Denied Justice

Felons spend less time in prison here, and the state says that's by design

Emma Top and Nicholas Shumaker grew up together in South Dakota and went to the same high school, both playing on the band’s drum line. She felt so safe in his presence that she fell asleep next to him in a Golden Valley motel while they were chaperoning a band trip in the summer of 2016.

When she woke up, he was raping her.

A jury found Shumaker guilty of felony sex assault in late 2017. Minnesota’s sentencing guidelines called for four years in a state prison housing other violent offenders. Instead, a Hennepin County judge gave Shumaker a year in a county jail. He was out in nine months for good behavior.

“I felt like for what he had done, he basically got a slap on the wrist,” said Top, who is now 22.

Rape charges and convictions in Minnesota are rare. Yet even when they do occur, there is often a small price to pay — especially when the assailant knows the victim.

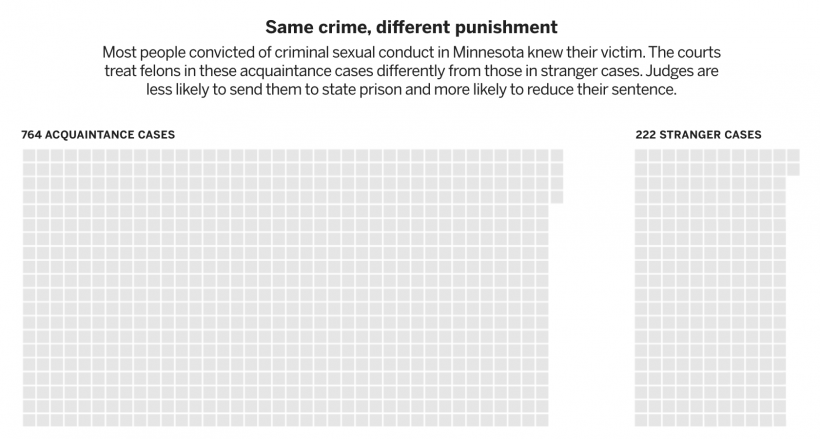

Only about half the defendants convicted of felony sexual assaults in acquaintance cases receive prison time, according to a Star Tribune analysis of state court records from the past decade. In cases where state sentencing guidelines recommend prison, offenders who knew their victims were twice as likely to receive a reduced sentence as those who did not.

Most rape victims know their attackers. In Minnesota, for example, only 7 percent of felony convictions during the past decade were for rapes committed by a stranger. Victims say lighter sentences for rapes committed by friends, former partners or others they know magnified the deep humiliation and anguish they experienced at the hands of people they trusted. Some regret ever reporting their assaults to police in the first place.

One woman, a government records clerk, was raped in 2013 by two men she knew after a festival in southeastern Minnesota. Five years later, both men pleaded guilty to felony sex assault.

Neither man spent a day in jail, records show. As part of the plea agreement, one attacker’s charge will be dismissed if he completes probation.

“I went through five years of hell for pretty much nothing,” said the 40-year-old woman, who asked not to be identified by name.

In another case, Kate, who is 28, was having drinks with friends in her Minneapolis apartment. One of the men raped her later that night after she fell asleep in her room.

Records show that he pleaded guilty in November 2017 to third-degree criminal sexual conduct, which calls for about four years in prison. He was sentenced to 60 days in a county jail and was out in about a month.

“I don’t see how knowing someone … changes what I went through,” Kate said. “He gave me a life sentence. I think about it every day.”

Giving offenders lighter punishment in acquaintance rapes only reinforces the myth that those cases are less serious, said Tom Tremblay, a retired police chief in Vermont who served as the state’s public safety commissioner. He now consults with police departments nationally on investigating sex crimes.

Other states that also rely on sentencing guidelines require much harsher minimum punishments in sexual assault cases involving penetration.

In Kansas, the minimum sentence for a rape is 12 years. In Oregon, the minimum starts at about eight years. In Minnesota, the minimum recommended sentence is about three years.

North Carolina calls for a minimum of nearly five years in prison for rape. And unlike Minnesota, judges cannot deviate from the guidelines and send rapists to a county jail instead.

Rape is “always prison” in Ohio, said Mary Katherine Huffman, a judge who presides over sex assault cases in Montgomery County, which includes Dayton.

Ohio doesn’t allow probation for rape, Huffman said. “And I don’t know that I would if I could.”

Minnesota has made a deliberate choice to send fewer criminals to prison than most states. Its sentencing laws were designed to create consistent punishments across the state, while reserving prison space for the most violent offenders, said Richard Frase, co-director of the University of Minnesota’s Robina Institute of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice.

As a result, felons in Minnesota spend less time in prison than in most other states, whether the crime is robbery, aggravated assault or rape. One reason is that keeping more people in the community, where they have ties, is likely to have a better overall impact than keeping them locked away forever, said Brad Colbert, a professor at Mitchell Hamline School of Law. “The most effective deterrent is the certainty of the punishment, not the length of the sentence.”

Less time behind bars, with more time for treatment, is also the best way to reduce recidivism, said Robin Wilson, a psychologist appointed to evaluate the Minnesota Sex Offender Program.

“Sentencing should be dispassionate,” Wilson said. “We shouldn’t let the nature of the crime lead us to potentially over-sentencing.”

But victims, their relatives and advocates are not the only ones who question the lenient sentences sometimes given to rapists. Police and prosecutors can express similar frustration.

“Probably the part that drives me the most nuts is sentencing,” said Apple Valley detective Sean McKnight. “Sometimes it’s just probation. Sometimes it’s like, ‘This is a bad human being. Why can’t you see this?’ ”

Top officials of the Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Commission said the benchmarks have been in place for years and reflect the wishes of state lawmakers.

Nate Reitz, a former prosecutor who runs the commission, said the sentencing grid for sex offenders has not changed since 2006, when it was adopted at the direction of the Legislature.

“That was their statement, that these are appropriate sentences for the typical cases,” Reitz said.

Some of the light sentences that outrage advocates — and survivors like Rachel Radford — can be traced to the original charges filed by prosecutors.

“It still puts a wrench in my stomach that I am considered ‘lucky,’ ” said Radford, who was assaulted by a friend last year.

Radford reported her sexual assault the day it happened, in April of 2017. She told a Farmington detective that she had been out having a few drinks with a friend, 28-year-old Kyle Devries, and went back to his home in the early morning hours.

Radford, 30, told police that Devries raped her after she said no dozens of times and fought him for an hour.

She texted Devries later that day: “Last night was not okay and I will never forgive you for it. … you weren’t listening to how many times I said ‘no.’ ”

“I know, I’m sorry I wasn’t thinking with my head,” Devries responded, according to the police report.

A detective examined Devries’ court record and found that he had been convicted in 2011 of criminal sexual conduct in a case involving a 15-year-old girl, when he was 19.

When Radford met with Dakota County prosecutors in January, she said they told her Devries would again be charged with a gross misdemeanor sex crime, punishable by only up to a year in jail.

“At the time I was told I was lucky it was even being charged,” she said.

Assistant Dakota County Attorney Phil Prokopowicz said prosecutors decided against felony charges “based on facts and circumstances of the case, including the relationship between the victim and defendant, combined with additional investigation performed.”

Radford said she was later told that Devries might not serve any time in jail if he took a plea deal. But in July, Devries pleaded guilty, getting a 30-day sentence. He got out in 20 for good behavior.

If he completes his two-year probation, the crime will be reduced to a misdemeanor, records show.

Devries did not respond to a request for comment.

Prokopowicz said he thought Radford was satisfied with the outcome.

“We have e-mails saying she’s extremely pleased,” he said.

But Radford told the Star Tribune that she was pleased only because she had earlier been told her attacker might escape jail time altogether.

Today, she said there are still people who don’t believe that she was sexually assaulted.

“They say if he really did rape you, then he would have gotten prison,” she said.

In Minnesota, convictions for sex crimes involving adults are rare. A Star Tribune review of almost 1,400 sex assault cases over two years found that only a quarter of the reports received by police ever get to prosecutors. Fewer than one of every 10 reports results in a conviction.

To examine how rapists are being punished, the Star Tribune analyzed sentencing data on more than 3,600 felony sex cases, involving victims age 13 and older, from the past decade. About 65 percent of those convictions were for statutory rapes, where the victim was too young to legally consent to sex. In most of these cases, Minnesota’s sentencing guidelines call for jail and probation rather than state prison.

That doesn’t mean underage cases are not serious, said Washington County Attorney Pete Orput, who is on the state’s sentencing guidelines commission. But statutory rape can be easier to prove because the suspect can’t claim consent as a defense. “It’s a bird in the hand,” Orput said. “If you think he did it, just take the statutory and get him on the [sex offender] registry.”

Of the remaining cases, the majority were rapes or sexual assaults where the assailant and victim were acquaintances, partners or spouses. About 70 percent of those cases were serious enough that state sentencing guidelines called for prison time.

However, only half the offenders were actually sentenced to prison time.

Many of the sentences came as a result of a plea negotiated with the defendant, where prosecutors could at least get a conviction in exchange for a lighter sentence and avoid the risk of losing at trial. In other cases, offenders in acquaintance rapes have little to no criminal history, which contributes to a lighter sentence.

But the less harsh sentences may also reflect social stereotypes that acquaintance rapes involve less force or violence.

“It gets written off as OK because we blame the victim’s behavior,” said Rep. Jamie Becker-Finn, a DFL House member from Roseville and assistant Hennepin County prosecutor.

Light sentences for rapes have ignited public outrage across the country in recent years. In 2016, for example, former Stanford University swimmer Brock Turner spent three months in jail for raping an unconscious woman he found behind a dumpster after a party. The judge who handed down that sentence lost a re-election bid, and California lawmakers reformed the state’s rape laws, requiring mandatory minimum sentences.

Cases like Turner’s — where a rapist is sent to jail instead of prison — happen frequently in Minnesota. The Star Tribune found 227 cases over the past decade of perpetrators convicted of a felony sex assault where sentencing guidelines recommended prison, but who instead spent less than a year behind bars in a jail.

In December 2014, for example, former St. Cloud State University swimmer Raul Navarro raped another swimmer after a party. Three years later, Stearns County Judge Andrew Pearson found Navarro guilty of third-degree criminal sexual conduct. It carried a presumed sentence of nearly four years in prison.

Pearson gave Navarro 90 days in jail and 15 years’ probation over the objection of the prosecutor, saying he was “amenable to probation.”

Pearson did not respond to a request for comment.

The victim in the case, Amber, who asked that her last name not be used, said she hopes the probation is a long enough time to make sure Navarro never offends again.

“I would’ve loved more than anything to see him rot in prison,” she said, “but for my own mental health and peace of mind I’ve had to learn to accept the sentence he received and hope that he learns from it.”

Navarro did not respond to a request for comment.

After Hennepin County charged Nicholas Shumaker with criminal sexual conduct in February 2017, Emma Top said her prosecutor prepared her for the worst. Conviction was a 50/50 chance, and to get there, Top would have to tell her story over and over again.

At trial, Top’s underwear was introduced as evidence to corroborate her description of what she was wearing that night. When Top testified, she shook and held back tears as Shumaker’s defense attorney questioned her story, trying to raise doubts in jurors’ minds about her account.

“I was so scared no one would believe me,” she said.

But the jury did, and found the 23-year-old Shumaker guilty last October.

At a sentencing hearing in December 2017, Top told Hennepin County Judge Kathryn Quaintance that being assaulted by her best friend took away her sense of security and that she felt she could no longer trust anyone.

“I didn’t sleep alone in my own bed for months,” she said while reading her victim impact statement. “I was scared of the dark, scared of being alone, scared of being in a room or house with the door unlocked. He made walking on the street exhausting.”

When Quaintance delivered Shumaker’s sentence, it stunned Top.

“The professionals in this case generally agree there is no purpose served by Mr. Shumaker going to prison, that it will not change him in any positive way, that it will not help Ms. Top,” Quaintance said from the bench.

The Hennepin County prosecutor, Sarah Hilleren, didn’t hide her frustration, shaking her head in disbelief.

Quaintance admonished her from the bench.

“Ms. Hilleren, please try to contain your displeasure at my sentence,” she said.

A month later, Top sent the judge an e-mail.

“I felt betrayed, victimized, and humiliated,” she wrote. “I felt as if I were stuck in a never-ending stereotype of society’s rape victim, and you fed right into it.”

She said Quaintance never responded.

Quaintance declined to comment for this story.

Today, Top said she’s still pained by the outcome.

“I wanted him to understand that what he did was wrong,” she said. “Instead, it felt like he got away with what he did.”

- Previous Section

Part 6: A Victim Heard, Justice Served - Next Section

Part 8: A Better Way to Investigate Rape