The Children of Central City

This comprehensive series offers a ground-level view of the effects of violence on children and their families, showing not only the psychological toll on young souls, but also the success stories, and scarce resources that are available to help. Judges described this package as a "brilliant body of work" comprised of a "thoughtful mix of beautifully executed stories." They recognized the "tremendous thought and planning" that went into the project, and the "incredible level of trust" the reporters built with the community after initially encountering much skepticism. Originally published by NOLA.com | The Times Picayune in June 2018.

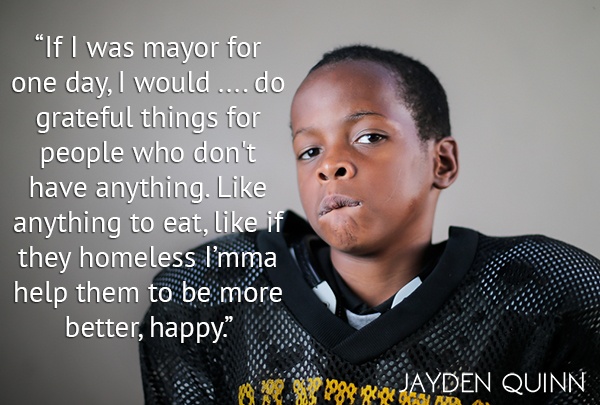

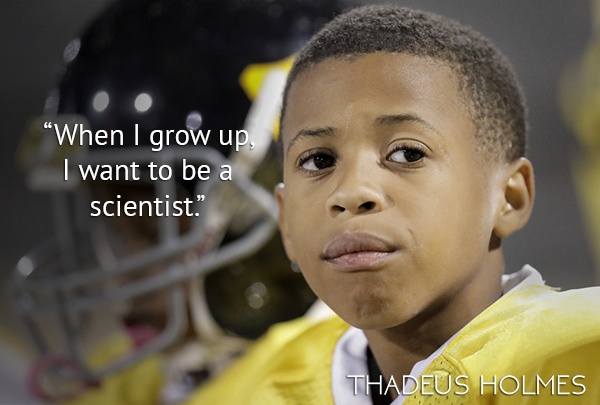

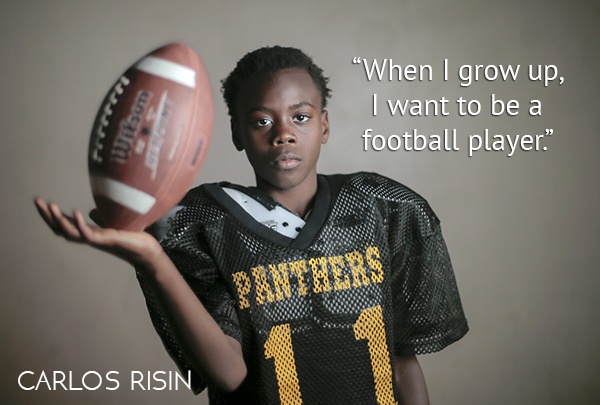

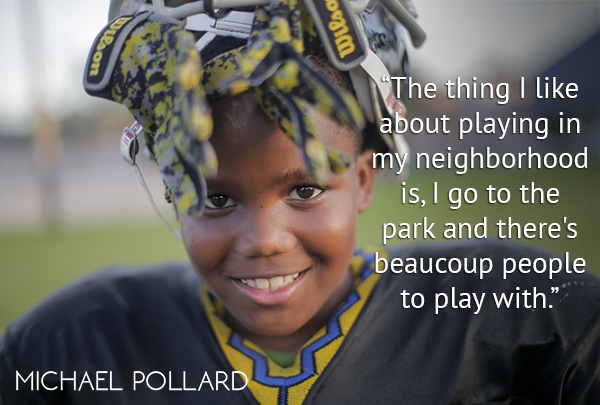

“The Children of Central City” shows how repeated exposure to violence alters a child’s brain development and other systems in the body. It examines how the city’s fractured network of independent charter school operators tries to balance the need to address student trauma with the pressure to meet state benchmarks for test scores. It also shows how lawmakers’ decision to reduce — or in some cases eliminate — mental healthcare services for children gives their families limited options for care, and leaves a handful of qualified providers struggling to meet the demand. Finally, it gives voice to those affected most: the Panthers players, who share in their own words what they want for their city, and for their futures.

SERIES ELEMENTS:

Project: The Children of Central City

Documentary: The Children of Central City

The 28

The Science of Trauma

Treating Trauma

Malachi's Story

Stolen Focus

A Tested Leader

A Family Team

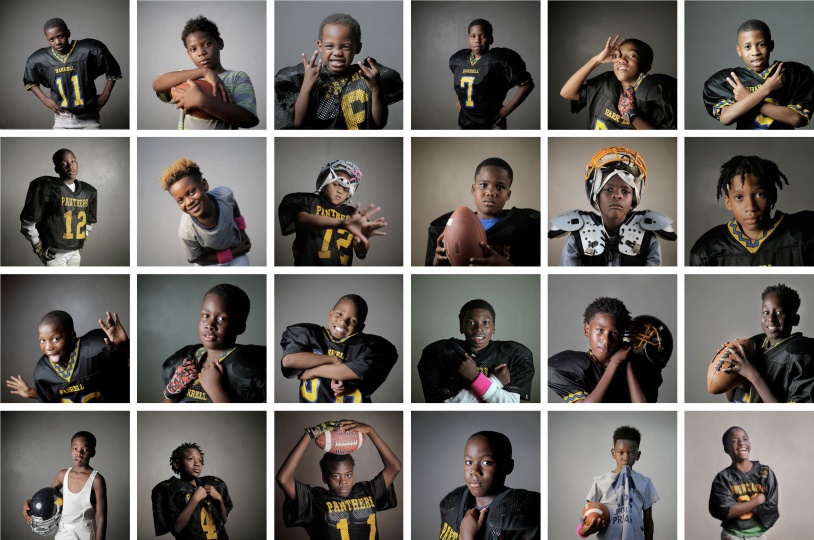

Meet the Players

One in a Million

Stories: Jonathan Bullington and Richard A. Webster

Photos: Brett Duke

Videos: Emma Scott

Graphics: Dusty Altena, Jen Cieslak, Frankie Prijatel

Design: Haley Correll, Valeya Miles, Ray Koenig

Editors: Manuel Torres, Carolyn Fox, Mark Lorando

Produced as a project for the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Project: The Children of Central City

It’s 6 p.m. at Central City’s A.L. Davis Park, and coaches Edgarson Shawn Scott and Claude Dixon have managed to corral the 9- and 10-year-old boys into something resembling a straight line.

With a piercing blow of his whistle, head coach Scott starts the Panthers football practice. The players run a lap from light post to light post. Their cleats kick up the dirt patches some say are a leftover from the days following Katrina, when the field was blanketed by limestone and 69 FEMA trailers.

Scott’s gaze quickly shifts to the nearby basketball court pavilion, and then back to his team.

“I’m looking for those boys with the guns,” he later says. “I’ve always got to keep my eye over there to make sure my kids are safe.

For the boys on the Davis Park team, it’s not a matter of if they’ve been exposed to violence – it’s how often. In their young lives, they’ve already attended funerals for slain family and friends, and stepped off school buses to the sight of flashing blue lights and yellow crime scene tape. They can tell the difference between fireworks and gunfire, and they know what to do when they hear the latter.

Violence has forever altered the lives of the team’s players, coaches and families. Among them is Ji’Air Luckie, 10, whose mother was shot dead in her kitchen while he and his older brother slept a room away.

There is 8-year-old Earl Watson Jr. who, four years ago, witnessed a woman fatally shoot a man in a Central City restaurant parking lot.

There is head coach Scott, who as a child lost his older brother and his best friend in separate shootings 12 years apart.

The losses stretch back through past Panthers teams. Twenty-eight former players have been killed in a 14-year span; dozens more who turned to selling drugs spent time in prison.

Last fall, NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune reporters followed the A.L. Davis Park Panthers. They attended practices and games, interviewing players and their families as part of an examination into an often-overlooked public health crisis: chronic exposure to violence and its devastating effects on children.

Last fall, NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune reporters followed the A.L. Davis Park Panthers. They attended practices and games, interviewing players and their families as part of an examination into an often-overlooked public health crisis: chronic exposure to violence and its devastating effects on children.

The series focuses on children who grow up in Central City– one of New Orleans’ most culturally significant neighborhoods, a nurturing home to second-lines and Mardi Gras Indians, and the epicenter of the city’s civil rights movement. But the 2,900-plus children and teens who call Central City home face rates of crime and poverty significantly higher than in other parts of the city.

“The Children of Central City” details how repeated exposure to violence alters a child’s brain development and other systems in the body. It examines how the city’s fractured network of independent charter school operators tries to balance the need to address student trauma with the pressure to meet state benchmarks for test scores. It shows how lawmakers’ decision to reduce — or in some cases eliminate — mental healthcare services for children gives their families limited options for care, and leaves a handful of qualified providers struggling to meet the demand.

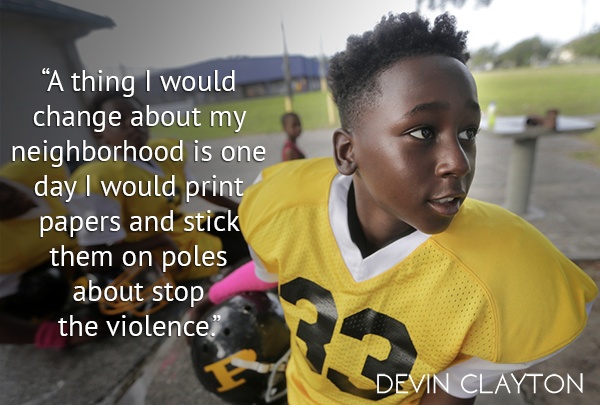

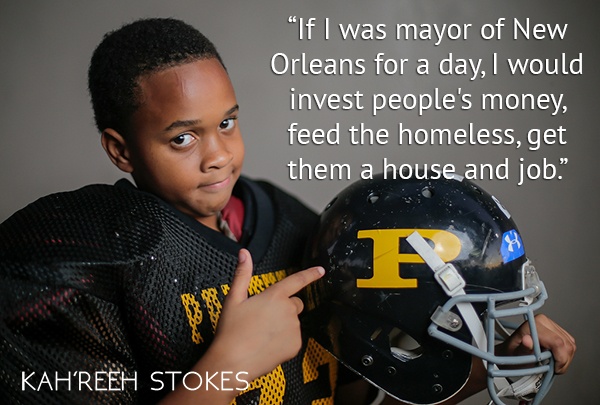

And, in the end, it gives voice to those affected most: the Panthers players, who share in their own words what they want for their city, and for their futures.

Stories: Jonathan Bullington and Richard A. Webster

Photos: Brett Duke

Videos: Emma Scott

Graphics: Dusty Altena, Jen Cieslak, Frankie Prijatel

Design: Haley Correll, Valeya Miles, Ray Koenig

Editors: Manuel Torres, Carolyn Fox, Mark Lorando

Produced as a project for the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Documentary: The Children of Central City

The movie takes you from the playing field to the classrooms, the homes of the players and the offices of the social workers whose attempts to treat the children’s post-traumatic stress are repeatedly thwarted by state budget cuts to mental healthcare.

The 28

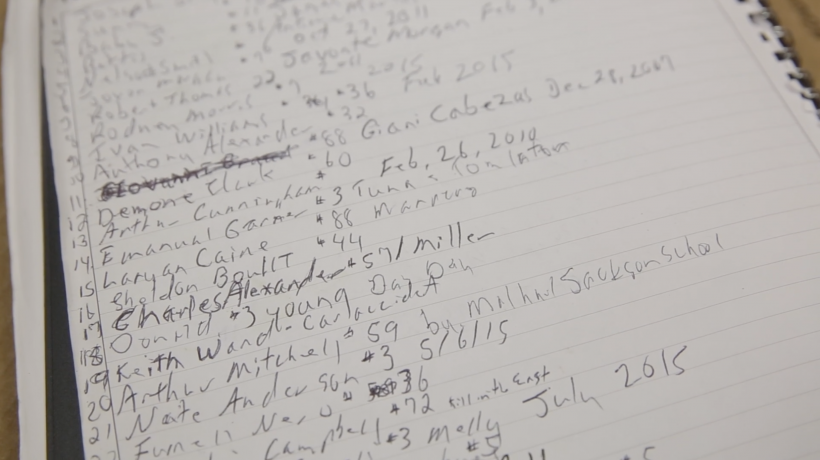

Jerome Temple pulls a tattered piece of paper out of a black binder and lays it on a table next to a yellow water cooler. There are 28 names scrawled on the single-ruled page. At the top, Temple has written, “Football players deceased.”

It’s shortly after 6 p.m. on a Tuesday in October. The sky is streaked with red and purple as the sun sets over A.L. Davis Park in New Orleans’ Central City. Temple, 52 – known to most as DJ Jubilee, an innovator of New Orleans’ bounce music – watches his beloved Panthers practice, one of 85 teams in the New Orleans Recreation Department’s youth football league.

Temple began coaching the team in 1997, when it was based in Annunciation Park in the old St. Thomas projects. The Panthers moved to A.L. Davis in 2001, after the city razed the infamous public housing development on the outskirts of the Lower Garden District.

Temple, who stopped coaching in 2016 and now works as a site facilitator for NORD, speaks with pride about his tenure with the team, during which he won eight league titles. It’s that tattered piece of paper, however, marked with the names of the dead, that Temple carries wherever he goes. It serves as a reminder that, at times, he lost far more than he won.

Twenty-eight former Panthers were killed in a 14-year span. The list begins with 17-year-old Joseph Singer in March 2003 and ends, for the moment, with 31-year-old Calvin Curtis in July 2017 – one of three former players shot to death last year.

Singer and Curtis were teammates on the 1998 Panthers, which, like all of Temple’s teams, consisted of 13- and 14-year-old boys from some of the city’s most dangerous neighborhoods.

“I started jotting their names down after the storm,” Temple says, referring to Hurricane Katrina. “My manager would call and say, ‘Jube, you hear about your ballplayer who got killed?’ I’d say, ‘Who?’ He’d say, ‘Tyrone.’ He’d say, ‘Jerry.’ He’d say, ‘Lil’ Nathan.’ All of a sudden, I end up with a list of 10 of them, then 14, then 16, 17, 18. I’m like, something ain’t right here.”

Temple has always been a true believer in football, that its regimented, team-oriented framework can instill discipline in troubled children, provide an outlet to release their anger, a family of teammates to provide a few hours of respite from whatever pain has seeped into their off-the-field lives.

For nearly two decades, this is how Temple has tried to help the traumatized youth of New Orleans, children whose mental health has been damaged by the violence that surrounds their lives. Research shows this type of trauma often prompts them to behave and lash out in risky and dangerous ways. Central City, where the Panthers practice, had the highest number of nonfatal shootings in 2016 and the third highest number of murders among New Orleans neighborhoods, according to the most recent full-year data of crime by neighborhood compiled by NOPD.

At times, Temple’s sports-driven approach has been successful. Many former players have gone on to live productive lives, crediting the support he gave and the lessons he taught them. Temple is proud of these victories, but often feels as if he is fighting without the help he needs to make a lasting difference. State funding for mental health care, for example, was cut last year by nearly $50 million, including a wide range of programs targeting children suffering from trauma.

Temple is not one to give up, but it gets harder each year, he says. He knows that if something more isn’t done to help these children, it’s inevitable that he will be forced to add more names to his list.

“You only have a small window when you can reach them,” Temple says. “All the elements out there is waiting for them, the drugs and guns and killing. All that negativity. It gets scary.”

“What is you doing?” Claude Dixon yells in exasperation, as the Panthers’ 9-year-old quarterback takes the snap, drops back three steps, then pitches the ball to an empty spot on the field. The team has been practicing the same play for nearly an hour. The results have been less than promising and assistant coach Dixon is losing his patience.

“If y’all don’t get it, y’all gonna look the exact same way as you did in the last game!” Dixon shouts, referring to the team’s first game of the season in September. The Panthers lost by 34 points.

Temple stands on the sideline, watching his protégé attempt to instill some semblance of order among the Panthers’ current roster of 9- and 10-year-old boys. Dixon’s efforts are not always successful, which is not surprising. They are, after all, just children. But immaturity alone does not explain away their lack of focus.

Many of the Panthers have already experienced horrific trauma. One player was 3 when he and his older brother found their mother shot dead on the kitchen floor. Another, at the age of 5, saw a woman shoot a man in the parking lot of a Church’s Chicken. Both players, according to their families, haven’t been the same since, suffering from stress, anger, hyperactivity and depression.

Two other players on the team are related to Telly Hankton, the notorious New Orleans gang leader serving two life sentences for murder. Another player is a cousin of Briana Allen, the 5-year-old girl shot to death at a Central City birthday party five years ago.

Scientific research has shown that early exposure to traumatic events can alter the way children’s brains work, increasing their aggression and impulsiveness, and decreasing their ability to retain information, develop empathy and build self-esteem. The resulting behavior, if unrecognized and untreated, can lead to expulsion from school and juvenile incarceration, perpetuating the cycle of violence and poverty.

Temple looks at this newly formed team of 25 boys, their small frames clad in oversized pads and helmets. Some of them, he says, remind him of his previous players whose names are forever imprinted on that mournful list. He’s seen the same story play out year after year, decade after decade, and knows that if these children are to be saved, it needs to happen now, before they get older and harder to reach.

“When you’re 12 you see it, when you’re 13 you think about it, when you’re 14, you become it,” Temple says, the “it” being the street life. “By that point, they finished playing football. All they know is weed, drugs and fighting.”

Therapy has proven effective in helping boys and girls overcome trauma. In poorer neighborhoods like Central City, however, access can be difficult. There are only a handful of reputable providers scattered across New Orleans, according to the Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights, and their resources are limited due to low Medicaid reimbursements and chronic budget cuts at the state level. This leaves many families seeking alternatives such as recreational sports, which is where Temple found solace and stability as a child growing up in the St. Thomas projects.

Like many of the players he coached, Temple was surrounded by drug dealing and murder as a youth. Gangs were everywhere, he says, ticking off their names: the Driveway boys, the Shine Street boys, the Palm Tree boys and the St. Mary boys.

“All my years in the St. Thomas, we lost (a lot of people) to murder or overdoses, and the majority were killed before 25,” he says.

Jerome Temple, also known as DJ Jubilee, talks about 28 former players on the Panthers youth football team who were killed over a 14-year period. Temple coached the Panthers for 19 years.

Eventually, that violence reached Temple’s family. All four of his brothers have served time in prison for drug-related offenses, with one confined to a wheelchair after being shot in the back. Temple says that negativity had the opposite effect on him, steering him toward more positive endeavors.

As an adolescent, he threw himself into sports, playing football in the dusty lots of the St. Thomas, outfitted in hand-me-down jerseys, “raggedy” tennis shoes and “old-time” facemasks and neck rolls. He went on to graduate from Grambling State University, after which he scored local and national acclaim as DJ Jubilee.

But Temple always returned to the St. Thomas, often times to recruit players for the Panthers youth football team – to give to others the same escape from violence he enjoyed when he was growing up.

Sitting in his office in A.L. Davis Park, Temple takes out a photo of the 1998 championship team. Three players from this group are dead, but he doesn’t focus on them. Instead, he points to a single face amid the crowded frame of 16 Panthers, a teenage boy wearing number 23, staring back intently at the camera.

“That’s ‘Air Chris,'” Temple says, referring to Chris Robinson, star receiver of Temple’s first championship team two decades ago.

Robinson was 13 when he played in the championship game, around the same time he saw his first dead body. It was a man, lying under a tree near Adele and St. Thomas streets. Robinson, now 32, says seeing that body made him feel constantly on edge, realizing that his home, the former St. Thomas housing development, was unsafe, a place where death could manifest at any moment.

“People selling drugs, that’s what I seen, night in and night out. Sex in the hallways, guns you could touch. It was tough growing up,” he says. “I used football and basketball, those were my outlets to stay away.”

There is only so much, however, that football or a dedicated coach can do. Three people on Robinson’s championship team were later killed, including his cousin who was shot to death in the hallway of a New Orleans East motel nearly two years ago. Robinson said his cousin’s name was Drontreal Beal, though the coroner identified him as Drontreal Eleby.

The problem, Robinson says, is that Temple had access to his players for just a few hours a night and only during football season. After that, those boys had to go back to whatever was waiting for them in the courtyards, hallways and dilapidated apartments they called home.

Robinson credits his own survival to strict parents and the positive example set by Temple. He currently works as a bellman at the Hilton New Orleans Riverside hotel, is set to graduate from Delgado Community College next year with a degree in business and management, and is working to establish a mentorship program based around sports called, Dreams to Reality.

Temple considers his former star wide receiver to be one of his greatest success stories. To prove his point, he takes out a team photo from 1999, the next season after Robinson’s championship. There are 41 kids between the ages of 11 and 14 dressed in the Panthers’ signature black and yellow jersey. Temple places his finger on the picture, moving from player to player, describing the fate of each young man.

“He just got killed. He’s in a wheelchair paralyzed. I don’t know where he’s at. He’s dead. He shot him. Ray back in jail. Sean got life in jail. He works at Commander’s Palace. Dig’em, he’s in jail right now. …

“I got a whole football team in Angola,” he says of the Louisiana State Penitentiary.

Temple believes that former players like Robinson can serve as role models, that the A.L. Davis Park Panthers can provide a glimmer of hope. But he knows it’s just a glimmer. He knows the problems facing many of these children run far too deep to be solved by tackling drills and championship banners.

“I try not to talk about this so much,” Temple says, looking at the 1999 photo, the faces of all those players from nearly 20 year ago staring back at him. “Our successes outweigh all this. But death is so big.”

It’s just past 7:30 p.m. at A.L. Davis Park in October and practice is almost over for the Panthers. As coaches Claude Dixon and Edgarson Shawn Scott run the team through a few final plays, three boys watch from outside the fence.

One of the boys, a husky kid, walks with a slow, determined gait through the entrance and up to the team’s water cooler. Temple motions that it’s OK for him to have a drink. The boy dips his head under the spigot, presses the button, splashes some water in his mouth, then saunters back to his friends on the other side of the fence.

“That’s one of my troublemakers,” Temple says of the 16-year-old. “He used to play for me. He quit for no reason. He thinks he’s a big baller now. Somebody’s gonna knock his a– out.”

Temple watches as the boy walks away, down Third Street towards South Claiborne Avenue, with the two other boys who are smaller, skinnier and who appear a few years younger.

“They all smoke weed. They high right now,” Temple says. The smallest of the three, a 15-year-old, also played for the Panthers.

A month after that encounter, the 16-year-old and the 15-year-old were arrested on a long list of charges including possession of a stolen vehicle and stolen property. The 15-year-old asked his attorney to call his old coach. Temple visited with the boy, his feet in shackles, at the Youth Study Center jail, then posted his $2,700 bail. The judge, however, refused to release the child until a hold on separate charges from another court was resolved.

When the judge announced his decision in court, Temple says his former player burst into tears.

“I explained to the judge how he was a good kid and I would try to save him, I would try to let him be with me for a while so far as community service, try to give him counseling,” Temple recalled later. “The judge was listening and heard my story about how many players I lost since 2003. He heard the passion in my voice, but he wouldn’t let him go.”

Back at A.L. Davis Park, as Temple watches the Panthers practice, he says he is proud of his accomplishments, but that pride is tempered by worry. He knows the odds are stacked against them.

Out of these 25 players, his experience tells him, at least half might be killed or sent to prison. But it doesn’t have to be this way, he says.

“My main thing is, we know the end result to everything that’s going on. We know who’s going to be killed, who’s going to do the killing. It’s just a matter of time,” he says. “If we don’t support these kids, do everything we can, we know what’s going to happen. So why do we let it?”

The coaches blow their whistles. Practice is over. The Panthers gather as a group in the middle of the field and pray the Our Father. “Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. Amen.”

They run into the clubhouse to take off their uniforms and equipment. Temple follows them inside, keeping watch.

The Science of Trauma

Central City is one of New Orleans’ most violent communities, with the second highest number of nonfatal shootings and the sixth-highest murder total among 20 local neighborhoods, according to NOPD statistics for the first half of 2017.

It is also home to roughly 2,900 children and teenagers, who often witness these and other crimes, such as domestic violence, assault and substance abuse. For many of the boys and girls of Central City, this is a weekly, if not daily occurrence.

Scientists, including researchers in New Orleans, have begun to understand the impact of this frequent, long-term exposure to violence. When children grow up surrounded by crime, their brains can become conditioned to perceive the world as a dangerous place, said Dr. Stacy Drury, associate director of Tulane University’s Brain Institute. As a result, the smallest provocation can trigger their “fight, flight or freeze” instinct.

In such moments, marked by high stress and fear, the body releases hormones, including cortisol and adrenaline. They elevate the heart rate and blood pressure, providing a burst of energy needed to ensure survival in times of danger. In most people, the cortisol and adrenaline levels drop back to normal once the perceived threat is gone.

This return to normal hormone levels doesn’t always happen for children regularly exposed to violence, as they live in a constant state of alarm, said Paulette Carter, president and CEO of the Children’s Bureau of New Orleans, a nonprofit mental health agency serving more than 3,000 children and their families each year. The effects can be toxic to the brain, especially those regions responsible for memory, emotions, stress responses and complex thinking.

That’s why traumatized children have difficulties with anger management, impulse control and the processing and retention of information, Drury said. Since general practice physicians typically don’t test for trauma, these symptoms can lead to a misdiagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and the prescription of unnecessary medication, causing further complications, she said.

Meet Joey. He's 9. He sees domestic abuse inside his home, and hears gunfire outside. It doesn't only scare him; it alters his body, his brain and his chances for a normal life. See how.

The full impact of trauma is not yet known, though research is beginning to show that, in addition to affecting children’s mental and emotional health, it can have a biological impact as well.

Exposure to violence can cause premature cellular aging through the shortening and fraying of the tips at the end of chromosomes, according to a 2014 study of 80 New Orleans-area children by the American Association of Pediatrics. The erosion of these protective tips, known as telomeres, can lead to cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes and mental illness, according to the study.

Trauma has also been shown to impair the immune system. When people switch into fight or flight mode, the brain shuts down parts of the body that are not vital in efforts to escape an imminent threat, such as the immune system, according to the American Psychology Association. As a result, children who exist in a persistent state of alarm and stress can suffer permanent damage to their ability to fight off diseases.

Other studies indicate that women exposed to trauma during pregnancy can pass on the mental, emotional and physical effects to their unborn child, and, in some cases, these effects can be passed on to future generations through DNA.

To raise awareness of this problem and its prevalence among New Orleans’ young people, the Institute of Women and Ethnic Studies started a campaign entitled, “Sad not Bad.” Children who are disruptive or disinterested in class, or appear prone to violence or anti-social tendencies, may be doing so not because they are “rotten” kids, but because they have been exposed to traumatic events at an early age and have not received the therapeutic care they need, the institute’s president and CEO Dr. Denese Shervington said.

“To me, violence is just the nasty underbelly of untreated trauma,” Shervington said. “If we treated trauma in children we would create communities that have psychological safety.”

Treating Trauma

Rates of PTSD soar among Central City children,

yet state budget cuts prevent access to mental healthcare

On a Sunday night in Central City in 2014, Earl Watson pulled his car into a fast-food parking lot to pick up his 5-year-old son, Earl Jr., from his godmother. As Watson got out of his car, he saw a man and a woman arguing. Within seconds, the woman took out a gun and fired twice, dropping the man.

Watson’s son sat wide-eyed in his godmother’s vehicle just a few feet away.

“The guy’s friend runs to his car, starts searching in the trunk like he’s looking for a gun,” Watson said, describing the scene that followed. “She’s standing over the dude she shot, saying, ‘I told you.’ Her daughter is in her car saying, ‘Momma, come on, he’s got a gun, too.’ She had a car full of people, little kids and everything. It was crazy.”

Watson’s son was physically unharmed. But emotionally, he hasn’t been the same since.

“If a fire truck came through with the sirens, he’d come inside running,” Watson said of his son in the months after the shooting. “He’d be crying, hysterical. His nerves are real bad. He chews off the skin to his fingers.”

In Central City, one of New Orleans’ most crime-afflicted neighborhoods, Watson’s story is not an isolated occurrence. Many Central City children have been exposed to so much violence that they show evidence of post-traumatic stress disorder in rates higher than soldiers returning from war, according to recent studies.

Most of those children and their families, however, suffer with little help. A small patchwork of New Orleans schools, nonprofit groups and healthcare agencies are cobbling together support for traumatized children, but that reaches only a small fraction of the thousands in need.

Advocates place much of the blame in Baton Rouge: Former Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal eliminated a statewide mental health care program for children 5 years old and younger. More than five years later, Gov. John Bel Edwards made cuts to drastically reduce Medicaid-funded mental health services for children of all ages.

Michelle Alletto, deputy secretary for the Department of Health, said the decision was an unfortunate necessity given the state’s $300 million deficit at the time. Edwards values mental health care for children, she said, but it often falls victim to what many view as more pressing needs.

“You can physically see someone on dialysis. You can physically see someone in hospice. You can see some physical disability,” she said. “But it’s very hard to show people mental health. Prevention is a very difficult thing to sell.”

This lies at the heart of the problem, said Paulette Carter, president and CEO of Children’s Bureau of New Orleans, a nonprofit that provides trauma-related mental health services to young people and their families. Public officials, both past and present, have failed to grasp the seriousness of the psychological injuries suffered by these uncounted victims of violence, Carter said, in addition to the long-term benefits of providing treatment.

That won’t change, advocates argue, until officials – and the public in general – understand the devastating impact of violence-induced trauma on the most vulnerable of children – impoverished, black and living in the city’s most dangerous neighborhoods.

“We have to acknowledge the fact that kids are hurt,” Carter said. “It’s easier for people to not think about those awful things, because those are hard conversations. But we have all these kids hurting, and by not helping them or trying to understand, we’re traumatizing them even more.”

On the banks of Bayou St. John, just across from City Park in Gentilly, is the Youth Study Center, the city’s juvenile detention facility. At any one time, it holds up to 48 children under the age of 16. Of every 100 children who pass through it, 96 are black.

Social worker Heather Kindschy remembers visiting one of her first clients at the jail. He was 9 years old. She can still picture him, Kindschy said, this tiny child, crying out for his mother, swallowed up by the oversized cell. She asked if there was anything she could bring to make him feel better. His reply: a Spider-Man coloring book.

“It’s always alarming to us how small (they) are,” Kindschy said as her colleague at the time, Preet Samra, nodded in agreement. “And if they’re arrested, that means they’ve been booked, had their fingerprints taken, their mug shot taken, possibly their DNA harvested. What does that teach them?”

Kindschy is a licensed clinical social worker with the Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights, the public defense agency for juveniles. Samra served in the same capacity before taking a job earlier this year with the public defender’s office in Santa Clara, Calif. Their job is to support children and their families as they work their way through the legal process. This can include providing transportation to court, making sure they are enrolled in and attending school, or arranging mental health treatment, if needed. In their experience, mental healthcare is needed in nearly every case.

More than 90 percent of the children they represent have personally known someone who has been killed, Kindschy estimates, while a slightly smaller number have actually seen someone murdered. These traumatized children often act out or exhibit troublesome behavior. Yet far too often, the solution offered by adults is to punish or lock them up, even if the alleged crime is relatively minor, Samra said.

The 9-year-old Kindschy represented had been arrested for a status offense, something that was criminal only because of his youth, such as truancy or running away from home. Only 17 percent of children in the Youth Study Center last year were arrested for violent crimes, according to LCCR.

“It’s hard for us to get (parents) to understand what trauma does and how it can affect kids,” Samra said. “A lot of parents are like, ‘He doesn’t come home at night. I just can’t control him. He just needs to go sit at Youth Study for a few days, so he can learn a lesson.’

“I don’t know how many times I can say it. Jail is not the answer.”

The answer, experts say, lies in the field of mental health care. Therapeutic techniques, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, have proven to decrease symptoms of violence-induced mental health disorders by an average of 50 percent in the first three months of treatment, according to Dr. Michael Scheeringa, vice-chair of research with the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Tulane University School of Medicine.

Cognitive behavioral therapy teaches children how to process their trauma while better regulating their thoughts and emotions through relaxation exercises and coping skills. Kindschy has seen these trauma-focused treatments at work. She remembers a young girl she represented who saw someone killed at a corner store near her home. After the shooting, the girl couldn’t walk near any corner store without suffering from severe anxiety attacks. Over time, and with the help of a therapist, she conquered her fears.

“It’s an exposure therapy. It’s really intense for kids. ‘Let’s sit down and talk about the worst day you ever had and let’s talk about it again and again and again.’ But, at the end, this girl was able to walk to the corner store and get a bag of chips,” Kindschy said.

Watson, whose son saw a man shot to death in the fast-food parking lot in Central City, arranged to have a therapist come to their home once a week. While his son continues to struggle emotionally, he is making progress, Watson said.

“I see E.J. sometimes shutting down. He gets quiet. I try to talk to him and he says, ‘I’m all right, daddy.’ But he’s getting better. I think it’s helping,” he said of his son’s sessions with the therapist. “Sometimes kids won’t open up to you, but they’ll open up to them and they might find out something we can’t. We’re just doing what we can, trying to keep him safe.”

In New Orleans, despite the overwhelming need, there are just a handful of organizations, outside of counseling in some schools, that provide trauma-focused, evidence-based therapies. These include the nonprofit Children’s Bureau of New Orleans and the state-run Metropolitan Human Services District.

Their efforts, however, are consistently undermined by state budget cuts and a lack of support among local leaders. Nearly a quarter of Metropolitan’s budget has been cut over the past eight years, and yet few people have risen to defend the agency’s mission, said its executive and medical director, Dr. Rochelle Head-Dunham.

“Look at the mayoral race. Did you hear anybody talk about mental illness as part of their platforms? Not a single one. And yet, they’re talking about all these (criminal) behaviors. Where do you think these behaviors are coming from?” Head-Dunham said.

Many traumatized children struggling with mental illness self-medicate, primarily with marijuana, to calm their nerves, Kindschy said. This puts them at greater risk for arrest, but for many it’s the only option given the state’s failure to provide mental health care for low-income families, she said.

“If you have money, if you have the means, if you have access to transportation, if you have really involved parents and you have trauma, it might not be that hard for you to be resilient and bounce back,” Kindschy said. “For other kids who have so many strikes against them and don’t have any of those protective factors, everything is more difficult.”

In June 2012, Peaches Keller’s brother was shot dead in Central City. Sixteen months later, her sister’s body was found inside an Algiers home. She had been “sliced up,” prosecutors said, strangled and beaten almost beyond recognition.

In the months that followed, Keller said her 8-year-old son Elijah, started having problems in school. He was becoming increasingly angry, accusing other children of talking about his deceased aunt. In his first few days at Good Shepherd Nativity School, he nearly got into two fights with classmates.

His mother knew he needed help coping with the losses — the entire family did, she said — so she contacted Ashley Hill, a therapist with Destined for a Change, a mental health clinic in Algiers.

Hill began visiting Elijah and his three siblings up to four times a week, both at his home and in school. They grew attached to her, Keller said, like she was a member of the family. Gradually, things started to get back to normal. Elijah was learning to better control his emotions.

Then Hill gave the Kellers some bad news. The state’s managed care organizations that oversee distribution of Medicaid dollars determined Elijah was no longer eligible for Hill’s services. He had stopped getting into fights at school and was now passing his classes; he was, in the eyes of the state, cured, Hill said.

After Hill stopped visiting Elijah, his grades once again plummeted while his behavior deteriorated.

“The school’s been having to call us for situations where he has been walking out of the class and doing all types of crazy stuff,” his mother said.

The Kellers were among the families affected when Edwards cut $49 million in behavioral health services from the 2017 budget. Faced with a $300 million deficit, the administration and legislators slashed higher education and health care, the two most-heavily funded government programs whose budgets are not protected by the state constitution and, therefore, frequently targeted for cuts.

To accommodate the $49 million cut, the state made eligibility requirements for some mental health programs more restrictive – leaving out the Kellers and many families like them.

Alletto, the health department’s deputy secretary, acknowledged that there will be “families across the state that could potentially experience a disruption in the service from a provider they’ve been seeing for a while and are familiar with.”

Hill worries about the long-term effects such disruptions will have on Elijah’s recovery, and other children just like him.

“I’ve seen how it plays out,” she said of untreated trauma. “I work with a lot of adults and they have trouble holding down a job or maintaining a stable household. The emotional trauma they experience still has major influence.”

The first step in providing help to children is to acknowledge that bad things happen to them, says Paulette Carter, president and CEO of Children’s Bureau of New Orleans, a nonprofit that provides trauma-related mental health services to young people and their families.

Paulette Carter operates Children’s Bureau of New Orleans, one of the largest providers of trauma-focused mental health care for children in Southeast Louisiana. The nonprofit has been around for more than 125 years, dedicated to waging “war against all the enemies of little children.”

In the city’s poorest neighborhoods, there is perhaps no greater enemy of children than the trauma they suffer from being exposed to violence and poverty, Carter said.

“I had a kid who came in who had bruises all over from being whipped with an electrical cord. Yeah, there is a reason why this kid is acting out,” she said.

Children’s Bureau provides therapy and crisis intervention services to more than 3,000 children and their families per year. It also provides mental health treatment to young people at the Youth Study Center through a federal grant from the Crime Victims Fund. The pilot program has proven to be a success, with 89 percent of the children showing a reduction in their symptoms.

Carter, however, doesn’t know how much longer they will be able to operate. Children with the greatest need are all on Medicaid – which accounts for 75 percent of Children’s Bureau’s budget – but reimbursement rates are so low and cover so few services, it makes it nearly impossible to stay in business.

Louisiana annually spends an average $1,933 per child in Medicaid, the fourth lowest in the country, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. The state’s Medicaid plan pays for an hour-long counseling session, Carter said, but it doesn’t reimburse clinicians for the bulk of services associated with treating children, including case management, transportation to and from homes and schools, consultations with parents, and associated paperwork.

“My least experienced staff are working with my most complex cases because that’s all I can afford,” Carter says. “I can’t afford to hire a licensed clinician that has 10 years of experience. I can only hire ones right out of school or (who) have only had a year or two of experience.”

Hiring is also hard when most experienced clinicians can make more in private practice. Carter recently advertised a post with a $50,000 salary. In two weeks, not a single qualified person applied.

Alletto acknowledges the current set-up makes it more difficult on providers.

“When you can’t pay adequately, it becomes harder to push quality and change the way you practice,” she said. “Louisiana is really behind the curve in developing a behavioral health network."

Louisiana’s substandard mental healthcare services for traumatized children can be traced, in large part, to Jindal’s decision as governor six years ago to eliminate the state-operated Early Childhood Supports and Services program, Carter said.

The program had 10 sites across the state, including one in New Orleans, that provided mental healthcare to children under the age of 6 who had been exposed to violence and were at risk of developing mental illnesses. The program, founded in 2002, also provided support services for their families.

Jindal questioned the effectiveness of these services and claimed they could be better delivered by pediatricians and nonprofits. Pediatricians, however, are not trained to diagnose or treat trauma, and cash-strapped nonprofits can’t afford hiring early childhood specialists, said Dr. Mary Margaret Gleason, formerly a co-clinical director with the program and currently an associate professor of psychiatry at Tulane University. As a result, mental health care for children under 6 nearly disappeared in New Orleans.

Joy Osofsky, professor of Pediatrics and Psychiatry at LSU Health Sciences Center, operates one of the last remaining mental health programs in the city that treat children under the age of 6. The decision to end ECSS is representative of an overall undervaluing of the work they do and the children they serve, who are nearly all poor and black, she said.

“Every time there is a shooting you’re going to hear, ‘We need more mental healthcare.’ That will last for about three days,” Osofsky said. “For too long, there was the idea that young children wouldn’t notice trauma, that it wouldn’t have an effect and they would just get over it. The evidence is just the opposite.”

While Louisiana has cut mental health services for children, some other states are adding it. Wisconsin, which ranks second to last in per-child Medicaid spending, announced a $17 million expansion this year for mental health and substance abuse treatment that would increase pay rates for medical professionals who treat low-income people, including children.

North Carolina has also revamped its Medicaid system, paying providers about $13,000 for the duration of a single child’s treatment, as long as they are utilizing evidence-based practices, says Dr. Dana Hagele, co-director of the state’s Child Treatment Program. This amount is based on an actuarial table of what it costs to provide quality care while operating a business in a way that ensures it doesn’t go bankrupt. Given the cost-benefit analysis, Hagele says it wasn’t difficult to convince state officials to make the change.

“If just 15 kids avoid a year in a psychiatric facility because they got services from our program, it would pay for the entire program,” Hagele says. “That’s just 15 kids a year. There is a cost savings. The math is a no-brainer.”

It’s time Louisiana began to look at mental healthcare for children exposed to violence in the same way: not as a luxury, but as a vital necessity, a sound investment in the future of its children, and a prudent expenditure of public dollars, Gleason said.

“Outcomes across the board improved for people who got this early intervention,” Gleason said. “It doesn’t cost that much to do the kind of services we’re talking about in young children. It provides the power of changing a life and decreasing the financial burden on society.”

Mental health providers point to studies that show the benefits of providing trauma-focused therapy. There’s the Heckman Equation by James Heckman, a professor of Economics at the University of Chicago and a winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics. It found that early childhood care from birth to age 5 has a 13 percent return on investment.

Conversely, a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated the lifetime public cost for a child exposed to violence, abuse or neglect and who does not receive adequate mental health treatment is $210,012. This reflects the costs of healthcare, welfare and the criminal justice system, in addition to future losses of productivity.

For example, in research conducted in New Orleans, 42 children at Lawrence D. Crocker College Prep screened positive for lifetime PTSD. If those 42 children did not receive adequate treatment, the CDC estimates the cost to society would rise to $8.8 million.

James Bueche, deputy secretary for the Office of Juvenile Justice, says that nearly 100 percent of the young people held in state juvenile detention facilities experienced at least one trauma that has resulted in mental health problems.

The state spends more than $53,000 a year to incarcerate one minor. Bueche said he would rather see that money go towards prevention so these boys and girls never reach any of the facilities he oversees.

“That’s where you are going to get the biggest bang for your buck, not waiting until you’re having to pay $200, $300 a day,” Bueche said.

A frustrated Carter said this is what she and others have been saying for years, but too much of their time is spent “trying to convince people that (trauma) is an illness like any other illness that needs to be treated.”

What is society’s resistance to accepting trauma as a real threat, she asks, communicating to those children who desperately need help and can’t find any?

“The message they often get is, ‘You’re not strong enough and you don’t matter enough for us to care,’” Carter said. Her organization, she added, “tries to say, ‘You do matter and we’re going to fight for you and be here for you. But you also are strong enough to get through this and to be who you want to be.’”

Malachi's Story

He was showing the same symptoms as

somebody that was in the middle of a war’

“Imagine you’re holding a beautiful flower in one hand, and in the other, you’re holding a birthday candle.”

Todd Cirillo, a trauma therapist and crisis counselor at the Children’s Bureau of New Orleans, speaks in hushed, soothing tones as he leads 8-year-old Malachi Hill through this relaxation exercise.

“Can you picture them? Now, smell the flower, breathe in deeply,” Cirillo says. “Next, blow out the candle. Get all of the air out.

“Breathe in,” he says softly. “Breathe out.”

Malachi is seated on a couch in his family home. As he inhales, he looks over to his mother sitting on a chair just a few feet away. She smiles. He exhales.

Cirillo takes out a workbook. Written across the cover is, “Malachi’s Book,” next to an illustration of Spider-Man.

“Why did we start the book?” Cirillo asks. “Why did we start working together, you and I?”

Malachi answers in a whisper. “So, we can fix the problem.”

“And what was the problem?”

Malachi pauses. “Someone was shooting at the car.”

“Do you remember some of those emotions and feelings you were having?” Cirillo asks.

“I was terrified.”

In his 18 years working with children traumatized by violence, Cirillo has seen few cases of post-traumatic stress disorder as severe as Malachi’s – and few recoveries as remarkable.

On the night of Oct. 12, 2016, Malachi, then 7, returned to his home in New Orleans East’s Walnut Square apartments with his stepfather, Josh Tattershall, and his mother, Marigny Savala. Tattershall, a New Orleans police officer, drove their car through the front entrance when they noticed a crowd of people in the parking lot.

It was unusual, Savala says. She then noticed a man staring at them. Suddenly, the man charged their car, pulled out a gun, and fired three shots, one of which hit the rear driver’s side bumper, near where Malachi was sitting in the backseat.

Savala lunged towards her son to shield him as Tattershall floored the gas and sped off, driving over speed bumps “like they weren’t even there,” Savala says. They escaped to her mother’s home a short time later, still shaken, frightened and confused as to why they were targeted.

Tattershall believes the shooting was a case of mistaken identity. Moments before the family drove into the parking lot, two men armed with AK-47s shot a man and a woman, both teenagers, in the complex’s courtyard.

The man who fired the gun at them, Tattershall says, might have been a friend of the victims, and mistakenly thought that someone involved in the earlier shooting was in their vehicle.

All that mattered, Savala says, is that her family was safe and seemingly uninjured.

But she soon noticed something wrong with her son. He couldn’t fall asleep that night and said he didn’t want to return home. In the weeks to come, Savala would watch helplessly as her son’s fear and anxiety worsened. At some point, she thought she had lost him forever.

“Do you remember what trauma was?” asks Cirillo, visiting Malachi for the first time since they successfully finished their counseling sessions, more than seven months ago.

“Would you like me to remind you?”

“Yes,” Malachi says.

“Trauma is what happens to us when someone very, very scary or something very, very sad happens,” Cirillo says. “Trauma is how we feel, like you were feeling. You said, ‘terrified.’ That was because a trauma happened. In your case, something very, very scary, right?”

“Yes,” Malachi says.

“Trauma is your heart beating very, very fast,” Cirillo explains. “You know sometimes when we can’t think clearly? That’s what trauma is, that’s how we react, how we behave after.”

Cirillo points to a page in Malachi’s old workbook that provides suggestions on how to deal with his grief and trauma. “Do you know this one?” he asks.

“To express my thoughts and my feelings about what happened,” Malachi says.

“Yes. You did a wonderful job at that,” Cirillo says. “You did such a good job at that Mr. Malachi.”

Malachi flips to the next page. On it is a picture he drew of the shooter. It shows a man with dreadlocks pointing a gun at a car.

“Did you want to skip that page?” Cirillo asks.

Malachi nods.

“Can you tell me why you wanted to skip that page?”

“Because we already talked about it.”

“And that page had what on it?”

“The scary thing.”

Malachi Hill talks to his former counselor, Todd Cirillo, more than a year after an unknown man shot at Malachi and his family while they were living in New Orleans East.

After the shooting, the dark terrified Malachi so much that he insisted his mother drive him home before sunset. If they failed, he would crouch down in the backseat of the car and start praying, pleading with his mother to assure him there was no one waiting outside to shoot him.

He stopped sleeping. In the middle of the night, he screamed his mother’s name in a panic.

He avoided anyone who had dreadlocks and, eventually, began avoiding any dark-skinned man. He never wanted to be alone, including in the bathroom. He became anxious and hyper-vigilant. He would mistake loud noises for gunfire.

“There was an incident where a child dropped a book on the floor in school and it made a really big booming sound and he freaked out and started running,” Savala says.

Malachi’s health suffered. When he returned to school, he vomited in class.

“He wasn’t sick. He wasn’t coming down with anything. It was a physical manifestation of his stress and of his fear,” Cirillo explains.

His symptoms were so severe that Malachi reminded Tattershall of a friend’s behavior after three years fighting in the war in Iraq.

“Constant paranoia, thinking somebody is out to get you, misconstruing loud noises for gunshots. He pretty much was showing the same symptoms as somebody that was in the middle of a war,” Tattershall says.

Savala felt hopeless as she watched her son deteriorate.

“You feel like there’s nothing you can do. There were many nights I would cry just hearing him freak out in his bedroom. ‘Mama can you come in my room! Sit with me until I fall asleep!’

“Someone did that to us and put that negative memory in my child’s head. And now I have to work 10 times harder to get him back to where he used to be. I didn’t know if he would ever be the same.”

When Malachi’s symptoms continued to worsen in the weeks after the shooting, his grandmother, an NOPD sergeant, suggested the family contact the Children’s Bureau crisis intervention team.

Cirillo, a member of the crisis team, has worked on some of the most severe trauma cases among New Orleans youth. He recently counseled classmates of twin blind sisters who died in a Gretna house fire and friends of a teenager injured in a double-shooting on Union Street during Mardi Gras. He also worked with a young boy and girl who were home when their mother was stabbed to death in the 7th Ward two years ago.

Cirillo says the best way to understand how trauma affects these children is to think of a time when you were driving and nearly got into an accident. In the immediate aftermath, your heart is racing, your breathing is accelerated, and your body seizes up, all of which makes it difficult to think clearly.

Now, imagine that feeling being triggered dozens of times throughout a day by loud noises or sudden movements or unexpected flashbacks to the traumatic event. As you are experiencing all of those feelings — the anxiousness and paranoia and fear — imagine sitting down and taking a math test. Or following rules. Or listening. Or functioning on a basic level. It’s nearly impossible, Cirillo says.

This is what Malachi was experiencing when his trauma therapy sessions began shortly after Christmas 2016. One of the first things he worked on with Cirillo was creating a new narrative. Instead of a scary thing happening to Malachi, it was something he survived by being strong and brave.

Next, he helped Malachi find ways to calm down when something triggered his post-traumatic stress disorder, such as the flower and candle deep breathing exercise. Cirillo also impressed upon Hill how his thoughts control his feelings and how those feelings can affect his body and behavior.

“If I think good, I feel good,” Cirillo explains.

Most importantly, Malachi learned the value in talking about his feelings.

They wrote all of this down in the workbook in which Malachi drew pictures of the “scary thing,” but also of his safe place – his grandmother’s home – and illustrations of Spider-Man capturing bad guys before they can hurt anyone.

Six months into his therapy, Malachi was making significant progress. But the real test came on the 4th of July.

Savala says she watched her son as fireworks exploded around them. At first, it seemed like he was going to panic, like he had done on New Year’s Eve. But he stopped himself and looked at his surroundings, she says. He saw that the adults were calm. No one was scared. He realized he was OK and then did his deep breathing exercises.

“It impressed me to see him use those skills, to redirect his mind from being fearful and taking charge of his feelings,” Savala says.

After seven months, Malachi, who recently turned 9, completed his therapy sessions and celebrated with a pizza party with his mother, stepfather, grandmother and Cirillo. The family moved out of the New Orleans East complex to a new home where Malachi has made lots of new friends and, once again, enjoys playing outside, long after dark.

He’s made a full recovery, his mother says. The memory of that night hasn’t gone away, but now he has the tools to manage his emotions.

“When he gets scared, he’ll tell me, ‘Mom, I had a dream about the bad guy.’ And I’m like, ‘OK, how do you feel?’ And he’ll say, ‘I feel better because I de-stressed and I did my breathing.’”

Five months into Malachi’s therapy, Savala says she saw an interview on the evening news with 11-year-old Jeremiah Smith. He had been shot in the leg during a drive-by shooting near his grandmother’s house in Central City. As she listened to the boy describe how the bullet entered and exited his thigh, Savala said she feared for his future while realizing how fortunate she was to have found help for her son.

“A lot of those children, 9 times out of 10, they don’t get the help they need and they’re just having to deal with it,” she says. “They hold all these feelings inside and they don’t have anybody to talk to about what they’re feeling or how sad they are or how afraid they are, and it is difficult.”

If Malachi didn’t get the help he needed, with the symptoms he was exhibiting, his future could have been bleak, Cirillo says. He would continue to struggle, losing sleep and becoming more anxious and paranoid. Unable to concentrate, his grades might have gone down. It’s possible he would have acted out physically, harming himself or others, leading to suspension or expulsion from school.

All the while, his family unit would gradually break down under the stress of his increasingly erratic and volatile behavior. Malachi’s trauma, eventually, could have led him to doing something truly terrible, breaking the law in some way that would have ended with him serving time in prison.

But that’s not his outlook.

“When there is a breakthrough, you can see them relax, and you can see them become comfortable and you can see them become confident and, more importantly, you can see them become a kid again, because that’s what they lose,” Cirillo says.

Sitting in the living room of Malachi’s family home, Cirillo turns back to the page in the workbook where Malachi drew a picture of the shooter.

“What do you think about this page when you see it now?” he asks.

“How he did it,” Malachi says.

“How does it make you feel?”

Malachi considers his answer. “Disappointed in him.”

“Yeah, I’m disappointed in him, too,” Cirillo says. “That’s an excellent way to put it Mr. Malachi. You’re very, very smart.”

Cirillo then has Malachi turn to the end of the book.

“There’s one last page,” he says. “Do you remember reading this? Would you like to read it again?”

Malachi nods his head then begins to read: “This is the end of my very special book. But I know I can look at it any time I want to and remember all the special things that we did. I have been very brave and talked about scary things and things that made me sad. I have learned how to calm myself down and I have learned different ways of dealing with stress so that I can feel better.”

“That is wonderful Malachi. I am so proud of you,” Cirillo says. “If you had to talk about counseling to another kid who something else has happened to, like say something that happened to you, what would you tell them?”

“Be brave.”

Stolen Focus

Trauma can have a devastating impact on a child’s education. So why have some New Orleans schools

failed to address the problem?

Three months had passed since the boys found their mother lying dead on the kitchen floor, covered in “pink paint,” as 3-year old Ji’Air Luckie described it.

In that brief span, school grades for his older brother, Jerone, plummeted. The once vibrant 7-year-old seemed to retreat into his thoughts. Ji’Air, meanwhile, “just couldn’t function,” said their grandmother, Paulette Young, 57.

“He was always wanting to know where she was, and I guess he wasn’t understanding, so he was acting out,” she said of Ji’Air.

In the immediate aftermath of 24-year-old Cierra Luckie’s killing on June 11, 2011, Young knew the boys needed more help than a grandmother could give. She thought to start at Jerone’s school, Edgar P. Harney Spirit of Excellence Academy, a few blocks from her home. She asked to speak with the school’s counselor.

“I think I need some help,” Young remembered saying. “These kids went through a trauma.”

Every day, across much of New Orleans, children come to school having been exposed to violence. Some, like Ji’Air and Jerone Luckie, witness it up close. Others see it on school bus rides past crime scenes, or hear it in gunshots at night. The trauma of those events can follow them in hallways and classrooms, stealing their focus from the day’s lessons or causing them to lash out at teachers and classmates.

Yet some educators and child psychiatrists say the city’s public schools have historically failed to address the role of trauma in students’ lives, and most remain unprepared for it, choosing to lean on overworked counselors or harsh discipline aimed at what has often been misdiagnosed as a behavior problem.

A relatively new movement among some New Orleans schools is trying to change that, by recognizing the link between trauma and school performance, and helping schools to become safe spaces where traumatized students can get back on track.

Such trauma-informed schools have popped up in school districts from San Francisco to Philadelphia. But adopting that model in New Orleans’ fractured charter school network is arduous work, hampered by a state evaluation system that ties a school’s survival to standardized test scores. It also goes against years of zero-tolerance discipline that became a hallmark of some post-Katrina schools.

New Orleans is in a unique position, with many children who “suffer chronic trauma as a result of living in this city, and it goes largely unresolved in schools,” said Jonathan Johnson, who taught in Central City for four years before starting the small charter high school, Rooted School, on St. Charles Avenue in Uptown.

“By not addressing this in our school system, we’re not preparing them certainly for success through a collegiate system, but furthermore, to take care of themselves and their families,” Johnson said. “We’re just not preparing them to live.”

Paulette Young talks about her daughter Cierra Luckie's 2011 murder and the trauma it inflicted on her grandsons Ji'Air and Jerone, who were 3 and 7, respectively, when they found their mother dead on the kitchen floor.

Ji’Air and Jerone fell asleep watching TV on the floor in the back bedroom of their mom’s Hollygrove home that night in June 2011.

The boys didn’t hear the gunshot in the next room, Young said. Neither did the neighbors. The next morning, Jerone woke up and asked his younger brother if he was hungry. They walked to the kitchen to heat up soup when Jerone spotted the body.

“Come on Ji’Air,” he told his brother, according to Young. “I think mommy’s dead.”

Young said investigators called the gunshot to her daughter’s head a crime of passion. But seven years later, the murder remains unsolved.

Traumatic events like this are all too common in New Orleans. In surveys of more than 300 students from Central City area public schools since 2016, one in five children said they had witnessed a murder, and more than half had someone close to them who was murdered, according to the Institute of Women and Ethnic Studies, a nonprofit public health organization who conducted the surveys.

A single event, like the death of a parent, can cause trauma in a child. So, too, can repeated exposure to violence, child psychiatrists say, even if the exposure is not direct. Poverty, divorce, a parent in prison or substance abuse in the home can also cause trauma.

Some children with trauma have trouble paying attention in class. They put their heads down on their desks and sleep, or break out in tears at seemingly random times. Others may appear quiet, but chew on clothing or pick at their fingernails. More outward signs may include aggressive outbursts: kicking tables and chairs, yelling at classmates or being disrespectful to teachers.

While these reactions might seem self-destructive, they are unconscious defense mechanisms constructed by the brain to ensure survival, said Paulette Carter, CEO and president of Children’s Bureau of New Orleans.

“They’ve adapted exactly the way they’re supposed to adapt,” Carter said of traumatized children. “They have learned through countless exposures they need to be primed and ready to protect themselves.”

Dr. Stacy Drury, associate director of Tulane University’s Brain Institute, illustrated the point. She worked with a child who would jump under his desk every time he heard a loud noise. Drury told the boy’s mother that therapy could stop that behavior.

“Don’t you dare,” Drury recalled the mother responding. “There’s gunfire in my neighborhood and if he doesn’t jump under the table at a loud noise he’s going to get shot.”

Trauma is often not acknowledged as the root cause of this type of behavior, some educators and child psychiatrists say. A child who can’t focus because of chronic neighborhood violence is instead diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and prescribed medicine that, according to Drury, could do little to help. That child is then sent to the principal’s office or suspended from school as a result of his or her behavior.

In the years after Hurricane Katrina, with the city’s failing public school system essentially dismantled and replaced by dozens of independent charter operators, strict discipline policies were seen by some school administrators as essential to improving both school safety and academic performance.

“You’re talking about schools that were in crisis mode post-Katrina,” said Johnson, of Rooted School. “And in crisis modes, it’s a command-drive style – what I say goes. The question becomes, to what extent are we still in crisis? If we’re not in crisis, why do we continue to operate as if we are?”

Among eight public schools in Central City, some have managed to reduce suspensions in the last four years, and others have not, Louisiana Department of Education data show. But every school except one – James M. Singleton Charter School – has a suspension rate in the last school year that was higher than the state average.

“Folks grab at the lowest hanging fruit,” said Vera Triplett, former Recovery School District deputy superintendent and current founder and CEO of Noble Minds Institute for Whole Child Learning charter school. “What’s the quickest way to remove the problem? Remove the child. Suspension becomes an option because it’s quick and easy.”

Research suggests suspensions do little to improve academic success. Instead, they disproportionately target children of color and low-income children in Louisiana and across the country, according to a 2017 report from Tulane’s Education Research Alliance for New Orleans.

“Fundamentally, I think there’s still a general belief that black children need to be punished in order to learn,” said Andre Perry, a former New Orleans charter network leader and current fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Five New Orleans schools are taking part in a trauma-informed learning collaborative launched in 2015 by the city’s health department, in collaboration with social service agencies and Tulane University’s psychology department. Initially convened three years earlier to discuss how to help after a single traumatic event – mainly, the death of a student – they soon shifted focus to also addressing chronic trauma among children living with violence and poverty.

“They were doing good clinical work … but then the kids were going back into a school environment that was far from trauma-informed in many situations,” said Kathleen Whalen, a social worker who serves as project director for Tulane’s trauma-informed schools work.

Lawrence D. Crocker College Prep just outside Central City entered the collaborative through the trail blazed by its then-principal, Amanda Aiken. Though unfamiliar with the phrase “trauma-informed schools,” Aiken said she saw anger and pain in her students – several of them with parents or siblings who were murdered.

“It wasn’t like us trying to be cutting edge or innovate. It was: We love our kids, and we see how life is stacked against them, and we know what the alternatives are if they can’t get it right,” said Aiken, who now works as chief of external affairs for the Orleans Parish School Board.

The group paired agencies with schools, to train teachers and to create individualized plans to help students with trauma – as opposed to a one-size-fit-all approach. At KIPP Believe Primary, in the city’s Black Pearl neighborhood, for example, one approach is called “Meaningful Mondays”: Once a month, a teacher spends one hour with one student, who chooses the activity for that hour while the teacher observes and participates if asked.

“It’s training teachers to give their undivided attention to the child and to communicate behaviorally and verbally that I’m paying attention to you and I care about you,” said the school’s psychologist, Patrick Bell.

Some students at Crocker, meanwhile, carry a color-coded card in their pockets, which they can pull out to discreetly show teachers they are struggling and need to take a break at the school’s teacher’s lounge-turned-wellness center for students.

While different, the themes are similar: build safe relationships, recognize subtle and not-so-subtle signs of trauma, teach coping skills for students and staff, move away from harsh discipline policies.

“Trauma-informed approaches say we’re going to change the whole system so it lets every single person who walks in the door of this building — regardless of whether they’ve had trauma or not — be successful, feel safe and be able to thrive,” said Courtney Baker, a Tulane assistant psychology professor and one of the leaders of the effort in New Orleans.

Baker and her colleagues have expanded their work with “Safe Schools NOLA,” a four-year study of trauma-informed practices in six public schools, funded by a $2.6 million grant from the National Institute of Justice.

The grant pushes the total of trauma-informed schools in New Orleans to 11. But that’s not to say other schools in the city are not doing similar work. As Bell notes, some tenets of trauma-informed care mirror those found in other social-emotional behavior models practiced for years in some of the city’s classrooms.

For the 2017-18 school year, KIPP Central City Primary started trauma screenings and counseling groups for students in first and fifth grades, in partnership with Project Fleur-de-Lis, an arm of the Mercy Family Center behavioral health clinic that provides mental health services to schools. KIPP is among a dozen-plus New Orleans schools in which Project Fleur-de-Lis offers group therapy on trauma.

Teacher development continues to be a focus as well, said school principal Theresa Schmitt, with the most recent training centered on being aware of each child’s response.

“It isn’t, ‘I’m a mean child or a bad child,’” Schmitt said of the training’s focus. “It’s potentially their default state, so how do we offer those positive experiences to kind of shift that?”

The conversation around trauma-informed schools gained traction in the late 1990s, after a study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente found a link between childhood trauma and health problems.

Trauma-informed approaches have taken root in school districts in Los Angeles, San Diego and Philadelphia, among others. In 2015, five high school students in California’s Compton Unified School District filed a federal class-action lawsuit arguing the district doesn’t address the needs of students exposed to neighborhood violence and poverty. The case is still being litigated.

At the state level, Washington and Massachusetts have enacted programs to address trauma in schools. In Missouri, lawmakers in 2016 required the state’s education department to provide trauma training to any school district that requests it, and called for a pilot study at five school districts. The Missouri law was based, in part, on the work of a commission formed after the racially charged police shooting in Ferguson.

Dr. Jerry Cox, a psychologist and member of the task force that led to the legislation, said roughly 80 schools in suburban St. Louis have already taken part in training.

“What it’s really about is supporting kids and how to help kids be emotionally available to learn, but also supporting teachers to be emotionally available to teach,” Cox said of Missouri’s efforts.

Growing trauma-informed practices in New Orleans’ patchwork of independently managed charter schools has obstacles. Unlike in traditional school districts, where policies and money are funneled from the top down, New Orleans’ autonomous charters set many of their own policies. The spread of trauma-informed schools in the city has thus far been driven by grant dollars and by pre-existing connections between social service agencies and staff at those schools.

Some say that helps spread good practices among charters within the same network, such as KIPP schools. Because KIPP has autonomy in decisions for its schools, it can do so with limited red tape, while also tailoring the approach in each school.

“If you have this big sweeping mandate they’ll treat it like that – they’ll do the bare minimum,” said Aiken, Crocker’s former principal. “A mandate can’t speak to the individual kid. It’s not a one size fits all, and the minute people try to make it a one size fits all is the minute it becomes like everything else in education: a buzz word.”

But schools without connections to the experts are missing out on chances to learn how to address student trauma.

“For the schools that are engaged with community agencies like us, they’re doing lots of great work. But there are other folks who are new in town or don’t know, and they’re on an island, which is difficult,” said Project Fleur-de-Lis director Laura Danna.

Then there’s the challenge of the state’s performance evaluations, which assigns a letter grade to each school based, among other metrics, on how students perform on standardized tests. Schools that consistently receive low grades can lose their charters. That pressure can give school administrators pause when considering whether to invest time and money on training that, at least locally, remains a relatively untested approach for student trauma.

As Crocker’s principal Nicole Boykins put it: Every moment a child spends learning how to cope with trauma is a moment not spent learning science or math that will be on the test.

That student “is a better person and she is going to be able to function,” said Boykins. “But academically she’s missed all this stuff she’s going to be tested on, because we still live in this world of standardized tests.”

Proponents argue that trauma-informed practices will help schools get better grades once those practices are given time to take hold in every classroom. Investing that time is what’s hard for some schools.

“It’s hard for schools, especially for schools where their charter is up this year, or they’re against the wire and so they’re having to make choices that are best in the short term. You’re looking at three to five years to really see progress. That’s a hard thing for anybody to sign up for when you’re on the chopping block,” said Danna.

But the biggest challenge, proponents say, is changing the mindset that harsh discipline — for years thought to curb problem behaviors and keep schools safe — is not the right approach for trauma.

“There are people who do not believe that trauma and how it impacts a child’s brain is a real thing,” said Noble Minds Institute’s Vera Triplett. “I could pick those people out in every school I went to. They think this is a bad kid and that kid needs more discipline or their parents just don’t care and they’re not doing enough.”

Still, said Triplett, the obstacles are not insurmountable.

“This is the result of a failed education system and a failed economic opportunity system,” she said. “So, now to say that the issues that adults created and caused for these kids, now these kids are on their own – that’s not the answer.”

It’s the day before Thanksgiving and Paulette Young is in her kitchen keeping an eye on sweet potato pies baking in her oven. Two rooms away, her grandsons, Ji’Air and Jerone, play video games from their beds on opposite sides of the room, while also watching YouTube clips of video games streaming on their phones.

That preoccupation with video games was one of the main reasons why, last summer, Young walked to nearby A.L. Davis Park to sign Ji’Air up for the park’s football team for kids ages 9 and 10.

“I had to pull him out of this and that,” she said, pointing to the small television and video game console at the foot of Ji’Air’s bed.

Young is among the few parents or grandparents at every practice, unfolding her green lawn chair in the shade of a tree along Third Street, where she can keep watch over the team and on the basketball court, where Jerone plays.

“What I want him to get out of it is discipline,” she said of Ji’Air playing football. “And the social part of it – being with other people.”

Young said her grandsons have come a long way since that day in 2011 when, after their mother’s killing, Young spoke with a school social worker who connected the boys with mental health counselors at Children’s Bureau of New Orleans.

Ji’Air, 10, has been on medication for ADHD, but Young says she wants to talk to a doctor about weening him off it. He still has moments of anger and frustration that seem to bubble up at random. But, taking a break from his video game, he proudly displays his report card – straight A’s – and the blue sash he earned for being November’s student of the month at Mahalia Jackson Elementary School.

Now 14, Jerone has shown improvement in school, though he still struggles with certain subjects. He keeps busy playing percussion and football. Last year, he wrote a poem about his mom’s death, entitled “My Heart.”

Standing in his bedroom doorway, with Young nearby fighting back tears, Jerone recites the poem, which begins:

Your death hit me hard

Life surely dealt me some very bad cards

Now here I sit, stuck in time

Can’t ever get you off of my mind

Hard to close my eyes

Face is wet know that I cry

Hard to get good sleep

Swimming in the water way too deep

Jerone Luckie, 14, recites a poem he wrote about his mother's death.

A Tested Leader

A New Orleans principal’s turbulent childhood

helps shape her students’ fragile futures

The drywall in their tiny shotgun was chipped and dirty and too thin to muffle her family’s fights. So, as a kid, Nicole Belt Boykins would bury her head in a book to keep the screams at bay.