Lasting Scars

This three-part series exposes the hidden legacy of torture perpetrated by the United States at C.I.A. prisons and Guantanamo, and examines the long-term consequences on prisoners. Judges called it “incredibly important journalism,” and commended it for providing “a new angle on the urgent topic of torture.” Originally published by The New York Times in October and November, 2016.

SERIES ELEMENTS:

How U.S. Torture Left a Legacy of Damaged Minds

Memories of a Secret C.I.A. Prison

After Torture, Ex-Detainee Is Still Captive of ‘The Darkness’

Where Even Nightmares Are Classified: Psychiatric Care at Guantánamo

Secret Documents Show a Tortured Prisoner's Descent

How U.S. Torture Left a Legacy of Damaged Minds

How U.S. Torture Left a Legacy of Damaged Minds

Beatings, sleep deprivation, menacing and other brutal tactics have led to persistent mental health problems among detainees held in secret C.I.A. prisons and at Guantánamo.

By Matt Apuzzo, Sheri Fink and James Risen, Originally published by The New York Times on October 8, 2016

Before the United States permitted a terrifying way of interrogating prisoners, government lawyers and intelligence officials assured themselves of one crucial outcome. They knew that the methods inflicted on terrorism suspects would be painful, shocking and far beyond what the country had ever accepted. But none of it, they concluded, would cause long lasting psychological harm.

Fifteen years later, it is clear they were wrong.

Today in Slovakia, Hussein al-Marfadi describes permanent headaches and disturbed sleep, plagued by memories of dogs inside a blackened jail. In Kazakhstan, Lutfi bin Ali is haunted by nightmares of suffocating at the bottom of a well. In Libya, the radio from a passing car spurs rage in Majid Mokhtar Sasy al-Maghrebi, reminding him of the C.I.A. prison where earsplitting music was just one assault to his senses.

And then there is the despair of men who say they are no longer themselves. “I am living this kind of depression,” said Younous Chekkouri, a Moroccan, who fears going outside because he sees faces in crowds as Guantánamo Bay guards. “I’m not normal anymore.”

After enduring agonizing treatment in secret C.I.A. prisons around the world or coercive practices at the military detention camp at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, dozens of detainees developed persistent mental health problems, according to previously undisclosed medical records, government documents and interviews with former prisoners and military and civilian doctors. Some emerged with the same symptoms as American prisoners of war who were brutalized decades earlier by some of the world’s cruelest regimes.

Those subjected to the tactics included victims of mistaken identity or flimsy evidence that the United States later disavowed. Others were foot soldiers for the Taliban or Al Qaeda who were later deemed to pose little threat. Some were hardened terrorists, including those accused of plotting the Sept. 11 attacks or the 2000 bombing of the American destroyer Cole. In several cases, their mental status has complicated the nation’s long effort to bring them to justice.

Americans have long debated the legacy of post-Sept. 11 interrogation methods, asking whether they amounted to torture or succeeded in extracting intelligence. But even as President Obama continues transferring people from Guantánamo and Donald J. Trump, the Republican presidential nominee, promises to bring back techniques, now banned, such as waterboarding, the human toll has gone largely uncalculated.

At least half of the 39 people who went through the C.I.A.’s “enhanced interrogation” program, which included depriving them of sleep, dousing them with ice water, slamming them into walls and locking them in coffin-like boxes, have since shown psychiatric problems, The New York Times found. Some have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, paranoia, depression or psychosis.

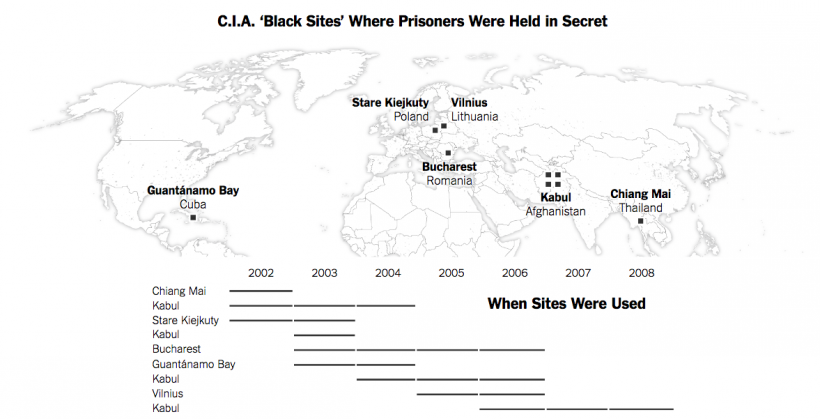

Hundreds more detainees moved through C.I.A. “black sites” or Guantánamo, where the military inflicted sensory deprivation, isolation, menacing with dogs and other tactics on men who now show serious damage. Nearly all have been released.

“There is no question that these tactics were entirely inconsistent with our values as Americans, and their consequences present lasting challenges for us as a country and for the individuals involved,” said Ben Rhodes, the deputy national security adviser.

The United States government has never studied the long-term psychological effects of the extraordinary interrogation practices it embraced. A Defense Department spokeswoman, asked about long-term mental harm, responded that prisoners were treated humanely and had access to excellent care. A C.I.A. spokesman declined to comment.

This article is based on a broad sampling of cases and an examination of hundreds of documents, including court records, military commission transcripts and medical assessments. The Times interviewed more than 100 people, including former detainees in a dozen countries. A full accounting is all but impossible because many former prisoners never had access to outside doctors or lawyers, and any records about their interrogation treatment and health status remain classified.

Researchers caution that it can be difficult to determine cause and effect with mental illness. Some prisoners of the C.I.A. and the military had underlying psychological problems that may have made them more susceptible to long-term difficulties; others appeared to have been remarkably resilient. Incarceration, particularly the indefinite detention without charges that the United States devised, is inherently stressful. Still, outside medical consultants and former government officials said they saw a pattern connecting the harsh practices to psychiatric issues.

Those treating prisoners at Guantánamo for mental health issues typically did not ask their patients what had happened during their questioning. Some physicians, though, saw evidence of mental harm almost immediately.

“My staff was dealing with the consequences of the interrogations without knowing what was going on,” said Albert J. Shimkus, a retired Navy captain who served as the commanding officer of the Guantánamo hospital in the prison’s early years. Back then, still reeling from the Sept. 11 attacks, the government was desperate to stave off more.

But Captain Shimkus now regrets not making more inquiries. “There was a conflict,” he said, “between our medical duty to our patients and our duty to the mission, as soldiers.”

After prisoners were released from American custody, some found neither help nor relief. Mohammed Abdullah Saleh al-Asad, a businessman in Tanzania, and others were snatched, interrogated and imprisoned, then sent home without explanation. They returned to their families deeply scarred from interrogations, isolation and the shame of sexual taunts, forced nudity, aggressive body cavity searches and being kept in diapers.

Mr. Asad, who died in May, was held for more than a year in several secret C.I.A. prisons. “Sometimes, between husband and wife, he would admit to how awful he felt,” his widow, Zahra Mohamed, wrote in a statement prepared for the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. “He was humiliated, and that feeling never went away.”

Bryan Denton for The New York Times: Lutfi bin Ali, a former detainee now living in Kazakhstan, has chronic health problems and undergoes physical therapy for injuries he sustained in custody.

‘A Human Mop’

In a cold room once used for interrogations at Guantánamo, Stephen N. Xenakis, a former military psychiatrist, faced a onetime Qaeda child soldier, Omar Khadr. It was December 2008, and this evaluation had been two years in the making.

The doctor, a retired brigadier general who had overseen several military hospitals, had not sought the assignment. The son of an Air Force combat veteran, he debated even accepting it. “I’m still a soldier,” General Xenakis recalls thinking. Was this good for the country? When he finally agreed, he told Mr. Khadr’s lawyers that they were paying for an independent medical opinion, not a hired gun.

Mr. Khadr, a Canadian citizen, had been wounded and captured in a firefight at age 15 at a suspected terrorist compound in Afghanistan, where he said he had been sent to translate for foreign fighters by his father, a Qaeda member. Years later, he would plead guilty to war crimes, including throwing a grenade that killed an Army medic. At the time, though, he was the youngest prisoner at Guantánamo.

He told his lawyers that the American soldiers had kept him from sleeping, spit in his face and threatened him with rape. In one meeting with the psychiatrist, Mr. Khadr, then 22, began to sweat and fan himself, despite the air-conditioned chill. He tugged his shirt off, and General Xenakis realized that he was witnessing an anxiety attack.

When it happened again, Mr. Khadr explained that he had once urinated during an interrogation and soldiers had dragged him through the mess. “This is the room where they used me as a human mop,” he said.

“I have dreams of being at the bottom of a well and being suffocated.”

LUTFI BIN ALI, released without charge after 12 years. Semey, Kazakhstan

General Xenakis had seen such anxiety before, decades earlier, as a young psychiatrist at Letterman Army Medical Center in California. It was often the first stop for American prisoners of war after they left Vietnam. The doctor recalled the men, who had endured horrific abuses, suffering panic attacks, headaches and psychotic episodes.

That session with Mr. Khadr was the beginning of General Xenakis’s immersion into the treatment of detainees. He has reviewed medical and interrogation records of about 50 current and former prisoners and examined about 15 of the detainees, more than any other outside psychiatrist, colleagues say.

General Xenakis found that Mr. Khadr had post-traumatic stress disorder, a conclusion the military contested. Many of General Xenakis’s diagnoses in other cases remain classified or sealed by court order, but he said he consistently found links between harsh American interrogation methods and psychiatric disorders.

Back home in Virginia, General Xenakis delved into research on the effects of abusive practices. He found decades of papers on the issue — science that had not been considered when the government began crafting new interrogation policies after Sept. 11.

At the end of the Vietnam War, military doctors noticed that former prisoners of war developed psychiatric disorders far more often than other soldiers, an observation also made of former P.O.W.s from World War II and the Korean War. The data could not be explained by imprisonment alone, researchers found. Former soldiers who suffered torture or mistreatment were more likely than others to develop long-term problems.

By the mid-1980s, the Veterans Administration had linked such treatment to memory loss, an exaggerated startle reflex, horrific nightmares, headaches and an inability to concentrate. Studies noted similar symptoms among torture survivors in South Africa, Turkey and Chile. Such research helped lay the groundwork for how American doctors now treat combat veterans.

“In hindsight, that should have come to the fore” in the post-Sept. 11 interrogation debate, said John Rizzo, the C.I.A.’s top lawyer at the time. “I don’t think the long-term effects were ever explored in any real depth.”

Instead, the government relied on data from a training program to resist enemy interrogators, called SERE, for Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape. The military concluded there was little evidence that disrupted sleep, near-starvation, nudity and extreme temperatures harmed military trainees in controlled scenarios.

Two veteran SERE psychologists, James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen, worked with the C.I.A. and the Pentagon to help develop interrogation tactics. They based their strategies in part on the theory of “learned helplessness,” a phrase coined by the American psychologist Martin E. P. Seligman in the late 1960s. He gave electric shocks to dogs and discovered that they stopped resisting once they learned they could not stop the shocks. If the United States could make men helpless, the thinking went, they would give up their secrets.

In the end, Justice Department lawyers concluded that the methods did not constitute torture, which is illegal under American and international law. In a series of memos, they wrote that no evidence existed that “significant psychological harm of significant duration, e.g., lasting for months or even years” would result.

With fear of another terrorist attack, there was little incentive or time to find contrary evidence, Mr. Rizzo said. “The government wanted a solution,” he recalled. “It wanted a path to get these guys to talk.”

The question of what ultimately happened to Dr. Seligman’s dogs never arose in the legal debate. They were strays, and once the studies were over, they were euthanized.

A Sense of Drowning

Mohamed Ben Soud cannot say for certain when the Americans began using ice water to torment him. The C.I.A. prison in Afghanistan, known as the Salt Pit, was perpetually dark, so the days passed imperceptibly.

The United States called the treatment “water dousing,” but the term belies the grisly details. Mr. Ben Soud, in court documents and interviews, described being forced onto a plastic tarp while naked, his hands shackled above his head. Sometimes he was hooded. One C.I.A. official poured buckets of ice water on him as others lifted the tarp’s corners, sending water splashing over him and causing a choking or drowning sensation. He said he endured the treatment multiple times.

Mr. Ben Soud was among the early captives in the C.I.A.’s network of prisons in Afghanistan, Thailand, Poland, Romania and Lithuania. Again and again, he said, he told the American interrogators that he was not their enemy. A Libyan, he said he had fled to Pakistan in 1991 and joined an armed Islamist movement aimed at toppling Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi’s dictatorship. Pakistani and United States officials stormed his home and arrested him in 2003. Under interrogation, he said, he denied knowing or fighting with Osama bin Laden or two senior Qaeda operatives.

In 2004, the C.I.A. turned Mr. Ben Soud over to Libya, which imprisoned him until the United States helped topple the Qaddafi government seven years later. In interviews, he and other Libyans said they were treated better by Colonel Qaddafi’s jailers than by the C.I.A.

Today, Mr. Ben Soud, 47, is a free man, but said he is in constant fear of tomorrow. He is racked with self-doubt and struggles to make simple decisions. His moods swing dramatically.

“‘Dad, why did you suddenly get angry?’ ‘Why did you suddenly snap?’” Mr. Ben Soud said his children ask. “‘Did we do anything that made you angry?’”

Explaining would mean saying that the Americans kept him shackled in painful contortions, or that they locked him in boxes — one the size of a coffin, the other even smaller, he said in a phone interview from his home in Misurata, Libya. They slammed him against the wall and chained him from the ceiling as the prison echoed with the sounds of rock music.

“How can you explain such things to children?” he asked.

Mr. Ben Soud, along with a second former C.I.A. prisoner and the estate of a third, is suing Dr. Mitchell and Dr. Jessen in federal court, accusing them of violating his rights by torturing him. In court documents, Dr. Mitchell and Dr. Jessen argue, among other things, that they played no role in the interrogations.

Mr. Ben Soud was one of the men identified in a 2014 Senate Intelligence Committee report as having been subjected to the C.I.A.’s “enhanced interrogation techniques.” Condemning the methods as brutal and ineffective in extracting intelligence, the report noted that interrogators also used unapproved tactics such as mock executions, threats to harm prisoners’ children or rape their family members, and “rectal feeding,” which involved inserting liquid food supplements or purées into the rectum.

Senate investigators did not set out to study the psychological consequences of the harsh treatment, but their unclassified summary revealed several cases of men suffering hallucinations, depression, paranoia and other symptoms. The full 6,000-page classified report offers many more examples, said Daniel Jones, a former F.B.I. analyst who led the Senate investigation.

“The records we reviewed clearly indicate a connection between their treatment in C.I.A. custody and their mental state,” Mr. Jones said in an interview.

“You realize it was a nightmare, but still you feel afraid and shaking with fear.”

KHALED AL-SHARIF, rendered to Libya in 2004 after two years in C.I.A. secret prisons. Tripoli, Libya

At least 119 men moved through the C.I.A. jails, where the interrogations were designed to disrupt the senses and increase helplessness — factors that researchers decades earlier had said could make people more susceptible to psychological harm. Forced nudity, sensory deprivation and endless light or dark were considered routine.

Many of those men were later released without charges, unsure of why they were held. About one in four prisoners should never have been captured, or turned out to have been misidentified by the C.I.A., Senate investigators concluded. Khaled el-Masri, a German citizen, is the best known case.

Macedonian authorities arrested him while he was on vacation in December 2003 and turned him over to the C.I.A. Mr. Masri said officials beat him, stripped him, forced a suppository into him and flew him to a black site in Afghanistan. He was held for months, he said, in a concrete cell with no bed, and endured more beatings and interrogations.

Years later, Mr. Masri’s nightmares are accompanied by a paralyzing tightness in his chest, he said. “I have been suffering from absent-mindedness, amnesia, inability to memorize, depression, helplessness, apathy, loss of interest in the future, slow thinking, and anxiety,” Mr. Masri wrote in an email.

Ms. Mohamed, the widow of Mr. Asad, the Tanzanian businessman, said he returned home paranoid and anxious.

“He used to forget things that he never would have forgotten before,” she wrote recently. “For example, he would talk with someone on the phone and later forget to whom he had been talking.”

Mr. Asad believed the C.I.A. seized him because he once rented space in a building he owned to Al Haramain Foundation, a Saudi charity later linked to financing terrorism. Interrogators questioned him repeatedly about the charity, he said in legal papers, then released him with no explanation.

“Mohammed’s personality changed after his detention,” his wife wrote. “Something tiny would happen and he would blow up — he would be so angry — I had never ever seen him like this before. At these times, he would come close to crying, and he would withdraw to be alone.”

‘Still Living in Gitmo’

Today at Guantánamo Bay, the Caribbean landscape is reclaiming the relics of the American detention system. Weeds overtake fences in abandoned areas of the prison complex. Guard towers sit empty. It is eerily quiet.

President Obama banned coercive questioning on his second day in office and his administration has whittled the prison population to 61, down from nearly 700 at its peak. Interrogations ended long ago. Except for the so-called high-value detainees, kept in a building hidden in the hills, most of the remaining prisoners share a concrete jail called Camp 6.

Asked about their psychological well-being, Rear Adm. Peter J. Clarke, the commander at Guantánamo, said in an interview: “What I observe are detainees who are well adjusted, and I see no indications of ill effects of anything that may have happened in the past.”

In the early years of Guantánamo, interrogators used variations on some of the C.I.A.’s tactics. The result was a combination of psychological and physical pressure that the International Committee of the Red Cross found was “tantamount to torture.”

Capt. Richard Quattrone of the Navy, who left his post as the prison’s chief medical officer in September, said his staff mostly dealt with detainees’ anxiety over whether they would be released. “I’ve talked to some of my predecessors,” he said in an interview, “and from what they say, it’s vastly different today.”

About 20 detainees are cleared for release. Another 10 are being prosecuted or have already been convicted in military commissions. The fate of the remaining men, including some of the high-value prisoners, is unclear. For now they are considered too dangerous to release, but have not been charged.

For some men who have been released, Guantánamo is not easily left behind. Mr. Chekkouri, a Moroccan living in Afghanistan in 2001, was held for years as a suspected member of a group linked to Al Qaeda. He said he was beaten repeatedly at a United States military jail in Kandahar and forced to watch soldiers do the same to his younger brother.

Mr. Chekkouri is a Sufi, a member of a mystical Islamic sect that has been oppressed by Al Qaeda and others. At Guantánamo, he was kept in isolation.

When he asserted his innocence, he said, interrogators threatened to turn him over to the Moroccan authorities, who have a history of torture. The Americans warned that his family in Morocco could be jailed and abused, he said, and showed him execution photos. Interrogators repeatedly made him believe his transfer was imminent, he said. “It’s time to say goodbye,” interrogation files cited in court documents say. “Morocco wants you back.”

After he was released last year, the United States gave him a letter saying it no longer stood by information that he was a member of a Qaeda-linked group in Morocco. Despite diplomatic assurances that he would face no charges, Morocco jailed him for several months late last year and he continues to fight allegations that he thought were behind him.

Now, he is under a psychiatrist’s care and takes antidepressants and anti-anxiety drugs. He complains of flashbacks, persistent nightmares and panic attacks. He also suffers an embarrassing inability to urinate until it becomes painful. It started, he said, when he was left chained for hours during interrogations and soiled himself. His doctors say there is nothing they can treat.

“They tell me everything is normal,” he said. “Your brain is playing games. It is something mental. You’re still living in Gitmo. It’s fear.”

“It’s like I’m trapped. I stay all day in my house alone.”

YOUNOUS CHEKKOURI, released without charge after more than 13 years. Safi, Morocco

Mr. Chekkouri saw psychiatrists at Guantánamo, but he said he did not trust them. He and others believed the doctors shared information about medical problems with interrogators. In one case, a psychiatrist prescribed the antipsychotic medication olanzapine to a prisoner. He then suggested that interrogators exploit a side effect, food cravings, according to another military doctor who later reviewed the records.

Normally, such information would be confidential, but Guantánamo’s dual missions of caring for prisoners and extracting information created conflicts. Over time, the military created two mental health teams. One, led by psychiatrists, was there to heal. The other, called the Behavioral Science Consultation Team, was led by psychologists with a very different mission.

On Sept. 3, 2003, after a teenager named Mohammed Jawad was seen talking to a poster on the wall, an interrogator called for a consultation with a BSCT (pronounced “Biscuit”) psychologist. Mohammed’s age at the time is in dispute. The military says it captured him at 17; his lawyer says he was more likely 14 or younger. However old, he was pleading for his mother.

When the psychologist arrived, the goal was not to ease the young man’s distress, but to exploit it.

“The detainee comes across as a very immature, dependent individual, claiming to miss his mother and his young siblings, but his demeanor looks like it is a resistance technique,” the psychologist wrote, according to notes seen by The Times. “He tries to look as if he is so sad that he is depressed. During today’s interrogation, he appeared to be rather frightened, and it looks as if he could easily break.”

The psychologist, who was not identified in the notes, recommended that Mr. Jawad be kept away from anyone who spoke his language. “Make him as uncomfortable as possible,” the psychologist advised. “Work him as hard as possible.”

The guards placed him in isolation for 30 days. They then subjected him to the “frequent flier program,” a method of sleep deprivation. Guards yanked Mr. Jawad from cell to cell 112 times, waking him an average of every three hours, day and night, for two weeks straight, according to court records.

After being held for years, Mr. Jawad was charged in 2007 with throwing a grenade that wounded American soldiers. But the evidence collapsed. The military prosecutor, Lt. Col. Darrel Vandeveld, withdrew from the case and declared that there was no evidence to justify charges. “There is, however, reliable evidence that he was badly mistreated by U.S. authorities, both in Afghanistan and at Guantánamo, and he has suffered, and continues to suffer, great psychological harm,” he wrote in a letter to the court.

Katherine Porterfield, a New York University psychologist, found Mr. Jawad to have PTSD after examining him in 2009. Seven years after his capture, she said, he suffered from flashbacks and anxiety attacks. A panel of military doctors disagreed. Medical records from Guantánamo include repeated notes such as “no psych issues at this time,” or the prisoner “denied any psych problem.”

The military dropped all charges against Mr. Jawad, who is now living in Pakistan. He declined to discuss his mental health. But in a series of text messages, he wrote: “They tortured us in jails, gave us severe physical and mental pain, bombarded our villages, cities, mosques, schools.” He added, “Of course we have” flashbacks, panic attacks and nightmares.

Ignoring a Link

It has been difficult to determine the scale of mental health problems at Guantánamo, much less how many cases are linked to the treatment the prisoners endured. Most medical records remain classified. Anecdotal accounts, though, have emerged over the years.

Andy Davidson, a retired Navy captain who served as the chief psychologist treating prisoners at Guantánamo from July to October 2003, said most appeared to be in good health, but he still saw “an awful lot” of mental health issues there.

“There were definitely guys who had PTSD symptoms,” he said in an interview. “There were definitely guys who had poor sleeping, nightmares. There were guys who were definitely shell shocked with a thousand-mile stare. There were guys who were depressed, avoidant.”

One of the few official glimpses into the population came in a 2006 medical journal article. Two military psychologists and a psychiatrist at Guantánamo wrote that about 11 percent of detainees were then receiving mental health services, a rate lower than that in civilian jails or among former American prisoners of war. The authors acknowledged, however, that Guantánamo doctors faced significant challenges in diagnosing mental illness, most notably the difficulty in building trust. Many prisoners, including some with serious mental health conditions, refused evaluation and treatment, the study noted, which would have lowered the count.

Five years later, General Xenakis and Vincent Iacopino, the medical director for Physicians for Human Rights, published research about nine prisoners who exhibited psychological symptoms after undergoing interrogation tactics — a hose forced into a mouth, a head held in a toilet, death threats — by American jailers.

The two based their study on the medical records and interrogation files of the prisoners, all of whom had arrived at Guantánamo in its first year, had never been in C.I.A. custody, and were never charged with any crimes. In none of those cases, the study said, did Guantánamo doctors document any inquiries into whether the symptoms were tied to interrogation tactics.

“It is very, very scary when you are tortured by someone who doesn’t believe in torture. You lose faith in everything.”

AHMED ERRACHIDI, released without charge after five years. Tangier, Morocco

Today in Tangier, Morocco, Ahmed Errachidi runs two restaurants, has a wife and five children and has been free for nearly a decade. The United States military once asserted that he trained at a Qaeda camp in early 2001, but the human rights group Reprieve later produced pay stubs showing that he had been working at the time as a cook in London.

Mr. Errachidi had a history of bipolar disorder before arriving at Guantánamo, and after being held in isolation there, he said, he suffered a psychotic breakdown. He told interrogators that he had been Bin Laden’s superior officer and warned that a giant snowball would overtake the world.

Guantánamo still lurks around corners. Recently, at a market in Tangier, the clink of a chain caused a paralyzing flashback to the prison, where Mr. Errachidi was forced into painful stress positions, deprived of sleep and isolated. On chilly nights, when the blanket slips off, he is once again lying naked in a frigid cell, waiting for his next interrogation.

“All I can think of is when are they going to take me back,” Mr. Errachidi said in an interview. He compared his treatment by the Americans to being mugged by a trusted friend. “It is very, very scary when you are tortured by someone who doesn’t believe in torture,” he said. “You lose faith in everything.”

Guantánamo, particularly during its early years, operated on a system of rewards and punishments to exploit prisoners’ vulnerabilities. That manipulation, taken to extremes, could have dangerous effects, as in the peculiar case of Tarek El Sawah.

An Egyptian who said he was a Taliban soldier, Mr. Sawah was captured while fleeing bombing in Afghanistan in 2001 and turned over to the United States. He arrived at Guantánamo in May 2002. Though his brother, Jamal, said he had no history of mental problems, Mr. Sawah began shrieking at night, terrified by hallucinations.

When he began defecating and urinating on himself, soldiers would hose him down in front of other detainees, a nearby prisoner stated in court documents. Mr. Sawah said he was given antipsychotic drugs, sometimes forcibly.

After his breakdown, interrogators found Mr. Sawah eager to talk. “‘Bring me good things to eat,’” he told them. They delivered McDonald’s hamburgers or Subway sandwiches, multiple servings at a time.

Mr. Sawah became a prized informant, though the value of what he offered is disputed, and he says he fabricated stories, including that he was a Qaeda member. He ballooned from about 215 pounds to well over 400 pounds, records show. When the interrogations ended and he was placed in a special hut for cooperators, the food kept coming. His jailers had to install a double-wide door for him.

“They were afraid of me, afraid for their life. Guantánamo on both sides was just very scared people who want to live.”

TAREK EL SAWAH, released without charge after 14 years. Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Mr. Sawah called it a competition between the interrogators, who used food as an incentive, and the doctors, who told him to lose weight. He developed coronary artery disease, diabetes, breathing disorders and other health problems, court records show.

In 2013, General Xenakis examined him and, in a plea for better medical treatment, told a judge that “Mr. El Sawah’s mental state has worsened and he appears apathetic with diminished will to live.” The military responded that he was offered excellent medical care but refused it.

Today in Bosnia, Mr. Sawah, 58, complains of frequent headaches and begs a doctor for antidepressants. His mood fluctuates wildly. Though he has lost weight, his eating remains compulsive. Over dinner with a reporter after a daily Ramadan fast, he ate a steak, French fries, a plate of dates and figs, a bowl of chicken soup, spinach pie, slices of bread, the uneaten portion of another steak, another bowl of soup, two lemonades, a Coke and nearly an entire cheese plate, six or seven slices at a time.

“He’s unbalanced,” said his brother, who lives in New York. “He needs care. Mental care. Physical care.”

Mr. Sawah does not blame American soldiers for his treatment. “They were afraid of me, afraid for their life,” he said. “Guantánamo on both sides was just very scared people who want to live.”

Complicating Trials

In a war-crimes courtroom at Guantánamo Bay in January 2009, five men sat accused of plotting the Sept. 11 attacks. They were avowed enemies of the United States, who had admitted to grievous bloodshed. They had also been subjected to the most horrific of the government’s interrogation tactics.

During a courtroom break, one of the men, Ammar al-Baluchi, asked to speak with a doctor. Xavier Amador, a New York psychologist who was consulting for another defendant, met with him. As they talked, Mr. Baluchi’s eyes darted around the room, according to a summary of Dr. Amador’s notes obtained by The Times. Mr. Baluchi said he struggled to focus, described “terrifying anxiety” and reported difficulty sleeping.

Dr. Amador noted that Mr. Baluchi seemed to meet the criteria for PTSD, anxiety disorder and major depression. “No one can live like this,” Mr. Baluchi told him.

Mr. Baluchi, 39, was captured by Pakistani officers in April 2003. Though he was described as willing to talk, the C.I.A. moved him to a secret prison and immediately applied interrogation methods reserved for recalcitrant prisoners. In court documents and Mr. Baluchi’s handwritten letters, he described being naked and dehydrated, chained to the ceiling so only his toes touched the floor. He endured ice-water dousing and said he was beaten until he saw flashes of light and lost consciousness. He recalls punches from his guards whenever he drifted asleep.

Today, his lawyer said, Mr. Baluchi associates sleep with imminent pain. “Not only did they not let me sleep,” Mr. Baluchi wrote in a letter provided by the lawyer, “they trained me to keep myself awake.”

Guantánamo physicians have prescribed Mr. Baluchi antidepressants, anti-anxiety drugs and sleeping pills, according to his lawyer, James G. Connell III, who sends him deodorants and colognes to keep flashbacks at bay. “The whole time he was in C.I.A. custody, you’re sitting there, smelling your own stink,” Mr. Connell said. “Now, whenever he catches a whiff of his own body odor, it sets him off.”

General Xenakis, who is consulting on the case, found that Mr. Baluchi had PTSD and that he showed possible signs of a brain injury that may be linked to his beatings. He said Mr. Baluchi needed a brain scan, which the military opposes. The test would likely prompt more hearings, which could further complicate a trial.

“Having caused these problems in the first place, now the United States has to deal with them at the military commissions,” Mr. Connell said. “And that takes time.”

The compromised mental status of several other prisoners, like Mr. Baluchi, has affected the military proceedings against them.

Ramzi bin al-Shibh, who admits helping plan the Sept. 11 attacks, has said he believes the military is tormenting him with vibrations, smells and sounds at Guantánamo. Military doctors there have found him to be delusional, and records indicate that his symptoms began in C.I.A. custody, after brutal tactics and years of solitary confinement.

But Mr. bin al-Shibh refused to meet with doctors to assess his competency and insists he is sane, so the case continues.

Lawyers have similarly raised questions about Abd al-Nashiri’s psychological state. Accused in the U.S.S. Cole bombing, he was subjected to waterboarding, mock execution, rectal feeding and other techniques — some approved, some not — at C.I.A. sites. Even after internal warnings that Mr. Nashiri was about to go “over the edge psychologically,” the C.I.A. pressed forward.

Over the years, government doctors have diagnosed Mr. Nashiri with anxiety, major depression and PTSD. His lawyers do not dispute his competency to stand trial, though no such trial is imminent. His torture and mental decline, though, could make it harder for prosecutors to win a death sentence.

When the Walter Reed doctors evaluated Mr. Nashiri, “they concluded that he suffers from chronic, complex, untreated PTSD,” his lawyer told a military judge in 2014. “And they attributed it to his time in C.I.A. custody.”

“They killed our youth in Guantánamo and then they tossed us away like garbage.”

HUSSEIN AL-MARFADI, released without charge after 12 years. Zvolen, Slovakia

Interrogation’s Shadow

In Libya today, a former C.I.A. prisoner named Salih Hadeeyah al-Daeiki struggles to focus, and his memory fails him. He finds himself confusing the names of his children. Sometimes, he withdraws from his family to be alone.

A survivor of the C.I.A. interrogation in the Salt Pit, Mr. Daeiki says he was kept naked, humiliated and chained to the wall as loud music blared. Sleep is difficult now, but when it comes, his interrogators haunt him there.

“Something is strangling me or I’m falling from high,” he said in an interview. “Or sometimes I see ghosts following me, chasing me.”

Last year, a video surfaced showing Colonel Qaddafi’s son, Saadi, being blindfolded and forced to listen to what sounded like the screams of other prisoners inside Al Hadba, a prison holding members of the former regime — Libya’s own high-value detainees. Someone beat the soles of his feet with a stick.

As the scene unfolded, Mr. Daeiki appeared on the screen.

The beating was a mistake, he later acknowledged, but he did nothing to stop it. The goal was to collect intelligence to prevent bloodshed, he said.

He was an interrogator now.

Memories of a Secret C.I.A. Prison

Memories of a Secret C.I.A. Prison

By Neil Collier and Sheri Fink, Originally published by The New York Times on October 8, 2016

Khaled al-Sharif spent two years in a secret C.I.A. prison, accused of having ties to Al Qaeda. He tells New York Times correspondent Sheri Fink what happened there, and how the experience continues to affect him.

After Torture, Ex-Detainee Is Still Captive of ‘The Darkness’

After Torture, Ex-Detainee Is Still Captive of ‘The Darkness’

The United States subjected Suleiman Abdullah Salim to harsh tactics in a secret prison and held him without charge for years. He was found not to be a terrorist threat, but he pays a deep price to this day.

By James Risen, Originally published by The New York Times on October 12, 2016

Suleiman Abdullah Salim endured beatings, sleep deprivation, water dousing and other severe measures.

“They said, ‘You changed your face,’” Mr. Salim, a Tanzanian, recalled the American men telling him when he arrived. “They said: ‘You are Yemeni. You changed your face.’”

That was the beginning of Mr. Salim’s strange ordeal in United States custody. It has been 13 years since he was tortured in a secret prison in Afghanistan run by the Central Intelligence Agency, a place he calls “The Darkness.” It has been eight years since he was released — no charges, no explanations — back into the world.

Even after so much time, Mr. Salim, 45, is struggling to move on. Suffering from depression and post-traumatic stress, according to a medical assessment, he is withdrawn and wary. He cannot talk about his experiences with his wife, who he says worries that the Americans will come back to snatch him. He is fearful of drawing too much attention at home in Stone Town in Zanzibar, Tanzania, concerned that his neighbors will think he is an American spy.

When he speaks, not in his native Swahili but in the English he learned from his jailers, Mr. Salim nearly whispers. “Many times now I feel like I have something heavy inside my body,” he said in an interview. “Sometimes I walk, and I walk, and I forget, I forget everything, I forget prison, The Darkness, everything. But it is always there. The Darkness comes.”

Mr. Salim was one of 39 men subjected to some of the C.I.A.’s most brutal techniques — beatings, hanging in chains, sleep deprivation and water dousing, which creates a sensation of drowning, even though interrogators had been denied permission to use that last tactic on him, according to a Senate Intelligence Committee investigation into the agency’s classified interrogation program.

In a series of recent interviews in Dubai, Mr. Salim described his incarceration by the C.I.A. and the United States military as a terrorism suspect. His account closely parallels those provided by other detainees, witnesses and court documents, and confirms details in the Senate report about his treatment.

Today, back in Stone Town, Mr. Salim is trying to support his family, though some of his attempts at jobs have not worked out. He now breeds pigeons, raising them for a local market. They are both his livelihood and his solace.

They help him, Mr. Salim said. They quiet his mind.

A Life Interrupted

Exactly why Mr. Salim fell into American hands remains murky; leaks to the press at the time of his capture suggested that intelligence officials suspected he had links to Al Qaeda, but the C.I.A. has never publicly disclosed the reasons. An agency spokesman declined to comment for this article.

Mr. Salim had been drifting into a nomadic life in one of the world’s poorest regions, where the C.I.A. after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks had promised allies cash rewards for terrorism suspects. Governments and warlords turned over hundreds of men to the United States, in many cases with little evidence of wrongdoing.

Mr. Salim grew up on Africa’s eastern edges, but from boy to man never quite found himself. One of eight children in a family in Stone Town, a historic district of Zanzibar City, he apprenticed on the local fishing piers, then joined the crews going out for kingfish and barracuda in the Indian Ocean.

He dropped out of school after ninth or 10th grade and headed for Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s largest city, where he worked in a clothing shop. He moved a few years later to Mombasa, on Kenya’s coast, where he ferried cargos of dried fish, rice and oil with a crew of two.

Then the outside world intruded. In August 1998, Qaeda suicide truck bombers blew up the United States Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. Mr. Salim said a man whose boat he used for the cargo runs was suspected of involvement in the plot. (Mr. Salim said that while he was in prison, American officials told him that the man had died, but he knows no other details.) The boat was soon seized by a Somali pirate, he said.

Mr. Salim moved on to Kismayu, a Somali port town, and was hired as a harbor pilot. It was a good job, maybe too good for a foreigner with no ties to Somalia’s powerful clans and militias. “You had to pay off militias every time you moved a ship,” he said. “The clans were trouble, so I left.”

By 2000, he was sleeping in a mosque and begging on the streets of Mogadishu, the Somali capital. Eventually, a shop owner offered him odd jobs and work as a driver for him and his sister, who Mr. Salim said worked for Mohammed Dheere, a Somali warlord.

In March 2003, Mr. Salim was driving his employer through the capital when they pulled over to help a stalled vehicle. Suddenly, three gunmen appeared, dragged Mr. Salim out and started beating him, he said. He got away, but the men found him at the hospital where Mr. Salim’s boss had taken him.

The men said they worked for Mr. Dheere, and they claimed he owed the warlord money, Mr. Salim recounted. “I said no, but they kept saying, ‘You stole money from Mohammed Dheere.’”

The men drove him to a small airport outside the city. The Americans were waiting.

Bryan Denton for The New York Times: Mr. Salim shopping for pigeons in Johannesburg. He breeds and sells exotic varieties back home in Tanzania.

Hanging in Chains

They asked him over and over about his appearance, Mr. Salim said. “They said: ‘You are not Suleiman. You changed your face.’ I say: ‘Go to Tanzania. Go see my mother and take a picture of me.’”

He was turned over to the Kenyan authorities, who flew him to Nairobi. But after questioning him, the Kenyans sent him back to Somalia and the Americans. (Kenyan officials did not respond to a request for comment about Mr. Salim’s case.)

This time the Americans kept him. News accounts, including an article in The New York Times, soon appeared quoting United States and Kenyan officials describing the capture of a Qaeda operative from Yemen identified as Suleiman Abdalla Salim Hemed, who was wanted in connection with the 1998 embassy bombings. Mr. Salim said he never used the name Hemed and had nothing to do with Al Qaeda or terrorism.

The news reports also said Mr. Dheere, who died in 2012, had agreed to hunt down suspects, including the man identified in the press as Mr. Hemed, for the C.I.A. in return for money.

From Somalia, the C.I.A. flew Mr. Salim to a United States base in Djibouti. He was blindfolded and stripped, and an object was inserted in his rectum while the Americans photographed him, according to court documents. Just before he left Djibouti, Mr. Salim recalled, one of the captors told him that he was going to the “prison of the pharaohs.”

He was flown to Afghanistan, not Egypt as he guessed from what his captor said, and taken to the pitch-black, stinking and cavernous building that Mr. Salim calls The Darkness.

Music blasted nearly 24 hours a day while he was chained in solitary confinement so dark that he could not see the shackles on his arms or the walls of his cell. He said he could no longer listen to any of the songs that were on the prison playlist.

The Americans routinely hauled him from his cell to a room where, he said, they hanged him from chains, once for two days. They wrapped a collar around his neck and pulled it to slam him against a wall, he said. And they shaved his head, laid him on a plastic tarp and poured gallons of ice water on him, inducing a feeling of drowning.

“A guy says to me, ‘Here the rain doesn’t finish,’” Mr. Salim recalled. Several men wrapped him in the tarp and kicked him “many times, many times,” he added. At one point, a cast that a prison doctor had put on his hand — a finger had been broken by the Somali gunmen — became waterlogged. The doctor cut it off, and the water dousing continued.

Mr. Salim described other grisly practices by his jailers: placing him in a coffin-like box, his arms stretched and chained, on top of cleaning chemicals; strapping him to a gurney and injecting him with drugs that made him woozy; bringing dogs into a room to threaten him.

The 2014 Senate Intelligence Committee report noted that Mr. Salim was one of at least six detainees in 2003 who were “stripped and shackled nude, placed in the standing position for sleep deprivation, or subjected to other C.I.A. enhanced interrogation techniques.” The report said officials at C.I.A. headquarters had approved the use of some of the harsh tactics against Mr. Salim, but rejected interrogators’ requests for water dousing.

While 39 men endured the enhanced techniques, they were among at least 119 captives who went through the C.I.A.’s network of secret prisons. Many were later released without charges. A quarter were men who were picked up by mistake or on evidence that proved unreliable, a Senate inquiry later found. Others were low-level militants; some were suspected terrorist leaders, including accused plotters of the Sept. 11 attacks.

Mr. Salim said the interrogators had repeatedly questioned him about his ties in Kenya and Somalia. Among other things, he said, they claimed that he had falsified cargo documents on his boat, apparently to hide supplies for terrorists.

“They always asked the same questions. I say I don’t know. They say, ‘You know.’ Same question, same answer, and two guys would beat you, and same question, and they beat you.”

Desperate, Mr. Salim decided that suicide was his only escape. He hoarded the ibuprofen pills he sometimes was given, hiding them in the waistband of his pants. When he thought he had enough — 26 tablets — he tried to take them all at once. A guard, probably alerted by images from a video camera in the cell, rushed in and stopped Mr. Salim just as he began swallowing.

As he recounted the episode to a reporter, Mr. Salim began to cry uncontrollably, placed his arm across his face and rushed from the hotel room. Two days passed before he agreed to finish telling his story.

Five weeks after arriving in Afghanistan, Mr. Salim said, he was moved to the “Salt Pit,” a secret underground C.I.A. prison. Mr. Salim, who was blindfolded while being transferred, said that he did not travel far. The available evidence suggests that The Darkness was most likely a different section of the same facility.

Conditions improved slightly, though Mr. Salim was still interrogated regularly. “Every day questions: ‘You know him? You know him?’”

After 14 months, the C.I.A. in July 2004 handed Mr. Salim over to the United States military, which moved him to Bagram prison, outside Kabul. The young guards there nicknamed him Snoop because of his resemblance to the rapper Snoop Dogg.

The military held him for four more years. “Many times, they would say, ‘We know you are innocent,’” Mr. Salim said, referring to American personnel at the prison. “And many times they said that ‘you can go home, but it will take time.’ But they didn’t do it.”

In Bagram, he was kept in a large cage with as many as 22 other prisoners. Pigeons flew in and out of the large, drafty prison. “I remember one flew in, and was just outside our cage,” he said. “I was thinking, the pigeon was free and I was in the cage.”

‘A Ghost Walking’

In August 2008, Mr. Salim was released. The United States military gave him a document stating that there were no charges against him and that he had been “determined to pose no threat to the United States Armed Forces or its interests in Afghanistan.”

The military freed him with no possessions save the long red trousers and top that were his prison uniform, and no place to go. Mr. Salim had to borrow ill-fitting clothes from an International Red Cross representative in Afghanistan, who arranged for him to fly home to Zanzibar. Mr. Salim has kept the too-small clothes from the Red Cross man ever since.

At the airport in Zanzibar, he was met by a half-dozen members of his family and Tanzanian security officials. “They asked me the same questions the Americans had always asked me,” he said. But after two days, the Tanzanian government left him alone, with no restrictions on his activities. Tanzanian officials did not respond to a request for comment on his case.

In late 2008 or early 2009, two F.B.I. agents came to Tanzania to check up on him, Mr. Salim said. One agent said he had a gift: a T-shirt that said “Hakuna Matata” — no worries — from “The Lion King.” Mr. Salim angrily tossed it back. An F.B.I. spokesman said he had no information about the episode.

Mr. Salim returned to the world a stranger. He had gotten married just two weeks before he was taken captive in Mogadishu, but his wife disappeared while he was gone and he could not find her.

Back in Stone Town, Mr. Salim found simple tasks difficult. He was depressed and experienced nightmares and flashbacks about his time in prison, he said. They felt so real that he could not understand what was happening to his mind.

His attempts to work proved frustrating. His sister offered to pay him to drive his niece to school, but he got lost on the first day. He wanted to go back to sea, but local fishermen thought they might get in trouble associating with him.

In 2009 or 2010, Mr. Salim went to Dar es Salaam seeking a license to become a merchant seaman, but he did not pass the test. He briefly worked for a cargo shipping company in Japan, but he said that loading containers hurt his back, already injured in prison.

He listed other chronic physical problems from his time in custody: headaches, neck and shoulder pain, and severe gastrointestinal problems, common among detainees. Without a job, he lived with his mother and his sister at different times, humiliated that he was having so much trouble supporting himself.

In 2010, Dr. Sondra Crosby of the Boston University School of Medicine, a physician, a Navy reservist and an expert on torture, was asked by Physicians for Human Rights, a New York-based group, to evaluate Mr. Salim.

She was shocked by what she found. Mr. Salim, who is 6-foot-2, was emaciated “like a skeleton,” Dr. Crosby said in an interview. In her assessment, she wrote that “he is plagued by profound distress, inability to eat and inability to sleep.”

“He describes himself as a ghost walking around the town,” she added. She noted other symptoms: flashbacks, short- and long-term memory loss, distress at seeing anyone in a military uniform, hopelessness about the future and a strong avoidance of noise. “He reports that his head feels empty — like an empty box,” she said.

Dr. Crosby concluded that Mr. Salim showed many symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and major depression. He appears, she wrote, “to have suffered severe and lasting physical and psychological injuries as a result of his arrest and incarceration by U.S. forces.”

He is now a plaintiff in a lawsuit against two C.I.A. contractors who helped devise and run the brutal interrogation program of which he was a part. “I want the people who did this to be judged,” he said.

Mr. Salim remarried and has a 5-year-old daughter, but he finds it impossible to talk to his wife about what happened to him, or how it still haunts him. He says others around him do not understand what he went through.

He lives in a three-room house owned by a relative in a poor neighborhood outside Stone Town. Until recently, he made some money by taking tourists fishing on a boat owned by his brother-in-law. But it was swamped in a storm several months ago.

Mr. Salim’s pigeon coop in Zanzibar. It is larger than most of the cells in which the Americans kept him.

In the yard outside his house, he built a block and wire pigeon cage, 26 feet by 10 feet, larger than most of the cells in which the Americans kept him. When he needs to be alone, he goes there.

“I like to sit with the pigeons. I like to get away from people,” Mr. Salim said. “I sit there a long time.”

Where Even Nightmares Are Classified: Psychiatric Care at Guantánamo

Where Even Nightmares Are Classified: Psychiatric Care at Guantánamo

Secrecy, mistrust and the shadow of interrogation at the American prison limited doctors’ ability to treat mental illness among detainees.

By Sheri Fink, Originally published by The New York Times on November 12, 2016

A guard tower at a now-empty detention block at Guantánamo Bay. The prison, where nearly 800 men were held over the years, now has 60 detainees.

Every day when Lt. Cmdr. Shay Rosecrans crossed into the military detention center at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, she tucked her medical school class ring into her bra, covered the name on her uniform with tape and hid her necklace under her T-shirt, especially if she was wearing a cross.

She tried to block out thoughts of her 4-year-old daughter. Dr. Rosecrans, a Navy psychiatrist, had been warned not to speak about her family or display anything personal, clues that might allow a terrorism suspect to identify her.

Patients called her “torture bitch,” spat at her co-workers and shouted death threats, she said. One hurled a cup of urine, feces and other fluids at a psychologist working with her. Even interviewing prisoners to assess their mental health set off recriminations and claims that she was torturing them. “What would your Jesus think?” they demanded.

Dr. Rosecrans, now retired from the Navy, led one of the mental health teams assigned to care for detainees at the island prison over the past 15 years. Some prisoners had arrived disturbed — traumatized adolescents hauled in from the battlefield, unstable adults who disrupted the cellblocks. Others, facing indefinite confinement, struggled with despair.

Then there were prisoners who had developed symptoms including hallucinations, nightmares, anxiety or depression after undergoing brutal interrogations at the hands of Americans who were advised by other health personnel.

At Guantánamo, a willful blindness to the consequences emerged. Those equipped to diagnose, document and treat the effects — psychiatrists, psychologists and mental health teams — were often unaware of what had happened.

Sometimes by instruction and sometimes by choice, they typically did not ask what the prisoners had experienced in interrogations, current and former military doctors said. That compromised care, according to outside physicians working with legal defense teams, previously undisclosed medical records and court filings.

Dozens of men who underwent agonizing treatment in secret C.I.A. prisons or at Guantánamo were left with psychological problems that persisted for years, despite government lawyers’ assurances that the practices did not constitute torture and would cause no lasting harm, The New York Times has reported. Some men should never have been held, government investigators concluded. President-elect Donald J. Trump declared during his campaign that he would bring back banned interrogation tactics, including waterboarding, and authorize others that were “much worse.”

In recent interviews, more than two dozen military medical personnel who served or consulted at Guantánamo provided the most detailed account to date of mental health care there. Almost from the start, the shadow of interrogation and mutual suspicion tainted the mission of those treating prisoners. That limited their effectiveness for years to come.

Psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses and technicians received little training for the assignment and, they said, felt unprepared to tend to men they were told were “the worst of the worst.” Doctors felt pushed to cross ethical boundaries, and were warned that their actions, at an institution roiled by detainees’ organized resistance, could have political and national security implications.

Rotations lasted only three to nine months, making it difficult to establish rapport. In a field that requires intimacy, the psychiatrists and their teams long used pseudonyms like Major Psych, Dr. Crocodile, Superman and Big Momma, and referred to patients by serial numbers, not names. They frequently had to speak through fences or slits in cell doors, using interpreters who also worked with interrogators.

Wary patients often declined to talk to the mental health teams. (“Detainee refused to interact,” medical records note repeatedly.) At a place so shrouded in secrecy that for years any information learned from a detainee was to be treated as classified, what went on in interrogations “was completely restricted territory,” said Karen Thurman, a Navy commander, now retired, who served as a psychiatric nurse practitioner at Guantánamo. “‘How did it go?’” Or “‘Did they hit you?’ We were not allowed to ask that,” she said.

Dr. Rosecrans said she held back on such questions when she was there in 2004, not suspecting abuse and feeling constrained by the prison environment. “From a surgical perspective, you never open up a wound you cannot close,” she said. “Unless you have months, years, to help this person and help them get out of this hole, why would you ever do this?”

The United States military defends the quality of mental health care at Guantánamo as humane and appropriate. Detainees, human rights groups and doctors consulting for defense teams offer more critical assessments, describing it as negligent or ineffective in many cases.

Those who served at the prison, most of whom had never spoken publicly before, said they had helped their patients and had done the best they could. Given the circumstances, many focused on the most basic of duties.

“My goal was to keep everyone alive,” Dr. Rosecrans said.

“We tried to keep the water as smooth as possible,” Ms. Thurman said.

“My job was to keep them going,” said Andy Davidson, a Navy captain, now retired, and psychologist.

Conflicted Care

When Dr. Rosecrans worked briefly at the Navy’s hospital at Guantánamo as a young psychiatrist in 1999, it was a sleepy assignment. She saw only a few outpatients each week, and there was no psychiatric ward on the base, which was being downsized.

But after Al Qaeda’s 2001 terror attacks on New York and the Pentagon, and the subsequent American-led invasion of Afghanistan, detainees began pouring into the island in early 2002 — airplane loads of 20 to 30 men in shackles and blacked-out goggles. “We were seeing prisoners arriving with mental problems,” said Capt. Albert Shimkus, then the hospital’s commanding officer.

There were no clear protocols for treating patients considered to be “enemy combatants,” rather than prisoners of war, said Captain Shimkus, who is now retired. But he set out, with the tacit support of his commanders, to provide a level of care equivalent to that for American service members. He transformed a cellblock into a spartan inpatient unit for up to 20 patients and brought in Navy psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses and technicians to be available around the clock.

Many of them had little or no predeployment training, experience working in a detention facility or familiarity with the captives’ languages, cultures or religious beliefs. They soon heard talk of the threat the prisoners posed.

“The crew that was there before us scared the heck out of us,” said Dr. Christopher Kowalsky, who as a Navy captain led the mental health unit in 2004. He and Dr. Rosecrans said colleagues had admonished them for getting too close to patients. “‘Don’t forget they’re criminals,’” she was told.

Those arriving in later years attended a training program at a military base in Washington State. “You heard all these things about how terrible they are: Not only will they gouge your eyes out, but they’ll somehow tell their cohorts to go after your family,” said Daniel Lakemacher, who served as a Navy psychiatric technician. “I became extremely hateful and spiteful.”

Peering through small openings in cell doors, he and other technicians handed out medications, watched prisoners swallow them and ran through a checklist of safety questions — “Are you having thoughts of hurting yourself?” “Are you seeing things that aren’t there?” — through interpreters or English-speaking detainees in nearby cells. (“Talk about confidentiality!” Dr. Davidson said. “It’s just a whole other set of rules.”)

Conflicts arose between health professionals aiding interrogators and those trying to provide care. Army psychologists working with military intelligence teams showed up in 2002 and asked to be credentialed to treat detainees. “I said no, because they were there for interrogations,” Captain Shimkus said.

In June of that year, Maj. Paul Burney, an Army psychiatrist, and Maj. John Leso, an Army psychologist, both of whom had deployed to Guantánamo to tend to the troops, instead were assigned to devise interrogation techniques. In a memo, they listed escalating pressure tactics, including extended isolation, 20-hour interrogations, painful stress positions, yelling, hooding, and manipulation of diet, environment and sleep.

But they also expressed caution. “Physical and/or emotional harm from the above techniques may emerge months or even years after their use,” the two men warned in their memo, later excerpted in a Senate Armed Services Committee report. They added that the most effective interrogation strategy was developing a bond.

A version of the memo, stripped of its warnings, reached Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld. In December 2002, he approved many of the methods for Guantánamo, some of them similar to the “enhanced interrogation techniques” used by the C.I.A. at secret prisons overseas. After objections from military lawyers, he made some modifications but gave commanders license to use 24 techniques. Some of them later migrated to military prisons in Afghanistan and Iraq, including Abu Ghraib, where they morphed into horrific abuses.

“I think it was the absolute wrong way to proceed,” Dr. Burney, who has not previously commented publicly, said of the approved techniques. “I so wish I could go back and do things differently.”

He and Dr. Leso created the Behavioral Science Consultation Team, or BSCT (pronounced “biscuit”), to advise and sometimes rein in military interrogators, many of them young enlisted soldiers with little experience even interviewing people. The interrogators subjected some detainees at Guantánamo to loud music, strobe lights, cold temperatures, isolation, painful shackling, threats against family members and prolonged sleep deprivation, according to the Justice Department’s inspector general.

The government has never quantified how many prisoners underwent that treatment. In four cases, military leaders approved even harsher interrogation plans. At least two were carried out.

Dr. Burney said he and Dr. Leso took turns observing the questioning in 2002 of Mohammed al-Qahtani, who was accused of being an intended hijacker in the Sept. 11 attacks and, it later emerged, had a history of psychosis. Among other things, he was menaced with military dogs, draped in women’s underwear, injected with intravenous fluids to make him urinate on himself, put on a leash and forced to bark like a dog, and interrogated for 18 to 20 hours at least 48 times, government investigators found.

Mr. Qahtani was led to believe that he might die if he did not cooperate, Dr. Burney said in a statement provided to the Senate committee. When Mr. Qahtani asked for a doctor to relieve psychological symptoms, the interrogators instead performed an exorcism for “jinns” — supernatural creatures that he believed caused his problems.

In 2009, a Department of Defense official overseeing military commissions refused to prosecute Mr. Qahtani, telling The Washington Post that his mistreatment had amounted to torture. In 2012, a federal judge found Mr. Qahtani incompetent to help challenge his detention.

Those providing mental health care at Guantánamo quickly aroused the suspicions of some prisoners, who called them devils, criminals and dogs.

“Nobody trusted them,” said Lutfi bin Ali, a Tunisian who was sent to Guantánamo after being subjected to harsh conditions at what he described as an American jail overseas. “There was skepticism that they were psychiatrists and that they were trying to help us,” he said by phone from Kazakhstan, where he was transferred to in 2014. He still suffers intermittently from depression.

Dr. Davidson, who treated prisoners at Guantánamo during part of 2003, recalled the hostility. “I can tell the guy until the cows come home, ‘Hey, I’m just here for mental health,’” he said. “‘No, you’re not,’” he imagined the patient thinking, “‘you’re the enemy.’”

One day on the cellblocks, Dr. Rosecrans heard detainees warn others that she could not be trusted. “Some of my patients hated me,” she said. “They saw me as a representative of the government.”

She and other clinicians who felt uncomfortable walking around the prison grounds relied mostly on guards to identify detainees who needed help and to take them to an examination room, where they would be chained to the floor.

Interpreters were in such short supply at times that they worked with both the mental health teams and the interrogators. “See where that could be a problem?” Dr. Rosecrans asked.

All of that fed the conviction among detainees that information about their mental health was being exploited by interrogators. “If you complain about your weak point to a doctor, they told that to the interrogators,” said Younous Chekkouri, a Moroccan, now released.

He recalled seeing one psychologist working alongside interrogators and then treating detainees at the prison. Only years later, he said, did he feel he could trust certain psychiatrists there. He said he still suffered from flashbacks and anxiety after being beaten at a military prison in Afghanistan, and kept in isolation and shown execution photos at Guantánamo.

Captain Shimkus, who oversaw patient care, said some clinicians had expressed concerns about the blurred lines between medical care and interrogation. He said he had allowed one psychiatrist, who was disturbed by the lack of confidentiality, to temporarily recuse himself from caring for patients because the doctor believed “the patient-physician relationship was compromised.”

The United States Southern Command told health care providers at Guantánamo in 2002 that their communications with patients were “not confidential.” At first, interrogators had direct access to medical information. Then, the BSCT psychologists acted as liaisons.

They regularly read patient records in the psychiatry ward, said Dr. Frances Stewart, a retired Navy captain and psychiatrist who treated detainees in 2003 and 2004. As a consequence, she said, “I tried to document just the things that really needed to be documented — things like ‘the patient has a headache; we treated it with Tylenol’ — not anything terribly sensitive. It was not a perfect solution, but it was probably the best solution I could come up with at the time.”

Dr. Kowalsky, a psychiatrist, said patients had begged him not to record their diagnoses. “They’re going to use that,” some detainees told him.

The International Committee of the Red Cross, during a June 2004 visit, documented the same complaint. Medical files, the group said in confidential remarks revealed in The Times, were regularly used to devise strategies for interrogations that it called “tantamount to torture.” Interrogators’ access to medical records was a “flagrant violation of medical ethics.” The Pentagon disputed that the records were used to harm detainees.

Dr. Kowalsky said he clashed with a BSCT psychologist, Diane Zierhoffer, who showed up in the psychiatric unit to look at patient records in 2004. (Dr. Zierhoffer, in an email, said her intent in accessing records had been to “ensure health care was not interfered with.”)

“We’re here to help people,” Dr. Kowalsky recalled once telling her.

“We’re here to protect our country,” he said she had responded, later asking: “Whose side are you on?”

They Didn’t Ask

Sometimes it wasn’t clear what was forbidden or what had just become practice, but it had the same effect: Psychiatrists and psychologists said they had almost never asked a detainee about his treatment by interrogators, either at Guantánamo or at the C.I.A. prisons.

Mohamedou Ould Slahi, who was released to his native Mauritania in October after 14 years at Guantánamo, told a doctor on his legal team that military mental health providers did not ask him about possible mistreatment, according to a sealed court report obtained by The Times. Mr. Slahi did not volunteer the information because he was afraid of retaliation, he wrote in his prison memoir, “Guantánamo Diary.”

Mr. Slahi endured some of the most brutal treatment there. Investigations by the Army, the Justice Department and the Senate largely corroborated his account of being deprived of sleep; beaten; shackled in painful positions; forced to drink large amounts of water; isolated in darkness and exposed to extreme temperatures; stripped and soaked in cold water; told that his mother might be sent to Guantánamo; and sexually assaulted by female interrogators.

Decades earlier, he had joined the insurgency against the Soviet-backed government in Afghanistan, a cause supported by the United States. In 1991, he attended a Qaeda training camp, and was later suspected of recruiting for the terrorist group. A federal judge ordered him freed in 2010 for lack of evidence, but an appeals court overturned the decision. In July, a military review board recommended his transfer.

Prison medical records show that Mr. Slahi, a computer specialist with no history of mental illness, received anti-anxiety medicine, antidepressants, sleeping pills and psychotherapy, and that he had recurring nightmares of being tortured in the years after his ordeal.

Dr. Vincent Iacopino, a civilian physician who evaluated Mr. Slahi in 2007 for his defense team, criticized psychologists and psychiatrists at Guantánamo for failing “to adequately pursue the obvious possibility of PTSD,” or post-traumatic stress disorder, linked to severe physical and mental harm, the records show. Dr. Iacopino said military doctors had medicated Mr. Slahi for his symptoms instead of trying to treat his underlying disorder, which had “profound long-term and debilitating psychological effects.” Last year, one of Mr. Slahi’s lawyers described him as “damaged.”

He was one of nearly 800 men incarcerated at Guantánamo over the years and one of several whose confessions were tainted by mistreatment and disallowed as evidence by the United States. Many prisoners were Qaeda and Taliban foot soldiers later deemed to pose little threat. Some were victims of mistaken identity or held on flimsy evidence.

Dr. Burney, who assisted the interrogators, said he had seen many detainees’ files. “It seemed like there wasn’t a whole lot of evidence about anything for a whole lot of those folks,” he said.

After the C.I.A.’s secret prisons were shut in 2006, Guantánamo took in more than a dozen so-called high-value detainees, including those accused of plotting the Sept. 11 attacks. Some doctors at Guantánamo said they had been instructed, in briefings or by colleagues, not to ask these former “black site” prisoners about what had happened there. Virtually everything about these captives was classified until a Senate Intelligence Committee report in 2014 disclosed grisly details about torture.

“You just weren’t allowed to talk about those things, even with them,” said Dr. Michael Fahey Traver, an Army psychiatrist at Guantánamo in 2013 and 2014. He was assigned to treat only high-value detainees kept in Camp 7, Guantánamo’s most restricted area, so that he did not inadvertently pass sensitive information to other prisoners.

If a detainee raised the subject of his prior treatment, Dr. Traver was to redirect the conversation, he said his predecessor had told him. Among his patients were Ramzi bin al-Shibh, accused of helping plot the Sept. 11 attacks, and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, who was charged in the 2000 bombing of the American destroyer Cole and endured some of the C.I.A.’s most extreme interrogation techniques, including waterboarding.

At the request of prosecutors, a military psychiatrist and two military psychologists went to Guantánamo in 2013 to assess Mr. Nashiri’s competency to assist in his defense. The panel concluded that, while competent, he suffered from PTSD and major depression.

The military commission trying Mr. Nashiri held a hearing in 2014 on the adequacy of his mental health care. Shortly before the hearing, Dr. Traver removed a previous diagnosis by another Guantánamo psychiatrist that Mr. Nashiri had PTSD. “I didn’t think he met that diagnosis,” Dr. Traver said in an interview.

Dr. Sondra Crosby, an expert on torture who consulted for Mr. Nashiri’s defense, disagreed. Dr. Crosby, an internist, said his treatment was inadequate. “He suffers chronic nightmares,” she testified in an affidavit, which “directly relate to the specific physical, emotional and sexual torture inflicted upon Mr. al-Nashiri while in U.S. custody.” The content of his nightmares, she wrote, was classified.

The commission judge, citing a Supreme Court ruling that prisons must provide health care, found insufficient evidence of “deliberate indifference” to his medical needs.

What went on after prisoners were summoned for interrogations at Guantánamo was mostly a mystery to the mental health personnel, some of them said. Even when patients returned from sessions “looking terrible,” said Mr. Lakemacher, the former psychiatric technician, “that was not to be addressed.” (After his deployment, Mr. Lakemacher said, he regretted taking part in what he came to consider the unjust, indefinite detention of prisoners. He later was discharged from the Navy as a conscientious objector.)

Some doctors, on their own, shied away from the subject of interrogation tactics. “I didn’t want to get near that stuff,” Dr. Rosecrans said. “Men would say, ‘When I got here, they treated me like a dog,’” or that they were humiliated, she said, but she refrained from inquiring, in part, “to preserve their dignity.”

When detainees claimed to have been tortured or maltreated, “you didn’t know if it was true or not,” she said.

“Is it PTSD, or is it delusional disorder?” she said, adding, “I was in such a vacuum.”

But Dr. Rosecrans had little reason to suspect abusive treatment, she said, because some prisoners seemed eager to go to interrogation sessions, which they called “reservations.” Interrogators, working in trailers separate from the structures where detainees were housed, doled out rewards like snack food or magazines; speaking with them broke the boredom for detainees.

“It was a way to get out of their cell,” said Ms. Thurman, the nurse practitioner. “They’d do anything, I think, to do something different for the day.”

Dr. Stewart, the Navy captain who treated detainees in 2003 and 2004, said she had never noticed any men in distress after returning from interrogations. But she typically did not ask what had happened there or try to focus on trauma in therapy, she said. “I didn’t want to stir up anything that might make things worse,” she said.

PTSD, generally thought to be the most common psychiatric illness resulting from torture, was rarely diagnosed at Guantánamo. Dr. Rosecrans and other doctors who served there said the diagnosis did not matter because they could still treat the symptoms, like depression, anxiety or insomnia.