Caught in the Crossfire

Newsgatherers have become collateral damage in the blood-drenched politics of the southern Philippines. Dozens of journalists were among 57 reported slain in the Nov. 23, 2009 massacre in Mindanao.

It was, even by the standards of the blood-drenched politics of Mindanao, in the southern Philippines, a senseless – and needless – carnage. Clan warfare is rife on the island, where unlicensed firearms proliferate and battles for political office have been deadly. But the massacre that took place in the morning of November 23 was unprecedented in its gruesomeness and brazenness.

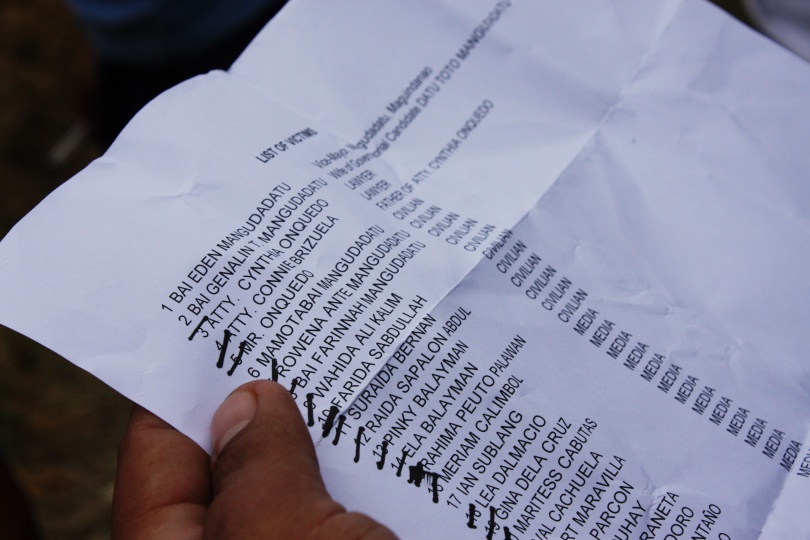

The latest press accounts say 57 people were killed, including 22 reporters, when about 100 armed men ambushed the wife of an opposition politician and her party.

Although he had been warned by his rivals that he would be attacked if he filed his candidacy for governor of Maguindanao, Ishmael Mangudadatu probably thought it was safe to send his wife, two sisters and two women lawyers – accompanied by journalists and his staff – to do the task for him.

A vice mayor and member of a powerful political clan in the province, Mangudadatu was poised to run against a mayor who is from the rival, even more powerful Ampatuan clan, in elections scheduled in May 2010.

Andal Ampatuan has been governor since 2001 and his family members monopolize political office in Maguindanao. He has four wives and more than 30 children, one of whom now hopes to succeed him as governor. According to the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, Ampatuan has consolidated his power through his family’s intermarriages with influential clans, his links to the current President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo and what amounts to a well-equipped personal army: some 200 members of a civilian militia recruited supposedly to fight Muslim insurgents.

Maguindanao lies in the heart of Mindanao and is the third poorest province in the country. With a population of about 600,000, mainly landless farmers, Maguindanao has been fertile recruitment ground for the Moro Islamic Liberation Front. Literacy rates here are lower than in the rest of the Philippines and there are few opportunities available to the local people.

Guns are easily available in Maguindanao. Jobs, however, are rare. According to a University of the Philippines study, young men, many of them left orphan by fathers who were casualties in the many conflicts that riddle the province, are recruited by civilian militias in their early teens. The militiamen are deployed not just against rebels but also in the internecine clan rivalries that take place here. They support themselves through crime. “From the interviews with the children, these range from kidnapping, extortion, instigating displacement, murder, torture, and drug trafficking,” the study said.

The journalists who were killed Monday were abducted and then killed by followers of the Ampatuan clan. They were collateral damage in the deadly spiral of violence that has gripped Maguindanao for decades. Rarely has anyone been held to account for the killings. Because impunity rules, the violence continues.

But journalists were not the only victims: the candidate’s wife, sisters, lawyers and staff were gunned down as well. The death toll is still being tallied as the Army searches for more casualties. But the real victims are the citizens of the province. The end of the conflict is not in sight and ordinary folk brace for what they fear will be another spate of violence in a place that has already seen so much needless bloodletting.