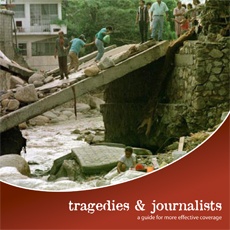

Tragedies & Journalists

A 40-page guide to help journalists, photojournalists and editors report on violence while protecting both victims and themselves. Click here for Ukrainian and Vietnamese translations.

September 11, 2001.

April 19, 1995.

Everyone knows what happened on the above dates. But you may remember others, too: The day of the storm that killed many people in your area. The day of the fire that killed innocent children. The day that someone murdered someone you knew.

Reporters, editors, photojournalists and news crews are involved in the coverage of many tragedies during their lifetimes. They range from wars to terrorist attacks to airplane crashes to natural disasters to fire to murders. All having victims. All affecting their communities. All creating lasting memories.

The events of April 19, 1995, and September 11, 2001, are slowly beginning to change newsroom cultures. But to cover any large tragedy effectively, journalists must consider three important areas:

The victims. Their deaths or injuries create a ripple effect of grief.

After the Oklahoma City bombing, Ed Kelley, then managing editor of The Oklahoman, told the staff that the tragedy was No. 1, a people story.

“Many of these people who died were much like us,” he wrote in a newsroom memo. “They lived good and useful lives. The children who died alongside them had as much potential as well.”

The community. The way journalists cover the event probably will affect how a community reacts in the aftermath of the tragedy.

Chris Peck, president of the Associated Press Managing Editors, told the APME convention on October 11, 2001, in Milwaukee:

“Our newspapers helped this nation understand what had happened in New York and Washington, D.C. Our newspapers served as the common ground where citizens came to learn about a tragedy and to share their concerns, compassion and coping skills.”

Peck, editor of the Spokesman Review in Spokane, Wash., added, “Our pages continue to bring communities together. Our reporters, photographers and editors possess unique and valuable skills that have helped a nation comprehend and consider complex issues and public policies.”

The journalists. No one is above having a human reaction.

Journalists face unusual challenges when covering violent or mass tragedies. They interact with victims dealing with extraordinary grief. Journalists who cover any “blood-and-guts” beat often construct a needed and appropriate professional wall between themselves and the survivors and other witnesses they interview. But after sitting and talking with people who have suffered great loss, the same wall may impede the need of journalists to react to their own exposure to tragedy.

Al Tompkins of the Poynter Institute for Media Studies wrote the following for Poynter.org on September 15, 2001:

“Reporters, photojournalists, engineers, soundmen and field producers often work elbow to elbow with emergency workers. Journalists’ symptoms of traumatic stress are remarkably similar to those of police officers and firefighters who work in the immediate aftermath of tragedy, yet journalists typically receive little support after they file their stories. While public-safety workers are offered debriefings and counseling after a trauma, journalists are merely assigned another story.”

In the future, we know that we’ll face more tragedies — more dates that will leave lasting memories for victims, communities and ourselves.

The practical tips in this booklet can help you become more effective in handling these vital areas.