Gun Violence Seen Through the Eyes of Children

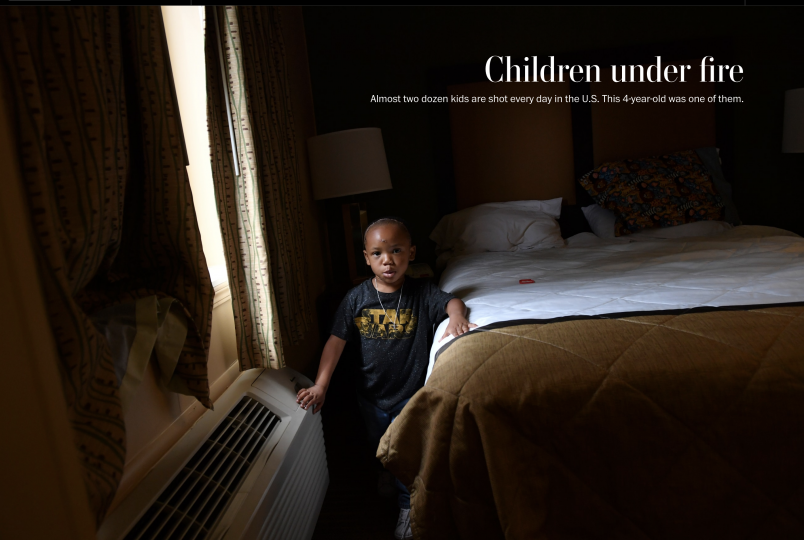

Children under fire

Almost two dozen kids are shot every day in the U.S. This 4-year-old was one of them.

By John Woodrow Cox, Originally published by The Washington Post on September 15, 2017

The bullet exploded from the gun’s barrel, spiraling through cool night air toward a gray SUV’s back passenger-side window. Carter “Quis” Hill was perched in his car seat on the other side of the glass, and as it shattered all around him, the round burrowed into his head, an inch above the right temple. From the boy’s hand slipped a bright-red plastic Spider-Man mask he’d gotten for his 4th birthday, nine days earlier.

A white Pontiac blew past, disappearing into the distance. Carter’s mother, Cecelia Hill, knew it was the same car that had been chasing them for three miles before someone inside fired eight shots at her 2004 Volkswagen in what police would call an extraordinary act of road rage.

Now she shoved her foot against the brake, squealing to a stop in the middle of Interstate 90. In the back seat, her son and daughter snapped forward against their taut seat belts. Carter’s 7-year-old sister, Dahalia Bohles, looked over at him. Shards of glass speckled her dark hair, but she didn’t notice them at first.

“Mommy, Quis got blood on his head,” the second-grader said, then she reached over and began to wipe it away.

“Stop!” Hill screamed, turning to check on her son, who, just before midnight on Aug. 6, had become one of the nearly two dozen children shot — intentionally, accidentally or randomly — every day in the United States. What follows almost all of those incidents are frantic efforts to save the lives of kids wounded in homes and schools, on street corners and playgrounds, at movie theaters and shopping centers.

For Carter, his mother feared it might already be too late.

The bullet had driven through her boy’s skull and emerged from a hole in the center of his forehead. Blood trickled down over his eyes, along his nose, into his mouth.

“Mommy, Mommy,” he’d been shouting minutes earlier, as Hill had fled from the shooter, but now her irrepressible 36-pound preschooler, with his plum cheeks, button nose and deeply curious brown eyes, was silent. He stared at her.

She faced forward and punched the gas, pushing the speedometer past 100 mph. Hill veered off an exit, stopped and leapt out of the car. She rushed to the other side and unbuckled her son, then wrapped him in both arms and collapsed to her knees.

“Help,” he heard her yell into the night, over and over, until a passing driver pulled up and called 911.

“Please don’t let my son die,” prayed Hill, a 27-year-old housekeeper at a medical clinic who had raised her kids mostly alone. She squeezed Carter against her chest.

Hill wished he would cry or scream or speak, even one word, because when Carter was happy, he chattered without pause about the most important things in his life: bananas, or “nanas,” which he could eat for any meal of the day; growing up to be the Hulk, because smashing things sounded like the best job; his sister, who was Carter’s favorite friend, even though she wouldn’t let him play with her Barbies; fidget spinners, mostly because when his mom called them “finny” spinners, it made him laugh so hard that he would hold his stomach and fall to the floor.

But there, bleeding into Hill’s blue work shirt while sirens drew closer, he still hadn’t said anything.

“Is my baby going to be all right?” she asked the paramedics in the ambulance as it sped to the hospital, but they didn’t answer.

Carter's mother, Cecelia Hill, cleans his face with a washcloth.

Carter was among the last children shot that day, a 24-hour stretch of gun violence that, according to police reports, left girls and boys from one coast to the other maimed or dead.

About 1:10 a.m., in Kansas City, Mo., 803 miles from Cleveland, Jedon Edmond found a gun in his parents’ apartment and pulled the trigger, accidentally firing a round into his face. Jedon, who died at a hospital, was 2.

Eighty minutes later, Damien Santoyo was standing on a porch in Chicago as a car drove by, and someone inside opened fire, striking the 14-year-old in the head. He died at the scene.

Less than two hours after that, at almost the exact same moment, a 15-year-old boy in Louisville was blasted in both legs outside a club, and a 16-year-old girl in Danville, Va., was fatally wounded on a street corner by a round meant for someone else.

Then, on a Metro car just outside the nation’s capital, an 18-year-old man accidentally shot his 14-year-old half brother in the stomach. Then, in Kansas City, Kan., three teenagers were shot inside a car, and two of them, one 16 and the other 17, were killed. Then, in a parking lot in High Point, N.C., a 14-year-old boy caught in crossfire was struck in the arm.

Hill allowed The Washington Post to tell his story and to interview him, his family, and his nurses and doctors because she wanted people to understand all that he endured.

What led to his shooting, she said, began earlier that night. She was leaving her mother’s apartment complex with Carter and Dahalia when they came upon the white Pontiac blocking the road. She honked and waited, until finally the car backed out of the way. It followed her onto the interstate. Then came the gunfire.

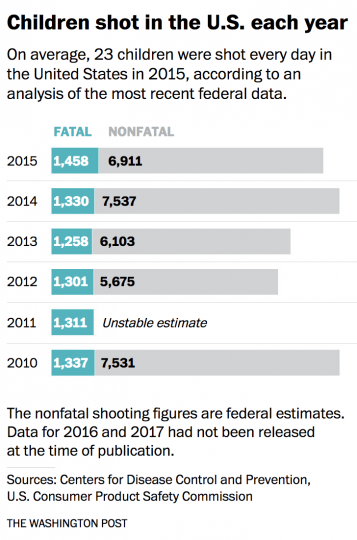

On average, 23 children were shot each day in the United States in 2015, according to a Post review of the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. That’s at least one bullet striking a growing body every 63 minutes.

In total, an estimated 8,400 children were hit, and more died — 1,458 — than in any year since at least 2010. That death toll exceeds the entire number of U.S. military fatalities in Afghanistan this decade.

Many incidents, though, never become public because they happen in small towns or the injuries aren’t deemed newsworthy or the triggers are pulled by teens committing suicide.

Caring for children wounded by gunfire comes with a substantial price tag. Ted Miller, an economist who has studied the topic for nearly 30 years, estimated that the medical and mental health costs for just the 2015 victims will exceed $290 million.

None of those figures feels abstract to Denise Dowd. The emergency room doctor at Children’s Mercy Hospital in Missouri has treated at least 500 pediatric gunshot victims in a four-decade medical career that began as a nurse in Detroit. She’s written extensively for the American Academy of Pediatrics and several national medical journals, both about how to prevent children from falling victim to gun violence and, when they do, how it affects them, emotionally and physically.

Dowd can rattle off number after number to illustrate the country’s crisis, but few are more jarring than a study of 2010 World Health Organization data published in the American Journal of Medicine last year: Among high-income nations, 91 percent of children younger than 15 who were killed by gunfire lived in the United States.

Like so many others who have pushed for gun-violence prevention, Dowd saw an opportunity in the aftermath of the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre, which left 20 students and six staff members dead.

She and her colleagues contacted close to two dozen schools and civic organizations in their Midwest community, offering to give presentations about how to protect kids from finding the weapons and harming themselves or someone else.

Then, just as lawmakers in Washington rejected efforts to expand background checks on people buying firearms and dozens of state legislatures continued to ignore pleas that they require guns to be safely locked away, Dowd got her first and only response, from a PTA group. Exactly three women showed up for her speech.

“People just don’t want to talk about it,” said Dowd, who wishes those people understood what bullets do to kids’ bodies.

How rounds react upon impact can be random and chaotic. Their size, direction and velocity, which routinely exceeds 1,500 mph, all affect the path of destruction within a child. Some bullets tumble inside the body after puncturing the skin, deflecting off bone before exiting at unpredictable angles that first-responders often struggle to quickly identify. Other bullets are designed to expand, creating a widening cavity as they shred through organs and arteries.

Dowd has seen the results in her young patients: lost fingers, toes, eyes and limbs, and mangled spleens, livers, kidneys, lungs and hearts.

What she has seldom seen, though, are children who live through rounds to the head.

Carter, his forehead scarred by a bullet, stands for a portrait.

When the pediatric trauma bay’s door slid open, Carter, at 3-foot-3, looked tiny atop the adult-size gurney, appearing smaller still as he was wheeled into the swarm of adults and bright lights and blinking machines towering over him.

Eyes panicked and neck braced with a miniature cervical collar, he screamed through the oxygen mask strapped to his mouth, but the nurses and doctors at UH Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital later said they took that as a good sign: His airway remained intact.

Still, his odds seemed grim. According to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, just 1 in 10 people who sustain a gunshot wound to the head survive it.

The emergency room staff checked Carter’s breathing and blood pressure. They sliced off his clothes with shears, then slid an IV into his left arm and strapped three stickers on his chest to monitor vital signs. Nearby, an orange-and-white cooler was packed with four liters of O-negative blood.

“One, two, three,” they counted up, then rolled him onto his side and scanned every inch of his body, looking for cuts or bumps or more punctures. They pressed on his spine to make sure it hadn’t been severed.

As the morphine began to take effect, he was hustled down the hall to a dim room with a CT scanner.

At 12:46 a.m., the images arrived on the cellphone of Efrem Cox, a 34-year-old neurosurgeon. The doctor’s pulse pounded, he recalled. The damage to Carter’s head was obvious. The bullet had struck the side of his skull, creating a nickel-sized crater in the bone before traveling 2.3 inches through the right frontal lobe and leaving an exit wound as big as a quarter. A fracture ran from one hole to the other.

Cox, who was at home, headed to his car. The boy, he knew, needed immediate surgery.

By then, Carter had returned to the trauma bay.

“Please, God,” his mother said, pacing next to him as his grandmother, Annette Hill, hurried inside.

They had worked so hard to prevent something like this from happening to him. Carter wasn’t allowed to play with toy firearms, and even when he pretended that his grandmother’s back-scratcher was a rifle, she scolded him. The family hated guns for a reason.

Efrem Cox, left, and Nicholas Bambakidis, Carter's neurosurgeons, talk in an operating room at UH Rainbow Babies -- Children's Hospital in Cleveland. The 3D images at top show the bullet's devastating damage to Carter's skull. The CT images below reveal the bullet's entry and exit wounds as well as a number of bone fragments. (Scan courtesy of Efrem Cox)

As a 7-year-old, Annette’s brother had been riding on the back of a bicycle when he was shot in the head. He had lived, but at 54, he still had a bullet in his brain and four decades of seizures in his past. Annette had never forgotten those times she’d wrapped cloth around a spoon and pressed it into her brother’s mouth so he wouldn’t bite off his tongue.

If her grandson survived, would that be his future, too?

“Gumma,” the boy murmured, using his nickname for her, so she walked over and sang him the “Barney” theme — “I love you, you love me” — as she had so many nights before.

“Boop,” Annette whispered at the end, gently bumping her finger against his ribs.

Now Operating Room 6 was prepped, and the neurosurgeons had arrived.

Carter was taken up the elevator to the second floor, where Cox saw him for the first time. Bits of brain, the doctor remembered, were visible along the side of the boy’s head, as blood and teardrops converged on his cheeks.

Carter’s eyes darted around the chilly operating room, searching masked faces for one that looked familiar. He found none. Terrified, he wet the blanket underneath him.

“It’s okay,” Cox told him, pausing to rub the boy’s arm.

The surgeon understood the stakes every time he worked on a child. He was still grieving for his own son, who had suffered from a devastating form of juvenile arthritis. The 2-year-old had died of respiratory failure in this hospital eight months earlier.

There was nothing the doctors could do.

“Put that aside,” Cox would tell himself before surgeries. He had treated at least 30 children struck by gunfire in his career, including a 17-year-old who had been shot clean through the back of his head on Cox’s first night as a neurosurgery intern in 2011. He had wrapped the fatal wound in dressing so the teenager’s mother wouldn’t see it. When the blood soaked through, the surgeon applied two more pads and wrapped it again.

“There’s nothing we can do,” he had told the distraught woman that night, but now, with Carter on the table in front of him, there was something he could do.

For so many reasons, that was remarkable.

If the bullet had been a higher caliber, it would have created a larger blast effect — like the ripple in a lake from the splash of a baseball vs. a marble — and ruptured blood vessels throughout his head. If it had struck a cerebral artery, he could have suffered a fatal hemorrhage before doctors ever saw him. If it had been designed to splinter on contact, his brain might have been pulverized. If it had pierced his left frontal lobe rather than his right, he may have been left unable to speak. If its trajectory had changed by just 30 degrees, it would have crossed over the brain’s midline and, likely, killed him.

Somehow, none of those things had happened. So, at 2:12 a.m., with Carter sedated and covered in blue drapes everywhere but on the front of his head, Cox pressed a scalpel into the apex of his small patient’s scalp. He needed to clean Carter’s wound to ward off infection, repair the cracked bone in the boy’s head and make sure there wasn’t more severe damage to his brain.

“It’s going to be okay, Mommy,” Carter’s sister, Dahalia, was saying in a room downstairs as she rubbed her mother’s back.

Across the top of the boy’s head, Cox said, he ran a foot-long incision from one ear to the other. The doctor peeled the skin down to just above the eyebrows and, with a drill, cut out a section of skull the size of a Zippo lighter. The surgeons washed out the opening and picked away four slivers of bone, none larger than half a Tic Tac.

With the bleeding and swelling under control, Cox slid the slab of skull back in place and screwed it secure with star-shaped titanium plates covering each hole.

By 3:05 a.m., Carter’s incision was sewn shut.

He would live.

In his white Spider-Man underwear, Carter sat cross-legged on the floor, bouncing a plastic toy horse across the hotel room’s brown carpet. For a moment, he didn’t think about the scary men who chased him or how cold it was in the place with the masked people or why he looked so different now than he used to.

On his left arm, where the nurses had stuck the needle he hated, was a Daffy Duck bandage, and over the horizontal slice on the center of his forehead, where the bullet had popped out, was a white strip of medical tape. The hair on the front half of his head that the surgeons clipped had begun to grow back. And there, at the crest of his scalp, was the surgical scar: a jagged, elevated ridge, shaped like an upside-down crescent moon and held together by a faintly visible coil of clear, dissolvable sutures.

Carter and his sister, Dahalia Bohles, a few weeks after the shooting.

Carter and his sister hadn’t asked many questions, but both vividly remembered what had happened that day, which began with a visit to their grandmother’s home.

He had stood on a neighbor’s shoulders and dunked a basketball in a hoop. Dahalia had climbed on the playground until she saw a spider near the slide. In the apartment, they ate pork and greens and watched an “Avengers” movie, and when it was time to go, they all loaded into Hill’s SUV.

Then, the kids and their mom got stuck in the road because of the white Pontiac.

Dahalia: “She was beeping her horn, and she was scooting up.”

Carter: “Mommy said, ‘Move.’ ”

Dahalia: “We got on the freeway, and that’s when they was following us.”

Carter: “They keep on getting up and getting up and getting up.”

Dahalia: “I looked over and saw a man pull up a gun.”

Carter: “It sounded like” — pausing, to raise his voice — “BOW, BOW, BOW.”

Dahalia: “They shoot the whole car up.”

Carter, on what the bullet felt like: “Hurt.”

Dahalia, on seeing her brother bleeding: “I was scared he was about to die.”

Carter, shrugging and slumping his head to one side, on why he was shot: “I don’t know.”

The boy already had woken up from his first nightmare, trembling. His doctors couldn’t predict whether he would suffer from seizures or developmental problems because of the injury, but his early progress had given them hope.

Hill was deeply thankful he had survived, but she so wanted to erase that night, to go back to the way things had been, before she’d talked to a social worker about finding the children counselors.

She saw glimpses of that old life, too, even in their cramped, temporary home.

“Can I play with her Barbies?” he’d started asking again about his sister.

Carter’s mother had tried to explain to him why, for now, he shouldn’t do front rolls on the carpet or attempt a handstand against the walls, but he mostly ignored her, and in a way that felt good because it felt normal.

When Dahalia pinned him to the bed and wouldn’t let him go unless he kissed her, Carter squirmed and laughed, but still refused.

Hill would soon buy her son a white wool cap to hide his scars. It made Carter, with those plum cheeks and brown eyes, look no different than he once did, at least on the outside.

That afternoon, as his mom sat on a bed scrolling through her phone, Carter, still only in his Spider-Man underwear, climbed up over the edge to join her. He picked up a remote and turned on the TV.

On CNN, two men in suits were talking about the violence in a place named Charlottesville. None of that made sense to Carter, so he changed the channel, to HLN and a show called “Forensic Files.”

The camera zoomed in on a black pistol, its barrel turned toward the TV.

Carter’s eyes widened, and his mouth slipped open. He stood on the bed, pointed at the screen and announced: “That’s the gun where I got shoot in my head.”

Steven Rich, Thomas Gibbons-Neff and Alice Crites contributed to this report.