How To Tell a Murderer's Story

In her book The Long Shadow of Small Ghosts, Laura Tillman examines the lasting effects of a deeply troubling crime—the brutal murder of three young children by their parents in the border city of Brownsville, Texas. Over six years, Tillman surveyed those surrounding the crimes, speaking with the lawyers who tried the case, the family’s neighbors, relatives and teachers, as well as one of the murderers: John Allen Rubio, whom she corresponded with for years. Over the course of their correspondence, Tillman wrestled with a series of tough questions: In the pursuit of a story, what constitutes manipulation? Is some degree of manipulation in this context inevitable? Is it wrong for a murderer to be gratified by the result?

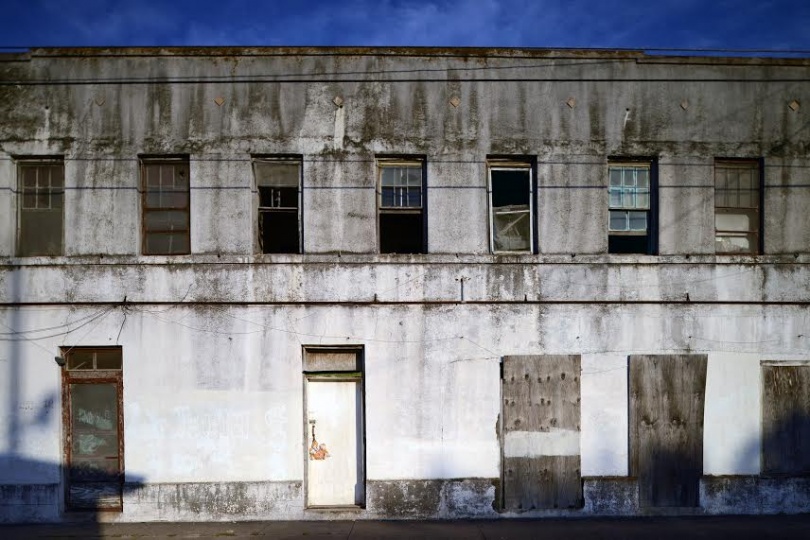

The apartment building located at 8th street and Tyler St. where John Allen Rubio murdered his three children.

This post originally appeared on Lit Hub.

In what must be one of the most incendiary opening sentences in modern literature, Janet Malcolm proclaims at the top of her seminal work, The Journalist and the Murderer, that, “every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible. He is a kind of confidence man, preying upon people’s vanity, ignorance, or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse.” She goes on to say that the subject reads the book that’s been written about them, expecting to find his or her story on the page—the story they have told to the reporter. Instead, they realize, the journalist “always intended to write a story of his own.”

I’ve gone back to Malcolm’s book again and again since I began my own correspondence with a murderer, John Allen Rubio, who remains on death row waiting for execution. John and his common-law wife Angela Camacho killed their three children in 2003, in the border city of Brownsville, Texas. John became instantly infamous, a “monster,” a communal villain. In comments on the newspaper’s website, residents of the city insisted he should be taken to the nearest mesquite tree and strung-up. Texan justice. I started writing to John after I’d begun chronicling a community battle over the fate of the two-story apartment building where the crime occurred, which many residents felt should be leveled. Eventually, I would include sections of John’s letters in my book, The Long Shadow of Small Ghosts.

In The Journalist and the Murderer, Malcolm investigates the lawsuit of Jeffrey MacDonald against Joe McGinniss, the reporter who wrote Fatal Vision about MacDonald’s case. McGinniss initially believed MacDonald’s assertion of innocence, but, over time, changed his opinion and concluded he was guilty. However, McGinniss did not inform MacDonald of his changing feelings, or the changing nature of the book project. Instead, he maintained that the book would exonerate MacDonald, a charade that went on for years. Malcolm was shocked and appalled when she read the letters McGinniss had written him. “They were so calculated, so manipulative and deceitful—and just so wrong, in terms of what McGinniss actually felt, as against what he wrote—that I had to wonder whether McGinniss had perhaps failed to tell the truth in his book. Those letters were very disturbing.”

When I wrote to John, I thought a lot about those letters, and The Journalist and the Murderer became a kind of warning. Writers disagree, as is proven out by McGinniss in the extreme, about what journalists owe their subjects. In the pursuit of a story, what constitutes manipulation? Is some level of manipulation endemic in this relationship, in which two people come together unnaturally, each with the hope of gaining something?

I kept my letters to John as businesslike as I could. They were pretty boring, actually—lists of questions, a few comments on the weather. He asked for gifts, I refused. He offered gifts, I refused again. When I interviewed him in person, I bought him food from the prison vending machine—a turkey sandwich, a can of soda, a pack of cookies. I sent him enough money to pay for stamps, paper, envelopes, typewriter ink so he could continue to write me. This amounted to 10 or 15 dollars a year. These decisions were all torturous for me. I don’t know if people outside the journalism profession can relate to this specific torture. You doubt yourself when you go out to lunch with a subject and find they’ve paid the bill without your consent. More so when you interview someone in distress and wonder whether it’s wise for him or her to give you permission to publish their name and photograph. Some of these decisions literally keep you up at night. This is the main count on which I take issue with Malcolm’s opening sentence. The idea that journalists on the whole act with no sense of remorse is simply not true.

Before I moved to Brownsville, I was an intern at a large news agency in New York. A month or so into my time there, I witnessed the delivery of a pie to the newsroom, a gift from a group who had recently come for a tour. I can’t remember if it was pecan or chocolate cream, but the presence of the pie undid the bureau chief for what, in my memory, was two hours. He tried to send it back to no avail. He tried to donate it, but, for whatever sanitary reasons, it couldn’t be gotten rid of. Finally, he was able to ferret out an arcane rule, allowing the acceptance of a perishable food item worth less than 30 dollars. Another reporter sidled up to the pie and announced the grams of fat and the calorie count, and then others took slices and order was restored. It was painful to watch, but wonderful.

John and my letters continued back and forth for several years. I wrote him lists of questions, he wrote back with humor and depth and openness. When I saw him in person I tried again to affirm that we were not friends. That was not the nature of my interest in him. I was a reporter, I was trying my best to tell a story accurately. It felt cruel, but it was the truth, and instilling some McGinniss-like hope that he would find vindication in my book was a trap I didn’t want to set for myself. I’d feel beholden and boxed in. He seemed to understand, and when I ran out of questions and the letters stopped, he didn’t write me frantically wondering what had happened to his friend.

My last letter to John was sent a few months back, advising him the book would be coming out soon. When it was published, I sent him a copy. A letter came to me a few weeks ago, in one of those familiar envelopes from the Polunsky Unit, opened and reviewed by a prison employee and then taped shut. John thanked me for the book, updated me on his case. And then, he wrote, “Before I close this out, I wish to tell you that I understand that we are not friends, that you were doing your job in a profetional (sic) way but to me you are an answered prayer as I have been wanting for my side to be hear (sic) for the longest time since this all happened.”

I felt relief when I read his note. But part of me bristled at the stamp of approval. I wouldn’t call my portrayal of John in The Long Shadow of Small Ghosts flattering—he does drugs, he’s an irresponsible father, and then he murders his children in a spectacularly gruesome fashion. But in the end, unlike MacDonald who always argued his innocence, John admits his crime and is remorseful. So, how potent is remorse? In The Journalist and the Murderer, some of those interviewed said they might have felt sympathy for MacDonald had he shown such remorse. Likewise McGinniss. If only he’d admitted he cared more about the success of the book than he did about being honest with his subject, they might not feel so angered by his deception. When people have told me their reactions to John and the book, it seems that this remorse allowed them to take his whole biography into account and view him as a human being. The letters he wrote me from prison were a big part of that. He’s emotional and childlike and his humanity emanates from the page. McGinniss, and Malcolm too, struggled with MacDonald’s dispassionate, even “boring” style of writing. While they had to battle to bring him to life as a full-bodied character, I battled instead to keep the persona of John’s letters in check as I weighed his own version against competing evidence, with the knowledge that he was an unreliable narrator.

In the afterword of her book, Malcolm writes,

There is an infinite variety of ways in which journalists struggle with the moral impasse that is the subject of this book. The wisest know that the best they can do—and most practitioners easily avoid the crude and gratuitous two-facedness of the MacDonald-McGinniss case—is still not good enough. The not so wise, in their accustomed manner, choose to believe there is no problem and that they have solved it.

With this, I tend to agree. I hear John say he knows I’m not his friend, but he is grateful, and I wonder if this represents success or failure on my part. I don’t see myself as being on John’s side, but if I was careful and fair in my depiction, is it wrong for him to be gratified by the result? As I check myself for the impulse to manipulate, I have to watch out for the same thing in my subject. Every time John acts magnanimous (“Hope your marriage is filling you with lots of love and contentment. It is only when we are in a relationship that we can feel more of a compleat (sic) person. At least I think so. Take good care of yourself and God bless”), part of me wonders if it’s by design. And yet, the book is done. What does he have to gain now?

Malcolm is critical of her own work; though she promises him nothing, her letters to MacDonald take on a tone she later finds cringe-worthy. This battle, this dissatisfaction and reevaluation, is ultimately her lesson for reporters. Her book is a product of the endeavor she critiques. Her queasy conclusion, that reporters’ hands are never clean, is agonizing. This battle to do better is ongoing, and it’s not just Malcolm’s. It’s shared across the world of journalism. In it, reporters find value, and an ever-deeper story.