The Days After

In 2004, law enforcement agencies in Lafayette Parish made nearly 700 arrests on domestic violence-related charges, an average of almost two daily.

While that number may be surprising to many, for Lafayette police Detective Michael Brown, it's not.

"I don't doubt the numbers," he said. "That's only what has been reported. And how many of those are repeats? The number's probably more than that."

To develop a complete picture of a year in domestic violence in Lafayette, The Daily Advertiser combed through police arrest records for every day in 2004.

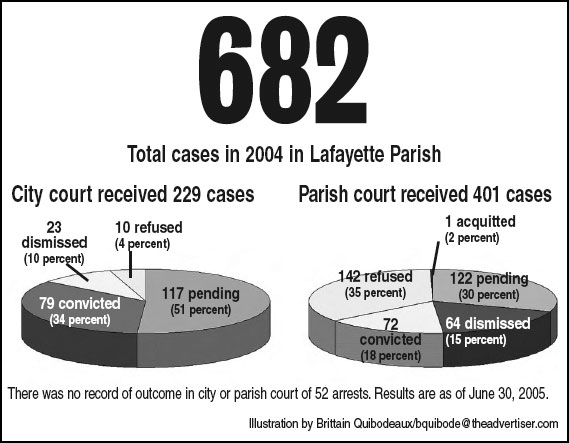

From January to December, there were 682 arrests that police identified as domestic crimes. They ranged from physical abuse to damaging property to violating protective orders. Some of those listed had been arrested two or even three times in a single year.

Yet by mid-2005, fewer than half of all the arrests on domestic violence charges have resulted in convictions, according to a review of police and court records by The Advertiser.

Using courthouse computer records, data obtained from parish prosecutors and information obtained after a public records request to city prosecutors, The Advertiser was able to determine how many cases from 2004 had actually made it through the court system.

Prosecutors cite a variety of reasons why an arrest doesn't always result in a conviction. Many times, victims of domestic violence, out of fear of retaliation from their abusers, fail to show up in court. And without the victim to testify, there is little prosecutors can do, they say. Sometimes, offenders are persuaded to enter counseling in exchange for charges being dismissed before trial. Sometimes, police reports don't contain enough evidence to support the charges.

The Advertiser's study also shows:

- In city court, one in every two cases from 2004 were still pending as of June 30.

- Parish prosecutors declined charges in 142 cases, or one out of every three.

- Of the cases that went to court, 22 percent were dismissed by city court judges and 47 percent were dismissed by parish court judges.

- There were 52 arrests made in 2004 in which there was no court record as of June 30.

City court prosecutions take time

According to The Advertiser's study, 22 percent of all the arrests for domestic violence last year were dropped before they ever made it before a judge.

As of June 30, 229 cases from 2004 were assigned to city prosecutors. Of those, 79, or 35 percent, had resulted in convictions. Of the cases assigned to parish prosecutors, 72 of 401, or 18 percent, had resulted in convictions.

In Lafayette, city court handles only misdemeanor cases. That includes cases of simple battery, where any type of unwanted touching occurred but no weapon was used, and simple assault, where a threat of physical harm was made.

The more serious cases of aggravated assault or aggravated battery, where an alleged offender has threatened with a weapon or has used a weapon against a victim, go to parish court. Parish court also handles all of the cases where arrests are made outside the city limits and all violations of protective orders.

As of June 30, Lafayette's two city prosecutors had garnered convictions in 35 percent of the cases they were assigned in 2004.

Lafayette City Prosecutor Gary Haynes said that's because his office accepts most domestic violence cases.

"Once we pick it up, we're going to go forward with it if we have the evidence to," he said.

City prosecutors refused to pursue charges in only 10 of the cases they received in 2004.

"We take the position that even in that swearing contest where there's a 50/50 chance, we're going to take the chance of winning the case based on the credibility of the victim," he said.

But those prosecutions took time. More than half of the cases from 2004 were still awaiting a conclusion in city court. In parish court, 30 percent of the cases from 2004 were still pending on June 30.

Parish court has more refusals

In the Lafayette Parish Court, two assistant district attorneys share the misdemeanor caseload, which includes both domestic abuse battery and simple battery cases. Any felony case, which includes aggravated battery, is given to any one of 11 assistant district attorneys. In 2004, parish prosecutors refused charges in 142 domestic violence cases, or one out of three.

According to Janet Perrodin, who is an assistant district attorney specializing in domestic violence cases, the reason cases are refused often has to do with insufficient evidence.

When police or sheriff's deputies make dual arrests - arresting both the aggressor and the victim in a dispute - it can be difficult for prosecutors to know whom to prosecute.

According to Perrodin, the district attorney's office has a no-drop policy, which means prosecutors won't drop charges against an offender just because a victim asks for it.

However, since one of the main components of a successful case is the victim's testimony, cases in which a victim does not cooperate often are dismissed.

Out of the 401 cases sent to parish prosecutors in 2004, 64 were dismissed.

"I can't see any other reason that a case is dismissed other than we don't have the victim in court to proceed and we need the victim," she said, when told of the number of dismissals.

"If you can find one case where a victim is upset because we dismissed a case, I would like to know that, because there is not going to be any," she said.

Prosecuting without a victim

Perrodin reviewed her files for domestic violence cases in 2004 and shared her notes on why cases she handled were dismissed. Many times, it was because victims did not show up in court or exercised their right not to testify against a spouse.

"We would love to be able to prosecute a case without a victim. If we had eyewitnesses, if we had other kinds of evidence. It's all about proving a case beyond reasonable doubt," Perrodin said.

Brown said he is aware of that problem and has learned to treat each case as if there were no victim.

"I already have that in my mind that the victim is not going to testify against her husband or her boyfriend," he said. "In my reports, I will put enough information in there to show the behavior of the aggressor and of the victim from past instances."

But not all police officers do that, so many cases rest on the victim's word, prosecutors say.

Lafayette City Court Judge Douglas Saloom said at times he's been forced to take a hardline approach when dealing with reluctant victims.

"We've had to actually issue warrants for the arrest of the victim just to force them to come to court," Saloom said.

The option for counseling

In many cases, by the time the case goes before a court, six months have passed and the victim and abuser have long since been back together, Perrodin said.

"The general turnaround time is six months, and six months is a long time in a domestic relationship. A week is a long time," she said. "It's a major frustration."

Since prosecutors are not always guaranteed a conviction, the best thing they can do is to get the defendant some education or counseling and treatment to change the behavior, Perrodin said.

She said they often will drop a weak case or a case in which the offender lacks a significant criminal record in exchange for counseling. Options include the 26-week course for batterers called the Family Violence Intervention Program or an anger management class.

"That's the most important thing: Get the FVIP counseling. I'll end up dismissing the case, but I'm not dismissing the case because (the victim is) asking," she said.

Choosing among counselors

However, even after convictions, not all abusers are sentenced to counseling. In at least 30 out of the 72 convictions in parish court, there was no record of counseling being mandated as part of the sentence.

Out of 79 convictions in city court, city prosecutors and judges allowed at least 23 abusers to be sentenced without the benefit of counseling.

City prosecutor Haynes said offering defendants FVIP, which costs them $20 per session, is not always considered a reduced sentence when he's trying to make a plea deal.

"Six months of FVIP class, for some people, is almost like jail," he said.

Some prefer to take the six-hour anger management class instead of FVIP.

It is an issue that Cathy Broussard, executive director of FVIP, said she faces time and time again.

In her opinion, sending batterers to anger management is not getting them the counseling they need.

"Anger management is for barroom brawls and fights on the streets," she said, but domestic violence is about something else entirely. "It is a system of beliefs geared toward controlling another."

- Previous Section

The Days After - Next Section

Lafayette Among Top 5 Parishes for Protective Orders