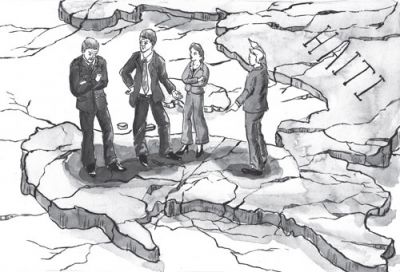

Five Years, Or Three Centuries?

Amy Wilentz, journalist and author of "Farewell, Fred Voodoo: A Letter From Haiti," reflects on the five-year anniversary of the earthquake in Haiti.

We’re all checking the news this morning, and noticing — in the margins of the reams of words on Charlie Hebdo and the 19th-arrondissement network — that it is the fifth anniversary today of the Haitian earthquake that took hundreds of thousands of lives in 2010.

Everyone wants to know how Haiti is recovering from that catastrophe.

It’s a good question that is more about how well the international community can deliver relief and recovery aid than it is about Haiti in particular. A brief answer to the question is this: some good was done with foreign help; a lot of rubble was removed; a few new buildings are going up that are seismically reinforced (a few of them are “luxury” hotels built by international chains); some good projects were started and some that were already in place before the quake have been bolstered by outsider contributions.

But the crisis caravan and the compassion economy also threw Haitians into disarray because their own initial efforts to help themselves were knocked out of kilter by the downpour of so much charity in such a short time offered by so many people who knew so little.

Here’s what my brilliant Haitian friend Louino Robillard has written about the immediate post earthquake descent of the foreign helpers:

The aid itself kept us off-balance. We didn’t know when the aid would be coming, when it would be going, why it was there, or what it would look like. It felt as arbitrary as the aftershocks, and we often felt just as powerless. We saw so many cars and logos and clipboards, and so little change. And we were at fault as well. That magical sense of solidarity melted into jealousy and competition over the tarps and tents that we knew wouldn’t be enough for everyone. Sometimes, we tore down the very things that people had built to help us, because we didn’t trust it. But when the very ground beneath your feet starts shaking, what can you trust?

For more of Robillard’s thoughts and words, click here.

Sitting here at my desk in L.A., and thinking about the minimedia fest going on in Port-au-Prince to examine the results of our blundering but well-meaning aid packages and programs, I’m a little perplexed at the continuing commentator focus on the earthquake-this and the earthquake-that.

Haiti is in crisis.

.jpg)

First of all, the usual political crisis: The photograph above, from belpoz.com, supposedly shows U.S. Ambassador Pamela White at the Haitian parliament last night, putting pressure on Haiti’s legislators to come to a deal with President Martelly on a new electoral law; according to the rumor mill, a deal was reached, which could mean that on the fifth anniversary of the earthquake, ie today, the Haitian government can go forward, Parliament will not be disbanded, the President will not rule by decree, and there will be legislative elections, followed by a presidential vote.

Don’t hold your breath. Last night’s deal was made without the input of the powerful Lavalas party, and as of this morning is still anything but certain.

So that’s the immediate political crisis.

But there’s a real and basic reason why Haiti — and countries like it — can’t be fixed, can’t be, in the memorable words of Bill Clinton after the earthquake, “built back better.” The problem lies in that passive voice of the hoped for results: that someone else is fixing Haiti, that someone else can build it back better, that scores of nice, good-hearted, kindly white people can fix the world’s first black republic.

My bottom line is this: You can’t fix it, because you broke it, and your mindset is the same now as it was 300 years ago, give or take a little bit of wisdom and little bit of harsh experience. Just looking at Pamela White trying to influence the legislature reminds me of this.

Haiti is the way it is because Haiti was always a plaything of the global economy, from its early heyday as a giant work camp of African slaves to its more recent iteration as an offshore manufacturing haven (low wages! no unions! easy corruption! practically China!) and possible package tourist destination. These are not terms on which a nation can truly be free nor a state truly establish upright institutions, pace the incredible and astounding successful Haitian revolution of 1791 that ousted the French. In the centuries since, the Haitian government has been conceived of and encouraged by outsiders (including the 19-year 20th-century US Marine occupation) to be a corruption creation device, a clacking machine that takes whatever clean dollars it can sweep up and sends them through obscure and shadowy gears until those dollars come out flaccid, filthy, and in the hands of the wrong people. Dirty dollars go into the corruption creation device as graft, and simply disappear. This makes it easy to run any old kind of business in Haiti, both for Haitians and foreign enterprises.

There are other, better ways to go for the country.

Haiti should be running its own agriculture and putting together cooperatives that export mangoes, sugar, coffee and rum for the international market. The Haitian state should have a five, ten and twenty year economic plan for the country that includes achieving a measure of self-sufficiency and detachment from the depredations of the rapacious global economy — if that is even possible in this era. But although Haiti grows some of the best mangoes in the world, the best sugar, the best coffee, when is the last time you saw a sticker on a mango that said “Haiti”? When is the last time, outside of Miami and Montreal, that you saw a nice silver bag of Cafe Rebo for sale? Put it down to the the corruption creation device. The only sugar produced in Haiti now (in a place where sugar was at the heart of the cruel slave regime and was produced by an international consortium until the mid-Duvalier era) is raised in small patches by single cultivators who sell raw cane as a roadside snack, and are not properly organized for profit.

I wanted to write a short post, not a complete history, and this is short, for me (ask my editors). Suffice it to say that the problems that have led to some 80,000 displaced people from the earthquake still living in temporary ad hoc camps in Haiti are the same problems we’ve seen since the days of the French colony. They are: a racist global economy, a condescending and yet exploitive global economic mindset, a prone, corrupt, and pandering Haitian elite, and the corruption creation device, which works for both sides. It takes two to create corruption: the corruptee and the corruptor.

So when you are looking at how the earthquake recovery effort has gone, don’t forget the two sides of that equation, and don’t forget the corruption creation device.

I met a kid in 2010, right after the earthquake, at a muddy rally at a new displaced persons camp near the shantytown Cite Soleil. He came right up to me with a piece of paper with his name on it and an email address. His name was Krushchev Rosale (not his real last name). Krushchev! How could I ever forget him? I have followed Krushchev’s progress since then — today is our fifth year anniversary, in a sense. Soon after the quake, Krushchev began taking English lessons. His English is now pretty good. His new Facebook image is of…. the real Krushchev. He is really smart but doesn’t have much means — some relatives in the US. I tried to set him up for jobs in Haiti with friends of mine in the relief effort, but those jobs, even the lowest of them, were really hard to get and very competitive. Now many of those jobs no longer exist as the crisis caravan moves on, and out.

Krushchev has also moved out. He didn’t want to live in one of the new shantytowns erected for earthquake refugees with the aid of the international community. He left Haiti for the Dominican Republic and is living there now in an ad hoc sort of way, trying to find work and some kind of useful education. Haiti is still pushing out its most resourceful people at all levels. If the international community wants to pat itself on the back for creating a handful of new Haitian shantytowns, well, go right ahead.

Yet five years after the earthquake (and you could have said this for centuries before), there is still so much left to do for Haiti and for Haitians, by Haiti and by Haitians. As my friend Louino Robillard might say, if you want to get it done, do it yourself.