The Marshall Project's Akiba Solomon on Covering Incarcerated People

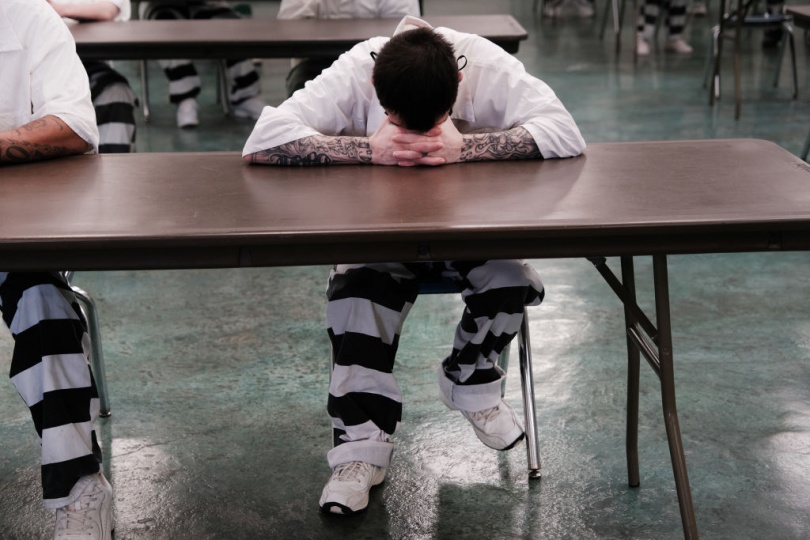

An incarcerated person waits at the Bolivar County Correctional Facility to receive a Covid-19 vaccination on April 28, 2021 in Cleveland, Mississippi.

Online editor Camille Baker spoke with Akiba Solomon, a senior editor at The Marshall Project, about "The Language Project," the publication's series on accurate and responsible coverage of incarcerated people. Solomon edited The Language Project and is an NABJ-Award winning journalist from West Philadelphia, who has served as senior editorial director at Colorlines and has written about culture and the intersection of gender and race for Dissent, Essence, Glamour and POZ. Solomon has also been a health editor for Essence, a researcher for Glamour and a senior editor for the print versions of Vibe Vixen and The Source. Solomon co-authored “How We Fight White Supremacy: A Field Guide to Black Resistance” (Bold Type Books, 2019).

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Camille Baker: Could you tell me about why you took on The Language Project?

Akiba Solomon: I joined The Marshall project in December 2019, and I edit the Life Inside series, which are the personal essays. When I got there, through a mutual friend, I met Rahsaan Thomas, who is the co-host of the podcast Ear Hustle now, and a journalist and activist in his own right. He's the chair of the San Quentin branch of the Society of Professional Journalists, and he was having a forum — come to find out this was the second forum where outside journalists could come and talk to incarcerated journalists about how to better, in their opinion, cover incarceration.

I had planned on going to the forum, but then COVID intervened and it was canceled. But Rahsaan was still really persistent, as was Lawrence Bartley, who is our director of News Inside [a print publication distributed in hundreds of prisons and jails across the United States]. Lawrence was incarcerated for 27 years, and when he got out, he ended up at The Marshall Project, but he also had really strong feelings about the use, particularly, of [the word] "inmate." I would say that those two colleagues really pushed me to do the Language Project at the time that we did it. Bill Keller, the founding editor-in-chief, had addressed language at the beginning of The Marshall project, but he stopped short of naming a style.

CB: Do you see The Marshall Project's guidance on language as kind of an outlier in journalism?

AS: I see the work we did as an intervention into an ongoing conversation. We didn't create anything new with the concept of using people-first language. I think what was new about The Marshall Project is just that we did it through the lens of journalism, through the lens of fairness and clarity rather than making it a political decision or trying to insist on jargon. We really wanted to make sure that we're clear about the language and why we use it, and that it's easily explained to people who might not be steeped in the world of criminal justice or those who are averse to some of the messaging that activists and advocates have put forth.

But for journalists, we need to understand and be clear about why we're doing something, and it can't be because there's a constituency who doesn't like the language we use, so now we need to change it. That's not what it is. But much of the feedback that we've gotten, honestly, has been behind the scenes. We had one Jersey-based journalist who just emailed me and was like, "I've written about criminal justice and had people get very angry with me and I didn't understand what the problem was. You really mapped it out. And now I'm going to be able to go back to my editor and have a conversation about it." I just talked to a major publishing house that is working on a book that involves prison labor, and they were trying to figure out the language. And [an editor there] found the Language Project and used that and said that it will inform their stylebook.

But most of the impact is about inward facing decision-making rather than people creating their own style and publicizing it or signing on to anything or making any kind of pledge. This issue has been bubbling for a long time, particularly after the uprisings of last year and the greater discussion around criminal justice, and how to cover people who in the past would just automatically be criminalized. The Language Project came at a time where more people were trying to grapple with this, because more people are covering criminal justice and thinking about how to interact with incarcerated or formerly incarcerated people. Instead of only writing about them, writing to them.

CB: Could you explain a little bit about how the media ended up here, why the prevailing instinct is to use language to describe incarcerated people in a way that criminalizes, marginalizes and labels them?

AS: I think there are a couple of things at play. Number one, much of criminal justice reporting in the past has been traditional crime reporting. And crime reporting is generally grounded in what police or law enforcement tell you. So police and law enforcement shaped the narrative, and as a result, they shaped the language. We see this happening in the most pronounced way with coverage of police brutality cases or police violence cases where people die, where the instinct of media and police departments would be to release the criminal records of the person who may have been killed or harmed. And essentially make it such that it becomes a way to justify the force that law enforcement may have used.

The growing activism and attention, and also just the greater access to information from groups that were previously marginalized — because they had no way to communicate — has changed the discussion. The folks who are incarcerated have access to JPay, which is a secure messaging system. Or you have groups like The Prison Journalism Project or The Empowerment Avenue Writer’s Cohort, where they actually have a direct line to media and they can speak for themselves and explain what the effects are of being reported on through the lens of police and law enforcement. So I think there's been a shift in how people cover criminal justice. I think there's a growing awareness and acknowledgement of systemic racism within the criminal justice system, and an understanding of how language can be used to dehumanize people, to justify the oppressive and unfair and sometimes extralegal parts of the criminal justice system. The Language Project and other things are a response to this growing awareness.

"There's a growing awareness and acknowledgement of systemic racism within the criminal justice system, and an understanding of how language can be used to dehumanize people, to justify the oppressive and unfair and sometimes extralegal parts of the criminal justice system."

But then the other thing, practically, is having Lawrence, who is the director of News Inside, and who actually came up with the idea of The Marshall Project’s print publication. A lot of media, I think, is about who's in the room and what your proximity is to who's in the room. He sat outside of my office. He and I would just talk as colleagues, which I think is really important. It speaks to why you need to have multiple voices in the room.

I’m probably showing my age, but when I started up in journalism, the internet didn't exist. So you could put things in print and it wouldn't follow you for the rest of your life. It would be on my microfiche, but unless it was the case of the century, you’re not going to find out if someone has an arrest for low-level crime. But in the time of the internet and social media and databases, it's incredibly impactful what you put online, because it stays there. That’s permanent, essentially.

Especially based on how algorithms work, chances are that the arrest, the incarceration or prosecution of someone is going to get attention and be considered newsworthy. Nobody ever writes an article about someone being cleared. People will Google you when you go for a job or when you go for an apartment or even if you go to an Airbnb, people are going to look up who you are. And if who you are, as per media, is someone who's a “criminal” quote-unquote, then that's obviously going to affect your ability to function in the world.

CB: If you had to give a grade to the mainstream media — major newspapers, TV networks — on their use of person-first language and fair coverage of the criminal justice system, what grade might you give?

AS: On the language piece, I would give a D, and this actually includes incarcerated people as well. I edit Life Inside and we don't change the language of our essays. Our essays use “inmate” more than any reporter pre-Language Project on our staff. Part of the project is to show also that there is no model around this. There are some incarcerated people or formerly incarcerated people who don't care. There are incarcerated people or formerly incarcerated people, who believe that “convict” is fine.

But I would say most mainstream media don't know about the issue, and even if they do, they're not going to change simply because “incarcerated people” is clunky — it’s longer, it's hard to work into headlines. People worry also about appearing to be advocates.

I think the language and the coverage of criminal justice sometimes are two different things. I've read plenty of articles that are deeply reported, where there’s a level of empathy for everybody involved, a commitment of fairness to people, that make sure to use reliable sources and not only come through the law enforcement lens. I see people being more careful and journalistically rigorous around reporting on these things, but they still might use the language of “inmate” or whatever.

"If the overwhelming majority of people in jail have not been convicted of a crime, then it is misleading to call that person an 'inmate.'"

The reporting on Trayvon Martin, where people tried to dig up things that he did to, in a way, justify what happened to him — I think that kind of reporting, to a certain extent, is a thing of the past. I don't think major media at this point are really falling for the same pattern of, “This person got shot by police. And now we're going to pull their criminal records and not say anything about, possibly, the record of the officer who killed that person.” I think people are just more aware and more rigorous in their reporting on criminal justice because this has become more of a central issue than it was before.

The other thing is, because there's so much media, you're going to find a million and one examples of balanced reporting and then you'll find a million and one examples of really flagrant reporting. Somebody would have to conduct a real media analysis to see where we are on this.

CB: I wonder if using person-first language in the media could have the unintended effect of masking the really dehumanizing practices going on in prisons and jails. How would you reconcile that?

AS: We’ve definitely heard that. One argument is, “You can call us ‘incarcerated people’ if you want, but we're still treated like animals and it really doesn't make a difference.” What I would counter is that what we're pushing for is, yes, terminology that is not unintentionally calling someone the pejorative without even knowing it. But also that there's a push for better, sharper storytelling and more specificity. It's almost like if somebody is a defense attorney and you're writing a story about them, but only call them a “lawyer.” That doesn't tell you information that you need.

Part of the person-first idea is to acknowledge the deep stigma that is attached to having a criminal record in this country. But also, two other pieces of clarity are: Number one, the way media has covered crime in the past has been like “There's a good guy and a bad guy. There's a victim, and then there's an assailant.” But we know that those things can all exist at the same time. A lot of people who are convicted of crimes have been victims of crime as well. The other thing is the number of people who are not convicted of anything being in jail. If the overwhelming majority of people in jail have not been convicted of a crime, then it is misleading to call that person an “inmate.”

I've argued that calling someone an “incarcerated person” doesn't mask what they did. It doesn't absolve them of anything; it's just a person who's incarcerated. And on the flip side calling someone an “incarcerated person” doesn't mean we're trying to use fancy language to make them sound more official or like better citizens or whatever you want to call it. That is the clearest possible language with, at least in my opinion, the least amount of negative impact.