George Floyd Coverage

Views of the Third’s demise

The police station’s destruction is celebrated, decried, pondered

By Jennifer Bjorhus • Star Tribune • July 26, 2020

Charred, boarded up, spray painted and fenced off, the abandoned Third Precinct station sits at East Lake Street and Minnehaha Avenue in Minneapolis — stars and stripes still flying — as a nation comes to grips with what the fall of the police station means.

Home to the four Minneapolis officers involved in killing George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, the complex was a focus of the explosive protests. When it went up in flames on May 28, there was shock and disbelief.

“It was like watching your house burn down,” said retired Minneapolis Police officer Val Goligowski, who worked in the station for more than two decades.

The destruction of a police station is unprecedented in modern U.S. police history. The last time one was destroyed appears to have been in the New York Draft Riots of 1863, when a deadly race riot erupted targeting African Americans, said University of Nebraska policing historian Samuel Walker.

In interviews, people described what the fall of the Third meant to them: a deep betrayal of trust, a loss of control, a symbol of change and a breaking point.

“We’re done backing down. We’re doing rolling over. We’re done dying,” said protester Queen Jacobs.

In a 1985 Star Tribune article about the opening of the new Third Precinct building, it was hailed as state-of-the-art station, designed to be more inviting. It had skylights and an atrium and resembled a middle school. It was supposed to be a new day in policing.

“We want to break down the stereotyped police station atmosphere that people are afraid to come into,” then-Deputy Police Chief Bob Lutz said at the time. Then-Precinct Captain Al Pufahl called the new station “a symbol of law enforcement” that “says something to people who will be working in and around it.”

Today, the future of the building itself is uncertain. But what its fall meant is distinct to many.

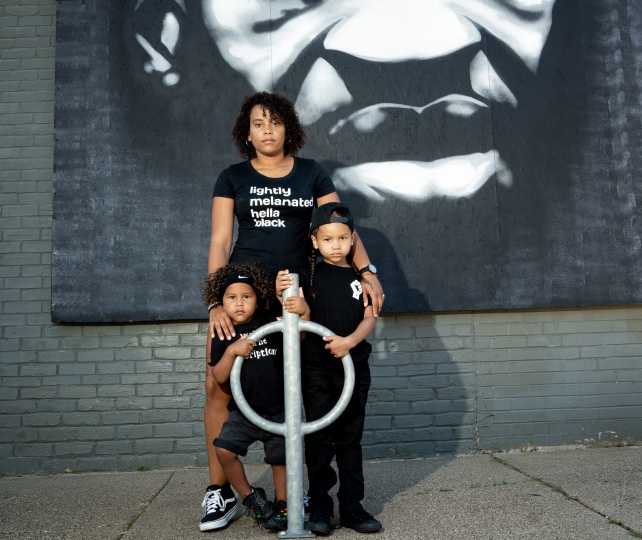

THE PROTESTER

Queen Jacobs, 26

Jacobs, a north Minneapolis swim instructor, said the killing of George Floyd moved her to protest for the first time in her life. She protested for about eight days straight, she said, getting tear gassed, Maced and flashbanged.

Queen Jacobs (with sons Alastor and Kingston) called the precinct station’s demise “liberating.”

It was about midnight, Jacobs said, when she finally got to the Third Precinct on May 28. It was already ablaze, and she stood in shock with the crowd watching the flames leap. Jacobs, who is Black, described the experience as “liberating.”

“I think we all felt a sense of strength and community, and of a piece of what our ancestors went through, and when they were able to be liberated,” she said. “We showed them, by physically removing them from what should be their safe place. We can’t go outside and be safe, so why should they be able to hide in that building with all their weapons?

“If they don’t want to hear us asking and begging to be treated like humans ... if they can’t treat us like humans ... then I am not going to be quiet, and I’m not going to peaceful, and they’re going to hear me one way or another.”

THE RETIRED OFFICER

Joey Sandberg, 55

Sandberg, a native of south Minneapolis, spent 31 years in the Third Precinct before retiring in 2018. He picked the precinct and chose to stay, he said, “to work in the community I grew up in.” He watched the station burn on television at his house.

“That was my home for 31 years. I did the very, very best I could do in police work to serve my people,” he said. “To see that go up in flames like that was very hard for me take.”

Sgt. Joey Sandberg stands in front of the Third Precinct for a photo in 2016.

Sandberg said he remains troubled by Mayor Jacob Frey’s order for officers to evacuate the precinct as protesters continued the onslaught.

“I couldn’t sleep that night. I was just fuming,” he said. “ I could not believe that the politicians would just do this. That’s not just a building to us, it’s a symbol of pride for us.”

The officers remaining at the Third that night felt completely abandoned, he said. “A lot of them feel like they were left for dead.”

“I gave my heart and soul to that precinct,” he said. “To see those people cheering and throwing rocks ... it almost seemed like all the work I did for 31 years was for nothing.”

THE RESIDENT

James Works, 47

There is no love lost between Works and the Third Precinct. Works, who is Black, is a food delivery driver who works along Lake Street. Over the years officers have repeatedly pulled him over, he said, without good reason and harassed him.

In 2017, he went to the police station to take the matter to a supervisor but was tossed out and cited for trespassing. A lawyer got the ticket dropped, Works said, and obtained bodycam footage from inside the station. It shows one officer referring to Works as an expletive.

James Works outside the Third Precinct Station.

Still, Works said the station house should not have been destroyed. He’s a veteran, he said, and feels strongly about law and order. He watched it burn from his apartment.

“Even though I have issues with the police, I feel like they shouldn’t have given up the police station,” Works said. “They should have stood their ground. Once you take down a police station, anything goes.”

“We still need to uphold the law,” said Works, who said his father is a deputy sheriff in Georgia. Works called the station house a symbol — not of authority, “but of what we stand for, like law-abiding citizens.”

Burning down a precinct doesn’t change the department’s culture, he said.

“They’re going to be right back there with the same officers doing the same stuff,” he said, and we “got nowhere.”

THE BUSINESS OWNER

Juno Choi, 41

Choi and the other co-owners of Arbeiter Brewing say they have no idea how their startup was spared from the damage. The brewery, which sits in a brick building a few doors down from the Third Precinct station, hadn’t even opened yet when the protests began.

The first two days, they stood guard. On the third, they boarded up and went home, not knowing what would be left the next day. Choi said he felt torn between protecting the business and joining in the protests.

Juno Choi said the station is now a symbol of police brutality and systemic racism.

“We don’t exactly know why our building did not burn down,” said Choi. “I think it had a lot to do with luck.”

The deserted station represents more than a Minneapolis precinct, he said. “It has become sort of symbolic of police brutality and systemic racism across the country. It was really a protest about what’s been going on all across the nation for a long, long time.”

It’s also a constant reminder now, said Choi, of why his group wanted to start their brewery: to create a gathering space for people to talk, exchange ideas and build their community. With a bit more luck, that will start happening next month, after Arbeiter Brewing’s grand opening.

THE MAYOR

Jacob Frey, 39

To many, Frey’s decision to evacuate the Third Precinct station is the moment he lost control of the city. Gov. Tim Walz the next day called the city’s handling of the riots an “abject failure.” But Frey says he’d had several conversations with Walz earlier and that the governor had never disagreed with the Third Precinct strategy in those conversations.

Mayor Jacob Frey speaks during a news conference Thursday, May 28, 2020 in Minneapolis.

“There will be things I look back on and wish I would have done differently, but the decision regarding the Third Precinct is absolutely not one of them,” he said. “If I had ordered the chief to hold the precinct at all costs, hand-to-hand combat would have been inevitable. There was a possibility of serious injury or even death.”

Frey said that he and Police Chief Medaria Arradondo were united on a strategy with three goals: to preserve life, to protect property in other neighborhoods and to de-escalate the situation. “The route we took accomplished all three,” Frey said.

“There were no good options on the table,” he said. “Imagine what would have happened to our city if either an officer or a member of the public was killed. The crisis we would have experienced would have dwarfed even what we saw.”

THE RELIEF WORKER

Jennifer Starr Dodd, 36

Holy Trinity Lutheran Church, about two blocks from the Third Precinct station, still operates the emergency relief program it started during the protests when the neighborhood lost its grocery stores. A recent Wednesday finds site manager Starr Dodd coordinating volunteers under a shade tree as families line up.

In the charred police station, Starr Dodd sees the pain and injustice people of color have experienced. She also sees hope.

“People aren’t going to be quiet anymore,” she said. “People are moving forward. They’re going to fight and protest until there is justice for all. It represents the hope to end police brutality, a clean slate.”

“I think of it as the Pentecost,” she said, referring to the Christian holiday following Easter when the Holy Spirit visited the followers of Jesus and flames appeared. “It’s like a holy anger. The spirit came and it was a great fire, and everybody changed in that moment of Pentecost. I see the burning of the Third Precinct as the same. It changed everyone, whether they like it or not.”

THE COUNCIL DIRECTOR

Melanie Majors, 53

At first, Majors, the executive director of the Longfellow Community Council, said the destruction shocked her. It wasn’t the buildings, she said. What she saw was destroyed jobs and investments, loss of access, loss of visitors to the neighborhood and a destroyed sense of safety.

“Later,” Majors said, “I thought this place [the Third Precinct station] right there made this community a target, and what does that mean for the future?

“You’ve got four officers now who have been charged, and no one knows what those outcomes are going to be,” she said.

“If there are outcomes that are really offensive to the community, and the Third Precinct is still in greater Longfellow, then that makes the area a target again. We just got past this crisis period. If we will be a target again in the future, what message would that send to those who A) want to rebuild and B) who have invested in the rebuilding?”

Majors said outrage over police treatment of Black people isn’t new for her. She said her father, who was Black, was brutalized by Minneapolis police through the 1970s. She has seen outrage come and go.

Majors said she fears that once the outrage passes, people trying to make changes will “hit the political and financial wall.”

“The symbol keeps peoples’ eyes open, but I don’t know that they provide for sustained change over time.”

CREDITS

Reporting Jennifer Bjorhus

Photography Glen Stubbe, Jeff Wheeler

Editing Abby Simons, Eric Wieffering

Design Anna Boone, Jamie Hutt, Josh Penrod

Development Anna Boone, Jamie Hutt

- Previous Section

One week in Minneapolis - Next Section

On Minneapolis' North Side, residents question calls to defund police