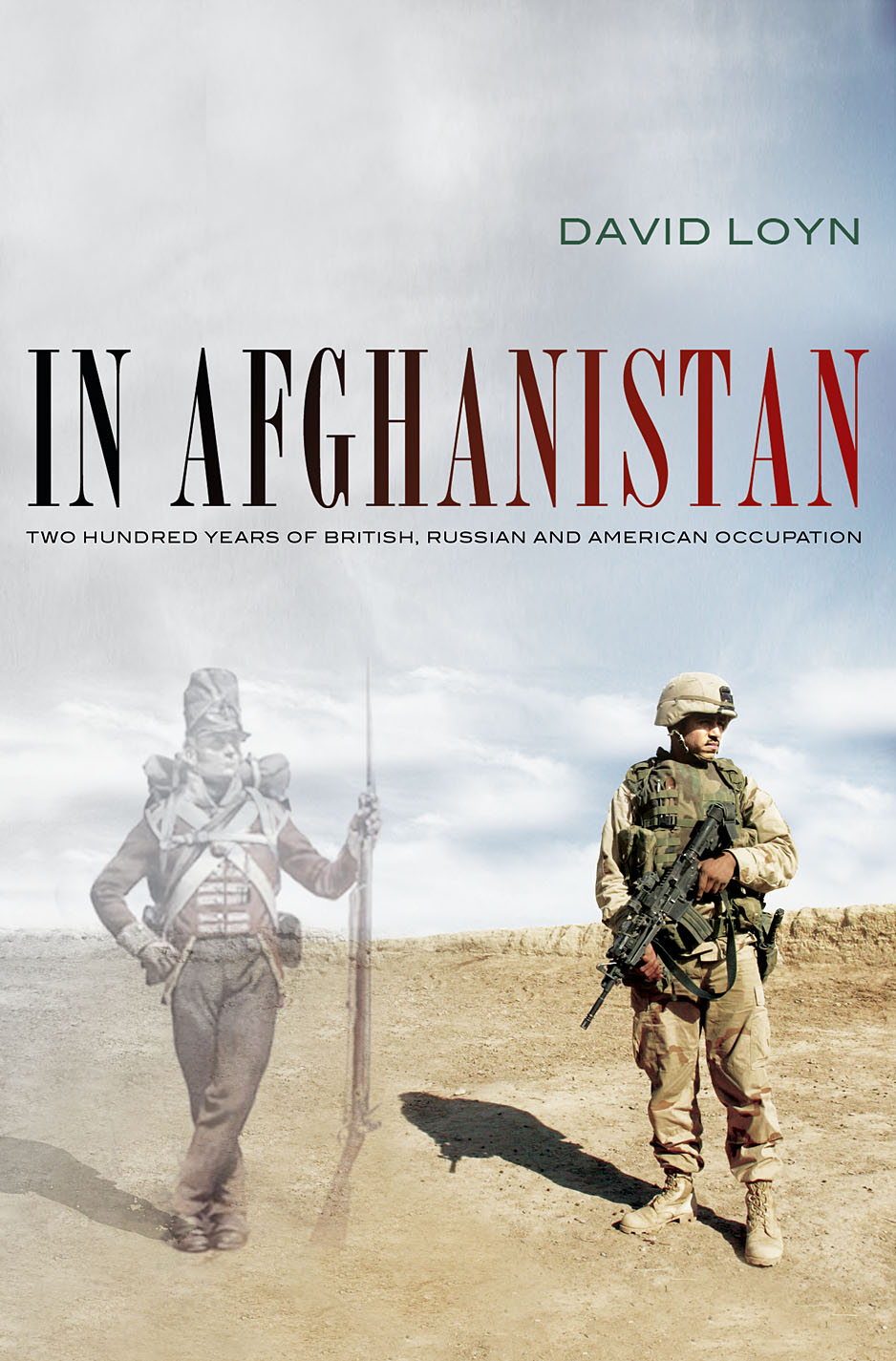

In Afghanistan

The BBC correspondent who witnessed the taking of Kabul in 1996 searches for an explanation of the Taliban in the history of a nation ruthless to its enemies but generous to its guests.

This article is an excerpt from David Loyn's new book "In Afghanistan: Two Hundred Years of British, Russian and American Occupation." Loyn will be talking about his reporting in Afghanistan as part of a Dart Center panel discussion with Sunday Times foreign affairs correspondent Christina Lamb on Wednesday, Oct. 6 at Columbia University in New York City.

I first heard the word Taliban on a Friday night in September 1994 over a beer in the colonial bungalow that served as the Foreign Correspondents’ Club in Delhi. A freelancer had just returned from the south of Afghanistan, where he had come across a new group of fighters using the name. “It might be worth checking them out,” he said. “The Taliban seem different to other mujahideen, they are some kind of student militia.” The Afghan conflict was then mired in a bloody stalemate 15 years after the Soviet invasion. We did not know that what he had witnessed was the beginning of something that would have implications far beyond Afghanistan.

Two years later, in September 1996, mine was the only TV crew to witness the Taliban takeover of Kabul, driving through the night toward the city past the wreckage of a defeated army. The pace and ruthlessness of the Taliban assault shook Afghanistan, putting more of the country under one administration than at any time since the Soviet invasion. Five years later, in 2001, the Taliban were targeted as the hosts of the 9/11 attackers and forced out after a war that was a technical triumph, victory without tears, at least for the United States, which suffered no combat fatalities. But by 2008 the number of foreign forces in the country rose to 50,000 for the first time, and a call went out for more, to tackle a worsening insurgency.

What had gone wrong? When the Taliban were ousted, few in Afghanistan appeared to lament the fall of these fundamentalist zealots. But that did not take long to change. The Taliban never went away and emerged from underground to win new supporters. The international community had made some fundamental mistakes after 2001, as what the World Bank would call an “aid juggernaut” drove into town, providing funds for itself and living in a parallel world rather than building a new Afghan state. Corruption was allowed to flourish, driven by huge profits from illegal drugs. And a military campaign had focused on arresting terrorists rather than restoring order. But were those failures enough to explain the resurgent Taliban?

Afghanistan had long ago built a reputation of resistance to foreign invaders. In 2009, it is exactly 200 years since Mounstuart Elphinstone, a Scottish political officer working for the Raj, Britain’s administration in India, was the first formal envoy sent by any European power to discover who ruled the “Kingdom of Caubul.” Another 30 years passed before Britain would attempt its first military expedition. That first war ended in catastrophe, and in the years that followed Afghanistan would inflict other defeats on British forces; Persia and Russia made even less headway. None seemed to learn any lessons from history. As a reporter traveling in Afghanistan, I wondered if there really was something in the nature of the people and the country itself that made it so hard to conquer.

Afghanistan was the farthest outpost of the region I covered as the BBC’s South Asia correspondent in the mid-1990s, and the common complaint at the club bar was that it was then a forgotten war. Editors were not easily persuaded to invest in travel to a country locked in the confusing and bitter conflict that followed the pullout of Soviet troops in 1989. Besides, it was very dangerous, as I was reminded when a local journalist working for the BBC, Mirwais Jalil, was targeted and killed in cold blood in July 1994. Fighting in those years between rival mujahideen did far more damage to Kabul than the preceding decade of guerrilla warfare against the Soviet invasion, but received hardly any coverage worldwide.

Journalists who ventured there told of narrow escapes in a city that crackled with the constant sound of gunfire, their days spent risking movement through hostile checkpoints and their nights sleeping in basements with a shovel nearby to dig themselves out if the house above was struck by a rocket. They told tales too of the resilience and hospitality of Afghans despite everything, with an honor code — the pashtunwali — that meant that although Afghans were ruthless to their enemies, they would risk their own lives to guarantee the safety of their guests.

Journalists who ventured there told of narrow escapes in a city that crackled with the constant sound of gunfire, their days spent risking movement through hostile checkpoints and their nights sleeping in basements with a shovel nearby to dig themselves out if the house above was struck by a rocket. They told tales too of the resilience and hospitality of Afghans despite everything, with an honor code — the pashtunwali — that meant that although Afghans were ruthless to their enemies, they would risk their own lives to guarantee the safety of their guests.

I saw this in action 20 years later in October 2006 when I interviewed a senior Taliban commander in Helmand Province, who was leading the renewed campaign against British troops. The invitation came from the Taliban, and my safety depended on his word, a system tested when a group of battle-weary fighters arrived after a gun battle with British soldiers and said they wanted to shoot me. In the subsequent argument for my life, he resisted their demands to hand me over, saying they would have to kill him first.