Germany and Post-War Trauma

On Tuesday January 18th, Germans and non-Germans were brought together by the Dart Centre at the Frontline Club in London to discuss how Germans have dealt psychologically with their country’s complex history.

The Second World War and the gruesome outcome of Adolf Hitler’s regime traumatised nations, communities and individuals. Since the war, this has been openly discussed on an international level, but in Germany itself it has been much more difficult.

The country does its part to educate people about what happened, how it happened and about how it must never happen again. Germany speaks openly about its dark past — as long as it is not on a personal level.

On Tuesday January 18th, Germans and non-Germans were brought together by the Dart Centre at the Frontline Club in London to discuss how Germans have dealt psychologically with their country’s complex history.

The event was co-sponsored by the German Embassy and opened with the showing of Thomas Reimer’s film "Meine Schlachtfelder" ("My Battlefields"), first broadcast in Germany in November 2002.

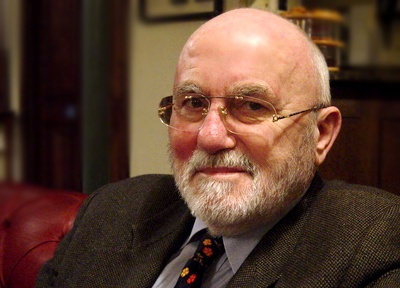

Reimer was born in 1936 in Berlin, studied war history and became a TV journalist, working for many years as a correspondent for Suedwestfunk in Vietnam, South America and Geneva.

After his retirement at 65, and reflecting on his professional past as a war correspondent, Reimer increasingly realised how much he was personally influenced by the consequences of the war.

As a child, he had stuttered and suffered from chronic headaches, and only now, he says, does he realise that these symptoms were the result of his own post-war trauma. After two years of research, he decided to tell his own story in the hope that it would encourage others to reflect on theirs.

In his film, Reimer interviews war victims, ex-soldiers, women who “cleaned up” hundreds of bodies, as well as children and grandchildren of the war generation who said the war was something that was never spoken about and who feel that a part of their history is missing.

All these people, whether directly involved or dealing with second-hand experiences, were traumatised in different ways. Not speaking about what they went through has made matters worse, or in the words of Reimer’s film: “Silence creates myths. It has longer-lasting consequences than destruction itself.”

Today, the Wehrmachtsauskunftsstelle in Germany, a data archive with information about people who served in the war, receives about 200,000 requests every year from the German public. They come predominantly from young people who wish to find out more about their grandparents’ involvement in the war. A dialogue between the generations is slowly starting to take place.

But why did it have to take over half-a-century to be able to open up this dialogue, and enable Germans to face their past?

Reimer offered the explanation that the children of the war had wanted to spare their parents’ feelings and never asked what happened. They were only too aware that the older generation’s wounds were too fresh and their memories too horrible.

Equally, the parents did not want to inflict their psychological baggage on their children, who had their own history to understand and work on. As a group, the student generation of 1968 had asked questions in what Reimer called an aggressive and accusatory tone, but that had caused their parents to become more reluctant to talk.

Said Reimer of those years: “There was no understanding, but blame.”

In a spirited discussion following the film’s showing, Michaela von Britzke, a London resident for 30 years, raised the issue of “secondary guilt”. She said she had always felt ashamed to be German, and it had been her inability to deal with that which had prompted her to emigrate to England.

Nadine Jurrat, of the Rory Peck Trust, belongs to the second post-war generation, and agreed it was sometimes frustrating to be a German abroad. It was time, she said, to break taboos involving German national pride and make a fresh start in expressing political opinions.

“I want to be able to travel the world without my head hung low because I am a German,” she said. “I am proud of being German.”

Within her family, said Jurrat, she could ask her grandparents questions that would receive an honest answer. But the same questions from her parents would in the past have gone unanswered. She suggested that people do find it easier to discuss the subject today, because time has created distance.

But much still depended upon the families’ particular role and involvement in the war.

According to Peter Heinl, a German psychotherapist consulted by Reimer in the making of his film, war children in Germany were traumatised themselves and lacked the psychological knowledge to break the silence and confront their parents.

Germany’s past is difficult to understand, and there are questions that are repeatedly being asked by those who were not involved: How could it happen? How could human beings act like this? And why was the German public unable to provide resistance?

Why everything happened the way it did is not an expression of the characteristics of the German race but of human beings in general, said Karin-Marie Wach, a psychoanalyst who cautioned against any underestimation of the influence of fear.

Based on understanding and learning from the past, what is needed now is a continuation of the debate and forward-looking initiative. Providing guidance with his film, Thomas Reimer has handed this task to the next generation.