Brain Wars: How the Military is Failing its Wounded

This comprehensive multimedia investigation delves into the ramifications of the signature wound of today’s wars: traumatic brain injury (TBI). Originally published by ProPublica and NPR in 2010.

Brain Injuries Remain undiagnosed in Thousands of Soldiers

WASHINGTON, D.C.--The military medical system is failing to diagnose brain injuries in troops who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, many of whom receive little or no treatment for lingering health problems, an investigation by ProPublica and NPR has found.

So-called mild traumatic brain injury has been called one of the wars' signature wounds. Shock waves from roadside bombs can ripple through soldiers' brains, causing damage that sometimes leaves no visible scars but may cause lasting mental and physical harm.

Officially, military figures say about 115,000 troops have suffered mild traumatic brain injuries since the wars began. But top Army officials acknowledged in interviews that those statistics likely understate the true toll. Tens of thousands of troops with such wounds have gone uncounted, according to unpublished military research obtained by ProPublica and NPR.

"When someone's missing a limb, you can see that," said Sgt. William Fraas, a Bronze Star recipient who survived several roadside blasts in Iraq. He can no longer drive, or remember simple lists of jobs to do around the house. "When someone has a brain injury, you can't see it, but it's still serious."

In 2007, under enormous public pressure, military leaders pledged to fix problems in diagnosing and treating brain injuries. Yet despite the hundreds of millions of dollars pumped into the effort since then, critical parts of this promise remain unfulfilled.

Over four months, we examined government records, previously undisclosed studies, and private correspondence between senior medical officials. We conducted interviews with scores of soldiers, experts and military leaders.

Among our findings:

- From the battlefield to the home front, the military's doctors and screening systems routinely miss brain trauma in soldiers. One of its tests fails to catch as many as 40 percent of concussions, a recent unpublished study concluded. A second exam, on which the Pentagon has spent millions, yields results that top medical officials call about as reliable as a coin flip.

- Even when military doctors diagnose head injuries, that information often doesn't make it into soldiers' permanent medical files. Handheld medical devices designed to transmit data have failed in the austere terrain of the war zones. Paper records from Iraq and Afghanistan have been lost, burned or abandoned in warehouses, officials say, when no one knew where to ship them.

- Without diagnosis and official documentation, soldiers with head wounds have had to battle for appropriate treatment. Some received psychotropic drugs instead of rehabilitative therapy that could help retrain their brains. Others say they have received no treatment at all, or have been branded as malingerers.

In the civilian world, there is growing consensus about the danger of ignoring head trauma: Athletes and car accident victims are routinely tested for brain injuries and are restricted from activities that could result in further blows to the head.

But the military continues to overlook similarly wounded soldiers, a reflection of ambivalence about these wounds at the highest levels, our reporting shows. Some senior Army medical officers remain skeptical that mild traumatic brain injuries are responsible for soldiers' troubles with memory, concentration and mental focus.

Civilian research shows that an estimated 5 percent to 15 percent of people with mild traumatic brain injury have persistent difficulty with such cognitive problems.

"It's obvious that we are significantly underestimating and underreporting the true burden of traumatic brain injury," said Maj. Remington Nevin, an Army epidemiologist who served in Afghanistan and has worked to improve documentation of TBIs and other brain injuries. "This is an issue which is causing real harm. And the senior levels of leadership that should be responsible for this issue either don't care, can't understand the problem due to lack of experience, or are so disengaged that they haven't fixed it."

When Lt. Gen. Eric Schoomaker, the Army's most senior medical officer, learned that NPR and ProPublica were asking questions about the military's handling of traumatic brain injuries, he initially instructed local medical commanders not to speak to us.

"We have some obvious vulnerabilities here as we have worked to better understand the nature of our soldiers' injuries and to manage them in a standardized fashion," he wrote in an e-mail sent to bases across the country. "I do not want any more interviews at a local level."

When confronted with the findings later, however, he acknowledged shortcomings in the military's diagnosing and documenting of head traumas.

"We still have a big problem and I readily admit it," said Schoomaker, the Army's surgeon general. "That is a black hole of information that we need to have closed."

Brig. Gen. Loree Sutton, who oversees brain injury issues for the Pentagon, said the military had made great strides in improving attitudes towards the detection and treatment of traumatic brain injury.

The military is considering implementing a new policy to mandate the temporary removal from the battlefield of soldiers exposed to nearby blasts. Later this year, the Pentagon expects to open a cutting-edge center for brain and psychological injuries, which will treat about 500 soldiers annually.

"This journey of cultural transformation, it is a journey not for the faint of heart," Sutton said. "At the end of our journeys, at the end of our travels, what we must ensure is, we must ensure that we have consistent standards of excellence across the board. Are we there yet? Of course we're not there yet."

Soldiers like Michelle Dyarman wonder what's taking so long. Dyarman, a former major in the Army reserves, was involved in two roadside bomb attacks and a Humvee accident in Iraq in 2005.

Today, the former dean's list student struggles to read a newspaper article. She has pounding headaches. She has trouble remembering the address of the farmhouse where she grew up in the hills of central Pennsylvania.

For years, Dyarman fought with Army doctors who did not believe that she was suffering lasting effects from the blows to her head. Instead, they diagnosed her with an array of maladies from a headache syndrome to a mood disorder.

"One of the first things you learn as a soldier is that you never leave a man behind," said Dyarman, 45. "I was left behind."

In 2008, after Dyarman retired from the Army, Veterans Affairs doctors linked her cognitive problems to her head traumas.

Dyarman has returned to her civilian job inspecting radiological devices for the state, but colleagues say she turns in reports with lots of blanks; they cover for her.

Dyarman's 67-year-old father, John, looks after her at home, balancing her checkbook, reminding her to turn the oven on before cooking. The joyful, bright child he raised, the first in the family to attend college, is gone, forever gone.

"It hurts me, too," he said, growing upset as he spoke. "That's my daughter sitting there, all screwed up. She's not the kid she was."

Walkie Talkies

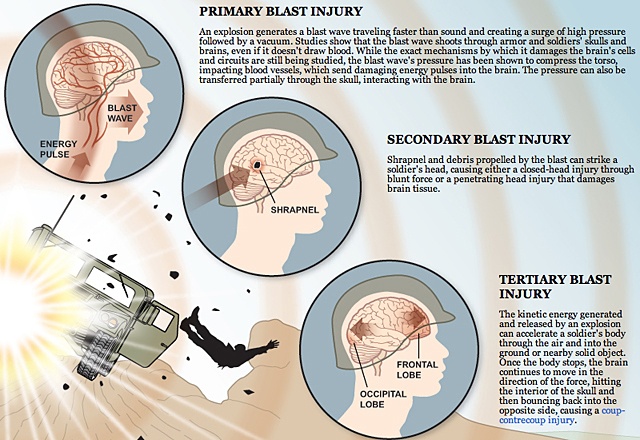

Better armor and battlefield medicine mean troops survive explosions that would have killed an earlier generation. But blast waves from roadside bombs, insurgents' most common weapon, can still damage the brain.

The shock waves can pass through helmets, skulls and through the brain, damaging its cells and circuits in ways that are still not fully understood. Secondary trauma can follow, such as sending a soldier tumbling inside a vehicle or hurling into a wall, shaking the brain against the skull.

Not all brain injuries are alike. Doctors classify them as moderate or severe if patients are knocked unconscious for more than 30 minutes. The signs of trauma are obvious in these cases and medical scanning devices, like MRIs, can detect internal damage.

But the most common head injuries in Iraq and Afghanistan are so-called mild traumatic brain injuries. These are harder to detect. Scanning devices available on the battlefield typically don't show any damage. Recent studies suggest that breakdowns occur at the cellular level, with cell walls deteriorating and impeding normal chemical reactions.

Doctors debate how best to categorize and describe such injuries. Some say the term mild traumatic brain injury best describes what happens to the brain. Others prefer to use concussion, insisting the word carries less stigma than brain injury.

Whatever the description, most soldiers recover fully within weeks, military studies show. Headaches fade, mental fogs clear and they are back on the battlefield.

For a minority, however, mental and physical problems can persist for months or years. Nobody is sure how many soldiers who suffer mild traumatic brain injury will have long-term repercussions. Researchers call the 5 percent to 15 percent of civilians who endure persistent symptoms the "miserable minority."

A study published last year in the Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation found that, of the 900 soldiers in one battle-hardened Army brigade who suffered brain injuries, most of them mild, almost 40 percent reported having at least one symptom weeks or months later.

The long-term effects of mild traumatic brain injuries can be devastating, belying their name. Soldiers can endure a range of symptoms, from headaches, dizziness and vertigo to problems with memory and reasoning. Soldiers in the field may react more slowly. Once they go home, some commanders who led units across battlefields can no longer drive a car down the street. They can't understand a paragraph they have just read, or comprehend their children's homework. Fundamentally, they tell spouses and loved ones, they no longer think straight.

Such soldiers are sometimes called "walkie talkies" -- unlike comrades with missing limbs or severe head wounds, they can walk and talk. But the cognitive impairments they face can be severe.

"These are people who go on to live" with "a lifelong chronic disability," said Keith Cicerone, a leading researcher in the field. "It is going to be terrifically disruptive to their functioning."

An increasing number of brain-injury specialists say the best way to treat patients with lasting symptoms is to get them into cognitive rehabilitation therapy as soon as possible. That was the consensus recommendation of 50 civilian and military experts gathered by the Pentagon in 2009 to discuss how to treat soldiers.

Such therapy can retrain the brain to compensate for deficits in memory, decision-making and multitasking.

A soldier whose injuries are not diagnosed or documented misses out on the chance to get this level of care -- and the hope for recovery it offers, say veterans advocates, soldiers and their families.

"Talk is cheap. It is easy to say we honor our servicemen," said Cicerone, who has helped the military develop recommendations for appropriate treatments for soldiers with brain injuries. "I don't think the services that we are giving to those servicemen honors those servicemen."

Missing Records

The military's handling of traumatic brain injuries has drawn heated criticism before.

ABC News reporter Bob Woodruff chronicled the difficulties soldiers faced in getting treatment for head traumas after recovering from one himself, suffered in a 2006 roadside bombing in Iraq. The following year, a Washington Post series about substandard conditions at Walter Reed Army Medical Hospital described the plight of several soldiers with brain injuries.

Members of Congress responded by dedicating more than $1.7 billion to research and treatment of traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress, a psychological disorder common among soldiers returning from war. They passed a law requiring the military to test soldiers' cognitive functions before and after deployment so brain injuries wouldn't go undetected.

But leaders' zeal to improve care quickly encountered a host of obstacles. There was no agreement within the military on how to diagnose concussions, or even a standardized way to code such incidents on soldiers' medical records.

Good intentions banged up against the military's gung ho culture. To remain with comrades, soldiers often shake off blasts and ignore symptoms. Commanders sometimes ignore them, too, under pressure to keep soldiers in the field. Medics, overwhelmed with treating life-threatening injuries, may lack the time or training to recognize a concussion.

The NPR and ProPublica investigation, however, indicates that the military did little to overcome those battlefield hurdles. They waited for soldiers to seek medical attention, rather than actively seeking to evaluate those in blasts.

The military also has repeatedly bungled efforts to improve documentation of brain injuries, the investigation found.

Several senior medical officers said soldiers' paper records were often lost or destroyed, especially early in the wars. Some were archived in storage containers, then abandoned as medical units rotated out of the war zones.

Lt. Col. Mike Russell, the Army's senior neuropsychologist, said fellow medical officers told him stories of burning soldiers' records rather than leaving them in Iraq where anyone might find them.

"The reality is that for the first several years in Iraq everything was burned. If you were trying to dispose of something, you took it out and you put it in a burn pan and you burned it," said Russell, who served two tours in Iraq. "That's how things were done."

To improve recordkeeping, medics began using pricey handheld devices to track injuries electronically. But they often broke or were unable to connect with the military's stateside databases because of a lack of adequate Internet bandwidth, said Nevin, the Army epidemiologist.

"These systems simply were not designed for war the way we fight it," he said.

In 2007, Nevin began to warn higher-ups that information was being lost. His concerns were ignored, he said. While communications have improved in Iraq, Afghanistan remains a concern.

That same year, clinicians interviewed soldiers about whether they had suffered concussions for an unpublished Army analysis, which was reviewed by NPR and ProPublica. They found that the military files showed no record of concussions in more than 75 percent of soldiers who reported such injuries to the clinicians.

Nevin said that without documentation of wounds, soldiers could have trouble obtaining treatment, even when they report they can't think, or read, or comprehend instructions normally anymore.

Doctors might say, "there's no evidence you were in a blast," Nevin said. "I don't see it in your medical records. So stop complaining."

Problems documenting brain injuries continue.

Russell said that during a tour of Iraq last year, he examined five soldiers the day after they were injured in a January 2009 rocket attack. The medical staff had noted shrapnel injuries, but Russell said they failed to diagnose the soldiers' concussions.

The symptoms were "classic," Russell said. The soldiers had "dazed" expressions, and were slow to respond to questions.

"I found out several of them had significant gaps in their memory," Russell said. "It wasn't clear how long they were unconscious for, but the last thing they remember is they were playing video games. The next thing they remember, they are outside the trailer."

Another doctor told NPR and ProPublica of finding soldiers with undocumented mild traumatic brain injuries in Afghanistan as recently as February 2010.

"It's still happening, there's no doubt," said the military doctor, who did not want to be named for fear of retribution

Screened Out

After the Walter Reed scandal, the military instituted a series of screens to better identify service members with brain injuries. Soldiers take an exam before deploying to a war zone, another after a possible concussion in theater, and a third after returning home.

But each of these screens has proved to have critical flaws.

The military uses an exam called the Automated Neuropsychological Assessment Metrics, or ANAM, to establish a baseline for soldiers' cognitive abilities. The ANAM is composed of 29 separate tests that measure reaction times and reasoning capabilities. But the military, looking to streamline the process, decided to use only six of those tests.

Doubts immediately arose about the exam, which had never been scientifically validated. Schoomaker, the Army surgeon general, recently told Congress that the ANAM was "fraught with problems" and that "as a screening tool," it was "basically a coin flip."

Military clinicians have administered the exam to more than 580,000 soldiers, costing the military millions of dollars per year, but have accessed the results for diagnostic purposes only about 1,500 times.

Rep. Bill Pascrell Jr., D-N.J., who has led efforts to improve the treatment and study of brain injuries, accused the military of ignoring the Congressional directive.

"We are not doing service to our bravest," Pascrell said. "There needs to be a sense of urgency on this issue. We are not doing justice."

Once in theater, soldiers are supposed to take the Military Acute Concussion Evaluation, or MACE, to check for cognitive problems after blasts or other blows to the head.

But in interviews, soldiers said they frequently gamed the test, memorizing answers beforehand or getting tips from the medics who administer it.

Just last summer, Sgt. Victor Medina was leading a convoy in southern Iraq when a roadside bomb exploded. He was knocked unconscious for 20 minutes.

Afterwards, Medina had trouble following what other soldiers were saying. He began slurring his words. But he said the medic helped him to pass his MACE test, repeating questions until he answered them correctly.

"I wanted to be back with my soldiers," he said. "I didn't argue about it.".

Senior military officials said problems with the MACE were common knowledge.

"There's considerable evidence that people were being coached or just practicing," said Russell, the senior neuropsychologist. "They don't want to be sidelined for a concussion. They don't want to be taken out of play."

If cases of brain trauma get past the battlefield screen, a third test -- the post-deployment health assessment, or PDHA -- is supposed to catch them when soldiers return home.

But a recent study, as yet unpublished, shows this safety net may be failing, too.

When soldiers at Fort Carson, Colo., were given a more thorough exam bolstered by clinical interviews, researchers found that as many as 40 percent of them had mild traumatic brain injuries that the PDHA had missed.

In a 2007 e-mail, a senior military official bluntly acknowledged the shortcomings of PDHA exams, describing them as "coarse, high-level screening tools that are often applied in a suboptimal assembly line manner with little privacy" and "huge time constraints."

Col. Heidi Terrio, who carried out the Fort Carson study, said the military's screens must be improved.

"It's our belief that we need to document everyone who sustained a concussion," she said. "It's for the benefit of the Army and the benefit of the family and the soldier to get treatment right away."

Gen. Peter Chiarelli, the Army's second in command, acknowledged that the military has not made the progress it promised in diagnosing brain injuries.

"I have frustration about where we are on this particular problem," Chiarelli said.

Fundamentally, he said, soldiers, military officers and the public needed to take concussions seriously.

"We've got to change the culture of the Army. We've got to change the culture of society," he said, adding later, "We don't want to recognize things we can't see."

Skeptics

The shift Chiarelli envisions may be impossible without buy-in from senior military medical officials, some of whom are skeptical about the long-term harm caused by mild traumatic brain injuries.

One of Schoomaker's chief scientific advisors, retired Army psychiatrist Charles Hoge, has been openly critical of those who are predisposed to attribute symptoms like memory loss and concentration problems to mild traumatic brain injury.

In 2009, he wrote a opinion piece in the New England Journal of Medicine that said the "illusory demands of mild TBI" might wind up hobbling the military with high costs for unnecessary treatment. Recently, Hoge questioned the importance of even identifying mild traumatic brain injury accurately.

"What's the harm in missing the diagnosis of mTBI?" he wrote to a colleague in an April 2010 e-mail obtained by NPR and ProPublica. He said doctors could treat patients' symptoms regardless of their underlying cause.

In an interview, Hoge said, "I've been concerned about the potential for misdiagnosis, that symptoms are being attributed to mild traumatic brain injury when in fact they're caused by other" conditions. He noted that a study he conducted, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, "found that PTSD really was the driver of symptoms. That doesn't mean that mTBI isn't important. It is important. It's very important."

Other experts called Hoge's posture toward mild TBI troubling.

To be sure, brain injuries and PTSD sometimes share common symptoms and co-exist in soldiers, brought on by the same terrifying events. But treatments for the conditions differ, they said. A typical PTSD program, for instance, doesn't provide cognitive rehabilitation therapy or treat balance issues. Sleep medication given to someone with nightmares associated with PTSD might leave a brain-injured patient overly sedated, without having a therapeutic effect.

"I'm always concerned about people trivializing and minimizing concussion," said James Kelly, a leading researcher who now heads a cutting-edge Pentagon treatment center for traumatic brain injury. "You still have to get the diagnosis right. It does matter. If we lump everything together, we're going to miss the opportunity to treat people properly."

***

At her family farm outside Hanover, Pa., Michelle Dyarman has a large box overflowing with medical charts, letters and manila envelopes. They are the record of her fight over the past five years to get diagnosis and treatment for her traumatic brain injury.

After her last roadside blast in Baghdad, which killed two colleagues, Dyarman wound up at Walter Reed for treatment of post-traumatic stress.

Over the course of two and a half years, she received drugs for depression and nightmares. She got physical therapy for injuries to her back and neck. A rehabilitation specialist gave her a computer program to help improve her memory.

But it wasn't until she began talking with fellow patients that she heard the term mild traumatic brain injury. As she began to research her symptoms, she asked a neurologist whether the blasts might have damaged her brain.

Records show the neurologist dismissed the notion that Dyarman's "minor head concussions" were the source of her troubles, and said her symptoms were "likely substantially attributable" to PTSD and migraine headaches.

"It was disappointing," she said. "It felt like nobody cared."

When she was later given a diagnosis of traumatic brain injury by Veterans Affairs doctors, she said she felt vindicated, yet cheated all at once.

"I always put the military first, even before my family and friends. Now looking back, I wonder if I did the right thing," she said. "I served my country. Now what's my country doing for me?"

After Our Investigation, Pentagon Puts Its Spin on Brain Injuries

ProPublica and NPR reported today that the military is failing to diagnose soldiers who suffered brain injuries in Iraq and Afghanistan. It didn't take long to get a response. Soon after learning that the stories were about to air, the Pentagon's public affairs machine began circulating talking points on traumatic brain injuries2014just in case senior medical commanders weren't up to speed on what the military's been doing for troops with one of the wars' signature wounds.

The talking points, which we obtained and were sent to top Army officials, don't directly address the findings of our investigation. We found that the military's system has repeatedly overlooked soldiers with so-called mild traumatic brain injuries. These blast injuries, which some doctors call concussions, leave no visible scars but can cause lasting physical and mental harm in some cases. The Pentagon's official figures say about 115,000 soldiers have suffered a mild traumatic brain injury since the wars began. But we found that military doctors and screening tools routinely miss soldiers who have suffered mild traumatic brain injuries on the battlefield. Experts we interviewed and documents we obtained said the military's count may understate the true toll by tens of thousands of soldiers.

The talking points are upbeat. One says that the Department of Defense has the "world's best TBI medical care for our service members." Leading neuropsychologists and rehabilitation therapists have told us that's not true, however. They say the military doesn't always provide the kind of intensive cognitive rehabilitation therapy most experts recommend. The talking points also stressed that one military screen, called the ANAM, for Automated Neuropsychological Assessment Metrics, will be "utilized when soldiers come home to help measure the effects of any identified mild brain trauma that may have gone unnoticed or untreated."

But when we talked to the man who ran that program, he told us the ANAM was rarely used that way. Lt. Col. Mike Russell, the Army's senior neuropsychologist, said that more than 580,000 ANAM tests have been administered to soldiers before they deploy to the battlefield. But doctors have only used them about 1,500 times to diagnose soldiers after they've suffered a blow to the head.

The talking points tick off a number of initiatives the military has undertaken to better diagnose and treat the soldiers. But as we note in our stories, the problem is not the lack of initiatives, it's that nine years into the war, nobody at the Pentagon knows how big the problem is, nor how best to treat it. You can find the complete talking points memos and PowerPoint here.

Phone calls to the medical command's spokeswoman were not immediately returned.

At Fort Bliss, Brain Injury Treatments Can Be as Elusive as Diagnosis

A version of this story was aired on NPR's "All Things Considered." Listen to the audio broadcast below:

FORT BLISS, Texas -- At this rapidly expanding base along the U.S.-Mexico border, the military is racing to build new homes for 10,000 additional soldiers. Cranes stack prefabricated containers like children's blocks to erect barracks overnight. Bulldozers grind sagebrush desert into roads and runways.

Just down the street from the construction boom squats a tan, featureless building about the size of a convenience store. Completed nearly a year ago, it remains unopened, the doors locked.

Building 805 was supposed to house a clinic for traumatic brain injury, often called the signature wound of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Instead, it has become a symbol for soldiers here of what they call commanders' indifference to their problems.

"The system here has no mercy," said Sgt. Victor Medina, a decorated combat veteran who fought to receive treatment at Fort Bliss after suffering a brain injury during a roadside blast in Iraq last June. Since the explosion, Medina has had trouble reading, comprehending and doing simple tasks. "It's struggle after struggle."

Previously, ProPublica and NPR reported that the military has failed to diagnose brain injuries in troops who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. Mild traumatic brain injuries, which doctors also call concussions, do not leave visible scars but can cause lasting mental and physical problems.

At Fort Bliss, we found that even soldiers who are diagnosed with such injuries often do not receive the treatment they need.

Most specialists say it is critical for patients who show lingering effects from head trauma to get intensive therapy as soon as possible. In the civilian world, such therapy is increasingly seen as the best way to minimize permanent damage, helping to retrain the mind to compensate for deficits.

Yet brain-injured soldiers at Fort Bliss have had to wait weeks and sometimes months just to get appointments with doctors, medical records show. Many have received far less therapy than is typical at well-regarded civilian clinics. In some instances, Fort Bliss medical officers have suggested that the soldiers are malingerers or that the main root of their cognitive problems is psychological.

"Here you have all these soldiers looking for help, and it was just getting swept under the carpet," said Sgt. Brandon Sanford, 28, a dog handler who survived two roadside blasts in Iraq. Sanford endured a year of balance problems and mental fog before Fort Bliss officials sent him for cognitive therapy. "I served my country. I've got an injury to prove it."

It is impossible for civilians to know how Fort Bliss' care for brain-injured soldiers compares in quality or scale to that of other bases. Base officials would not give ProPublica and NPR data on how many soldiers are being treated there and the Pentagon would not provide this information for bases elsewhere.

Fort Bliss -- the third-largest base in the U.S. military and a vital nerve center for deploying and returning troops -- is supposed to be among the best. In 2007, the Pentagon designated it as one of 20 bases nationally that would develop augmented treatment programs for traumatic brain injury.

Yet while base commanders have spent more than $3 billion to expand and improve Fort Bliss over the past several years, they have directed just $5 million to facilities and clinicians to treat TBI. The program had no full-time director until October 2009. A neuropsychologist was hired only recently, after a two-year search.

Fort Bliss' commander, Maj. Gen. Howard Bromberg, declined repeated requests for an interview. Col. James Baunchalk, the base hospital's commander, acknowledged that the TBI program had encountered some delays, but said that it now had 12 clinicians -- four full-time and eight part-time -- who were delivering comprehensive care.

"I honestly believe that we've done a good job of meeting the needs for the community," Baunchalk said.

He promised in April that Building 805 would open by the end of May, saying they were just waiting until computer cabling was installed.

Apparently, they missed their deadline. As of early June, the clinic to screen soldiers for traumatic brain injury had not opened its doors to a single patient.

The Soldiers

Traumatic brain injuries are among the most common wounds sustained in Iraq and Afghanistan. Shock waves from bombs can pass through helmets and through the brain. Secondary trauma can occur when soldiers are thrown up against vehicles or walls, shaking the brain again.

Officially, the military says about 150,000 soldiers have suffered some form of brain injury since the wars began. But a 2008 Rand study suggests the toll is much higher, perhaps more than 400,000 troops. The most common type are so-called mild traumatic brain injuries. Most people recover quickly from such injuries, but studies have shown between 5 percent and 15 percent of patients may suffer long-term problems.

ProPublica and NPR interviewed more than a dozen soldiers at Fort Bliss who are among that so-called miserable minority. All were diagnosed by military doctors with at least one mild traumatic brain injury. All had persistent symptoms, ranging from headaches and vertigo to difficulties with memory and reasoning.

They described the bewildering ways in which their injuries had changed them. A sergeant who once commanded 60 men in battle got lost in a supermarket. A soldier who once plotted sniper attacks could no longer assemble a bird house. Most of them did not want their names used, for fear of harm to their military careers.

All felt the treatment they received was inadequate. At leading neurocognitive rehabilitation centers, some patients with mild traumatic brain injury often receive three to six hours a day of therapy for months from teams of highly trained specialists.

By contrast, many soldiers at Fort Bliss attended two to four hours of cognitive treatment per week. For some soldiers, weeks passed by with little or no treatment. The therapists who provided the soldiers with speech and occupational therapy for their brain injuries sometimes had only minimal training in cognitive rehabilitation, records show.

Staffing shortfalls also meant soldiers had long waits before beginning rehabilitative therapies. While clinical research is still developing, the consensus recommendation of a group of military and civilian experts convened by the Pentagon last year was to provide rehabilitation therapy as promptly as possible.

"The longer you go without therapy, the greater likelihood there is of falling into what I would call a mental disuse syndrome, where the brain is not being used at the same level," said Keith Cicerone, a leading rehabilitation researcher and the director of neuropsychology at the JFK Johnson Rehabilitation Institute in New Jersey. The brain "is in essence going to develop bad habits."

Sgt. Raymond Hisey, 32, a convoy driver in the 1st Armored Division, survived a roadside blast in Iraq in July 2009. He remained in the field, but endured constant headaches and balance problems. His short-term memory suffered and he struggled to think of words to express himself.

When he returned to Fort Bliss in October, he was diagnosed as having suffered a mild traumatic brain injury and was prescribed several courses of therapy. But a speech therapist cancelled several appointments, he said, and he clashed with the occupational therapist. Hisey was suddenly left without any treatment at all for his symptoms.

"You just get lost in the system," he said. "I could have pushed more, sure. But people kept saying it gets better over time. I thought I was just losing my damn mind, to be honest with you."

Fort Bliss is supposed to provide treatment to troops at smaller bases in the surrounding area. But one such soldier who developed headaches and balance problems after working on a mining detail in Afghanistan was told that no therapists could make regular trips to see him. Instead, the soldier, whose base was about an hour away from Ft. Bliss, was given antidepressants, which he did not take. He recently deployed for a second tour.

"As much as the military is making of TBI and the effects it's having on the soldiers and their families, I think for something as big as Fort Bliss, there'd be more people" to treat it, said the soldier, a specialist who did not want his name used for fear of damaging his career. "I was told there were no resources, no facilities."

Baunchalk, the hospital commander, said he had never heard such complaints from soldiers or their spouses. Soldiers were often reluctant to seek care, he said, because they perceived a stigma attached to traumatic brain injury.

"It's tough for them to step forward and say ... I need some help," he said. "I don't think we have that many soldiers who have fallen through the cracks."

Several soldiers told ProPublica and NPR, however, that they and their families had reached out to base commanders, sent e-mails to generals throughout the Pentagon, and even written to members of Congress, pleading for care.

When their efforts proved futile, they felt abandoned. Nobody paid attention, they said, to a soldier with an injury that nobody could see.

"No one listens to the soldier," said Sgt. William Fraas, an 18-year military veteran and Bronze Star recipient who struggled for nearly two years to get help for problems with his balance and vision. "They are there and they are crying for help."

The Neurologist

Fort Bliss soldiers struggling with the effects of brain injuries were often sent to the base's sole neurologist, Capt. Brett Theeler. Theeler, records show, sometimes blamed psychological disorders rather than blast wounds as the likely source of soldiers' cognitive problems.

A convoy commander in the 121st Brigade of the 1st Armored Division, Sgt. Victor Medina can see the moment he suffered his invisible injury. He was rumbling down a highway in southern Iraq June 2009 in a convoy of fuel, ammunition and supplies. Just behind him, in another armored troop carrier, one of Medina's soldiers was videotaping. Suddenly, the screen shakes. Black smoke jets into the air. Noise, swearing, confusion erupts.

A roadside bomb had exploded directly beside Medina. Metal slag ripped through his vehicle's heavy armor, destroying radio equipment and blowing open Medina's door.

Outwardly, Medina did not appear seriously injured. But in the weeks and months that followed, his mind began to fail him. He slurred his words, then started stuttering. An avid reader, he struggled to get through a single page. A punctilious soldier, he began showing up late for missions.

Medina was sent to Germany in August, where Army doctors diagnosed him as suffering from a traumatic brain injury. But when he returned to Fort Bliss for treatment, he and his wife, Roxana, found themselves fighting for care.

Medina had his first appointment with Theeler a month after his return to Ft. Bliss. Afterwards, Theeler wrote that Medina had "multiple cognitive symptoms including poor concentration, short-term memory loss, and difficulty multi-tasking." Theeler said those symptoms were "possibly" related to lingering effects from his concussion, but were "likely" caused by "chronic headaches" and "anxiety." He wrote that Medina's stuttering was probably caused by anxiety, too.

After a follow-up session with Medina in December, Theeler wrote:, "I am concerned that he may be slipping into a cycle of playing the sick role." He pointed to the fact that Medina was using crutches -- apparently unaware that a physical therapist had asked Medina to use the crutches because of back pain.

To Medina, 34, a tall, broad-chested man with an intense stare, Theeler's words were insulting. Once praised by superiors for his leadership abilities, Medina worked relentlessly to overcome the staccato stutter that had made him difficult to understand. He was fighting to get better, fighting to remain in the Army. He said he felt he was being labeled a liar.

"You have all these values that you live for and fight for. And you go to the medical side and you don't see those values," Medina said. "I can understand being injured by insurgents. But I can't understand being injured by my own people."

Other soldiers had similar experiences with Theeler.

By the time Spec. Ron Kapture got to Fort Bliss in July 2009, he had suffered six concussions in which he was knocked unconscious from blasts, according to medical records and his own recollections.

He was suffering headaches on a daily basis. He noticed that he could no longer do simple mental tasks. Before joining the Army, Kapture had gone to vocational school to learn cabinet making. After returning from Iraq, he struggled to put together a bird house with his son.

"It took us about a month," said Kapture, 28. "I could build a whole living room full of furniture in a day seven years ago. It took me a month to build a bird house. That is frustrating stuff."

Five months after his return, Kapture finally got an appointment to see Theeler after making repeated requests. Theeler noted that Kapture had a history of "mild concussions," but blamed his cognitive problems on "chronic headaches, sleep disorder and underlying mood anxiety disorders and depressions," records show.

Kapture received counseling and medication for post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, but his problems with memory and concentration persisted. He had planned to make the Army his career, but became so embittered at the handling of his care that he is applying for a medical dismissal.

"If that's the best help they ... can give us, then God help us all," Kapture said. "If that's the best they have to offer, I feel sorry for the guys coming home."

In an interview at the base, Theeler declined to comment on individual cases, even in cases where soldiers had signed a waiver of their privacy rights. He said, more generally, that he understood why soldiers like Medina and Kapture were frustrated. Mild traumatic brain injury can be difficult to pinpoint as a cause for soldiers' problems since there are no readily available biological markers to indicate that a concussion has occurred, he said.

Theeler said he concentrated on treating soldiers' symptoms regardless of the cause.

Soldiers "say, 'Sir, what's wrong with me?'" Theeler said. "We're honest. I say, 'I don't know what's wrong.' This is an area that we're working very hard at to get our hands around. I don't know the answers."

The PTSD Clinic

Some doctors and soldiers at Fort Bliss said medical commanders have placed a higher priority on treating post-traumatic stress disorder, a psychological condition, than on mild traumatic brain injury.

As evidence, they point to the fate of two clinics. While Building 805 remains unopened, the base has poured money and effort into an experimental PTSD clinic that has attracted widespread attention within the military, including a visit from Defense Secretary Robert Gates.

Known as the Restoration and Resilience Center, the clinic offers intensive, six-month-long treatment for chronic PTSD sufferers, including controversial techniques such as reiki, in which practitioners hover their hands over patients' bodies to improve the flow of "life energy," according to a pamphlet distributed at the center.

Brain injuries and PTSD sometimes share common symptoms and co-exist in soldiers, brought on by the same terrifying events. Neuropsychologists said that treatments for the conditions can differ, however. A typical PTSD program, for instance, doesn't provide cognitive rehabilitation therapy. Someone with nightmares associated with PTSD might be prescribed sleep medication, which could leave a brain-injured patient overly sedated without having a therapeutic effect.

One doctor at Ft. Bliss said that base commanders' focus on the PTSD clinic resulted in soldiers not getting adequate treatment for brain injuries.

"The way our philosophy is in this hospital ... we took away their belief that they truly have something," said the doctor, who did not want his name used for fear of retaliation from commanders. "I don't think we gave them the opportunity to heal and that's what I find really disgusting."

Some soldiers said they spent months receiving PTSD treatment while their cognitive problems went unaddressed.

Sgt. William Fraas, 38, the sergeant who was awarded the Bronze Star With Valor, served three tours in Iraq, helping to train the Iraqi soldiers as part of the 101st Airborne Division, 320th Field Artillery. He was given his medal after after rescuing an Army major and six Iraqi soldiers pinned down by gunfire. Driving in his Humvee, he used to keep track of the roadside bombs with a black grease pencil on the windshield. After 10, he stopped counting.

When he was sent home to Fort Bliss in 2008, he was diagnosed with PTSD and entered the experimental clinic. He spent eight months there before being cleared to return to active duty.

But Fraas realized he was still having problems. He was constantly dizzy. He had debilitating headaches. He would call his wife when driving, so she could keep him oriented and awake.

He began having blackouts. Once, he awoke to find his 12-year-old son struggling to lift him after he collapsed in front of his home computer.

"They have these meetings for PTSD. But nowhere did they tell you anything about TBIs. We had no idea what was going on," he said. "It feels like my head is loose. Like my brain is loose. Like it's rattling inside my head."

Finally, last summer, Fort Bliss doctors sent him to see a physical therapist at the base to improve his balance. But the appointments were irregular. And with his inability to drive, he had trouble getting around the sprawling base. A case manager who was supposed to coordinate his care asked one of Fraas' friends if he was faking it. A second case manager never even contacted him.

After putting nearly 20 years into the military, he was stunned.

"I could not get help. I called and called and called. I was hurting," he said. "It was just terrible. I'm a senior non-commissioned officer and I couldn't get help. I couldn't get help anywhere."

Mentis

Some Fort Bliss soldiers have discovered that if they protest long and loud enough about their care, base commanders occasionally will pay to send them for help -- outside the military.

On a hot afternoon earlier this spring, Sgt. Brandon Sanford was digging a small trench in the black soil of a rose garden at Mentis, a private neurological rehabilitation facility perched on the mountains just outside of El Paso.

He was installing an irrigation drip line as part of a therapy program designed to help him follow instructions. He set in one line, then covered up the trench. Then, looking down, he suddenly realized that he had failed to install the second drip line he was holding in his hand.

It was a typical problem for a brain-injury patient. Concentration deficits can make even simple tasks complex and confusing. Sanford immediately began pulling up the first line, digging again.

"That can be frustrating," the therapist overseeing the exercise said sympathetically.

"Never," said Sanford cheerfully. "I ate my Wheaties this morning."

Almost two years ago to the day, Sanford, a dog handler working with the 4th Infantry Division, was inside his Stryker troop carrier near Taji in central Iraq when a bomb exploded. The blast sent Sanford and his dog, Rexo, hurtling against the walls. Both were awarded the Purple Heart for shrapnel wounds they received in the explosion. Although dazed, Sanford shrugged off the headaches and dizziness he experienced and continued working.

When Sanford returned to Fort Bliss in January 2009, he began having seizures, along with continued headaches and balance problems. He saw the base neurologist, Theeler, who diagnosed him as having "shaking syndrome," medical records show.

He entered the PTSD clinic, received counseling and was released, but was still so mentally foggy he couldn't understand his 10-year-old son's math homework. His wife would open the cupboard where they kept cleaning supplies and find that her husband had put the milk carton next to the bleach. Sanford's wife and mother badgered military commanders unrelentingly until, nearly a year after his return from Iraq, they finally sent him to Mentis.

There, Sanford is an in-patient: he spends eight hours a day, five days a week, on rehabilitation exercises. He goes on weekly outings to help him navigate the noise and confusion of public spaces, such as shopping malls. And he practices real-world tasks, like following cooking recipes -- or laying out plans for a garden.

Today, Sanford said that he is able to finish making meals more quickly. He can now perform two tasks at once, instead of only one. He is getting better at managing his own medications and his balance has improved.

"You can only do so much sitting inside a hospital. It was like pulling teeth from a tiger to try to get in here. Once I got in here, it was like a whole new ray of light."

Eric Spier, Mentis' medical director, said he has asked the military to send him more patients. But base commanders have sent only a few dozen in almost three years.

"I've made sure to tell everyone I can tell that I'm ready to help, but that's all I can do," Spier said. The base has not sent "very many. It's surprisingly few."

Fraas and Medina now attend sessions at Mentis. They praised the facility, but expressed disappointment that they had had to go outside the Army to receive help.

Medina started in February. The staff at Mentis say his reading and concentration abilities are improving. His growing optimism is apparent in the blog he has started to chronicle his recovery.

"I might be slower right now, but I think it's all going to get better and I want to go back to what I love doing, which is soldiering," Medina said. "It's what I love to do."

Soldier Brain Injuries to Get Senate Scrutiny After ProPublica, NPR Report

"The recent NPR and ProPublica reports on the military's diagnosis, treatment, and tracking of traumatic brain injuries are concerning," Sen. Carl Levin, D-Mich., said in a statement.

NPR and ProPublica reported this week that the military was failing to diagnose soldiers with so-called mild traumatic brain injuries. Such injuries, also called concussions, are typically difficult to detect but can cause lasting mental and physical difficulties.

Unpublished military studies and interviews with medical officials suggest there could be tens of thousands of soldiers suffering undiagnosed traumatic brain injuries, which have been called one of the signature wounds in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. When soldiers were diagnosed, many received little or no treatment, even at large bases such as Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas.

Official military statistics say 115,000 troops have suffered a mild traumatic brain injury since the wars began. But in interviews, top Army medical officials acknowledged that those figures understate the true number.

Civilian studies suggest up to 15 percent of people with mild traumatic brain injuries experience lingering problems with memory, concentration, sleep and balance problems.

"While the Department of Defense and the military services have made progress toward increasing knowledge about and awareness of the causes, diagnosis, and treatment of traumatic brain injuries, there is still a good deal to learn, both in the military and civilian medical environments," Levin said in his statement.

Levin2019s spokeswoman said the hearing will take place later this month, though the date has not been finalized. It will look at the complex web of illnesses that have afflicted troops returning from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the role those disorders play in soldier suicides. The issue has been a growing concern in the military.

Soldiers with traumatic brain injury often also suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, a debilitating psychological wound. Those who survive roadside blasts can suffer both a brain injury and PTSD, which can be triggered by the terror of the event.

"Traumatic brain injury, post traumatic stress, and suicide are all related issues, at times making diagnosis difficult," Levin said in his statement.

Army officials said they have been working to improve their systems to diagnose soldiers. They said soldiers with brain injuries have received appropriate treatment.

In an interview earlier this week, Gen. Peter Chiarelli, the Army's vice chief of staff, said the military took traumatic brain injuries "extremely seriously."

Chiarelli, who has worked to raise awareness about the severity of so-called invisible wounds such as mild traumatic brain injury and PTSD, said medical officials must diagnose and treat a complicated mix of illnesses.

"It's time we realize that TBI and PTSD are real injuries," Chiarelli told "Talk of the Nation" host Neal Conan. "We've got to ensure our soldiers get the care that they need."

Congress Demands Answers on Brain Injury Care at Texas Base

Rep. Harry Teague, D-N.M., Rep. Silvestre Reyes, D-Texas, and Rep. Ciro Rodriguez, D-Texas, sent a letter to Fort Bliss' William Beaumont Army Medical Center on Tuesday expressing concern over our report that soldiers encountered debilitating delays and frustrating bureaucracy when seeking help at the base, America's third largest by number of soldiers.

A spokeswoman for Teague said today that the congressman was also considering calling for the U.S. Government Accountability Office to review the military's handling of traumatic brain injuries and may pay a visit to Fort Bliss to personally inspect the facilities.

"We are deeply concerned that our government could be failing those to whom we owe the most," the three men wrote in their letter. "These reports must be investigated and receive the full attention of the United States Congress and government."

In our investigation, we found that soldiers at Fort Bliss struggled to receive diagnosis and treatment for so-called mild traumatic brain injury. Such head traumas, also called concussions, often leave no visible signs of damage, but can result in long-term mental and physical problems.

Official military figures show that about 115,000 troops have suffered mild traumatic brain injuries since 2002. But we found that many troops have injuries that go undiagnosed or that are never documented in their medical records. Top Pentagon officials acknowledged in interviews that the true toll is likely far higher. Unpublished military studies reviewed by ProPublica and NPR suggest tens of thousands of mild traumatic brain injuries have gone uncounted.

Most soldiers with concussions recover quickly, but civilian studies indicate that 5 percent to 15 percent of those who suffer such injuries have lingering cognitive problems.

The Senate Armed Services Committee announced Wednesday that it will hold a hearing on June 22 to look into suicide, traumatic brain injury and other so-called invisible wounds.

Our investigation found that Fort Bliss had erected billions of dollars of new housing and accommodations for additional troops to deploy to war zones, but had failed to open the doors of Building 805, a traumatic brain injury clinic completed nearly a year ago. Although the Pentagon designated the base as a site for enhanced treatment for brain-injured soldiers in 2007, the base did not hire a full-time director for the program until October 2009.

Soldiers at Fort Bliss told us they waited weeks or months just to get appointments to see doctors and often received far fewer hours of therapy than patients at well-regarded civilian clinics. Some were prescribed therapy for psychological problems that did little to relieve their troubles with memory, balance and reasoning.

The three congressmen, who are part of the bipartisan Congressional Invisible Wounds Caucus, have asked the medical commander at Fort Bliss, Col. James Baunchalk, to answer several questions about the base hospital's treatment program.

They asked to know how many patients with traumatic brain injury, or TBI, were being treated at Fort Bliss, how long soldiers had to wait for appointments, and whether the hospital had systems in place to address soldiers' complaints.

"It's pretty important that (Fort Bliss) be at the front of addressing TBI and PTSD," Teague said in an interview. PTSD, or post-traumatic stress disorder, is a psychological wound that often accompanies TBI.

Fort Bliss officials have declined to answer such questions from ProPublica and NPR. Baunchalk also denied ever having received complaints regarding brain injury care, despite e-mails and letters written to his assistants and superiors by soldiers and family members.

Fort Bliss officials have defended their treatment of soldiers. In a response this evening, a base spokesman said they would respond to all questions posed by the congressmen by June 21.

"Our commitment is to provide quality health care, in a timely manner, to those who serve in our military," the statement said.

Congress Questions Military Leaders on Suicides, Traumatic Brain Injury

Responding to what he called "disconcerting" reports by NPR and ProPublica, Sen. Carl Levin, D-Mich., said at a hearing before the Senate Armed Services Committee that the military needed to better address the wide range of medical and behavioral problems affecting troops.

Earlier this month, we reported that the military was failing to diagnose and adequately treat troops with brain injuries. Since 2002, official military figures show more than 115,000 soldiers have suffered mild traumatic brain injuries, also called concussions, which leave no visible scars but can cause lasting problems with memory, concentration and other cognitive functions.

But the unpublished studies that we obtained and the experts that we talked to said that military screens were missing tens of thousands of additional cases. We also talked to soldiers at one of the military's largest bases, who complained of trouble getting treatment.

"I am greatly concerned about the increasing number of troops returning from combat with post-traumatic stress and traumatic brain injuries, and the number of those troops who may have experienced concussive injuries that were never diagnosed," Levin, chairman of the committee, said as he opened today's hearing.

Gen. Peter Chiarelli, the Army's vice chief of staff, said the Army had made strides in identifying soldiers at risk of committing suicide, setting up new treatment centers and deploying a new system of "telemental health services," allowing soldiers to talk with counselors by computer video chat programs.

Chiarelli's remarks were echoed by other senior military commanders at the hearing from the Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps.

"Our success notwithstanding, we still have much more to do," said Chiarelli, who has emerged as the Army's point man on mental health issues. "We face an Army-wide problem that will be only be solved by the coordinated efforts of our commanders, leaders, soldiers and program managers and health providers. This is a holistic problem with holistic solutions and that is how we're approaching it."

Chiarelli acknowledged that the Army continues to have problems with properly diagnosing soldiers with mild traumatic brain injuries, saying that it was an emerging area of medicine. And he acknowledged that soldiers at bases throughout the Army have sometimes had trouble receiving treatment for mild traumatic brain injuries and post-traumatic stress.

Chiarelli took issue with our reporting, however. He said the NPR and ProPublica reports were wrong to blame military doctors for failing to diagnose the problem, or to accuse senior military officials of not taking the issue seriously. He also said that NPR and ProPublica had tried to draw a distinction between traumatic brain injury, or TBI, and post-traumatic stress, or PTS, two conditions which frequently occur together.

"I think the great disservice that NPR did to everyone was to try to isolate TBI from PTS. And that is just not possible," Chiarelli said. "The co-morbidity of these two is what's giving us the difficulty today. And I also think that they did a disservice when they indicated that PTS is a psychological problem. It's not just at a psychological problem. It is a physical injury that occurs."

Chiarelli did not cite any factual errors in the stories and we stand by our reporting. But we also think he is mischaracterizing our reporting, which was based on dozens of interviews with senior military researchers, commanders and soldiers, and thousands of pages of unpublished studies, e-mails and medical records.

First, we did address the overlap of TBI and PTSD in our stories: "To be sure, brain injuries and PTSD sometimes share common symptoms and co-exist in soldiers, brought on by the same terrifying events," we wrote.

We also did not downplay the seriousness of PTSD -- a wound which NPR has reported on extensively in past stories.

We found several instances in which military doctors expressed skepticism about mild traumatic brain injury and its effects. Dr. Charles Hoge, one of the Army's senior health advisers, referred to the "illusory demands" of mild traumatic brain injury in an opinion piece in the New England Journal of Medicine last year. In an April 2010 e-mail that we obtained, he wrote: "What's the harm in missing the diagnosis of mild TBI?" In an interview, Hoge told us that he was concerned with treating soldiers' symptoms, no matter the cause.

We also turned up extensive evidence that military doctors weren't diagnosing mild traumatic brain injuries, both on the battlefield and when troops came home. Battlefield medics, overwhelmed by life-threatening wounds, can miss the signs of concussions. Screening tools now in place often fail to catch soldiers who have suffered concussions. Soldiers often try to hide their symptoms to return to battle with their comrades.

One of the Army's senior neuropsychologists told us of examining five soldiers who had survived a rocket attack in Iraq last year. Medical staff had treated their visible wounds, but failed to diagnose them as suffering from mild traumatic brain injury -- even though they were suffering "classic" symptoms, according to Lt. Col. Mike Russell.

It is important to diagnose mild traumatic brain injury and quickly provide treatment for any lingering effects, according to the Pentagon's own experts. While the majority of soldiers recover quickly from concussions, some report lasting mental and physical problems. Studies show that such soldiers can be helped by providing cognitive rehabilitative therapy, an intensive program to retrain the brain to perform mental tasks.

Sen. Mark Udall, D-Colo., asked Chiarelli several questions about the military's efforts to improve how it diagnoses traumatic brain injury. Afterwards, he said that he appreciated Chiarelli's efforts, but planned to continue pressing Army officials on the issue.

Udall "remains concerned about the impact of TBI and PTSD on our service members," Tara Trujillo, a Udall spokeswoman. "As discussed at the hearing, there is much still to learn, different approaches to take and ways to continue to improve."

After the hearing, Levin said he was convinced that the services were trying to properly diagnose mild traumatic brain injury.

"I remain concerned about the diagnosis of traumatic brain injuries, and especially of mild traumatic brain injuries, but it is not for lack of the services trying to do the best they can with existing science, tools, and methods," Levin said in a statement. "There is still much to be learned in both the military and civilian medical environments about the diagnosis, treatment, and care of traumatic brain injury, and its relationship to other combat-related injuries such as post traumatic stress. I believe each of the services is taking the issues of detection, tracking, and follow-up care very seriously, but there is still work to be done."

Leader of Military’s Program to Treat Brain Injuries Steps Down Abruptly

WASHINGTON, D.C.--The leader of the Pentagon's premier program for treatment and research into brain injury and post traumatic stress disorders has unexpectedly stepped down from her post, according to senior medical and congressional officials.

Brig. Gen. Loree Sutton told staff members at the Defense Centers of Excellence, or DCOE, on Monday that she was giving up her position as director. Sutton, who launched the center in November 2007, had been expected to retire next year, officials with knowledge of the situation said. The center has not publicly announced her leaving.

Sutton's departure follows criticism in Congress over the performance of the center and in recent reports by NPR and ProPublica that the military is failing to diagnose and treat soldiers suffering from so-called mild traumatic brain injuries, also called concussions.

It comes just as the Pentagon prepares to open a new, multimillion-dollar showcase treatment facility outside Washington, D.C., for troops with brain injuries and post traumatic stress disorder, often referred to as the signature wounds of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Late Wednesday, in a sign of disarray within the program, Sutton cancelled a scheduled appearance at the opening of the National Intrepid Center of Excellence, a gleaming new facility of waving glass and futuristic virtual reality treatment rooms in Bethesda.

"The war in Iraq and Afghanistan could end tomorrow; our mission to restore health, hope and humanity will endure for decades," Sutton wrote in her farewell message. "We simply must uphold our commitment to all who have borne the burdens of war on our behalf."

Sutton did not respond to requests for comment. Her replacement, U.S. Army Col. Bob Saum, also declined to comment.

Cathy Haight, the acting spokeswoman for DCOE, said Sutton's departure, though apparently well ahead of schedule, was part of a routine command rotation. Haight said Sutton decided to leave after turning down the Army's offer to take a new position overseeing the military medical system in Europe.

"If a general officer declines (a new position)...they are in a transition to retire," Haight said.

In recent months, legislators have questioned Sutton's ability to carry out the mission of the centers, which is to catalyze research and treatment across the military for soldiers returning with brain injuries and psychological wounds.

Congress directed the military in 2008 to create the brain injury center and other facilities for wounded soldiers. At an April hearing of a House Armed Services subcommittee, Rep. Susan Davis, D-Calif., said that the center had failed to carry out its role.

"The Defense Center of Excellence, while having achieved some notable small scale successes, has not inspired great confidence or enthusiasm thus far. The great hope that it would serve as an information clearinghouse has not yet materialized," Davis said.

"The center has also made some serious management missteps that call into question its ability to properly administer such a large and important function," Davis continued.

Scrutiny of Sutton rose another notch earlier this month, when NPR and ProPublica reported on the military's problems in handling soldiers with mild traumatic brain injuries. Such injuries leave no visible scars, but can cause lasting mental and physical difficulties.

Military statistics show that about 115,000 troops have suffered such injuries since 2002, but in interviews, Army experts acknowledged the true toll may be far higher. Unpublished research we reviewed suggests that tens of thousands of soldiers may have gone undiagnosed. Our reporting also showed that even when soldiers were diagnosed, at one of America's largest Army bases, they have had to fight to receive appropriate treatment.

Still, some veterans' advocates were shocked and saddened that Sutton was leaving. They said she had been a forceful, visible advocate for wounded troops and their families who had never received the full support of the military's medical establishment.

Critics of the military's health system have noted a power vaccum at the top of the military medical structure. Four people in just over three years have rotated through the Pentagon's top health policy position, the assistant secretary of defense for health affairs.

"She was always there for the troops," said one veterans' advocate, who did not want to be named for fear of criticizing the military. "She's become the scapegoat."

In an April interview with NPR and ProPublica, Sutton shrugged off the criticism. "Leading change," she said, "is a journey not for the faint of heart."

"We are very proud of the team that we have built, the concept in terms of the center of centers, the network of networks," she said. "Are we anywhere close to where we want and need to be? No. Of course not."

Pentagon Shifts Its Story About Departure of Leader of Brain Injury Center

Earlier this month, we reported that the military was routinely failing to diagnose such injuries, which are the most common head wounds sustained by soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan. We also found that soldiers had trouble getting adequate treatment at one of America's largest military bases, Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas.

Since then, Congress and the military have taken a number of steps to redress the issues we raised. The Senate Armed Services, for instance, grilled military leaders on the topic at hearing. Rep. Harry Teague, D-N.M., wrote a letter demanding answers on the care at Fort Bliss.

We also reported last week that the leader of the Pentagon's premier research center into brain injury had unexpectedly stepped down just days before the June 24 dedication of a new, cutting-edge medical center for head traumas, post-traumatic stress disorder and other so-called invisible wounds of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Then things got strange. Our story quoted a spokeswoman for Brig. Gen. Loree Sutton who said Sutton was stepping down from the Defense Centers of Excellence because she had turned down a post in the military's European medical command, a decision that meant she would retire. The spokeswoman, Cathy Haight, described it as part of a normal process of command rotation.

Two days later, we got a message from Sutton's boss, Charles Rice, the assistant secretary of defense for health affairs. A Pentagon spokeswoman, Eileen Lainez, said that Haight "misspoke." Sutton stepped down after Rice decided "that a change in leadership was necessary to continue moving the organization forward," Lainez said.

This struck us as odd. Was Rice going out of his way to tell us that he had fired Sutton? If so, why? And why did he decide to ask Sutton to step down only days before the dedication of the National Intrepid Center of Excellence?

Lainez had no further comment. "I'm just providing clarification on the reassignment," she said.

Then it got weirder still. As part of the original story, which ran the day before the dedication, we reported that Sutton had canceled her appearance at the ceremony, citing this press release from the center: "BG Loree K. Sutton will no longer be in attendance."

Afterward, another spokeswoman for the general contacted us to say that Sutton had never canceled. She said the press release issued by the center was wrong. Sutton had attended the ceremony and several related events.

"Clearly, there was some confusion and I understand how this mistake could occur in the final hours of preparation of the event," Judith Evans wrote. Sutton, she said, "was seated in a VIP section ... and acknowledged by speakers during remarks at the ceremony."

Evans declined to answer any follow-up questions on Sutton, who also did not respond to requests for clarification. The Defense Centers of Excellence still has not announced her departure publicly. Sutton now works in the office of Army Surgeon General Eric Schoomaker.

The new center, which is in Bethesda, Md., apologized for the error: "We understood the information about Gen. Sutton's attendance at the NICoE dedication ceremony to be correct at the time and regret any miscommunication," said Jody Fisher, a spokesman for Rubenstein Communications, the firm that handled PR for the event. "We were very pleased that she was able to attend the event."

Sutton had both fans and enemies, as we reported. Congress found fault with her management skills, but some veterans' advocates praised her tireless devotion to soldiers and their families.

Critics of the military's health system have noted a power vacuum at the top of the military medical structure. Four people in just over three years have rotated through the Pentagon's top health position, the assistant secretary of defense for health affairs.

One figure reportedly upset by the way the new $65 million brain-injury center debuted was Arnold Fisher, a New York real estate magnate and philanthropist who led the fundraising to build it.

Fisher, according to The Washington Post, said it was "unacceptable" to ignore the needs of wounded veterans. He criticized the White House for not sending any representatives to the ceremony.

"These are the very people who decide your fate," Fisher told the Post. "We are all here, but where are they?"

Fort Bliss Says It Will Examine Its Handling of Brain Injuries

Medical commanders at one of America's largest military bases have ordered a review into the care provided to soldiers suffering from traumatic brain injury, in response to an investigation by NPR and ProPublica.

Col. James Baunchalk, the commander of William Beaumont Army Medical Center at Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas, told members of Congress that he was concerned by our report, which found that soldiers there struggled to receive adequate care for mild traumatic brain injuries.

The hospital is "committed to delivering the very highest quality care and support to our soldiers and their families, including those who may be affected by traumatic brain injuries," Baunchalk wrote in a June 21 letter to Rep. Harry Teague, D-N.M., a copy of which was obtained by NPR and ProPublica.

The Pentagon's official figures show that more than 115,000 troops have suffered mild traumatic brain injuries, also called concussions, since the wars began in Iraq and Afghanistan. But our story said those figures likely understate the true toll, with some studies suggesting that the injuries go undiagnosed in tens of thousands of troops. While most recover quickly, some grapple with lasting mental and physical problems from exposure to explosions.

Our story focused on several soldiers at Fort Bliss, the third-largest American military base by troop population. The soldiers told us they endured long waits to see specialists and met with frustrating skepticism from doctors over the severity of their conditions. All had ongoing problems with memory, concentration and other cognitive functions.

We also wrote about Building 805, a small clinic at the base that was supposed to screen soldiers with traumatic brain injuries. Although the base has recently added billions of dollars of barracks and other facilities to accommodate newly arriving troops, Building 805 has remained shuttered for almost a year, for want of computer wiring, commanders told us.

Teague, who visited the base on Sunday and met with soldiers mentioned in our story, said he would continue to press the hospital to make sure that adequate care was being delivered.

"I would like to further examine how the overall quality of TBI care at Fort Bliss serves our soldiers compared to what they may have access to in civilian medicine," Teague wrote in a June 25 letter to Baunchalk. "I would like to ensure that the system of TBI care, in general, adequately addresses the needs of our service members and is adequately resourced."

Base officials did not immediately respond to requests for comment on their letter to Teague. The letter listed a series of programs in place to treat soldiers and catch problems in care, but some of the information appeared to contradict material that base officials provided to us.

Fort Bliss told Teague it had 10 medical staff members "assigned full time" to the traumatic brain injury program. But in a letter responding to our questions in April, officials listed only four employees providing such care full-time. They listed seven other clinicians who worked part-time with brain-injured patients.

Fort Bliss also told Teague that Building 805 was "completed at the end of January 2010." But in interviews with us and in their written response to our questions, base officials told us that Building 805 "was completed in July 2009," though utilities were not installed until February 2010.

Fort Bliss officials also told us during our visit there in April that Building 805 would be open at the end of May. In their letter to Teague, they said that they had not even issued a contract to install the computer wiring until June 17 2014 nine days after our stories ran.

Sgt. Victor Medina and his wife, Roxana Delgado, who were featured in our stories, said they were pleased that Teague and others have paid attention to soldiers' concerns about treatment for brain injuries. Medina had to fight to get referred off base to a private medical facility specializing in cognitive rehabilitation.

But, they said, more work remains to be done.

"We're seeing a lot of progress in terms of attention and interest," Delgado said. "But we want to see more. We want to see real reform."

Update: Fort Bliss got back to us on Thursday to respond to our questions with this letter. They reiterated that the Fort Bliss program has 10 "full time" clinicians devoted to traumatic brain injury, though one slot is vacant.

They also said that Building 805, a clinic for screening soldiers with traumatic brain injury, was completed for occupancy earlier this week. The process to move in clinical staff has begun, according to the written responses.

Finally, Fort Bliss acknowledged for the first time that the base has not yet received full validation under Defense Department guidelines for its traumatic brain injury treatment program. Fort Bliss is designated a "Level 2" facility, meaning it is supposed to have one of the top 10 treatment programs in the U.S. to address mild and moderate brain damage. Fort Bliss officials said Thursday that the base passed an initial round of examination, but does not expect to receive full validation of its program until Fall 2010.

Rep. Teague Pledges Deeper Inquiry Into Treatment for Brain-Injured Soldiers

In a letter to medical commanders at Fort Bliss, the third-largest Army base in the country, Teague, D-N.M., wrote that he had turned up troubling evidence of systemic problems across the military in the treatment of soldiers suffering lingering cognitive difficulties as a result of roadside blasts.