Denied Justice

As dozens more women have stepped forward to tell their stories, reforms are underway in Minnesota.

She was a farm girl from Stearns County, still in high school, out on a Saturday night for what was supposed to be a double date.

Instead, she wound up alone in a car with two older boys. They lured her to a dark, empty apartment in the town of Brooten, threw her down and raped her.

She never told anyone except her best friend and, decades later, a therapist.

Now, at 71, she felt moved to tell her story after reading the accounts of dozens of other women who survived sexual assault.

“Back in those days, if you were raped you kept it quiet.” If word got out, “ ‘No decent guy,’ as my mother put it, ‘would ever want you.’ ”

To this day, when she’s alone she sleeps with a knife under her pillow.

Joan, who asked that her last name not be used, is one of almost 100 Minnesota women who felt compelled to share their stories of being sexually assaulted after the Star Tribune began documenting chronic errors and widespread failings in the way Minnesota police, prosecutors and judges handle rape cases.

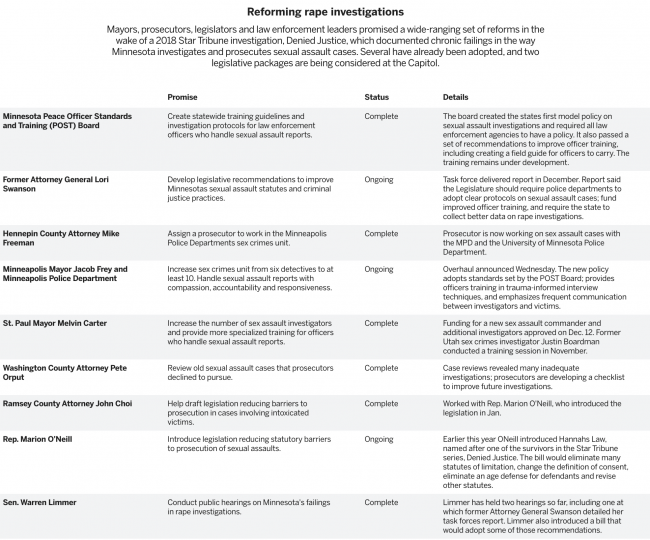

The reports, along with video testimony of dozens of women, galvanized victims of sexual violence, lawmakers and law enforcement officials alike. The 2019 Legislature will consider sweeping measures to fix “systemic failures” identified by a state task force in the way the criminal justice system handles sex assault cases. The board that licenses all police officers is recommending new specialized training and clear investigative protocols, and local police departments and county attorneys are dedicating more staff and other resources to sex assault cases.

“We have a once-in-my-lifetime opportunity to really make some changes in how these victims are addressed,” said Nancy Dunlap, an investigator at the Hennepin County Attorney’s Office and former head of the Minneapolis Police Department’s sex crimes unit. “We have to admit that what we are doing is not working and be open to a better approach.”

Kristen Houlton Shaw, executive director of the Sexual Violence Center in Minneapolis, said more women are reporting assaults and seeking assistance from her staff as a result of heightened awareness, and more people are applying to be volunteer-advocates.

Meanwhile, some of the women who told their stories have seen renewed interest in their cases. In St. Paul, Cherrelle McGowan, who said she was assaulted while on a date, learned that Ramsey County prosecutors had reopened her case and charged the man with first degree sexual misconduct. In Chisholm, police reopened the case of Katie Finch, who reported being raped by an acquaintance after an evening out with friends, and sent it to prosecutors.

Two other women, Emily Schlecht and Brooke Morath, met and became friends. They are forming a nonprofit to provide short-term housing for sex assault victims — a safe place to collect themselves after going to the hospital for a rape kit.

“We would be the first in the country as far as we are aware of,” said Schlecht.

The experiences described by the dozens of rape victims struck a familiar chord with dozens more who stepped forward to talk about how they were treated when they went to police.

“I felt like the suspect,” said Tiffany Boe, who reported being raped on her own bed in St. Cloud in 2015. The suspect denied having sexual contact with her, and police never tested Boe’s bedding for his DNA, according to records reviewed by the Star Tribune.

Many of the survivors said they had felt alone in their struggle.

“I literally thought this only happened to me,” said 29-year-old Casey Gillespie, who reported that a co-worker’s friend raped her while she was passed out in a Golden Valley apartment in 2017. A detective closed the case as “unfounded,” meaning the police concluded that no crime occurred. “I was devastated,” Gillespie said. “I felt like it was a waste for me to ever do anything.”

In a statement, the Golden Valley Police Department said investigators found video and photographic evidence to support the suspect’s account. “Detectives assigned to investigate sexual assaults,” it said “have the challenging responsibility to ask difficult questions of all individuals involved.”

Katie Hirsch described how a Minneapolis police officer laughed at her when she attempted to report her 2015 rape. He found a piece of scratch paper to take notes, she said, only when she urged him to record her account. The victim advocate who accompanied her was shocked, she recalled. She never heard from the police again.

“It was just awful,” Hirsch said.

Minneapolis police said they could find no record of a complaint filed by Hirsch, and they encourage citizens to report unprofessional conduct by officers.

Of cases reviewed by the Star Tribune, only one in four was ever sent to a prosecutor.

And when police did forward cases for prosecution, some 80 percent never resulted in the filing of criminal charges — even in cases with DNA evidence, confessions or multiple victims.

Overall, less than one out of every 10 sex assaults reviewed by the Star Tribune resulted in a conviction.

A retired Twin Cities area prosecutor described her rage and bewilderment when she found herself on the other side of the justice system in 2010. Her daughter, then only 14, was lured away from a shopping mall by a group of young men who took turns raping her in a St. Paul house. The mother asked not to be named to protect her daughter, who is still struggling to heal.

In the initial police report, her daughter recalled crucial details, including the fact that one of the rapists had a gray-colored glass eye.

She pressed St. Paul police for two years to investigate the case. The detectives never even interviewed her daughter, she said.

When she learned this year that Ramsey County Attorney John Choi was investigating neglected rape cases, she e-mailed his office. Finally, eight years after her daughter’s harrowing experience, a St. Paul police detective called. He apologized and acknowledged that more should have been done, she said.

Her daughter did not want her case reopened, she said. It remains closed.

“I am ashamed to admit this justice system, which I so dearly loved and defended, was so incompetent and negligent when my family desperately sought its help and protection,” the former prosecutor said.

Even in the rare cases that led to convictions, victims described an exhausting struggle that shook their confidence in law enforcement.

After being raped by a stranger as she walked to her Minneapolis home early on a Sunday morning in August 2015, Catherine Davlin notified police immediately. When she was alerted later that day that someone was using her credit cards less than a mile away, she called her local precinct. She said they told her it was an issue for the sex crimes unit, which couldn’t help her until Monday.

Minneapolis Police didn’t identify Davlin’s rapist, a young man named Mika Dalbec, until a year and a half later — and then only with a lucky break. Her ID turned up in Dalbec’s apartment, discovered by his landlord. By then, Dalbec had been charged and convicted in two other rapes.

Dalbec pleaded guilty in Davlin’s case and ultimately served prison time. But the court process, she said, was grueling and demeaning.

“Everything about the process was revictimizing,” Davlin told the Star Tribune. “It is completely broken.”

When asked for comment about Davlin’s case, Minneapolis Police spokesman John Elder said it highlighted the importance of treating victims with respect and skill.

“A criminal conviction without compassion, professionalism and empathy is not a complete success,” Elder said. He added that Minneapolis’ new police chief, Medaria Arradondo, plans to emphasize “procedural justice,” a focus on the way police treat people who report crimes.

Safia Khan of the Minnesota Coalition for Battered Women said the survivors’ stories, the new data and the public’s response have changed attitudes towards sexual assault and the justice system.

“It created a pivotal moment and I think in 20 years, we will look back and put our finger on this being the catalyst for a lot of change,” Khan said. “I think it’s basically created accountability in a way that we just haven’t seen before.”

A Wisconsin woman named Jennifer, who asked that her last name not be used, approached the Star Tribune with her story after reading the accounts of other sexual assault survivors.

Jennifer said she’s a mother of two, and was raped four years ago in St. Paul. She reported the assault to police, but the man was never charged with a crime.

A spokesman for Choi, the Ramsey County attorney, said prosecutors reviewed the case, including forensic evidence, and couldn’t prove that a sexual assault took place.

Jennifer said she decided to speak out in the hope that it would help others find justice.

“It’s not something I can easily talk about,” Jennifer said. “But if my story can drive any sort of change … if it can prevent this from happening to anyone else, then that’s why I’m here.”

But they also say they aren’t taking anything for granted.

Teri Walker McLaughlin, executive director of the Minnesota Coalition Against Sexual Assault, encouraged individual Minnesotans to re-examine their own attitudes toward rape and sexual behavior. That’s because victims often disclose their assault to family and friends first.

“If we aren’t doing a good job in our homes and … communities, it’s not going to even get to law enforcement,” she said. “We all need to do better.”

- Previous Section

Part 8: A Better Way to Investigate Rape - Next Section

Video: Survivors Tell Their Stories