Mission Accomplished: Photogs On Iraq

After covering Iraq, correspondent Michael Kamber felt the need to get out pictures and oral histories from colleagues that had not been seen or heard. Alan Chin, one of the photojournalists featured in the book, sat down with Kamber to discuss the making of Kamber's unique history of Iraq, Photojournalists On War.

By Alan Chin

The work of thirty-nine photographers, including myself, are accompanied by interviews Mike conducted over five years. Mike did not feature his own photographs or recollections in the book because he thought it would be too self-serving. He felt his role was to ask the questions and start the conversation. I am honored to be one of the participants that he sought out. But I wanted to know more about why and how he became motivated to create the project.

We met for lunch near the Bronx Documentary Center that Mike founded with Danielle Jackson in 2011. The following is a lightly edited transcript of the conversation. (Buy the book here.)

THE REAL WAR

THE REAL WAR

Alan Chin: I’m sure a lot of people have asked you this question before; could you talk about what gave you the idea for this book?

Michael Kamber: I wanted to do a book about censorship, and there were a few different issues I wanted it to address. One was I kept coming back from Iraq to an American population that seemed completely uninvolved in the war.

AC: How would you see that? What made that apparent?

MK: You could walk the streets and talk to people and watch the news, and there was almost no mention of the war. You didn’t see signs about the war, you didn’t see people protesting, you didn’t see people even supporting the war. Aside from an occasional bumper sticker, there was no evidence that we were even fighting a war.

AC: Even though for some of that time at least, in periods of big operations or high casualties, it would be all over the headlines.

MK: All over the headlines? No. By 2007, 2008, yes, there were some headlines about the “surge." There was definitely some press, but the coverage I did see didn’t seem to represent the war I knew. People seemed totally apathetic. Most of the pictures didn’t look like the war I had in front of my eyes.

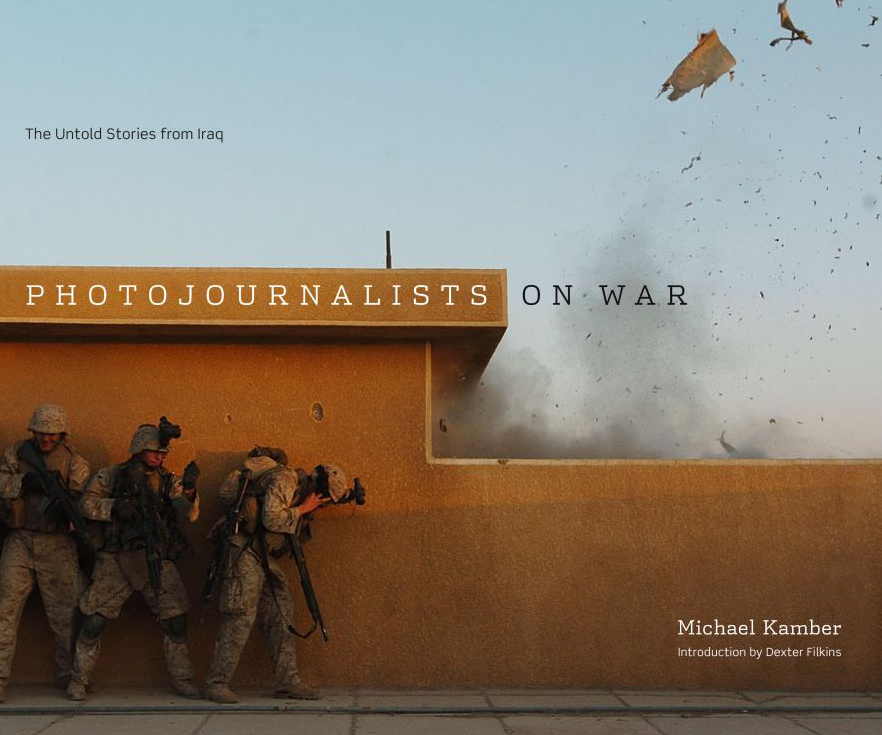

The slideshow images and text below are excerpted from Photojournalists on War: The Untold Stories from Iraq by Michael Kamber with an Introduction by Dexter Filkins. The book was published on May 15, 2013 by University of Texas Press. Scroll over the top of each image for captions and credits.

AC: Did you think that the coverage was too sanitized or too controlled?

MK: Yes, I thought it was too clean. If forty people were killed in a car bombing, you would see a headline that said “40 dead” but you wouldn’t see a picture of it. Rarely, rarely would you see pictures.

AC: Do you think that was because of censorship, either self-censorship or the censorship of the military, or is it something bigger in American society right now? Why do you think the war we were seeing in reality [in Iraq] was not at all the war that was seen here?

MK: It was a brutal, ugly, nasty, horrible war. With people torturing their neighbors to death with power drills. People massacring young children. It was more brutal than anything I could have imagined and that wasn’t the coverage I was seeing.

AC: But isn’t that always the case? You’ve covered lots of conflicts before, in Africa for example. Was there one personal moment when that hit you, or did it just build up over time?

MK: There was something special about this war. It was an accumulation of car bombings in public places that were killing children, things like that.

AC: The pure senselessness of it?

MK: Yes, a lot of it was that, and also, all wars are fought on the backs of civilians, but this one was all civilians. I would guess that 95% of the people who have died in the Iraq War were civilians.

AC: Because there were never that many insurgents to begin with, and the Americans were very protected, they got killed occasionally, but…

MK: There were no front lines. The Americans were dropping bombs from a distance; the insurgents were fighting amongst the population. When the Americans went in and got into a firefight, it was in the middle of somebody’s neighborhood. It was just all civilians all the time. That horrified me, and I didn’t see enough of that in the press.

AC: There’s a natural tendency in the press to always look for that front line, even when there isn’t one, to look for a “story.” Whereas in reality there wasn’t necessarily a “story," it was, as you’re saying, just this incredible level of violence.

MK: And it was just the most amorphous war I’ve ever seen. Even more so than the Liberian Civil War. Everybody was shape shifting. People were switching sides, merging into other groups; they were fighting their allies. It was a fantastically complex war, which is one of the reasons the American people didn’t get behind it or get against it or get involved in it because people just didn’t seem to understand it.

A New York Times reporter went to Capitol Hill in 2006 and asked if they understood the difference between Sunni and Shia and nobody on the Hill could figure out if Al-Qaeda was Sunni or Shia. That was on Capitol Hill among lawmakers who were passing legislation around the Iraq War. And they didn’t even understand the basics of the dynamic.

THIS IS HISTORY

AC: This whole time you were talking to your friends and colleagues – people like me and everyone in the book. At what point did you think, “I have to write this down, I have to record this.”

MK: I thought I was going to write a book about censorship. I was fighting constantly on embeds with military guys who were refusing to take me to the battle front. They wanted me to do stories about schools being painted and if I saw combat I was fighting with them about what photos I could publish, and I said, I want to do a book about censorship, so I started talking to Joao Silva and others and the book went off in different directions. People started telling me great stories. I’d been talking to Ashley Gilbertson, to Yuri Kosyrev. People had incredible stories. I thought, “This is history.“

And it’s not like I saw twenty great books out there that really encapsulated the history of the Iraq War. Actually, I saw almost none. Or at least not the war that I knew. I thought the New York Times, the Washington Post, and NPR did some great work. There’re plenty of people that did good reporting there, but that doesn’t mean that it’s captured in one place where people can go back and look at it.

MAKING THE BOOK

AC: When we look back at other wars, there were collections of images of WWII or Vietnam or to a lesser extent, Korea. But there doesn’t seem to be anything like that now. Why do you think that is? Is it because of this disconnect for the American people; that no one was interested in the way they were in past wars when it was a drafted army?

MK: I hate to say it; to some degree people aren’t interested in books that much any more. The difference between the Vietnam era when people wanted to have a picture book to hold in their hands, and today, 80% of the young people are clicking on the Internet.

They’re not going to go out and buy a book anyway. It’s just different; the death of the traditional media. The economics of doing books now: photographers are expected to show up with $20,000 in hand to get a publisher to print their book. It’s crazy. How does anybody do any books anymore?

I spent five years on this book. I just kept chipping away. I interviewed over seventy photographers and I put 39 in, so it was extremely difficult to leave out almost half the people I interviewed. A lot of them are friends. Some of them were not pleased about it.

AC: It’s really hard, creating a project like this. You said that the war was ignored, but isn’t it true that a lot of the images we saw were repetitive? Raids. People being handcuffed or in a hood. Helicopters. The MASH unit, because that’s where you can get access. There are maybe ten kinds of things that 80% of the pictures are of. How do you get around that?

MK: I dug through people’s archives. Even stuff people didn’t send me: I would Google their images and spend hours digging up stuff they hadn’t sent me, and say, “Hey, I want this.” People would say, “Oh, I forgot I took that.” I talked to their agencies. People will send you the same 10 images that they always use for a slideshow. You got to dig deeper and say, “Hey, I need more than this.” I had help. I had several assistants, like Nicole Schilit. She dug out thousands and thousands of photos. Photos that had never been published, photos that people forgot they even took.

AC: It must have been difficult to find a publisher?

MK: It wasn’t that hard, actually. I had one bad experience and then the University of Texas immediately wanted the book. They were very straight up.

AC: So you knew about them and brought the project to them?

MK: I got an agent, Sterling Lord Literistic, journalist Matt McAllister turned me on to Sterling, and they were surprisingly receptive. It was tough in the beginning because I heard again and again when I was trying to get an agent, “Is this a photo book or is this an oral history? Which is it?” And I said, “Both.” And they said, “It can’t be both. It has to be one or the other. How are we going to market this?”

AC: Why do you think they said that?

MK: You don’t see that many books out there that are half words and half photos. It’s usually 90% one, and 10% the other. It just is. A little bit of text and an introduction…

AC: It looks like a photo book, now, though…

MK: Yes, but its also got 150,000 words in it.

AC: The interviews are just long enough to pull you in and make you want to read the next one. The length: how did you work with that? I imagine people could talk for hours.

MK: Sometimes four hours.

AC: How were you able to cut them down? Why didn’t you do ten photographers, each one three times as long or all seventy photographers, each one half as long? What made you shape them into the pieces that you did, with 3-5 pictures roughly and however many words per photographer?

MK: It’s instinct. There was a certain point where we didn’t want to read 10,000 word interviews but we didn’t want to read 1,000 word interviews either and the middle point just felt right. I wanted to get in-depth but the book doesn’t have to be 800 pages! It’s the compromise I came up with in my head.

MILITARY FEEDBACK

AC: Who’s reading this book? Who’s buying this book?

MK: Of course photo people are buying it. I’m going to do a big push with academics in the fall. I don’t know if it’s on their radar yet. And actually some military folks are starting to read it. I got an email this morning from a woman. She said, “My daughter served in Iraq and I can’t get over this book. It’s fantastic but I’m not ready to show it. My daughter is just not ready for it.”

AC: But it’s her daughter who is the veteran.

MK: Yes, her daughter’s a vet. She’s the mother. She said, “I want to see it, I want to have it and I find it so powerful, but I’m not sure my daughter is ready to see it right now.“

AC: Do you think she’s someone who found it just from having done an Amazon search on Iraq?

M: I should ask her. There’s Colonel Dave Romine from Texas, he’s got a copy of the book. He wrote me a long glowing email, talking about his memories and his struggles and how the war runs together in this convoluted mish-mash, and that he’s found it tremendously valuable.

My publisher in Texas said, “The military’s not going to like this book.” But I disagree; because I don’t think the military wants propaganda. I think for a lot of the guys who were in Iraq, it was a horror show and I think they want something that honestly represents the war. It’s not an anti-war diatribe, but it is a good hard look at the war.

AC: I personally started out with more of an anti-war perspective than some, but by the end, would you say that many of the vets ended up, if not actually anti-war, certainly very critical of the way things were playing out?

MK: I was pro-war in the beginning. The first rule of war is chaos. The first thing you can plan on is to take your plan and throw it out the window. Because it isn’t going to go down the way you think. And I knew this, but I didn’t anticipate any of what happened in Iraq. I hadn’t worked in the Middle East, nor had Dick Cheney, nor had Donald Rumsfeld, and they sidelined the people who had.

It was extraordinary. There was a degree of incompetence that I saw in the way the war was handled, and I don’t mean by the soldiers on the ground. I mean higher up. I was watching stuff happen and just shaking my head.

AC: Do you think we were all naïve at the beginning, even if we didn’t agree with them, that they would be a little better at it?

MK: Yes. You’re going to invade a country with 29 million people and you haven’t thought to get translators on board? The U.S. Army was rounding up entire villages; rounding up old men and dragging them off, sending in units without a translator — company-sized units with 150 guys and no one speaks the language and they don’t have a translator with them.

AC: Is this a deeper problem in American culture or is it specific to the government, specific to the military? What do you think happened here?

MK: I think Americans don’t travel enough.

AC: But we never did.

MK: I think there was an incredible, almost breathtaking, degree of arrogance on the part of Washington and the politicians, who were very clear. They were like: “Who’s not going to want apple pie, democracy, Chevrolet, and everything we have?" And that’s so incredibly arrogant, and such a fundamental misunderstanding of what’s going on. It’s way more complicated than that.

WNYC's Leondard Lopate also spoke with Alan Chin, Michael Kamber and Ashley Gilbertson, who discussed trying to cover the war in Iraq and examine the role of the media and issues of censorship. Listen below:

AC: I realize the book is in English, not Arabic, but have you heard from Iraqis and other people in the Middle East who have seen the book?

MK: Yes, there’s an Iraqi journalists association that got in touch with me. They’re interested in possibly doing a piece about the book. I’d love to have it published in Arabic, that’s one of my dreams. I’d love to have it go around Iraq.

AC: How did you get the Iraqi photographers to participate?

MK: I had to get them in there. I interviewed seven or eight. It’s one of my regrets that only three are featured in the book. There are a couple other Arab photographers, but there are only three Iraqis in the book and I feel there should have been more. I ran out of time, we ran out of time and space. It’s my fault. I knew them from hanging out at the car bomb scenes, so they are all friends of mine.

AC: Do you think there was a difference between the way American and other foreign photographers approached the war and the way the Iraqis did themselves?

MK: I was pleasantly surprised and astonished at the degree of sacrifice these guys made, to really uphold the journalistic standards they’d been taught by the Western press when they came in. A lot of these guys had done their work under Saddam or they had no experience and were trained by people like Chris Hondros. They really took their work to heart and believed in it. They would sleep in the bureaus for months at a time because it was too dangerous to go home. Those guys were blown up, wounded, beaten, arrested. They were killed in huge numbers. They were at far, far, far greater danger than the Americans. They kept going back out. It was extraordinary.

AC: The book is dedicated to the 150 journalists who died. I would say, at least 140 were Iraqi.

MK: If you go to the Iraqi Journalists’ Union, they actually have a precise count that’s over 200. I went with the CPJ [Committee to Protect Journalists] number, which is lower. They have pictures of all of them. They have an entire wall that is pictures of dead Iraqi journalists.

THE LEGACY

AC: You talk a little bit about history, and a lot of the photographers have as well in their interviews. What do you want a future reader 20 years from now to think, looking at this book?

MK: You have to be careful about what you want people to think. You just have to show them and let them go with it. That’s why I wanted the book to be an oral history as opposed to me writing about the war and only telling my opinions. I wanted these people to tell their stories and let the reader decide once they see them.

AC: Dexter Filkins wrote about this in his introduction, photographers by and large -- traditionally, though I think it’s changing a lot -- are not known for what they have to say or write. “Pictures say a thousand words,“ or “I speak best through my pictures.” Do you think that’s changed? In this book and in the process you undertook to speak to everyone?

MK: A lot of photographers are not great writers. And that comes from people thinking, “Oh, they can’t communicate.” But they communicate beautifully. They have an oral tradition. Photographers tell stories all day long. Constantly telling stories. They might not all have gone through a Yale MFA writing program, but they are beautiful speakers, with a beautiful touch. They are observers.

AC: I don’t think anyone’s ever done this. I don’t think there is an oral history of photographers that covered the Vietnam War, or WWII.

MK: There should have been.

AC: There should have been. But there wasn’t.

MK: It has to be done by a photographer. It has to be somebody who was there.. If you didn’t go, then you’re going to get a different story. It’s got to be somebody familiar with the war, who was there, that other photographers trust to some degree. Most of them – they’re not all my friends, but a lot of them are my friends.. I wish somebody had done so, it would have been incredible to have an oral history of the Vietnam War; Larry Burroughs, Henri Huet, etc.

AC: And then years later they do this beautiful book, Requiem, which I’m sure you looked at. But that was published thirty years after it happened, and in that case, specifically addressing those who were killed. No one did it while they were alive.

MK: That’s an amazing book. But we need to have the conversation now. Afghanistan is winding down. Iraq, there’re car bombs going off every day in Iraq. I think there were 40 killed yesterday.

AC: But now that there are not Americans directly involved…

MK: …it’s a footnote.

AC: It’s an even smaller footnote.

THE AMERICAN PULLOUT

AC: Have you been back to Iraq?

MK: I left in January 2012. I haven’t been back.

AC: That’s fairly recent…that was the pullout?

MK: Yes. And I stayed another month.

AC: What was your sense of it? Was the pullout more PR than reality?

MK: It was a real pullout, as evidenced by the fact that the Iraqis said, “Don’t let the door hit you in the ass on your way out.” And basically opened up a police state the very next day. Actually, that very day. We crossed the border in the morning and in the afternoon they ordered the arrest of opposition leaders. It was a real pullout. They essentially said, “This is our country now. We’re going to do whatever we want.” Including sending arms to our enemies – in Syria – colluding very closely with our archenemy Iran, etc. They are their own country, very much so.

AC: On the street, was there a sense that it was safer or more normal?

MK: There is definitely a return to life. That’s been happening for a few years. The Americans have been largely off the streets for the last couple of years anyway.

AC: It wasn’t like when they were going toe-to-toe in neighborhoods anymore. What was your sense of the last American soldiers to leave?

MK: The military is so vast and diverse, so many different points of view. The higher up you go, the more obviously people are thinking about their careers and staying on message, but when you are out with the troops in the field, people speak whatever is on their minds and it’s a pretty interesting and diverse bunch.

I will say that, by 2010, 2011, that they were not going over there to avenge 9/11. And kill Osama bin Laden, which was what I used to hear in 2003.

AC: It’s a funny, funny thing, isn’t it?

MK: Quite a world out there.

AC: You have a daughter, and this is a bigger question, not just about your Iraq book, but what has she thought about “Michael Kamber, Photojournalist”?

MK: The whole experience was very terrifying for her. She was very close with Tim Hetherington. [Killed in Libya in 2011] She knows Joao Silva. [Lost both legs in Afghanistan in 2010] It’s always been terrifying.

AC: We've talked about the deaths of so many journalists — many of them friends — and the frustration about the seeming futility of war. Is the emotional impact on you something that you can describe? What keeps you going?

MK: The emotional impact is not something I can really describe except to say that I feel that prolonged proximity to violence makes one emotionally distant and somewhat cynical. Relationships and close friendships become almost impossible. One's threshold for what is important — what matters in day-to-day existence — becomes warped in a strange way. Only extremes register after a while and this makes it hard to relate to people doing "normal" things back home.

Nothing keeps me going. I've quit [covering war and conflict]. But I still feel that front line coverage of historical events — especially those where there are few witnesses — is one of the most important callings there is.

---

[The above is a lightly edited transcript of the conversation.]