Family on the Front Lines

Being a mother with five children and a war-reporter husband means early lessons in violent conflict, world politics and the perils of freelance journalism.

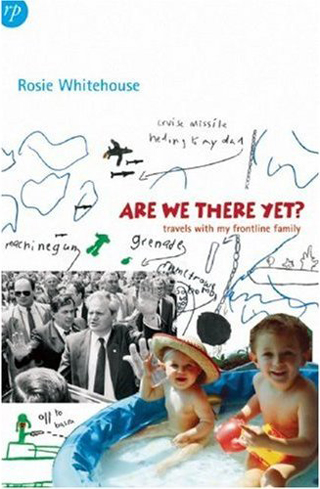

This article is an excerpt from Rosie Whitehouse's book "Are We There Yet? Travels with My Frontline Family." This excerpt is also available in Serbian/Croatian/Bosnian on the Dart Centre Western Balkan Network page.

It’s a snowy day in Sarajevo. My husband Tim Judah and I are taking the younger of our five children sightseeing. The builders are busy painting and papering over the cracks. Almost fifteen years on the war is sliding into the history books. We’ve driven up onto the hills above the city. Down below us in the valley is the Holiday Inn.

Tim pulls over and we all get out. “You know, this is the first time I have ever got out of the car here,” he says, as he explains to the kids that this is one of the spots from where the Bosnian Serbs shelled the city. He points up the road to Pale. “I’d come down here in the car at about hundred miles an hour. If you can see them, they can see you. This place was a deathtrap.” I stare at the icy, empty road. “The weather was usually worse than this.” He adds. “Cor!” says nine-year-old Jacob, wide eyed. I can see our red family saloon car shoot past. It haunts me for days.

I am glad I am somewhere that I’m not the only person to have the occasional flashback. When we lived in Belgrade during the wars in Croatia and Bosnia, I never felt that I was a freak worrying about what my husband was doing on a frontline. Then we moved back to London in 1995 where people can turn off their TV sets and forget all about something unpleasant happening far away.

My isolation reached its zenith during the invasion of Iraq in 2003. One sunny spring morning I went to the supermarket. I was busy stuffing a packet of frozen peas into a carrier bag when I noticed that at the checkout was a widescreen TV showing a live feed from the battlefield. A journalist was sprinting across the road after some soldiers. Fortunately, Tim was in Baghdad and this report was from Basra but what hit me was that it had probably never entered anybody's head in the supermarket, at the BBC or among the chattering classes, who were conducting a heated debate in the newspapers about the way the war was reported, to even consider what effect this wall-to-wall TV coverage might have on the families of journalists reporting the conflict.

It is not just when something goes terribly wrong, and your husband is murdered or kidnapped, that journalism infringes on family life. Tim was away in Baghdad for three months. I had to explain that absence to the kids. No he does not love Iraqis more than you; it is just that someone has to be there to tell the world what is going on. On top of it, I was a broke single mum. As a freelance he had had to put up most of the thousands of pounds of expenses himself. I was left with a massive overdraft, and there were only baked beans and supper savers bread for supper. Not much to boost morale in that.

My five children had known the war was coming for months. We discuss their father's job openly. They have grown up with war. This I think has been tremendously important. We have been able to back up Tim through what have been some very difficult assignments, precisely because they know exactly what he has been doing.

Not that it is all gloom and doom in our house. Sometimes it is wildly exciting, and following him around the world has given them incredible opportunities, but they are aware of the dangers. It’s made them wiser and more considerate but often isolated them from their contemporaries.

Yet, in 17 years, only once has someone from a newspaper called me to see how we are doing. Occasionally, when Tim is off at a frontline, some cheerful subeditor will call up, with the voice he uses to order a cup of tea, and say: "Just a quick call to let you know that your husband isn't dead. He left a message with the switchboard." Then he is gone before you can ask any more. Proof that what is going on at the home front has never crossed the mind of anyone in the newsroom. This is something that could be so easily remedied.

When Tim came back from Darfur with pneumonia and was in hospital for six weeks, the family income dried up and the phone was silent. No one cares about a freelance who can't work, even if his last assignment has made him ill. That is why part of the proceeds of my new book will go to the Rory Peck Trust, which helps the families of freelance newsgatherers killed, seriously injured or imprisoned in the course of their work.

Now, back to the spring of 2003 and not long after my trip to Tesco, it was my turn for a shock when ITN reported that Tim's hotel (which had been listed in that day's Evening Standard as a target) had been hit by a cruise missile. My 15-year-old son Ben sat me in a chair and grabbed the phone. "Don't worry it's ringing," he said. We were lucky. Tim answered. It was the building next door that had taken the direct hit, and he had just had room service delivered.

This kind of evening leaves you with a lot of emotions to deal with. Firstly, why does he have room service and I have to cook the kids' tea? Why is he doing something exciting and I am stuck in London?

My husband's hotel was a target, but how did I get him out of it and into safer accommodation? It was Friday night and everyone at The Economist had gone home for the weekend. One of the editors had given me a mobile phone number, but it was switched off. Eventually, the next day, I persuaded Tim to move to a safer hotel — the Hotel Palestine. I was lucky I had some good friends to support me, but it was a crisis that I had to cope with alone.

Modern technology has made it easier to resolve these issues. Now I can phone him direct on his satellite phone and scream at him because the washing machine is broken. On bad days, like the one he spent interviewing Kosovan-Albanian women refugees whose male relatives had just been murdered by Serbian forces, we talk about what he has just seen. He sounds flat and exhausted. This one-to-one contact not only keeps our marriage in one piece, I am convinced it has helped Tim stay sane while many other frontline reporters end up deeply traumatised. The only disadvantage with this therapy is that it can lead to expensive phone bills. That is why I feel that the industry has to do more to support the families who back up frontline reporters.

When it's time for the kids to go to bed, it's hard to read them a story as if nothing is going on, and dealing with their worries big and small takes hours of one-to-one parenting. These are the unpaid hours that back up my husband's ability to ensure that the news is reported accurately.

The way I’ve dealt with it has been by talking straight to the children about what is going on around them not packing them in cotton wool. It isn’t that I am a strange mother. My five children need the vocabulary to understand their world. They need to know what a cruise missile is and why not to be rude to a man at a roadblock with a Kalashnikov.

We were in Sarajevo the day the conflict broke out in Bosnia. Strolling around the city we heard the first shots of the war. I bundled 18-month-old Esti back into the pushchair and told Ben that was enough sightseeing for today.

Ben knew something was up and asked me what was going to happen next. Now, there is no parenting manual in the world that has an inclusion: “War is breaking out and the streets could run with rivers of blood. You need to say the following . . .” He fixed his eyes sharply on my face. I opted for honesty and told him the worst-case scenario.

Ben knew something was up and asked me what was going to happen next. Now, there is no parenting manual in the world that has an inclusion: “War is breaking out and the streets could run with rivers of blood. You need to say the following . . .” He fixed his eyes sharply on my face. I opted for honesty and told him the worst-case scenario.

Now he is about to graduate from university and wants to follow in his father’s footsteps. This summer he covered the war in Georgia. While he was there, he called me up to ask some advice. “I am really shocked by what I have seen but worse than that what do I say to these old ladies who have lost everything?” He asked me. “They tell me their stories and there is nothing I can do.” I was glad to see that he had learnt an important lesson. Although reporting something horrific can leave scars, the most important thing to remember is that you will never be as traumatised as the people in your story.