Case Closed

Fading from view

By Rachel Dissell and Andrea Simakis • Originally published September 29, 2019

There is Sandi Before

and Sandi After.

Sandi Before could talk to anybody — black, white, rich, poor, celebrities or nobodies. On a trip to Nashville, she found herself schmoozing with band members from the Southern supergroup Alabama like they were neighbors from down the street.

The old Sandi was game, willing to try anything. One roller coaster was never enough — she had to ride them all, until she lost her voice from screaming. Once, she ferried a coconut cream pie to a picnic while balanced on the back of Gabe’s bike.

In family photographs, Sandi Before opened her arms wide, taking in all the world had to offer.

In one of Sandi’s favorites, she’d persuaded her mom to strip down and join her in a giant bubble bath, where the two women giggled and posed like girlfriends in a rom-com.

“Nana’s just a big kid,” Sandi would remind her grandchildren. If they passed a playground, it was Sandi who couldn’t resist the slides.

Sandi took a childlike joy in the simplest things. She dressed in ruffles and bows. Maybe that was because her own childhood had felt so short.

Sandi and her mother Winnie Mae.

Winnie Mae resettled in Ohio, remarrying a kind man whom Sandi called “Pappaw.” But her mother had developed a prescription pill habit to cope with her ex-husband’s alcoholism.

When her mom was zonked out, Sandi’s older sister Rhonda stepped in as a surrogate parent, making Sandi, the baby of the family, dinner and taking her to school. She’d even drag Sandi along on dates.

It wasn’t all bad; there were lots of good times, too. But some of the bad times left scars.

An older cousin was killed after an argument in a West Virginia pool hall when Sandi was just 14. It was around that time that she first tried drugs with her sister Patsy.

When Sandi was in her 20s, another cousin, Sonja, was murdered in her off-campus apartment in Gainesville. The 18-year-old freshman at the University of Florida was one of five murdered in a killing spree that temporarily shuttered the school and terrified college students and their parents from coast to coast. The serial killer decapitated one of his victims, leaving her head on a shelf.

Horrors like that taught Sandi an early lesson: Monsters didn’t exist only in bad dreams.

Sandi on the back of her husband Gabe's motorcycle.

Sandi didn’t cry about what had happened, except when she thought of Gabe, walking into her room in the hospital. Her solid, sturdy husband had taken one look at her battered face and had to grab her bed to steady himself.

They’d started dating when she was “pushing 30,” as Gabe liked to needle her. They married in a no-fuss Vegas wedding at the Tropicana Hotel’s Island Chapel. Who wants to spend $14,000 on a wedding when you can say ‘I do’ for $400, they’d figured.

Gabe earned a decent living as a draftsman and freelance photographer. With the extra money Sandi brought in cleaning houses, they were able to afford the rustic two-story in the suburbs with a backyard so generous you could eat breakfast without someone next door peering into your kitchen to see if you took jam on your toast.

The house was big enough to offer Sandi’s aging mom the spare bedroom. Although she hadn’t always been there for Sandi, Winnie Mae beat her addiction in time to be a real grandmother to Sandi’s girls.

Their bond had grown stronger when Sandi, inspired by Winnie Mae’s sobriety, sobered up, too.

But Winnie Mae never moved in. She was 74 when she died in 2011. Sandi put her mother’s things in the spare bedroom anyway and referred to it as “Mom’s room.”

She started drinking again to numb the pain of losing her mother. She was even more crushed when she found her mom’s cursive words scrawled in a family memory book professing her pride that Sandi had overcome her addiction.

Sandi, trim, with perfectly straight black bangs, was as high functioning as it got. Her mania for order had inspired her to start her cleaning business. A way to put her OCD to good use, she joked. Her cream carpets were so spotless they looked new, even after the appearance of Sweetie, a longhaired Shih Tzu Sandi inherited from her mom.

She’d go on solitary, 5-mile walks through her woodsy neighborhood, Sweetie, sporting a “man bow” atop his head, greeting her when she got home.

Sandi would go on binges in the city, then come home to her well-organized life — “get her ducks in order,” the old Sandi used to say. Even her addiction was tidy.

Gabe hated it when she’d disappear for a day, sometimes two. He worried when he couldn’t reach her. But he’d stood by her through it all.

And Gabe was still there, living with the fallout of his wife’s rape, feeling her helplessness.

Photo Sandi took as her injuries healed.

Sandi would replay their conversation in her head. “It’s OK …” Detective Evans told Sandi. “We’ll take care of this.”

Still, Sandi worried. She remembered how she felt when Evans left her in that interview room and a Cleveland Rape Crisis Center advocate came in to talk to her.

“They’re trying to figure out if you’re telling the truth,” the woman explained. “But I believe you.”

The therapist Sandi later saw at the rape crisis center urged her to give the police time to work the case.

But time wasn’t healing Sandi.

Sandi on a family trip to Niagara Falls.

Once the cutup in all those pictures, Sandi now kept her arms pinned to her sides.

It was as if her body had become a sort of antenna that picked up signals that reminded her of him. Men with the same height or build. Men wearing the same clothing. Was it him pushing the shopping cart rolling up behind her? Was he around the next corner at the mall? Sometimes, she couldn’t leave the house.

She tried to keep working, but eventually stopped because she couldn’t stand to be alone in somebody else’s house.

They had to pay the bills on Gabe’s income. And there were more costs coming. She’d had trouble breathing ever since Will smashed her nose. Doctors told her she’d need at least one surgery.

Now, she logged miles on her indoor treadmill.

She never knew when something — the blare of a horn, the sound of a voice, cleaning behind the door in a bathroom — would trigger a flashback. Sandi called them her “episodes."

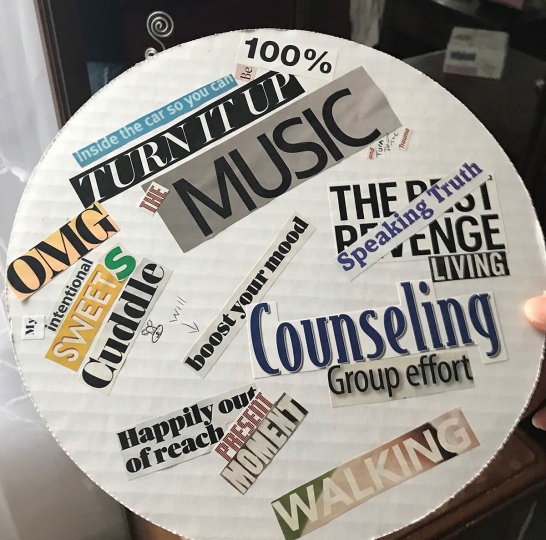

She’d run to the sink and plunge her hands into cold water or rummage in her purse to find a peppermint to pop into her mouth, sensory circuit breakers to keep her tethered to the here and now.

If she was in the car, that was harder. He’d been in the car.

They couldn’t afford to get rid of it. They’d only had the Focus for a year and a few months before Sandi’s attack. She started calling it The Rapemobile. Every time she and Gabe climbed into it, they had a fight.

The longer she heard nothing from Detective Evans, the more Sandi Before faded from view.

“I miss the old Sandi,” Gabe said.

Why didn't they do their jobs?

Sandi was afraid if she called Detective Evans too much, she’d annoy her and the cop might not investigate her rape.

When she did leave phone messages, she’d apologize for bothering her.

Early on, Evans had reassured Sandi: I’m working on the case.

And at first, it appeared she was. She made sure Sandi’s car was dusted for fingerprints, sent her phone to be examined and drove around with her to look for the house where she was raped.

Sandi didn’t hear much after that.

What about the phone numbers? For Will? For Terrance? The ones she and Gabe had highlighted.

Sandi wanted to interrogate the detective.

Did you call Terrance? Sandi asked.

I did, Evans said. A man answered. He said I had the wrong number.

Sandi asked about Will’s number.

Disconnected, Evans told her.

Sandi didn’t quite believe the detective. But she didn’t say anything.

Eventually, Evans stopped returning her calls.

Maybe Evans had decided she didn’t believe her. Maybe she’d written her off as just another crackhead, Sandi thought.

Finally, in the fall of 2016, more than a year and a half after her rape, Sandi couldn’t take it anymore.

Her therapy sessions at the rape crisis center were Sandi’s lifeline, and she worried they were about to end. The center had already allowed her more than the usual 12 free visits because Sandi’s trauma symptoms were so severe and her case was in limbo.

The following week, the therapist had an answer.

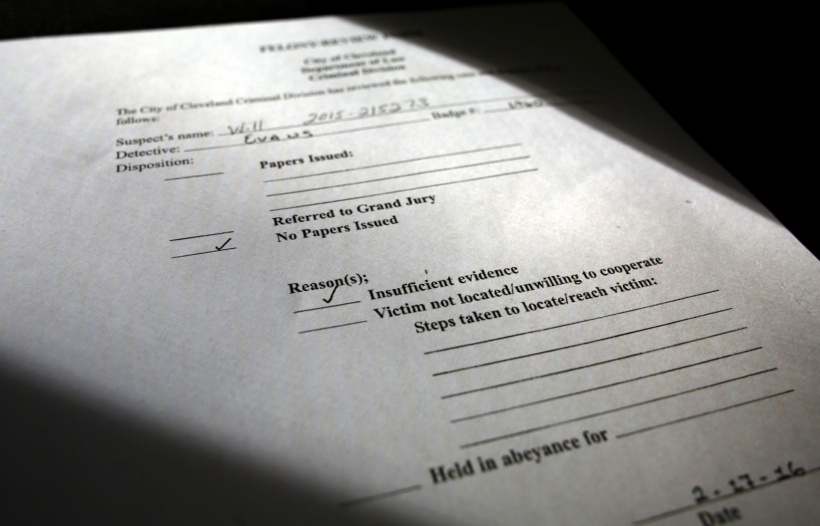

Cleveland police had closed Sandi’s case more than six months earlier.

I’m so sorry this is happening, her therapist said.

As she heard the words, her chest tightened. She couldn’t breathe. How could that be true? She had trusted the police to help her.

I gave them everything I had. Why didn’t they listen? Why didn’t they do their job?

'Dirty little secret

The department Sandi believed had turned its back on her had been doing the same thing to women for decades.

Anthony Sowell lived in a house on Imperial Avenue and where he killed 11 women and raped at least four others. The home he lived in was razed after his trial.

Anthony Sowell raped women, murdering 11, and Cleveland let him.

Rapists often pick women who have drug, alcohol or mental health issues, knowing that their stories will be doubted or dismissed.

Sowell counted on a tepid police response, and he got it. He relied on rape reports not being investigated, on victims not being believed. Sowell walked out of jail days after one woman flagged down a cop car. She’d escaped from his home, leaving a trail of blood in the snow. A detective had decided the woman was “not credible” without looking up Sowell’s record or reviewing the officer’s reports.

Sowell killed six women after that.

Community outrage over the mishandled cases prompted a mayoral commission, a 900-page report and so many promises.

Mayor Frank Jackson, elected to his second term in 2009 as women's bodies were still being unearthed from Sowell’s yard, vowed to make every suggested reform, more than two dozen of them.

Mayor Frank Jackson listens at a news conference on Nov. 3, 2009, announcing that additional bodies were found in Anthony Sowell's home.

Cops in the unit got cellphones. Other easy, aesthetic fixes were made, like painting the run-down sex crimes offices. But the larger, more systemic problems persisted.

Taxpayers also paid for the city’s negligence, though police never admitted wrongdoing. As part of a settlement, Cleveland shelled out $1 million to the families of six women killed after Sowell was released from jail. And this July, after an eight-year court battle, the city settled with two women who survived Sowell’s attacks for a total of $300,000.

Women’s rights groups and victim advocates across the country had started pushing in the 1970s for better treatment of women who reported sex crimes.

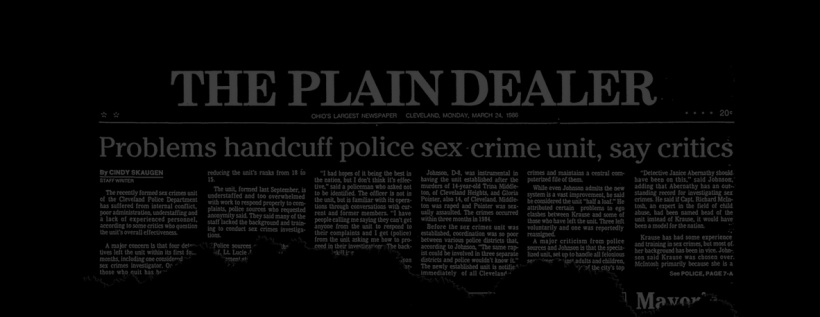

In Cleveland, members of the newly formed Cleveland Rape Crisis Center set their sights on creating a special citywide unit to investigate sex crimes but only gained political traction after an alarming increase in violent crimes against women and children, including the rape and murder of two teenage girls in the 1980s.

“Whereas, because of the large number of stolen cars, the Police Department has responded by establishing a car theft unit, yet for violent sex-related crimes against women and children, no such specialized unit exists.”

The sex crimes unit’s first manual instructed detectives that “victims will be treated as you or a member of your family would like to be treated in similar circumstances.”

But almost from the start, the squad was starved of the resources it needed to carry out that charge.

By 1988, the unit’s ranks had been slashed by half. Then, as sex crimes reports spiked, yet another detective was pulled, to serve as a chauffeur to then-Council President George Forbes.

Meanwhile, the ranks of the auto theft and narcotics units grew.

Then-Mayor George Voinovich told The Plain Dealer that he expected that the unit would be “beefed-up” after the graduation of the next police academy class.

Yet, 13 years later, a different mayor made the same promise.

In 2001, fellow detectives discovered one of their own had shoved 51 rape case files, all with named suspects, in a drawer where they sat uninvestigated, leaving victims hanging and suspected rapists free. A year later, Mayor Jane Campbell vowed to add cops and train them better.

One of the county’s chief prosecutors said the problem in the unit ran deeper than one bad apple. The quality of investigations had plummeted because there was an avalanche of cases and too few people to work them.

“For a long time,” he said, “Cleveland’s sex crimes unit has been a dirty little secret.”

But it wasn’t really a secret then, and it isn’t now.

- Previous Section

Part 1: Sandi reports her rape - Next Section

Part 3: How do I find him?