Lives Lost

Through the stories of 60 ordinary people across 20 countries, “Lives Lost” captures the scale of the covid-19 crisis, the impact of each death on those left behind, and how trauma has been playing out across communities, countries, and cultures. The judges described "Lives Lost” as an “astonishingly powerful,” “multi-layered” package that “reveals the devastating, global-scale loss that the virus has had on humanity.” The judges also commended AP for its “tremendous institutional commitment” to a “beautiful project of human portraits despite the onslaught of daily news." Originally published by the Associated Press on September 30, 2020.

The coronavirus pandemic’s global toll is often talked about as a number - 2,000 dead. 15,000. 50,000. 100,000, and ever growing. Behind each one is a story, of a life well lived or cut short, of love, of perseverance, of heartache, of dancing, of laughter, of sacrifice, of bucket lists, of generosity.

Associated Press reporters around the world are working to capture these stories in a series called “Lives Lost.” Each is told individually, often with audio remembrances and photos from family members.

They are the stories of ordinary people who have sometimes done extraordinary things, or have had a profound impact on the loved ones they left behind or the communities they helped to build. When the pandemic is over, and life returns to normal, the biggest scar will be all the lives lost.

Here are just a few of them - a virtual scrapbook of a life:

Sudan-born doctor saw himself as ordinary Briton

At veterans' home, towering legacies of the dead

Woman of uncommon kindness, hoped for redemption

Generous Egyptian grandma was family 'jewel'

Families find solace in memories and mementos

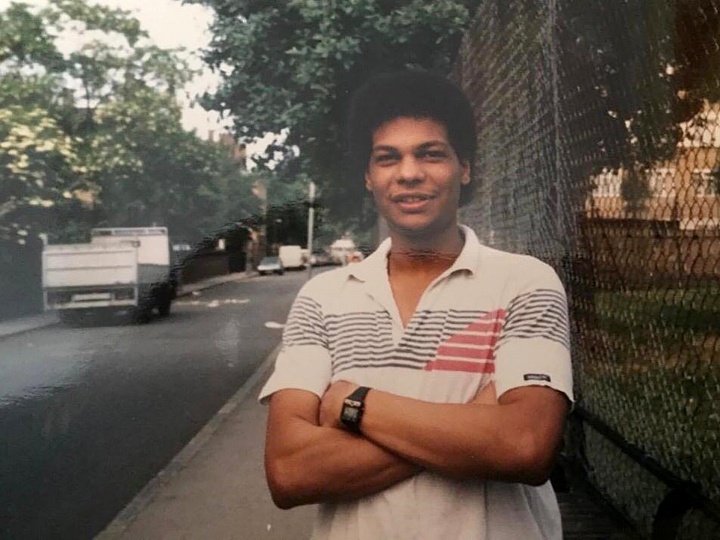

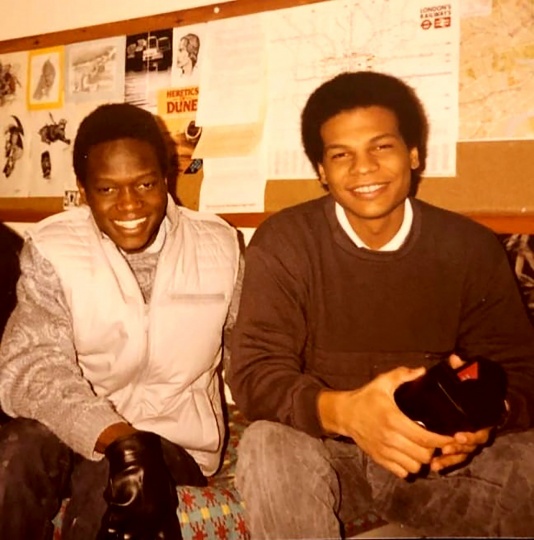

Sudan-born doctor saw himself as ordinary Briton

Sudan-born doctor saw himself as ordinary Briton

At veterans' home, towering legacies of the dead

At veterans' home, towering legacies of the dead

And, of service, in war or in peace, that often went unspoken when they returned home.

In their final years, these veterans found their place at the Holyoke Soldiers’ Home in Massachusetts. And in their final days, as the coronavirus engulfed the home and killed more than 70, they found battle again.

Left behind by these victims of the pandemic are those who were blessed by their kindnesses. Memorial Day dawns for the first time without them here, and a new emptiness pervades the little Cape Cods and prim colonials they once shared.

At these doorsteps, they were heroes not for valor, not for the enemies they defeated, but for the tenderness they showed. Peek through their bay windows and screen doors and bedroom panes. There is no blizzard of ticker tape, no gunfire of salute, just a void, a hole, a chasm of what’s been lost.

Seeking to capture moments of private mourning at a time of global isolation, Associated Press photographer David Goldman visited the homes of 12 families struggling to honor spouses, parents and siblings during a lockdown that has sidelined many funeral traditions.

Goldman used a projector to cast large images of the veterans onto the homes of their loved ones, who looked out from doors and windows. The resulting portraits show both the towering place each veteran held in their loved ones’ lives — and the sadness left behind. Here are their stories:

An image of veteran Alfred Healy is projected onto the home of his daughter, Eileen Driscoll, left, as she looks out the window with her sister, Patricia Creran.

Alfred Healy, 91, loved corny jokes and adored his family. He listened to audiobooks constantly and closely followed the news. He devoured history and was quick with facts on U.S. presidents. He was humble. He won a Bronze Star, but his family only found out how decorated a soldier he was when he was gone. He was a longtime U.S. Postal Service employee who rose to become a town postmaster. He was sharp as a tack and liked to deem things “snazzy” or “classy.” On his last night, the nurses gave him chocolate ice cream and showed him photos of some young relatives. And by dawn, he was gone.

An image of veteran Constance "Kandy" Pinard is projected onto the home she grew up in with her sister, Tammy Petrowicz, left, and brothers, Paul, center, and Brian Driscoll.

Constance Pinard, 73, had a life with struggles: A marriage gone sour, the pressures of raising two children on her own, family rifts that grew worse with an aggressive case of dementia. But there were so many joys, too: The miles she drove in her Jeep or flew in the air to reach new places as a travel nurse, the rank of captain she achieved, the thrill of meeting Barry Manilow, the musician she loved. Her sister Tammy Petrowicz remembers a woman overflowing with energy “like the Energizer Bunny,” who was 16 years older but “still could run circles around me.” The Air Force veteran loved meeting new people wherever she went. Petrowicz recalls standing in a grocery store line with her, chit-chatting with strangers like they were old friends. “She talked to anybody and everybody,” her sister says.

An image of veteran James Sullivan is projected onto the home of his son, Tom Sullivan, left, as he looks out a window with his brother, Joseph Sullivan

James Sullivan, 99, grew up with nothing and appreciated everything, a consummate gentleman who found joy in the small things — the Red Sox on TV, a cold Bud Light in his hand, a fresh tomato out of the garden. Sullivan was an artillery technician in the Army during World War II who won the Bronze Star. He had a mischievous side, as evidenced by the time his father told him he couldn’t play ball because he had to paint the garage. He obliged, painting it top to bottom, windowpanes and all. He was a liquor store clerk, a school custodian and a city councilman, a man who always beamed with a smile right up to the end of his life. He died four days shy of his 100th birthday. Quiet, unselfish, inquisitive about others. “How you doing, pal?” he’d ask. Whenever someone would ask him the same, he offered something similar: “Never had a bad day.”

An image of veteran Charles Lowell is projected onto the home he shared with his wife, Alice, for 30 years as she stands at left with her daughter Susan Kenney.

Charles Lowell, 78, was a missile guide technician and an IBM operations manager, a Masonic lodge master and town selectman, a volunteer firefighter and paramedic. Along the way, his life was littered with good deeds — the troubled teenager he’d take in, the hungry family he’d help with groceries — done with little notice or unmentioned altogether. “He didn’t tell people things like that,” his daughter Susan Kenney says. She remembers a father always teaching her something new and always trying to make people laugh, something his wife, Alice Lowell, says his colleagues appreciated. “It wasn’t like going to work,” she says of the man she knew since she was a child. “It was going to play with Chuck.”

An image of veteran Stephen Kulig is projected onto the home of his daughter, Elizabeth DeForest, as she looks out the window of a spare bedroom as her husband, Kevin, sits downstairs. After saying goodbye to her father for the last time in person, Elizabeth slept in the spare bedroom upstairs for two weeks as a precaution against possibly infecting her husband

Stephen Kulig, 92, always had a smile on his face and hard candies in his pocket. The list of roles he played was long: veteran of World War II and Korea, devoted Boston sports fan, bingo caller, school dance chaperone, altar server, soup kitchen volunteer, Knights of Columbus member. His daughter Elizabeth DeForest remembers a man who was a natural caregiver — for his wife of 63 years, for his five children and for his parents and in-laws. “I use the word fierce to describe him,” DeForest says. “He was really fiercely proud of his family. He was fierce in the way that he practiced faith and he taught it to our family and to all of us. Just fierce in the way he loved and protected the people that mattered to him.”

An image of veteran Chester LaPlante is projected onto the home of his son, Randy LaPlante, as he looks out a window with his wife, Nicole, and their sons, Evan and Blake, at their home.

Chester LaPlante, 78, had a knack for improving things wherever he went. He restored cars and could repair just about anything, and in the lives of his three children, he was the jack-of-all-trades father who knew how to make them smile. His son Randy LaPlante remembered his father giving him “bear rides” around the living room, rubbing his beard against his little face and buying him a go-kart. Later, the elder LaPlante took his son under his wing and taught him about being a machinist, a career he holds to this day. “I don’t know where I would be without him,” LaPlante says.

An image of veteran Harry Malandrinos is projected onto the home of his son, Paul Malandrinos, as he looks out a window with his wife Cheryl.

Harry Malandrinos, 89, was a quiet man, but had many stories to tell: of fighting a war in Korea, of touring the U.S. as a band’s drummer, of four decades as a public school teacher. “When he spoke, you listened, because he didn’t waste his words,” his daughter-in-law Cheryl Malandrinos says. He always had a joke, was a master woodworker, avidly rooted for the Patriots, Red Sox and Bruins and would happily settle for “Family Feud” if his teams weren’t on TV. Every now and again, his son Paul Malandrinos would run into a former student of his father’s who would sing his praises. “He was pretty much the working class guy that represents so many of us,” his daughter-in-law says.

An image of veteran Francis Foley is projected onto the home of his wife, Dale Foley, left, as she looks out a window with their daughter, Keri Rutherford.

Francis Foley, 84, never learned to read music but could play any song by ear. He loved a cup of coffee and something sweet from Dunkin’ Donuts. He kept the nurses at the home laughing. He was fiercely protective of his family. Ask his family about the man they lost, and the words flow easily about the card-carrying union carpenter, Army veteran, devoted husband of 54 years and father of four. “He was strong. He was funny. He was engaging. He was ornery. He was feisty,” his daughter Keri Rutherford says. “He was still full of life. And then within days, he’s gone.”

An image of veteran Roy Benson is projected onto the home of his daughter, Robin Benson Wilson, left, as she looks out a doorway with her husband, Donald. An image of veteran Emilio DiPalma is projected onto the home of his daughter, Emily Aho as she looks out a window with her husband, George. An image of veteran James Mandeville is projected onto the home of his daughter, Laurie Mandeville Beaudette, as she looks out a window with her son, Kyle, left, and husband, Mike.

Roy Benson, 88, whistled a lilting song throughout his life, one of the things imprinted on the minds of those who loved him, like the way he’d stir sugar into his morning coffee or holler for a visitor to return the minute they stepped out the door. His daughter Robin Benson Wilson calls them “comfort sounds” that signaled “the world is good.” He was a towering 6-foot-4. He made friends easily and often, always finding a familiar face wherever he went. He was a mechanic in the Korean War and it seemed like he could fix anything. With old age, his ability to whistle faded. But during a Christmastime visit by Benson Wilson to the Soldiers’ Home, her father managed to pucker his lips and offer a bit of that familiar tune one last time.

Emilio DiPalma, 93, had gone off to war as a happy-go-lucky kid, but it didn’t take long for his Hollywood visions of battle to dissolve into the reality of watching friends die. After the Germans were defeated, DiPalma was sent to Nuremberg, where he made copies of documents detailing war crimes, watched over Nazis in their prison cells and stood guard beside the witness box in the courtroom where the evils of genocide were detailed. One time, he filled the glass of one of the most powerful Nazis — Hermann Goring — with toilet water. Back home in the U.S., he lived a life of humility, rarely talking about his service. “He did all of this in World War II and we hardly knew about it,” says his daughter Emily Aho.

James Mandeville, 83, had a playfulness to him that never seemed to fade. With his grandchildren, he’d swim and wrestle and play basketball, even after he started using a wheelchair. He’d play cards with his daughter Laurie Mandeville Beaudette and, if she left the table, she’d return to find the deck had been stacked. She took to calling him “Cheater Beater.” He found joy in babies and dogs and for all his fun-lovingness, he imparted something deep in those who were close to him. “He always made me feel like I was the most important person in the world,” she says. “We were best friends.”

An image of veteran Samuel Melendez is projected onto the home of his nieces, Janet Ramirez, right, and Mary Perez, as they look out a doorway.

Samuel Melendez, 86, would clam up and appear sad when someone would ask about his time in Korea. But he was affectionate and easygoing, a man who’d let a young relative have a seat on his lap or give them a dollar from his pocket, which made them feel rich. He loved the island of his heritage, Puerto Rico. He loved dominoes and family gatherings and would jump on a plane whenever someone needed him. When he became less independent, he went to live with his niece Janet Ramirez and when he needed more help, he moved to the Soldiers’ Home, where she is a nurse’s aide. She lost her own father when she was young and as her uncle grew sicker, Ramirez slipped away to his room to hold his hand or to play Spanish music on her phone and put it to his hear. “I felt like he was my dad,” she says.

Woman of uncommon kindness, hoped for redemption

Woman of uncommon kindness, hoped for redemption

By MATT SEDENSKY

October 16, 2020

This 2017 photo provided by Tressa Clements shows her daughter, Saferia Johnson, at the home of a cousin in McDonough, Ga. Johnson earned a reputation as a mentor and mother figure to many and time and again, she was a fast friend, who followed a chance encounter with an outflow of kindness that ensured would-be strangers instead lived lives forever intertwined. In August 2020, she died at the age of 36 from COVID-19.

And time and again, Saferia Johnson was the fast friend, who followed a chance encounter with an outflow of kindness that ensured would-be strangers instead lived lives forever intertwined.

There was a confounding story that would be told about Johnson that ultimately would upend her life, but those who knew her have others they want heard: Of a Georgia woman so generous, of an old soul wise beyond her years, of someone whose goodness seemed to have no limits.

Tywanna Floyd met Johnson at training for a customer service job and before long, Johnson was so key in the life of her new friend’s 3-year-old daughter, she was like a second mom.

“That smile,” she says in awe, trailing off as she hints at the magnetism of her friend.

James Moye was adjusting to life as a single father, sitting in a stairwell at his apartment building, trying to braid his daughter’s hair when Johnson happened to pass by. She took over the girl’s hair and soon was watching her on weekends, helping her with schoolwork and signing her up for gymnastics.

“You don’t find genuine love like that,” he says.

Nikki Brown met her in their college dorm and by the time she fretted about being pregnant a few years later, there was no one besides Johnson she’d want accompanying her to the doctor. After the child arrived, she was the ever-present godmother, showering the baby in gifts.

“The smartest girl I’ve ever known,” she says. “The sweetest soul.”

And so it repeated: Glowing words of the Thomasville, Georgia, native as a churchgoing, mild-mannered woman who had been a motherly figure to so many and who now doted on two of her own.

Until the U.S. government had words of its own.

The indictment came just before Christmas four years ago. Prosecutors claimed Johnson, her boyfriend and another man ran a fraud scheme, filing fake tax returns and collecting the refunds.

All told, the government would eventually claim, it was scammed of nearly $1.5 million, with almost $500,000 going to accounts in the names of the three defendants.

Johnson told few what she was accused of and to those she did, it seemed puzzling.

Her mother, Tressa Clements, wondered how it could be true, when she was helping pay her daughter’s bills and she had to rely on a public defender because there was no money for another attorney. Floyd thought of her friend’s beat-up car, of the modest home she rented, how she never spent lavishly on clothes or wore a ring on fingers she complained were too chubby.

“It just didn’t make sense,” Floyd said.

Johnson didn’t absolve herself completely from the charges, her friends and family say, but maintained she wasn’t guilty of everything. More than anything, she felt she’d been conned by the father of her children. For their sake, she saw one path forward.

This 2011 photo provided by Tressa Clements shows her and her daughter, Saferia Johnson, left, during celebrations for Saferia's masters degree from Valdosta State University in Georgia.

She entered a plea agreement that brought a 70-month sentence. A woman whose mother called her Rabbit and who neighborhood children knew as Ferry now would be known as Inmate #00313-120.

When she arrived at prison in Marianna, Florida, one other new inmate awaited processing and Johnson again made a new friend. Scarlett King remembers the anxiety that day, how Johnson introduced herself and conversation bloomed.

King, too, had never been in trouble before getting caught up in a fraud scheme with her boyfriend. She spoke of a daughter she’d just dropped off at college; Johnson told her of two young sons she left behind. Johnson talked of her work with juveniles in the justice system. They both expressed fear about what came next.

Johnson grabbed her hand and held it: “We’re going to be fine,” she said. “It’s going to be OK.”

When the process was over, the two learned they were bunkmates and, through subsequent transfers that brought the women to two other prisons, they remained close friends.

Johnson prayed at Sunday services and showed up to Bible studies and prayer sessions and worked prison jobs as an orderly and in the laundry and in a warehouse driving a forklift.

She stayed in touch with those she mentored and found ways to make sure they felt her love, even enlisting another inmate to knit baby clothes she sent to an expectant mother. She helped tutor some inmates pursuing high school diplomas and scurried to help others when they needed a hand carrying a heavy load from the commissary.

Johnson even came to peace with the man she blamed for her incarceration, writing a letter to the father of her children that King said expressed forgiveness for what had happened.

This 2009 photo provided by Tressa Clements shows her daughter, Saferia Johnson, with her grandfather, Lindsey Johnson Sr., during celebrations for Saferia's graduation from Valdosta State University in Georgia.

On August 2, her mother stood outside the window of her ICU unit. A nurse took pity on her, sneaking a cell phone in a surgical glove inside so she could speak to her only child. She told her Rabbit she loved her. She prayed to God she’d be healed.

By morning, Johnson was dead at 36. When the news reached King, she fell to her knees. Clements went home to her two grandsons, 5-year-old Kyrei and 7-year-old Josiah, and told them their mother caught the virus and was going away to be with the Lord. At the funeral, Moye brought his two daughters to the gravesite and they stayed late, sobbing.

All of them think of what might have been for this woman who dreamed of her release, of earning a doctorate, of rebuilding what was broken and, more than anything, returning to her boys to be the mom they deserved.

“Her life was gonna be beautiful,” Clements says.

Generous Egyptian grandma was family 'jewel'

Generous Egyptian grandma was family 'jewel'

Dr. Sherif Waheed poses.

By SAMY MAGDY

May 6, 2020

BAHTIM, Egypt (AP) — Gold and silver streamers fluttered in the breeze, hung from house to house down the alley, a festive sign of the holy month of Ramadan.

Usually, Ghaliya Abdel-Wahab would be giving out food to her neighbors for the holiday — big platters of stuffed cabbage leaves or cakes or buttermilk flatbreads. There wasn’t a family on the street who hadn’t enjoyed her food.

But the alley in Bahtim, just outside Cairo, was silent. Abdel-Wahab, 73, and two of her sons were dead. The novel coronavirus struck her family, infecting 45 relatives. It forced the lockdown of some 2,000 neighbors to their homes for weeks.

The street where 73-year-old Ghaliya Abdel-Wahab died from COVID-19 on April 6, 2020, one of two streets on complete lockdown in Bahtim, Shubra el-Kheima neighborhood, Qalyoubiya governorate, Egypt. April 17, 2020.

Fear of the virus left the beloved grandmother’s relatives scrambling to find a way to bury her — after some in the district she’d lived in all her adult life barred her body from the local cemetery.

“All my memories with her were sweet ... She was always helping us, always looking after the whole street’s people as her children,” said one of her neighbors, Umm Gouda, fighting back her tears.

Umm Gouda was Abdel-Wahab’s best friend for 40 years, ever since Umm Gouda moved in across the alley. From the start, Abdel-Wahab opened her home, letting Umm Gouda’s kids come other to take baths as her friend finished building her house.

For the next four decades, they lived together across a street so narrow one of them could practically lean out her window and arrange the other’s laundry dangling on the line. They watched each other’s children grow up. They cooked and shopped at the nearby street market together.

The daughter of a farming family in the Nile Delta, Abdel-Wahab came to Bahtim in the 1960s with her husband not long after they married. The government was turning the area — a stretch of small towns amid green fields and canals from the Nile just north of Cairo — into an industrial hub. The young couple were among the rural villagers who flowed in to work in the new state-run fabric, metal and ceramics factories.

Umm Gouda, a close friend of 73-year-old Ghaliya Abdel-Wahab.

Her husband found a job as a worker at Industrial Projects and Engineering, a government steel conglomerate. Abdel-Wahab raised chickens at home as a second income. They had eight children — four sons, most of whom also found jobs in the nearby factories, and four daughters who were married off and soon had families of their own.

Over the decades, the factories declined, neglected as the state moved from socialism to privatization. The area became poorer, and more migrants from the impoverished countryside flooded in. Abdel-Wahab found her district transformed into a decrepit sprawl of densely populated, illegally built concrete towers stretching for miles, the sewage systems decaying, the canals paved over or choked with garbage.

The grandmother’s generosity always shined through. When the husband of another neighbor, Zeinab Ismail, was sent to prison a while back, Abdel-Wahab stepped in to help, giving her money to pay school fees for her daughters.

“She helped without being asked,” Ismail said. “Hajja Ghaliya did everything, gave me money, food and anything I needed.”

Her husband died in 2018, but Abdel-Wahab had her family close by — her sons and their families all lived in the same building with her. One of her grandchildren, Sayed Naser, called her “the jewel of the family.”

“My grandma was very kind, unbelievable kindness with all people, relatives or non-relatives,” he said.

The virus first hit her son, Abdel-Raouf, in March. At the hospital, the doctor said his fever was just a common flu and sent him home. Within days, he’d worsened and was rushed to a fever hospital.

But it was too late. The virus was racing through the family.

A man looks at one of two streets closed off by security forces after 73-year-old Ghaliya Abdel-Wahab died from COVID-19 on April 6, 2020.

Ghaliya Abdel-Wahab poses for a photograph with her grandson. The novel coronavirus struck her family with horrific speed, infecting 45 of her relatives.

When health workers and two of her grandchildren took her for burial, they found a group of Bahtim residents blocking the entrance to the cemetery.

“They were waiting for us,” Naser said. “They said, ‘You will not bury anyone here. Do you want to get us sick?’”

They took her to her ancestral village, Kafr Kala al-Bab, in the Delta. There, too, residents initially tried to block the burial. Her body waited in the ambulance for more than 15 hours as police got involved and finally allowed her to be buried.

The next day, her son Abdel-Fattah died, followed later by her eldest son, 54-year-old Hisham. They were buried in unmarked graves in a charity cemetery. At least 45 family members were infected. Naser’s 21-year-old sister, Yasmine, was pregnant with her first child when she was infected and gave birth in quarantine. They named the boy Yamen — and nicknamed him “Corona.”

“Our family is in war with the coronavirus,” said Naser. “This is a test, a test from God.”

Back in Abdel-Wahab’s alley, the thought stung that someone blocked the burial of the woman they all knew for her generosity. Once the family is out of quarantine and isolation, the neighbors want to do right by them and give their grandmother the farewell she deserved, said one neighbor, Sally Ahmed.

“We will hold a funeral service and receive them in the best way,” she said.

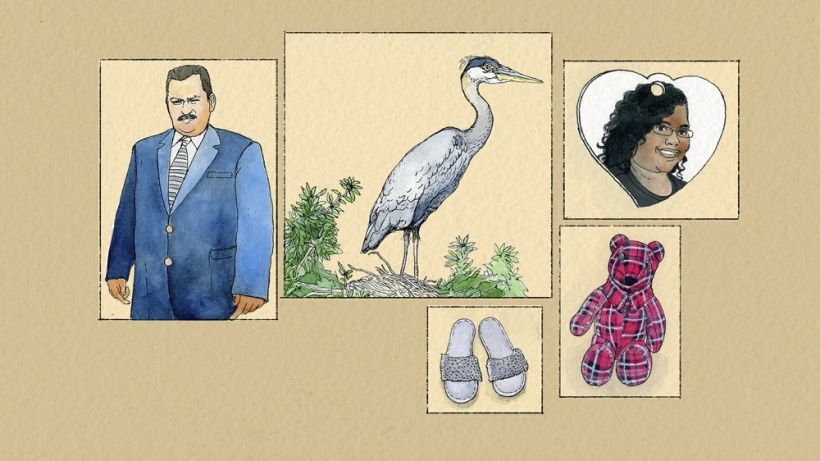

Families find solace in memories and mementos

Families find solace in memories and mementos

By PETER PRENGAMAN and RAGHURAM VADAREVU, with illustrations by PETER HAMLIN

December 30, 2020

Long after the funeral or memorial, if one was even possible, and long after the condolence cards, the phone calls of support, there is simply the emptiness. That’s when the memories rush in.

They can come from the feel of wearing a loved one’s necklace, its closeness trying to bridge an impossible distance. Or the embrace of the teddy bear made from their old flannel shirts, familiar and safe. Or the sight of a heron, a symbol of a family’s heritage, regal and proud.

The search for solace takes many forms. But when a global tragedy, a pandemic, disrupts that most delicate of life’s moments — a loved one’s passing — finding comfort also takes on new importance. A single life can become lost among many, seemingly blending into an ever-growing death toll.

Over the last year, Associated Press journalists profiled dozens of ordinary people around the world who died from the coronavirus, aiming to tell the story of COVID-19, one person at a time. As the turbulent year comes to a close, the AP revisited the families and friends of 10 of those lost to see how they are coping.

In their stories, windows into private grief amid a public calamity, they are finding comfort in the act of remembering, whether it’s in the cradling of an item their loved one left behind, in a vow to fulfill a promise they would’ve blessed — or in imagining them, their strength, in better days.

An illustration made from a photo of Yurancy Castillo's sandals provided by Mery Arroyo.

The gray sandals Yurancy Castillo left in her family’s home in Venezuela sit next to her bed with a Tweety bird pillowcase.

Keeping the shoes there allows her mother to briefly trick herself into thinking that her spunky curly-haired daughter will return soon. But now, six months after her death at 30 from COVID-19, that grows harder to do.

“Life isn’t the same for me,” Mery Arroyo says. “Every hour, I’m thinking of my girl.”

Castillo fled Venezuela three years ago as her country’s economic and political turmoil worsened and her family’s fridge grew empty. By bus, she traveled across four countries to Peru.

It wasn’t long before she found odd jobs like selling sewing machines and waitressing – work that offered a measly salary, but enough to send money back home, so that her parents could buy food. She’d call her mother, telling her she dreamed of home.

Then, the virus took her life. Now, her ashes sit in a Lima apartment, where her sister is watching over them until she can return them home.

In Venezuela, Arroyo’s home is filled with reminders of her daughter. Photos of her smiling fill tables and walls.

And then there are the sandals, worn and faded. Arroyo imagines her daughter left them behind because they were too tattered to take on the journey to a new life. At first, they were a reminder that her absence was only temporary.

Sometimes, for a brief moment, Arroyo can convince herself that’s still true.

— Christine Armario

An illustration made from a photo of a pendant with Saferia Johnson's portrait provided by Tressa Clements.

Saferia Johnson’s favorite chair, a rocker with a blue cushion, is empty. Clothes that she excitedly bought hang with tags, unworn. And the smile of the Thomasville, Georgia, native, so beaming and inviting, now lives on only in a heart-shaped photograph on a necklace her mother wears.

Tressa Clements has found herself continuing to talk to her since her daughter died from COVID-19 in August and hearing her voice echo in her mind. Sometimes it’s the mundane, like the Christmas lists of Johnson’s two sons, 5 and 7. Other times it’s the void that sends Clements into tears.

“She tells me, ‘Mom, stop crying,’” Clements says. “She tells me how beautiful it is where she is.”

The pain of the 36-year-old’s death is complicated for those she left behind by the absence that preceded it. Johnson had been serving a prison sentence in Florida on fraud charges and, though visits and calls and messages kept her connected, normalcy had already been upended.

Johnson’s loved ones are now trying to find their footing in a world that’s familiar and different.

Her aunt still makes macaroni and cheese, but it comes out of the oven without its most enthusiastic fan waiting. Johnson’s little boys are as inquisitive as ever, but now they’re asking if mommy might still be here if she only had a mask to protect her.

Holidays still come, but Clements was too sad to get out of bed on Thanksgiving and she wondered if a Christmas tree was right, too.

When Clements sees her grandsons upset, she shakes herself to cheer the boys. That’s what convinced her to put the tree up, complete with the ornaments Johnson made as a child – little bells she decorated, and a paper heart with a picture of her in the center from second grade.

“Mommy would want you to be so happy during Christmas,” she says she told the boys.

— Matt Sedensky

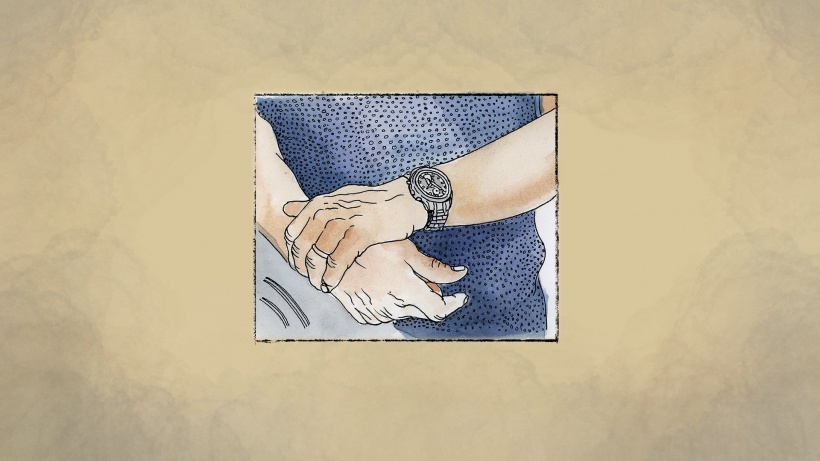

An illustration made from a photo of Amged El-Hawrani's hands provided by his family.

Dr. Amged El-Hawrani’s family remembers his hands.

His wife, Pamela, thinks about every scar, every shape, every millimeter of the hands that made her feel safe, protected and loved. His brother Amal recalls their strength — a reflection of the confidence that helped Amged become a respected ear, nose and throat specialist in England.

“You know, surgeons are supposed to have long, delicate fingers,” Amal says. “But his hands were made for boxing or something.”

When Amged, 55, died from COVID-19 on March 28, he was one of the first doctors in Britain to succumb to the virus, becoming a symbol of the danger faced every day by healthcare workers battling the virus.

His family recall simpler things, like his passion for cars. His son, Ashraf, remembers his father behind the wheel, talking about World War II and introducing him to the music of Bob Marley and Jimi Hendrix.

There were deeper lessons as well. “He taught me the significance of respect and equality,” Ashraf wrote in a memorial honoring his father. “He also stressed the importance of not worrying about the things I cannot control, which he displayed to me right up until the end of his life.’’

That philosophy was forged early. Born in Sudan, Amged grew up in western England, where he and his brothers were often the only non-white children in the neighborhood. But he loved his new home, committed himself to medicine and never let anyone else’s opinion bother him.

He persevered. And now, so does his family.

“Life just takes you forward,” Amal says. “Regardless of whether you are ready or not.’’

— Danica Kirka

An illustration of a heron.

Amid profound heartache, Marc Papaj is looking to his roots for solace.

A member of the Seneca Nation’s Heron Clan, Papaj and his family have long drawn pride from the graceful bird. Since his mother, grandmother and aunt died of COVID-19 in late May and mid-June, he’s been drawing strength from images of herons.

“Friends and family have been sending drawings of three herons together,” says Papaj, while recently cleaning out his mother’s house in Salamanca, New York, on the Allegany Reservation. “Our tribe is matrilineal, so to lose three prominent members who were mothers is such a blow.”

Papaj’s grandmother, Norma Kennedy, and his mother, Diane Kennedy, both had long careers with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, taking on various roles that ranged from distributing funds to native communities to being a peacemaker judge on a tribal court. Papaj’s aunt, Cindy Mohr, was a long-time elementary school teacher.

Normally during the holidays, there are negotiations about where the celebrations will take place: Papaj’s home, his mom’s home or the homes of his grandmother or aunt. Before the pandemic changed everything, they all lived within an hour’s drive of each other in western New York state.

“It was always a great holiday no matter what,” says Papaj.

This year, there is just silence.

“I tend to well up first, get that tickle in my throat,” says Papaj, recounting how his wife, two teenage daughters and 10-year-old son took time at Thanksgiving at home to remember who wasn’t with them. “It speaks volumes because this would have been the Thanksgiving to lean on family.”

— Peter Prengaman

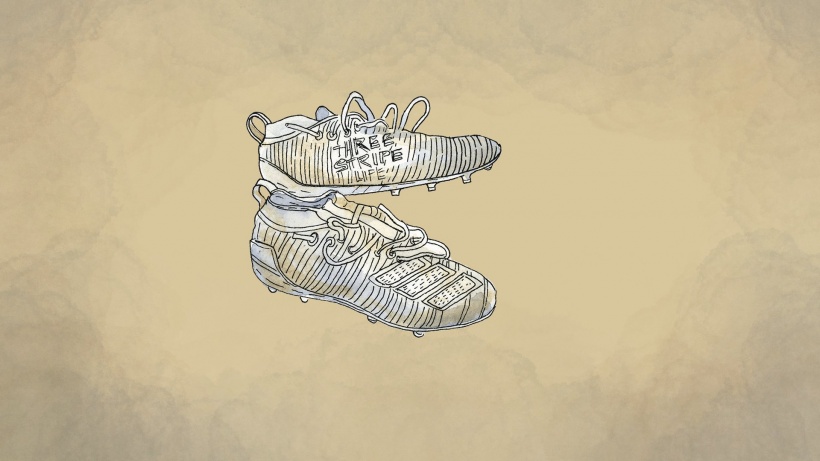

An illustration made from a photo provided by Raymond Millare of football cleats given to him by Willie Talamoa.

Since Raymond Millare’s football coach died from the coronavirus, there have been times when the Hawaii teen would sink into his own world.

Millare would throw on cordless headphones to listen to melancholy music and scroll through old photos with Willie Talamoa on his phone. Some afternoons, he would think back to how Talamoa would swing by his house to pick him up for practice.

“Honestly it’s like it’s not even real. But it’s reality. So I kind of just got to hang in there and stay strong for him, like he would do for me,” the 18-year-old high school senior says.

Talamoa died at 36 in August. Fellow coaches and players in the Honolulu neighborhood of Kalihi where he grew up remember him as a mentor and father figure who generously gave his time and money to provide young people opportunities he didn’t have.

Millare was one of them, and he’s felt his absence. Sadness has at times made it hard for Millare to control his feelings and focus in school. But his parents remind him that Talamoa is still with him, even if the coach is no longer present physically.

“That kind of motivates me and makes me want to be active again,” he says, adding he wants to finish the school year strong for coach.

The coronavirus pandemic prevents Millare and his teammates from holding group practice or playing. So Millare works out at home or a park. He likes to put on the pair of cleats Talamoa gave him because it makes him feel like he’s warming up for a game or going to practice.

And, most of all, he likes them because they remind him of “Coach Willie.”

— Audrey McAvoy

An illustration made of pendant belonging to Priya Khanna from a photo provided by her family.

Anisha Khanna isn’t sure when her older sister Priya got the necklace, but it was clear she loved it — a pendant, with her initials, “PK,” inside, a flower and a symbol of an eye meant to ward off bad luck.

Now, it is among Khanna’s most cherished possessions, a reminder of her sister, a fellow physician in New Jersey, who she admired for her kindness and intelligence and who she lost to COVID-19 in April.

“It was something small, but I know she liked it a lot and that meant the world to me,” she says.

Dr. Priya Khanna died at 43 just days ahead of their father, Dr. Satyender Khanna, 77, who also succumbed to the virus. They both died in the same northern New Jersey hospital.

The ensuing months have compounded the pain, with the family’s Hindu burial traditions being upended by the pandemic restrictions and their mother, Dr. Kamlesh Khanna, overcoming the virus and then getting shingles.

“Every day is a struggle, a lot of ups and downs,” said Anisha Khanna, the youngest of three sisters who followed their surgeon father and pediatrician mother into medicine.

The family has found comfort in the company of others, both in person and virtually.

On Priya’s birthday in November, Anisha and several of her sister’s friends met at a restaurant, a rare outing during the pandemic, and ate some of Priya’s favorite dishes. Kamlesh Khanna joined a Facebook group of COVID-19 survivors, some of whom seek out her medical advice.

“It makes her feel like she’s not the only one,” Anisha says.

— Dave Porter

An illustration made from a photo of Hannelore Cruz's piano provided by grandson José Miguel Cruz da Costa.

José Miguel Cruz da Costa has been busy. Since his grandmother Hannelore Cruz passed away from COVID-19 in March, he has been refurbishing the house she left behind in Portugal — and adding a very personal touch.

In a “special corner” of the living room, he’s placed her black upright piano, beneath a painting of an orchestra made by one of her uncles in Austria. It’s a tribute to the “angelic voice,” as he calls her, with a passion for classical music.

“I’m sure she’d approve,” he says.

Cruz, who died at 76, arrived in Portugal as a child evacuee from devastated Vienna after World War II. She eventually pursued a singing career in the northern Portuguese city of Braga, taught singing and performed at local weddings and church recitals.

A flamboyant dresser, she’d turn heads on the streets of conservative northern Portugal.

Her grandson visited her almost every day after she moved into a care home for the elderly. He has lost, he says, a “cherished” routine — joining her for coffee after breakfast and, on Fridays, taking her to the hairdressers and then out for lunch.

The Christmas holiday laid bare another absence: her homemade pumpkin muffins and other traditional desserts of northern Portugal.

Her grandson says the family misses their “kitchen virtuoso.”

— Barry Hatton

An illustration made from a photo of Tomas Lopez's taco truck.

The big green taco truck’s engine started to rattle, and Isaac Lopez thought of his late dad.

“I wish I could talk to him to ask him about it,” he says. “I’ll probably have to get a mechanic. He would have fixed it himself.”

Tomas Lopez died at 44 from COVID-19 in April. The jovial face of the family’s Taco El Tajin restaurant and food trucks in Seattle, he had long served Amazon employees, construction workers and other customers with a hearty “Hello, my friend!”

Isaac, 19, has taken over many of his father’s roles in the business.

“I didn’t know what to do with my life,” Isaac says. “Now I do, and I love it.”

Still, it’s hard work, especially without his dad’s companionship and guidance.

Isaac used to sleep until 7 a.m. before his shift in one of the trucks. Now he’s up with his mom by 4, making sure there’s gas and propane for the trucks, getting supplies at the store and preparing food at the restaurant before driving one of the trucks to Seattle.

More than anything else, Isaac says, the taco truck his dad always drove — the biggest one — reminds him of the old man.

He doesn’t usually drive that one, though. It’s too big, too scary to handle. He drives a smaller one to the same neighborhood his father served for years, dishing up burritos, tortas and flan to many of the same customers.

As they approach the truck, those customers hear a familiar greeting: “Hello, my friend!”

— Gene Johnson

An illustration made from a photo provided by Tri Novia Septiani of Michael Robert Marampe's keyboard.

When Tri Novia Septiani sometimes visits the Jakarta apartment of Michael Robert Marampe, her fiancée who died from coronavirus, the memories are so overwhelming that she has had to put away things that remind her of him — a teddy bear, books and some of his clothes.

“I cannot stand to see them around,” she says.

There are several items that she won’t put away: an electronic keyboard, a piano and several guitars he used to compose the song, “You Are The Last One,” for her. It was to be sung at their wedding in April, the same month he died at 28 of COVID-19 in Indonesia.

Music brought the couple together. Septiani, a fashion designer and singer, met him at the church where he played piano. They formed the duo, Miknov, covering popular songs and composing their own music they uploaded to Instagram and YouTube.

Over the last several months, Septiani has been working with musicians to produce the song. She sings the solo, just as they planned, but without the man she was to make a life with.

“It is very difficult to sing that song with a different pianist,” she says. It took her a very long time to finish the song because the recording sessions frequently ended with her in tears.

“I have accepted that he is gone,” she says. “But I do not want to say goodbye.”

Still, producing the song was a way to honor his love for music. When she sees his keyboard and piano, she is reminded that she will go on with her memories of him and the spirit he showed in the passions he pursued.

— Edna Tarigan

An illustration made from a photo provided by Meghan Carrier of a teddy bear she made from her father Cleon Boyd's flannel shirts.

Meghan Carrier remembers how her dad, Cleon Boyd, loved his flannel shirts, how he’d wear them during ski season and how he couldn’t be talked out of them — even when the weather in Vermont warmed up.

Carrier has turned to her dad’s flannels collection lately as she wrestles with the sadness of losing him and his twin brother Leon to COVID-19.

She’s knitted a teddy bear out of her dad’s oversized flannel shirts, and included a collar from one of them. She can still smell her dad’s favorite cologne, Jovan Musk, on them. She sometimes pulls the bear out and gives it a hug.

“It just makes me feel closer to my dad. It still smells like him,” she says. “It gives me a little bit of comfort.”

The twins died a week apart in April, leaving a hole in everything from birthdays to musical jam sessions that are so important to the Boyd family. Another of Cleon Boyd’s children, Chris, says he can’t take listening to his dad’s favorite country songs.

“I don’t play my guitar as much as I should. Songs on the radio, I have to shut them off,” he says. “It makes me cry. I can’t do it.”

Relatives haven’t been able to have a traditional funeral for them, settling instead to spread their ashes around favorite haunts: the sugar shack where the brothers held court during maple syrup season; Haystack Mountain; and the summit of Mount Snow.

“It was the one spot my dad absolutely loved,” Carrier said of Mount Snow, where he groomed the ski trails for years. “To be able to watch the sun come up and feel the sun touch your face, it warms you up, and reminds me of my dad.”

— Michael Casey

This story is part of a yearlong series, “Lives Lost,” which tells the stories of ordinary people from across the world who died from the coronavirus and the impact they had on their loved ones and their communities.