Training for Danger in Mexico

As more news professionals die in Mexico's ongoing drug war, a look at how some are learning to protect themselves.

On July 29, Mexican radio journalist Juan Daniel Martínez Gil was found near the resort town of Acapulco, his hands and feet bound, his head wrapped in plastic, his body badly beaten and buried alive. The day before, the lead investigator of another journalist's murder was shot to death as he returned home from work.

It was a particularly frightening week to be a journalist in Mexico, a country where 27 journalists have been killed since 2000, but as the Committee to Protect Journalists noted in a special report in June, "even as the rate of killings ebbs and flows, self-censorship, skewed coverage, and manipulation of the news are constants." And so is their unstated corollary: psychological stress.

As Dart Center readers know, some journalists are at risk for long-term psychological problems, including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and substance abuse. It's a risk exacerbated not only by exposure to traumatic events, but also by a range of more preventable factors, from absence of social support to coping through avoidance. (See our research fact sheet for more on how reporting affects journalists.)

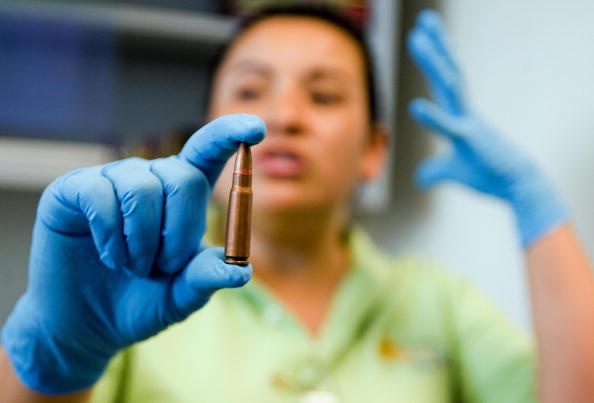

The toll of not only covering extreme violence, but also living under its threat, is rarely discussed. But, as video journalist Deborah Bonello has reported, it can be prepared for. Her multimedia reports on a five-day survival training put on by the Rory Peck Trust and Article 19 in Toluca, Mexico, provide a window into the training process — and also the desperate situation that makes such training necessary.

The 18 journalists first trained for physical threats: facing mock kidnapping, scaling steep hills covered in thorny bushes and improvising stretchers. Then they returned to the classroom for another new experience: sharing stories and getting concrete psychological training from Dr. Ana Zellhuber.

Bonello reports:

One of the four women on the course, a reporter from Tijuana, talked about the time she was approached by a man who said the Mexican Army had massacred people in his town. She didn’t know what to do because as the man told her his story she knew she was going to cry but she worried that crying would draw attention to herself.

“There are no wrong emotions,” said Zellhuber. “And there are always emotions.”

Over e-mail, Zellhuber described focusing on two kinds of techniques in her training: those to maintain resilience in the face of stress and traumatic events, and those to provide "psychological first aid" to assist the victims they interview.

I caught up with Bonello in the Mexico City office of the Los Angeles Times, where she works on contract as a multimedia reporter, and asked her to describe how these techniques were taught.

Bonello recalled a mix of activities and advice from both trainer and journalists. Zellhuber taught them breathing exercises and walked through role-playing various situations. She warned them never to put their lives at risk or make promises to victims they couldn't keep. A photographer offered that when he is in the midst of a riot, he takes himself out of the situation, closes his eyes and breathes on his own for a while.

"The journos were loving it," Bonello offered, "because [they] simply don't get much advice and guidance in these areas — from anyone."

As Zellhuber pointed out, in Mexico as elsewhere journalists rarely acknowledge, much less discuss in the open manner of her session, how their work affects them. Asked what Mexican journalists covering violence most lacked, she had one clear answer: "Knowledge and consciousness of the psychological, emotional, physical and social risks involved."

One possible solution — peer support and knowledge sharing — is a rarity. "There is more competition than solidarity amongst journos here," says Bonello, a problem compounded by low pay — Bonello cites a photographer paid $20 US for photos by a national newspaper — and low employer support.

Indeed, as Bonello reports, the incentives are just the opposite. "Where training is in short supply, wages are pitifully low and reporters aren't protected or helped by their employers, it's easy to see how they themselves can fall prey to corruption."

A more common survival mechanism is self-censorship, as an anonymous reporter for a newsweekly called Zeta in Tijuana relates in Bonello's video interview:

"I am a reporter, but not an investigative reporter ... We have the instruction not to investigate deeply into drug trafficking, that situation, because of the safety: because three editors of Zeta weekly newspaper have been murdered."

Even Zellhuber, a trainer who was prepared to face a prevalence of post-traumatic stress, was surprised by the desperation of the journalists' situation. "I understand now that they are a kind of thermometer of the amount of violence that our country is living," she wrote.

But a thermometer can only take so much heat.