show that victims often are assaulted seven times or more before reporting. Some never do.

The 29-year veteran judge recalled the case of an 84-year-old woman who accused her husband of beating her. Rawl asked the woman how long she’d been abused. She replied “our entire 60-year marriage. I have bone cancer now and I can’t have him beat on me.”

Pressing on

S.C. Attorney General Alan Wilson pushes prosecutors to move forward with domestic abuse cases even when victims feel too embarrassed or afraid to cooperate. He tells victims: “This is not your cross to bear. This is my burden. ... He has committed a crime against the state.”

Still, it’s an uphill climb.

A “victim-less” prosecution can succeed if an officer witnesses the assault or can find fingerprints, a recording or some other evidence to tie the abuser to the crime. But domestic violence generally takes place within the home and out of sight, with no witnesses but the abuser and his victim. To make a case stick, it usually comes down to the woman testifying against her man.

The dilemma is plain to see in one Friday morning court session in Charleston. A case is dropped after the suspect shows up holding the hand of the girlfriend he’s accused of beating. She tells the prosecutor she just wants the case to go away. Another man soon steps forward with his phone in hand to proffer a text message from the mother of his child. She also has had a change of heart about going forward with charges.

A third man, who has out-of-state convictions for beating women, has his case continued after the girlfriend he is accused of assaulting doesn’t show up for court. When asked where she is, he just scowls and shrugs.

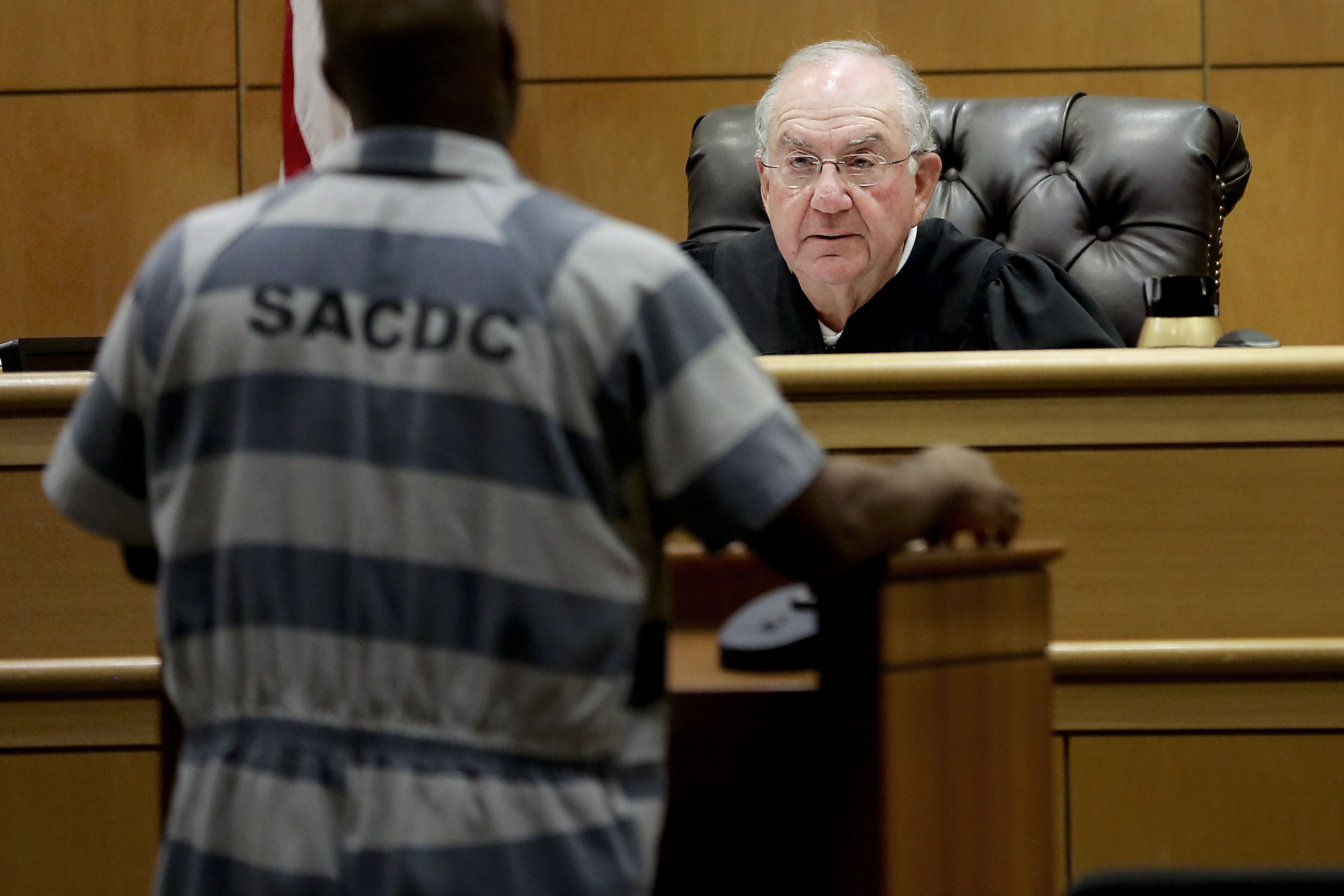

Municipal Judge Joe Mendelsohn presides over the Criminal Domestic Violence court in Charleston in August. Here and in similar courts across the state, winning a conviction often takes a woman having the courage to testify against her man.

Scant resources

Keep in mind that Charleston is one of the better-equipped cities in the state, with its own designated domestic violence court and a special victims unit with five investigators and three victim advocates. That’s larger than the entire force for 127 police agencies across the state.

In many smaller departments, domestic violence cases are just part of the regular mix for officers. In cities and towns that can’t afford prosecutors, these officers are tasked with presenting the case in court as well.

The state’s Criminal Justice Academy in Columbia has boosted training in recent years for front-line officers in the legal and behavioral aspects of domestic violence. Instructors even use role-playing to help cadets understand how batterers intimidate, isolate and manipulate their victims.

Even with this increased focus on the topic, problems remain.

A year-long study of Charleston County domestic violence incidents, published in 2010, found gaps in documenting key evidence on incident reports.

Officers were left to their own discretion to note when a victim had been strangled — a major indicator of escalating violence. When noted, more than 60 percent of officers used the wrong terminology to describe what happened, potentially hampering prosecutions.

Most of the reports failed to document any past violence against the victim or previous charges against the abuser. Police also seldom lodged additional charges against offenders who exposed children to violence. Just seven of the 315 incidents where children were present resulted in an additional charge of child endangerment, the study found.

“The person taking the physical blows isn’t the only victim,” Wilson, the solicitor, said. “There are also the children, and we see the effects of that.”

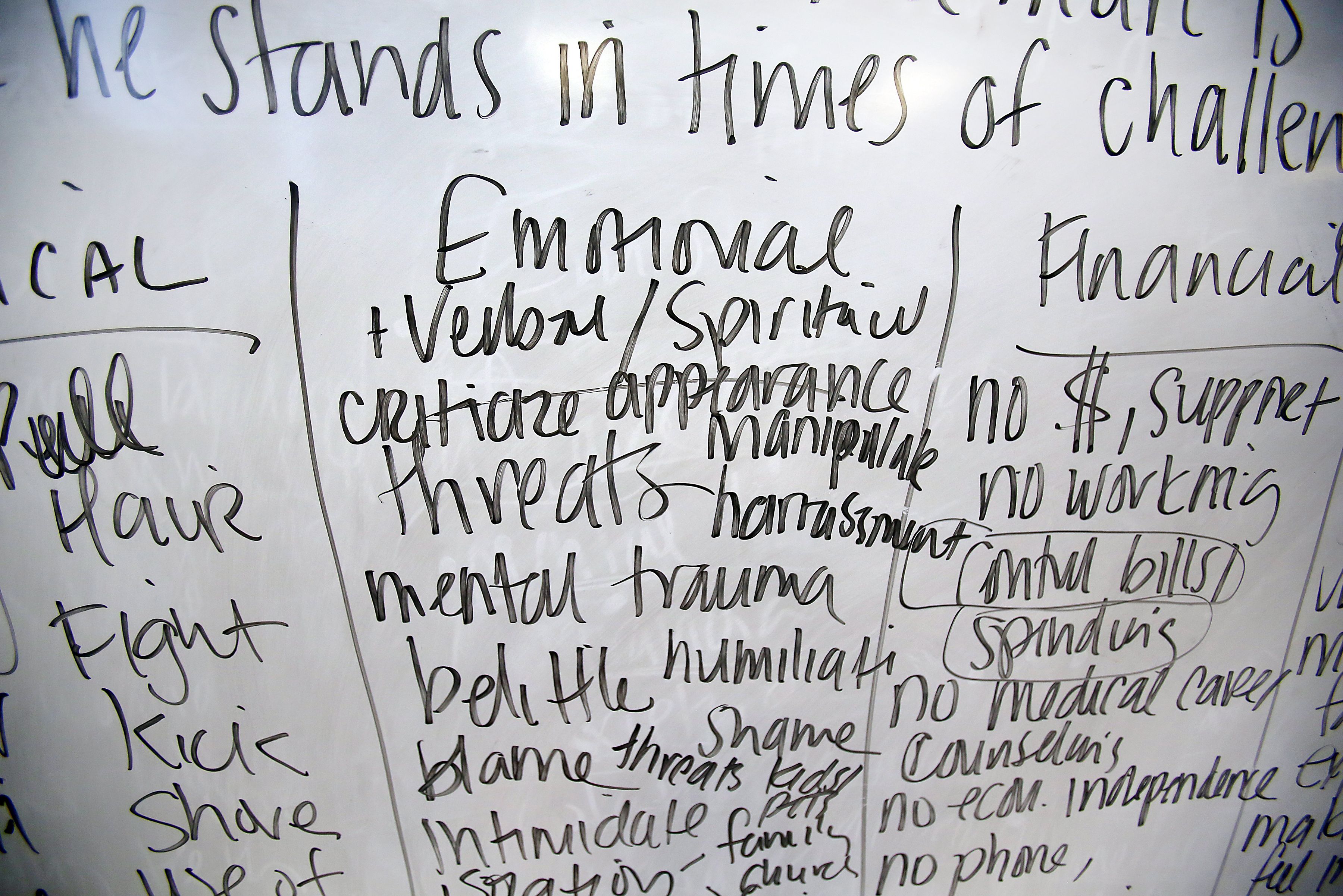

A list of abuses that can be inflicted by a partner in the case of domestic violence were compiled by inmates participating in the Turining Leaf Program.

PART SIX: No more missed opportunities

Teacora Thomas did everything she could think of to protect herself from her estranged husband, who had beaten her bloody in an obsessive campaign to do her harm.

She changed the locks on her Richland County home. She armed herself with pepper spray and a stun gun. She filed charges against him after body blows and a kick to the head put her in the hospital. And she got a court order barring him from making any attempts to contact her.

None of this made a difference on the morning of Oct. 15, 2012, when Thomas returned home with her mother to gather belongings so she could move away. Dexter Boulware lay in wait for her in a closet. He had broken in while she was gone.

“You all going to die today,” he hissed, leaping from his hiding place, a pistol gripped in his hand.

She tried to escape, but Boulware grabbed his wife, aimed the gun at her and made good on his promise. She died before reaching a hospital.

Thomas’ case illustrates the problem with South Carolina’s fractured approach to dealing with domestic violence. A number of people, from police to social workers, have a hand in protecting women from abuse, but a lack of resources, communication and coordination leave dangerous gaps in the web of support.

Police arrest abusers. Magistrates set bail. Doctors tend to wounds. Counselors shelter victims. Judges issue restraining orders. Prosecutors prepare for trial. But often, these players work independently from one another, passing the baton back and forth without sharing information, assessing potential risks and working on collaborative solutions.

This failure of communication helps explain why South Carolina leads the nation when it comes to the rate of women killed by men.

Two years after Teacora Thomas’ death, Richland County Sheriff Leon Lott acknowledged that she took almost every step available to protect herself. But as for his department, he said, “I don’t know if we could have done anything differently.”

Therein lies the problem: Even in an urban county such as Richland, which boasts one of the state’s better law enforcement operations, the missed opportunities to save Thomas were numerous.

Boulware’s increasing violence toward Thomas triggered no special response from deputies or court officials, even after he beat her so ferociously that she ended up in a hospital. No one took the time to evaluate the danger he presented. Once he was arrested for that assault, a judge let him go almost immediately on a personal promise to appear for his court hearing. She obtained a protective order, but no special efforts were made to keep tabs on Boulware until he left threatening messages on her phone the day before her murder.

Thomas was left to save herself at a time when she was most vulnerable.

Jacquelyn Campbell, a Johns Hopkins University professor who is one of the nation’s leading experts on domestic violence, said Thomas’ case illustrates a complete failure in the fight against domestic violence.

“If there was a community-wide strategy to address high-risk domestic violence cases, there are several things that could have been done,” she said. “Everyone has to get on board. It has to be a coordinated response.”

Richland County clearly is not alone in this plight. Examples abound of similar tragedies across the state.

There was Cindy Koon, who was beaten, strangled and stabbed, allegedly by her husband, in 2012 following a three-year stretch in which Newberry County deputies had been called to the couple’s Prosperity home 24 times for domestic disputes. Or 46-year-old Donna Parker, blasted with a shotgun in a North Myrtle Beach parking lot in 2008 after seeking a restraining order and calling police on her estranged husband a dozen times in a two-month period. Or Susann Burriss, 51, who was left to fend for herself in Anderson after her estranged husband beat her with a baseball bat in 2008. He then returned home three months later and killed her with a shotgun, stuffing her body in a trash bin, where she bled to death.

In each case, and many others like them, warning signs were clear, but the victims were ultimately left to their own devices.

A better way

That’s not the way it should be, or has to be, based on the experience of other states employing far more aggressive approaches to curbing domestic violence.

In Maryland and several Massachusetts communities, police, prosecutors, domestic advocates and probation officers work in teams to identify high-risk domestic violence cases, share information and rapidly connect abused women with services to help them escape harm.

The teams employ numerous techniques to calm the situation and alter the dynamics at play, including placing the abuser under surveillance, removing guns from his home and getting him counseling.

The Massachusetts effort, spearheaded by the Jeanne Geiger Crisis Center in the small coastal city of Newburyport, got its start after the 2002 murder of resident Dorothy Giunta-Cotter, who died trying to escape a husband who had abused her for two decades.

After years of enduring beatings and threats, fleeing to shelters and getting restraining orders, she took a stand, returned to her home and got an order of protection. He broke in anyway, held her hostage and shot her dead.

As counselors and authorities sorted through the events that led to her death, they came up with a strategy aimed at shifting the onus for protection away from victims. Instead, offenders are held more accountable for their behavior. The strategy includes using GPS technology to track the offender’s movements, making sure he doesn’t go near the victim. It also includes “preventative detention” to hold high-risk offenders without bail until trial.

This creates a cooling-off period in which a victim can get help without being in imminent danger. And she can do so without having to uproot her life and seek sanctuary in a shelter, said Kelly Dunne, operations chief for the Geiger Center.

“Going to a shelter literally means ripping them from their jobs, forcing them to pull their kids out of school and going to a community they may never have been to — and they have to do this sight unseen,” Dunne said. “It always seems so unfair what we are asking these women to do. They were the victims of a crime, yet they are the ones whose lives have to be completely disrupted.”

Maryland’s system went statewide in 2003 and reports a relatively steady decline in domestic killings since that time, dropping from about 70 to 80 each year to between 40 and 50.

The Massachusetts group has intervened in 129 cases in the greater Newburyport area since 2005 with not a single killing occurring among the women it served. Another 25 high-risk teams have been created across the Bay State to replicate this strategy in their communities.

Last year, the U.S. Justice Department awarded a $2.3 million grant to help the two groups train others in their methods, and North Charleston is among 12 communities under consideration to get that help.

South Carolina’s third largest city, has led Charleston County in domestic violence incidents in recent years. It is participating in a year-long review to determine ways it could improve its response to the problem, whether through better reporting of crimes, reforming the court process or holding offenders more accountable. Six cities will eventually be chosen to receive additional training and aid in putting those plans into action.

The Lexington County Sheriff’s Department in South Carolina’s Midlands has already implemented a system similar to those in Maryland and Massachusetts.

Lexington employs a special investigative unit that tracks domestic violence cases and coordinates prosecution, court action and services.

The Sheriff’s Department said the effort has been so successful that the county can go a year at a time without a domestic homicide. And it’s rare for any abused woman to be killed if the special unit has identified a problem and begun working with the couple, sheriff’s officials said.

The odds of murder

These programs are rooted in pioneering research that Campbell, the Johns Hopkins professor, conducted back in the 1980s. Her study showed domestic violence tends to follow predictable patterns as it intensifies toward a deadly conclusion.

Violence moved along a continuum, escalating from harsh words and threats to physical abuse. Acts such as choking proved to be key signs of a potentially lethal outcome. Campbell also determined that these women faced the greatest danger during times of change, when they tried to leave their abuser, got pregnant or started a new job. The threat was greatest during the first three months after the life change occurred but dropped dramatically after a year’s time.

These findings led Campbell to develop the “Danger Assessment Tool,” a 20-item checklist of risk factors that gauges a domestic violence victim’s likelihood of being murdered. Some of the risk factors include past death threats, an intimate partner’s employment status, and that person’s access to a gun.

“Victims need knowledge,” Campbell said, “and this shows them the danger they are in.”

The assessment can be used to persuade a victim to go to a shelter or seek other help. It enables police and counselors to know when to be extra watchful with both the victim and the abuser. It also provides prosecutors with an ability to know which abusers should be jailed or released only with strong restrictions.

In the Teacora Thomas case in Richland County, such an assessment might have prevented the killing from occurring, Campbell said.

“Teacora could have worked with a domestic violence agency to understand her danger better, using the Danger Assessment or some other tool to assess risk, and safety plan accordingly,” she said. “She should have been working with the police instead of her mother in gathering her belongings because evidence has shown that one of the most dangerous times for domestic abuse victims is when they take steps to leave the abuser.”

Deadly lessons

That lesson has been demonstrated many times in South Carolina. Last year in February, 34-year-old Kendra Nakeel Johnson was shot dead in Florence, her ex-boyfriend accused of killing her because he couldn’t deal with her leaving him. Five months later, Robert Hurl, 44, of Anderson was charged with killing his estranged wife when their marriage disintegrated. Then in December, 18-year-old Sierra Landry was shot dead in Lancaster about six months after a court told her estranged boyfriend to stay away from her. He’s now awaiting trial on a murder charge.

South Carolina’s Criminal Justice Academy teaches elements of the danger assessment to officers. It’s part of a retrenched focus on domestic violence that boosted training on the subject from four hours to 40 a few years back. Brian Bennett, a domestic violence instructor at the academy, said it’s important for officers to be keen observers and understand the warning signs that more violence may lay ahead.

“A lot happens with words, but once they start putting hands on intimate partners in an attempt to do harm, that shows the control most normal people have over their behavior is starting to be lost,” he said. “And for that to move to an even higher level is not that far off.”

Perhaps so, but few police departments around the state use the assessment. Some agencies contacted by The Post and Courier had never heard of the tool.

The Spartanburg Police Department is the only law enforcement agency in the state that has received formal training in use of the Lethality Assessment Program, an adaptation of Campbell’s research for use by police and other first responders. The Maryland Network Against Domestic Violence developed the program, which has been taught to police agencies in 32 states.

Spartanburg Police Capt. Regina Nowak said the department began using the program, with some local alterations, about a year ago to “give officers another tool in their belts.”

In the past, she said, officers often left the scene of domestic calls frustrated because the couple refused to cooperate when they arrived, or the woman was too afraid to press charges. With the assessment, she said, the officers can question the victim more effectively and help her see the danger she is in.

If the victim answers “yes” to any one of three critical questions, Nowak said, the officer immediately calls a 24-hour phone line staffed by a trained “lethality screener” who attempts to intervene to help the woman get to a shelter.

With this, Nowak said, officers get a chance to do something constructive, and the victim gets help.

Alicia Alvarez of Charleston displays her domestic violence ribbon tattoo that gives the date she left the man she was living with after he strangled her into unconsciousness.

In the secrecy of home

While these tactics have made a difference, they still don’t reach an untold number of women who endure beatings in the privacy of their homes and never tell anyone.

Women such as Alicia Alvarez.

She kept quiet for years about the verbal trashing, body blows and choke holds she received from the man she once lived with. It was embarrassing, shameful, too hurtful to share. That didn’t change until she saw something the last time he assaulted her.

As she slipped toward unconsciousness, his hands tightening around her neck, she caught a glimpse of her terrified 5-year-old son, trembling as he helplessly watched the attack.

Alvarez vowed that if she survived she would take her two children and run. Her last thought as she passed out: “I can’t let my kids see this.”

Shortly after she recovered, the Charleston woman told her abuser she was taking the kids on a shopping trip to Wal-Mart. She drove instead to a safe haven out of state and stayed away.

That was several years ago, and Alvarez and her children have since returned to the Charleston area. She’s happier now, but vividly recalls the “psychic hold” that made her stay with her abuser without ever reporting anything to police.

Now, Alvarez wants to reach out to other victims so they know they can get out. People also need to “be nosy” and pay attention to relatives, friends and neighbors because domestic abuse thrives in secret inside the home, she said.

Aside from scattered billboards and some proclamations during Domestic Violence Awareness Month in October, South Carolina has no comprehensive effort to reach silent victims. The state lacks a coordinated campaign to address a social epidemic the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calls “a serious, preventable public health problem that affects millions of Americans.”

Michaele Cohen, executive director of the Maryland Network Against Domestic Violence, contends that major outreach is necessary if a state is to make serious strides against domestic abuse. Her group runs a statewide campaign that includes taking brochures and other information to hospitals, clinics and salons. To reach these silent women, they emphasize some alternatives to seeking haven in a shelter, such as counseling, legal assistance, safety planning, a help hotline and follow-up visits.

“It’s hard to know how many people are saved,” Cohen said. But she said studies show that women who use domestic violence services are almost never the victim of murder or attempted murder.

Dunne, from Massachusetts, agreed: “I truly believe that many of these homicides that occur are preventable.”

The gravesite of Detra Rainey and her four children – William, Hakiem, Malachi and Samenia – in West Ashley. Rainey’s husband killed her and her children in a September 2006 shooting spree at the family’s North Charleston mobile home, authorities said.

PART SEVEN: Enough is enough

A chorus of voices that includes police, pastors and politicians, has condemned South Carolina’s grisly record of violence toward women. Their words, however, haven’t translated into much action.