Case Closed

Raped in Cleveland.

Abandoned by police.

She became her own detective.

By Rachel Dissell and Andrea Simakis • Originally published September 29, 2019

She’s in that dingy basement again. Everything is drained of color. The smell of simmering sauerkraut overwhelms her. His voice mocks her.

She hears it, over and over: “You’re not going anywhere.”

No matter where Sandi went, all this time later, she felt trapped in that man’s house. The memories came in flashes. Invasions. As she tried to grocery shop. Or babysit her grandkids. Or go anywhere in her car, the one he’d been in.

Once, she’d thought about driving that car off a pier into Lake Erie. But she couldn’t do that to her husband, her daughters, her sisters.

It had been almost two years since Sandi Fedor ran, naked and screaming, from a man she barely knew. Since she had fought him off, the bones of her nose crunching under his fist. Since she’d survived.

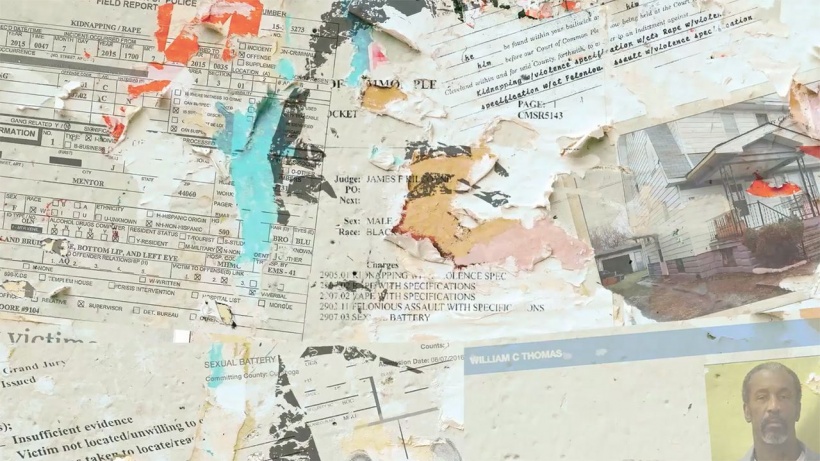

Sandi had done everything she could to lead Cleveland police to her rapist back in 2015. She’d let a nurse swab her body for evidence. She’d given a detective the man’s first name and phone number. She’d warned police he’d hurt someone else.

But police hadn’t caught him. They weren’t even trying anymore.

He was still out there. “My monster,” she called him. She didn’t know where he was, so he could be anywhere.

That meant he was everywhere.

Sandi isn’t the first woman to bring her bruised body to Cleveland police — to show up, and ask, politely and persistently as she could, for them to please do their job — only to be let down.

After they questioned her, then ignored her and forgot her, Sandi unraveled, waiting for answers that never came. And she carried the guilt when she learned her rapist had lured another woman into his basement.

That left Sandi, like so many other women, to wonder: What was wrong with the Cleveland police? Were they incompetent? Or did they just not care?

For decades, police chiefs and mayors in Cleveland have said crimes against women and children are a priority. But that has proved to be lip service. The unit that investigates those crimes is always an afterthought.

The message to serial rapists is clear: Feel free to find your next victim.

The message to victims? Ask Sandi Fedor, who found out what it’s like to be raped in a city that refuses to care.

Cleveland police had closed Sandi’s case. Hadn’t even bothered to tell her. Unless she did something, her rapist would never see the inside of a courtroom for what he did to her.

So she did what no woman should have to do. She set out to track him down herself.

Why did you do that to me?

Sandi Fedor headed into Cleveland for one reason in July 2015. To get high. She had been sober for years. But then her mom died, and she’d slipped up.

One drink at dinner became two. Then her drinking turned to drugging. Now the 50-year-old was in the city, a half-hour from her husband in Mentor, partying with one of her old friends. But the woman had her kids with her, and for Sandi, grandmother to 10, that crossed a line. You didn’t use with children around. She wanted out of that situation.

Sandi Fedor, of Mentor, is a grandmother of 10.

She tried to meet up with another friend. He was busy, so he suggested Sandi call his buddy, Will. Will would help her out.

As soon as Will slid into her passenger seat, Sandi knew she was in trouble. This guy was all bad vibes.

He was at least 6 feet tall and all muscle, with long arms and dirty fingernails. He filled the tight space of her black Ford Focus.

Did she want drugs? he asked.

“No,” she answered.

Ordinarily, she would have said yes. But something — instinct, maybe — told her that she did not want to be high on crack. Not around this man.

“I am not smoking today,” she said.

Her refusal was like pulling a pin from a grenade. “You’re wasting my time!” he yelled.

Now she was really scared. Sandi reached for her phone. He snatched it away. Without it, she had no idea how to get home.

Will yanked the keys from the ignition. The car stalled, right there, in the middle of the road. She grabbed for her keys and ripped his shirt. He threatened to throw them out the window.

The inside of Sandi Fedor's Ford Focus.

He clapped his hand over her mouth, muffling her screams.

“Shut up,” he commanded.

Just do what he wants, she told herself.

With Sandi at the wheel, they zigzagged through unfamiliar streets and construction detours. He criticized her erratic steering. “I’m not going back to jail for you!”

Everything was a demand. Turn here! Go there! To a park overlooking the lake. To a gas station where he put gas in her car. To the liquor store to buy booze.

Sandi knew she had to get away from him but didn’t know how.

Why not say it?

I.

Am.

Afraid.

Of you.

After what felt like hours, he ordered her to pull down a side street and back into a driveway between two houses.

Relax, he told Sandi. Have a couple of drinks.

Relax?

He handed her the bottle he’d bought earlier. If she drank, she could go. That’s what he told her. She took a few swigs of vodka. Soon, she was woozy.

Now he wanted to go into the house. She was too terrified to run.

Please God, Sandi thought. Why do I got to go in his house?

He hustled her into an unassuming two-story with grimy white aluminum siding. Will introduced her to his mother. She was old, but alert.

The woman glanced at Sandi from her perch on the couch. “Hi,” she said. The pungent odor of sauerkraut permeated the room.

Will bragged about his mother’s cooking and insisted Sandi have a bowl.

She wanted to bolt, but he corralled her down a narrow flight of stairs.

Sandi emptied the bowl Will had handed her, hoping the food would soak up the liquor. But then he told her to take another swig of vodka. And another. Sandi asked to use the bathroom.

Maybe the bathroom had a window, one large enough for her to wiggle through. She tried to close the door behind her, but he stopped her from shutting it. “Leave it open,” he said, and stood outside like a sentry.

She grasped the sides of the sink with both hands and stared into the mirror. She didn’t recognize the face, its features distorted by panic, like a woman in a horror movie.

A cold thought occurred to her: I don’t know if I’m going to make it out of here — I don’t know if I’m going to live.

Sandi walked back into the dim light of the basement.

“I’m not going to get out of here until you have sex with me,” Sandi said flatly.

“That’s right,” Will said. “That’s right.”

He told her to strip. She numbly complied, making a neat pile of her clothes — a white T-shirt, faded jeans, her bra and panties — on a low coffee table. Will had returned her phone, and she’d put it in her purse along with her keys. Everything together. Everything in one place.

He ordered her to lie on the bed. She stared up at the drop ceiling, stained with brown water marks. He climbed on top of her. She tried to push him off, but he was so heavy. When she yelled, he pressed her head into the mattress.

“Shut up,” he ordered.

It felt like it lasted forever.

When Will got up and made his way to the bathroom, Sandi seized her opportunity. Quietly as she could, she found her flip flops, purse and folded clothes.

The door was ajar. She could see him at the sink.

Go! screamed the voice in her head. Go now!

Sandi grabbed her things and pounded up the stairs, the voice still screaming: NOW-NOW-NOW!

She reached the side door and fumbled with the handle of the screen. OPEN-OPEN-OPEN!

The night air hit her naked body. She stabbed her thumb into the key fob, unlocking her car. She threw herself and everything she’d been carrying inside.

Sandi scrambled to pull the driver’s side door shut, but he was already on her. He jerked the door open.

"You're not going anywhere," he said.

Sandi jammed the key into the ignition, stomped on the clutch and used the force of her legs to pin herself back against the seat. He was not prying her loose.

She had to make noise. The neighbors had to hear. Sandi hollered and blared the horn.

He clamped his hand over her face. She felt like she was going to suffocate. Then his hand was gone and she gulped air. That’s when she felt her nose break. Sandi heard the bones crack, and an awful, otherworldly keening coming from somewhere, then realized the sound was coming from her.

He was still punching her, detonating bombs of pain in her face, as she turned the key and let her foot off the clutch.

She peeled out of the drive, the door hanging limp, like a broken wing.

Sandi drove. She had no idea where she was going.

Someone shouted at her from a car: “Your flashers are on!”

“He just raped me!” she screamed into the wind, her foot on the gas.

She blew through stop signs, a white lady with no clothes on, speeding through Mount Pleasant after midnight.

If I wreck this car, she thought, at least somebody will know, ‘Something happened to this girl.’

Somehow, she made it to her friend Tiffany’s house. When police arrived, they found Sandi sitting at a dining room table, wrapped in a blanket and sobbing so hard she couldn’t talk.

Sandi was still sobbing when medics loaded her into an ambulance. Her phone rang.

“It’s him,” she said, looking at the number on the screen.

“Answer it,” the cop instructed.

“You raped me,” Sandi said into the phone. “Why did you do that to me?”

We're gunna get you through this

The morning Sandi showed up for her interview with a Cleveland sex crimes detective, she had two black eyes, a bruised lip and a broken nose.

Cell phone photos Sandi took of her injuries in the emergency room.

It had been five days, and her head still wasn’t clear from lack of sleep and all the drugs they’d pumped into her at MetroHealth hospital: painkillers, the morning-after pill, antibiotics to protect her from STDs.

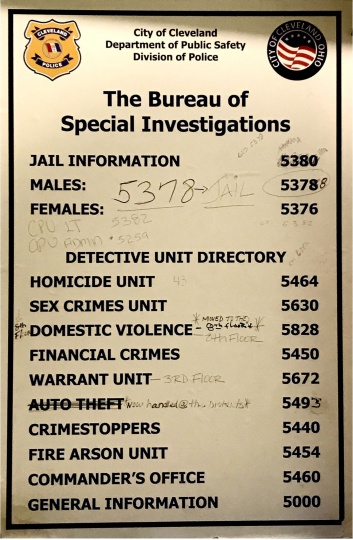

Sign on the sixth floor of the Justice Center.

But nothing was going to keep her from meeting with Detective Elaine Evans.

This guy had to be stopped before he hurt someone else.

Sandi and her husband, Gabe, made their way through a warren of gloomily lit hallways to the sixth floor.

In her blue uniform, the woman who ushered Sandi into an interview room looked more like a beat cop than a detective. But Evans had been working sex crimes cases for five years. She was promoted into the unit after 17 years of patrol car duty.

When she’d applied to the force, as a young mom not long out of the U.S. Navy, she’d said it was because she wanted to “help to keep the bad guys off the street.”

Evans told Gabe to wait outside in a children’s play area filled with sticky toys and tattered board games.

The interview felt like an interrogation almost from the start. Evans sat across the table from Sandi and turned on a video camera.

“Why was you hookin’ up with Terrance, is my question,” Evans said. “I thought you lived in Mentor. How do you know these people?”

Sandi sensed a thinly veiled subtext: What’s a white lady from the suburbs doing hanging out with a black dude on Cleveland’s East Side?

Sandi didn’t hesitate. “I do live in Mentor. I put myself in a bad situation,” she said.

“I binge — I go on binges.”

“With?” Evans pressed.

“Crack cocaine. Alcohol. I go on binges. So these are people I know through this stuff. Okay?”

Sandi started experimenting with drugs at 14. Addiction ran in her family. But she’d quit using at age 37, Gabe and her daughters cheering on her sobriety.

“I was clean for 10 years,” Sandi said. “Didn’t touch a thing.”

Then her mom died, she told Evans. The detective pointed to an engraved medallion around Sandi’s neck.

“Is that your mom?”

“Yeah, that’s my mom,” she answered, a hint of a smile tugging at her puffed-up lip. “She was my life.”

“I can tell,” Evans said.

It was during one of Sandi’s trips to Cleveland, on a binge in the fall of 2013, that she’d met Terrance. Sandi first spotted him in the garage of a mutual acquaintance, wrenching on a car. Terrance didn’t use, except maybe marijuana, and he never wanted anything from her but conversation. He was easygoing, and they just talked.

Terrance had connected Sandi to Will in a text message. He’d known him since junior high. Will would be fine to hang out with, he told her.

Terrance would know Will’s last name and where to find him. Sandi and Gabe had printed out a record of all the calls flying in and out of her phone the night she was raped, and highlighted Terrance’s number in green, Will’s number in bright yellow.

Will had called her at 1:14 a.m., as she was getting into the ambulance.

A cop even talked to him on the phone. He’d put that in his report: Will was “highly uncooperative and refused to give any information regarding the event or himself.”

“I’m going to use Terrance to help me find out who Will is,” Detective Evans told Sandi. “I’m going to call Terrance, see if I can get Terrance to come in and talk to me.”

In the 45-minute interview, Sandi took every question like a hurdle, clearing one, then moving onto the next before she lost her nerve or forgot something crucial.

In those surreal hours she had been Will’s captive — three, maybe four — he had forced Sandi to eat a meal prepared by his mother. Evans wanted to know more.

“Was it pigs’ feet?” the detective asked. “Was it good?”

Sandi paused, stumbled.

“Um ..."

The detective chuckled. “You don’t even know, huh?”

Sandi tried to sail over questions like those, ones that seemed entirely beside the point.

She told Evans she had considered not reporting the rape at all. How guilty she felt putting her family through this. How embarrassed she was.

“I’m humiliated,” Sandi said.

“Don’t be — it’s okay,” Evans reassured her. “We’re gonna get you through this ... We’ll take care of this.”

Evans rattled off the things she’d do to track down Sandi’s rapist.

“Somebody like this can’t be out there,” Sandi said. She couldn’t say it enough: “Some other girl is gonna get hurt.”

“Exactly,” Evans agreed.

“She’s gonna die,” Sandi said, her voice breaking. “Because I didn’t.”

“Exactly,” Evans said. “And that’s why we gonna get ’im.”

- Previous Section

- Next Section

Part 2: Fading from view