In Hong Kong, Inhibition Turns To Protest

For the past two years, Kevin Sites, a 2012 Ochberg Fellow, has been teaching at the University of Hong Kong’s Journalism and Media Studies Centre. There, in large part to avoid being labeled problem-makers, his students rarely asked questions. For Sites, that's why the student-led protests in Hong Kong have been so remarkable.

I had been teaching at the University of Hong Kong, an English language institution, for two years before I had a clue to one of my most vexing problems: my Chinese students wouldn’t talk to me. They were unnervingly quiet. As an advocate of the Socratic Method’s emphasis on student-teacher dialogue, this was an educational apocalypse.

Part of the issue, I knew, was that in classrooms in both China and Hong Kong, the places the majority of my students came from, information typically flowed down, from teacher to student, like water being poured from a pitcher. Deference was also important. Asking questions could be considered rude or a waste of the teacher’s time. I wanted my students to question everything, especially me. They probably were, just not out loud. They were being polite.

I began to understand this conundrum more clearly when one of my students told me that that the written Chinese characters used to depict the word for question, wenti, were the same characters used to depict the word for problem. So, at least in writing, that duality might reinforce the notion that a question, instead of a path to understanding, might be considered a problem. Someone who questioned too much might be considered a problem-maker. Both were things better avoided in Chinese culture.

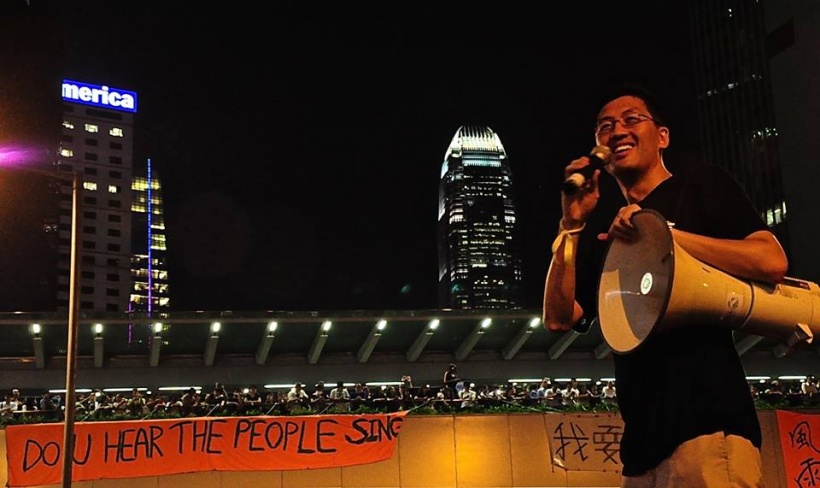

That’s why the student-driven pro democracy protests in Hong Kong over the last week have been so remarkable. Tens of thousands have shed some of the cultural inhibition against questioning authority and have spoken up, quietly, but forcefully. Why, they ask, should Beijing determine their political future?

But even their civil disobedience has largely been tinged in deference and courtesy. They print signs apologizing for the inconvenience their protest has caused local business with its occupation of great swaths of Hong Kong’s once seemingly bullet-proof business and financial districts. Far from angry anarchists, they sweep the streets up after themselves and recycle their trash. They sprawl their books out on Connaught Road and do homework in between rallies.

But even their civil disobedience has largely been tinged in deference and courtesy. They print signs apologizing for the inconvenience their protest has caused local business with its occupation of great swaths of Hong Kong’s once seemingly bullet-proof business and financial districts. Far from angry anarchists, they sweep the streets up after themselves and recycle their trash. They sprawl their books out on Connaught Road and do homework in between rallies.

And with little to no centralized leadership, they’ve managed a kind of logistical wizardry that efficiently delivers to protesters food, water and first aid services while stockpiling depots of surgical masks, rain ponchos and plastic wrap to help deflect the effects of pepper spray and tear gas used against them by police in the protest’s early days.

The umbrella, the protests’ most potent and enduring symbol came out of that clash when individual’s opened them against the dragon’s breath of toxic chemicals being aimed at their mucous membranes from the police barricades. It was a tool for defense, not aggression, wielded expertly by a movement that realized its power came from its apparent harmlessness.

“An umbrella looks nonthreatening,” said Chloe Ho, 20, in an interview with the New York Times. “It shows how mild we Hong Kong people are, but when you cross our bottom line, we all come out together, just like the umbrellas all come out at the same time when it rains.”

The quiet storm of the student movement has even broken through some of the interpersonal barriers typical of big cities, uniting people of different walks of life, who together, illuminate central Hong Kong most nights with the light of thousands of smart phones gently hovering overhead like fireflies.

The movement seemed to be having some effect. Midweek, CY Leung, Hong Kong’s Beijing-friendly Chief Executive finally conceded that a representative of his office would meet with movement leaders. But the leadership cancelled the talks the next day, after accusing the government of ordering police to standby while paid pro-Beijing thugs beat up pro-democracy students and reportedly sexually assaulted women in Kowloon.

No matter how polite and well intentioned, this has not been a completely victimless movement. Many local workers and businesses, from taxi drivers to small restaurants, have felt the pinch of the protest on their bottom line. While many endured it with a smile early on, the students and other protesters, some feel, are wearing out their welcome. To them, the questioning has indeed become a problem.

But it’s been a much bigger problem for Chinese President Xi Jingping, who needs to project a sense of unwavering Chinese sovereignty over Hong Kong and avoid special concessions to Hong Kong that might help the protest movement jump the borders to the Mainland. The timing couldn’t have been worse with the protest occurring over the National Day holiday celebrating the 65th anniversary of the founding of the communist Chinese state. Fireworks and other celebrations in Hong Kong were cancelled.

.jpg)

And while news of the pro democracy protests have been censored in the Mainland, the Beijing government has been watching warily and released a harshly-worded statement warning movement participants of “unimaginable consequences” if they persist with their activities.

Perhaps concerned that he needed to do something before Beijing did, Chief Executive CY Leung has ordered the protesters out by Monday… or else. Some school officials, mine included, have sent notices to their students and have made the rounds at the protest sites begging all to go home before they get hurt. “You’ve made your point,” they tell them.

But just as these students don’t always speak when I want them to, neither do they always listen. They have minds of their own, often preferring to show rather than tell. Regardless, their actions - and their umbrellas - speak louder than their words.

I just hope they’re strong enough to protect them from the storm that may accompany the answer to their polite, but insistent question.

-----

Kevin Sites’s latest book is Swimming with Warlords: A Dozen Year Journey Across the Afghan War. He’s and Associate Professor at the University of Hong’s Journalism and Media Studies Centre and a former Ochberg Fellow.