Losing Gloria

A deeply humane and riveting piece that follows the Marin family through the arrest and deportation of their mother. Judges called “Losing Gloria” a “beautifully written,” “crucial story” that shows how people “metabolize the trauma of a singular moment.” Originally published in The California Sunday Magazine in June, 2017.

Angel and Yesi Marin with Yesi’s kids in the trailer park where they lived with their mother.

DISPONIBLE EN ESPAÑOL

It was just after school got out, on one of those blinding, bright days in Phoenix, when 10-year-old Angel Marin learned that his mom was gone. He was walking home from class with his older sister Yesi. They ducked through the iron gate to the largely Mexican trailer park where they lived and passed the blooming rosebush and the rainbow-rod swing set.

When they turned the corner onto K Street, they spotted their cousin halfway down their block. He shook his head as he cut toward them. “Don’t go home,” he said. Mothers stood outside their trailers, staring as the kids approached their double-wide.

In the living room, computer parts were splayed across the floor, the corduroy couches overturned. In the kitchen, food spilled from the cabinets onto countertops. There was a hole in the wall. Their mom’s sparkly blouses and blue jeans were thrown about. Their mother, Gloria, had been arrested, and the kids didn’t know why. “Nobody told us anything,” Yesi says.

Gloria Marin at her home in Nogales, Mexico.

On the morning after Gloria’s arrest, April 22, 2010, Evelyn, Yesi, Angel, and Briza pulled on their backpacks and left for school. They made a pact not to say a word to anyone — not their friends, not their teachers, not the kids at church. Angel knew that if he spoke, he could cry, and he didn’t want anyone to see. He kept his head down that day, and when friends asked him what was up, he shot back, “Nothing.” That afternoon, a manager from the trailer park came knocking. “You got to leave,” he told them. “We don’t want this kind of drama here.” The kids threw their clothes, movies, dolls, and video games into big black trash bags and set out from the neighborhood.

GLORIA, WHO WAS slight and wore her hair big and in a perm, came to Phoenix from Cuernavaca in 1992, when she was 17. She spent her first year babysitting for the woman who had taken her over the border, paying off her debt. Over the next ten years, she had her four kids by three fathers, who ended up either absent or violent. She found work cleaning office buildings and houses. On the weekends, before the sun rose, the family piled into their van and headed to a swap meet, an open-air market under tarps, where they sold toys and tamarind candy.

When Gloria landed a steady job cleaning and cooking for a Mexican woman in a wealthy part of town for $400 a week, things looked up. Gloria could now afford to pay for cable and Wi-Fi, and sometimes she could take the kids to eat at nearby strip malls. Then, two months into the new job, her boss called from jail and said she’d been arrested for a DUI. After the police came for Gloria, she says she learned the real reason: Her boss was accused of running drop houses — homes where undocumented migrants spent the night on their route north.

According to prosecutors, Gloria was an accomplice — “the errand girl.” Under Arizona law, she’d take on the same charges as her boss: from human smuggling to kidnapping to illegal control of an enterprise and more. Gloria says she was unaware of what her boss was doing, but the prosecutors didn’t require much evidence for the charges to stick. Gloria’s lawyer told me that in accomplice liability cases, prosecutors just need a convincing argument that the accused knew what was happening and that they were helping in some way.

Roughly half a million U.S.-born children lost a parent to arrest, detention, and deportation between 2009 and 2013. Most of those who lose a single mom or dad, like the Marins, move in with extended family or friends. But if no one is there to care for them, the child welfare system takes control. At the time that Gloria was arrested, Arizona’s Child Protective Services (CPS) had slipped into crisis. In response to the recession, the state had cut the agency’s budget and laid off hundreds of workers just as a swell of kids entered the system. The overwhelmed agency was soon ignoring reports of abuse, cutting children off from their families, and failing to provide mental health services. It is now the subject of a federal class-action suit that charges wide-scale mismanagement.

In Arizona, which has one of the highest rates of deportation, the kids of the deported face even worse conditions. They are often isolated in a foster care system that doesn’t know how to get them back to parents outside the U.S. Child protective agencies around the country don’t track how many children in state custody have parents who are detained or deported, but the most recent national estimate, from 2011, put the number at 5,100 kids and rising. These children are caught between the immigration and child welfare systems, both of which aim to reunite families whenever possible. But no clear policy exists for these kids, and reunification hearings can drag on for years. When the cases do reach the final stages in family court, children are often faced with an impossible decision: Stay in the state they call home without family or move in with a parent they haven’t seen in a country they do not know.

Over the first five months of Gloria’s incarceration, the Marin siblings bounced between the homes of friends and aunts, out of view of child services. First came Lety, their mom’s friend, who let the four kids squeeze onto one mattress. Then it was Aunt Sharon in Buckeye, an hour west of Phoenix, with new schools and constant supervision. Finally, Aunt Dora, with her own five kids, down the block.

The Marin kids visited Gloria in jail a few times, talking over low wooden dividers, her wrists chained to the table. After that, they mainly heard from her through postcards. “I hope you’re doing good, and I’m sorry that all this happened,” Gloria wrote to Angel in Spanish. He didn’t know whom to blame. Sometimes, Angel thought this was Gloria’s fault — the chaos of new homes, his loneliness and anger. At other moments, he worried that it was his doing; when he’d gotten frustrated with his mom in the past, he’d told her that he wished she’d disappear. “I didn’t know what to say,” he told me. Instead, he chatted about cartoons and scrawled “I ♥ u!” across hole-punched paper.

In December 2010, eight months after Gloria’s arrest, Yesi and Angel’s father stepped in, and Angel thought, for a moment, that family life might resume. Omar, who was from Honduras and drove a taxi for a living, had barely been around for years. Now he took all the kids to a small trailer on a dirt plot in Buckeye. When they lived with Gloria, each child had picked one color for the walls by their beds: turquoise and hot pink in one bedroom, canary yellow and rose in another. Here in Omar’s trailer, there was no paint, no music, no furniture — just three mattresses, one in each of the bedrooms.

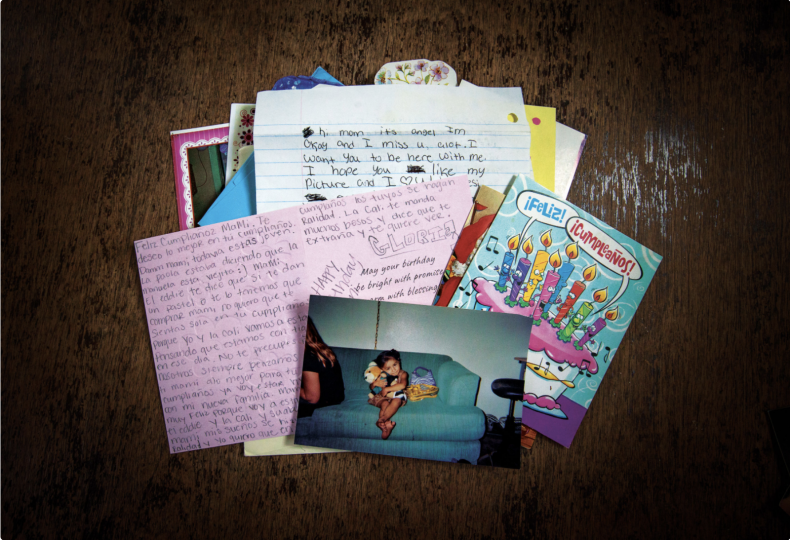

The letters and cards the kids sent Gloria while she was serving her sentence.

As the eldest, Evelyn took charge. In the afternoons she filled the house with friends. She hauled in speakers in lieu of chairs for the living room and improvised with groceries, crushing Chester’s Flamin’ Hot Fries over soup. They didn’t have any cash, only food stamps, so they’d have to steal. The girls monitored Angel’s asthma, too. If he started to wheeze, they’d boil a pot of water and hold his head above the steam. A school bus stopped out front for Briza and Angel in the mornings, but no one made the older girls go to class, so they didn’t.

Before too long, child services showed up. In February 2011, two months after Omar dropped them off at the trailer, caseworkers noted “bruises on children, no food in home,” and “children alone for extended periods of time, such as week or weeks.” Omar had coached Yesi to tell CPS that all was fine. If they weren’t careful, they’d be split up. Caseworkers didn’t come by often, but when they did, Yesi answered their questions with rote replies. “The thing was to stay together,” she says. “No matter how bad everything was.”

Yesi with her son.

Yesi stopped eating and stayed in bed; she wore only black, nails painted to match. When she found a single-edged blade in the trailer, she cut long slits down her forearms. She’d heard that was how she could kill herself. But just the sight of the blood let her cry, and that was enough. Evelyn’s crew was always filtering through the place, and when an older guy began appearing at Yesi’s door, she thought this could be her chance to start again. She’d never been with a boy before; she didn’t know how to kiss. “All I wanted was to be hugged, and to say, ‘Oh, I love you,’ and to have good meals together,” she says. When she let him know that she wanted a family of her own, he came on even stronger. If he keeps trying to be with me, then he loves me, right? she wondered.

Angel had always had a temper, but he started to snap more, punching the walls or lunging at kids when they bugged him. It seemed as though Yesi hated him. And Evelyn, she mostly spent time with friends. After school, Angel started hanging with a crowd that stole BMX bikes and car rims around the neighborhood. The rush of stealing made him feel alive, a break from all the drabness.

In the evenings, Angel watched cartoons with Briza, like He-Man and the Masters of the Universe, about a teenage boy who was called upon to defend his planet from evil forces. He was starting to think about girls, too. He had all these questions and no one to ask. He wondered what love was, and how you knew if it was real, and how, exactly, he could tell if people wanted him in their lives or if they were playing him.

Each night, the same dream haunted him: “Mom would be in the kitchen cooking, and I’d walk through the door and hear her moving dishes around, the TV on Telemundo.” He’d wake, feeling around for her body, which wasn’t there. He’d turn his pillow lengthwise and imagine that she was.

In the summer of 2011, Omar moved the kids to an apartment in Phoenix, and Evelyn ran away. (Evelyn did not talk to me for this story.) Yesi wrote her mom, pleading for help. “Hi Mom, I know I haven’t written you in a long time, but it’s because I don’t want to depress you with what’s happening,” the letter began. “I’m tired of crying alone. I need Mommy.”

Gloria could only reach the kids when Omar bothered to pay for the calls, which usually he didn’t. A corrections officer told her to read the Book of Job. Gloria was raised Catholic but had stopped going to church. Job’s story, though, seemed prophetic. He had lost his children, his house, his health. When he affirmed his belief in God, his world was returned to him. You shouldn’t deny God, Gloria thought. He’s going to give everything back. She read the Bible for hours and prayed on her knees three times each day.

In the fall, Gloria’s lawyer recommended that she take a plea deal. If she took the case to trial and lost, she could face ten years in prison. On the date of her sentencing, Yesi appeared in court. She took the stand and begged for her mother’s release. The judge sentenced Gloria to 19 months in Perryville Prison. Upon her release, she would be deported. She’d never be able to return.

Through Gloria, Child Protective Services had learned of Yesi’s letter complaining about Omar, and caseworkers started coming around weekly to investigate. They only questioned the kids in front of Omar — a violation of department policy — and Angel and Yesi didn’t want to get him in trouble or face his anger. “They made us feel like we’d done something wrong,” Yesi says of the caseworkers, “but we were just being kids and going with it.” Staff noted that there was still barely any food in the house and that Omar continued to leave the children on their own. After they found out that Yesi was pregnant and wasn’t getting prenatal care, caseworkers scheduled a series of sessions to coach Omar on the basics of parenting: safety, supervision, and health. But he rarely showed up, sending a girlfriend instead.

That the kids remained with Omar for a year wasn’t unusual. CPS was bogged down with reports of neglect and abuse. It was later made public that the agency had failed to investigate 6,600 reports. Only when Yesi started having contractions and Omar refused to take her to the hospital did CPS intervene. (The department declined to comment on the Marins’ cases.) On February 21, 2012, the afternoon that Yesi gave birth to a baby girl, Child Protective Services removed the kids from the home. They were now wards of the state.

Angel

The number of kids in Arizona’s care was hitting a record high that year. More than 14,000 children were in the system — a near 50 percent jump from 2007. After the recession-era cuts, the remaining case managers had, on average, nearly double the department’s recommended caseload of 20 out-of-home children per worker. A former caseworker in Phoenix told me that at her peak, she worked more than 55 cases at once.

As their legal custodian, Child Protective Services was responsible for providing the kids with mental health care. Between 70 and 85 percent of children in Arizona foster care have significant behavioral health disorders. CPS is supposed to ensure that kids are assessed for treatment; caseworkers are charged with taking them to their first appointments and overseeing the ongoing services. Within a few days of being at Alicia’s, “a rapid response team” had referred the siblings for appointments at a mental health clinic and left messages for their caseworkers. When the date arrived, though, caseworkers did not come by to take the kids; they never arranged to escort the Marins. A 2014 state evaluation would find that the majority of Arizona foster kids hadn’t attended their intake appointments within the required time.

Even though caseworkers had failed to take the kids to therapy, CPS hadn’t disappeared from their lives. Two caseworkers were assigned to the Marins, and they came around and asked questions every few weeks, checking on how they were doing. Angel and Yesi had been asking to visit Gloria for months, and a case manager finally took the kids to Perryville. When they got there, Gloria looked frail in her orange jumpsuit. Dark crescents hung under her eyes. Yesi handed over her baby, and Gloria broke into a smile through tears.

“You hungry?” Angel asked, gesturing to the vending machine, spilling coins onto the table. Yesi didn’t want to look sad, so she turned the conversation to music they used to listen to, laughing about Angel’s breakdance moves, how Gloria would blast Michael Jackson while the kids did chores. She didn’t want her mom to think they weren’t strong enough to be on their own. It was the first time that Yesi, Angel, and Briza had seen Gloria in close to a year. It would be the last time they’d see her in the United States.

Briza

A few weeks after the kids’ move, a man in a gray polo and khakis arrived at Martina’s, looking for Angel. “Dude, someone’s here to see you,” Angel’s cousin said, tapping him awake. Angel had never met the man. It turned out Angel’s caseworker was concerned he was on track to join a gang. “We’re going to put you in a program that helps boys,” the man said as Yesi and Briza looked on from the couch. “What do you mean?” Angel asked. He shot a glance at Martina, who wouldn’t meet his gaze. (Martina says she, too, was surprised.) Confused, Angel turned to pack a bag, but he was told to leave his things behind. We gotta do this shit alone now, he thought, climbing into the car.

ANGEL’S NEW home was Canyon State Academy, a sprawling brick institution for delinquent and dependent boys, on 180 acres in the desert valley of the San Tan Mountains. “Come on, get up, get up, time to wake up.” Angel jumped out of his bunk bed his first morning. The bedrooms had been stripped of doors, and staff were shouting down the hallway. The massive group home ran two programs: one for foster kids who needed a bed between placements, and another for kids caught up in crime.

At 4 feet 3 inches, Angel swam in his uniform, the maroon shorts slipping from his waist, arms like sticks in the too-large T-shirt. Canyon State housed roughly 350 boys, and at 13, Angel was one of the youngest. “He was a little different — a quieter guy,” his group leader, LaMont King, told me. Like the other boys, Angel had his head shaved and was expected to call the staff “sir” or “ma’am.” Each day, he and everybody else woke at 4:50 a.m. for a workout — crunches, push-ups, and squats in the dark before dawn. Then came breakfast, cleaning, class, and treatment groups, like anger management and “gang realization.”

Almost all the boys in Angel’s young offenders program had stories: They’d jacked cars, fought off meth addictions, ran robberies, assaulted cops. Why am I even here? Angel wondered. He hadn’t had any problem with the law. CPS was so overwhelmed by the number of kids entering the system that it couldn’t always find a foster family or an appropriate group home. He was also confused about why his caseworker had disappeared once he’d arrived at Canyon State; she was required to be in touch every four weeks. He says he only heard from her once in six months. Angel wasn’t a good student, but he was savvy. He sensed that in order to get by, he’d need a story of his own. He told the others he’d been with hardcore gangs, dealing heroin and bricks of coke.

Angel dreaded the weekends, when kids went home or talked to family. He rarely heard from anyone. He was allowed to speak with his mom and sisters, but coordinating with the prison was difficult. When he called his aunt’s house, she almost never picked up. Angel didn’t know it, but his caseworker had requested that the department assign Gloria an aide to help her see the kids every month. The visits, though, never happened. “Due to lack of resources, [Gloria] continues to be on the waiting list,” Angel’s caseworker wrote to the court.

Angel didn’t have a visitor for nearly half a year. To mask that he felt deserted, he shut people out. “I felt like people just got rid of me, unwanted,” he says, “and I didn’t want to associate with nobody, not even talk to my own family.” King told me that on visitation day, he could see Angel’s enthusiasm drop: “It’s like, ‘My caseworker isn’t getting in touch, I can’t talk to my family. You need to give me something to hold on to, because you’re not.’”

Angel began to anticipate what would set him off — basic “your mama” jokes would send him into a fit. Other times, his rage just took over. Once, a roommate tossed a pillow at him, and Angel felt his body stand up and run toward the kid, swinging punches and backing the boy into a wall. Angel didn’t want to lose control, and he liked it when staff complimented him on his better days. After a while he used the techniques he had learned in treatment groups. If he felt anger coming on — his skin heating, a stuttery glow of light around him — he would draw. He liked to sketch praying hands, and he’d pin his work to his corkboard.

When his thoughts turned more violent, Angel asked for therapy. It took weeks before he was enrolled for counseling. Soon after, his counselor left, and Angel waited weeks to see a new one. This delay was not a surprise to staff. Wait times for foster kids can range from two to six months in Arizona, and CPS caseworkers have no system that tracks whether their kids are getting therapy. Angel couldn’t sleep at night and stared blankly at the open doorway. Some days he fought back a taunting voice in his head. You keep telling yourself you got to keep going, but what’s left for you? it said.

Angel outside the jail where his mother was first held.

When a woman had arrived to take Yesi, Briza started screaming, “Please don’t leave me, don’t leave me here! Can you take me with you?” For months, Yesi could hear her sister’s words in her head. The Marin kids were now all separated. Briza was at her aunt’s. Evelyn was on her own in Phoenix. And Angel and Yesi were in group homes, 30 miles apart, with no way to know where the others were or where they might end up.

“What is this place?” Yesi asked the other girls when she arrived. She didn’t know homes like this existed. White baby gates partitioned the maze of hallways. Fifteen or so girls shared a one-story house, two to a room. Their kids slept in cribs by their beds.

No cell phones, no social media, no contact with anyone without CPS approval — the rules were clear. The problem for Yesi was that her caseworker hadn’t OK’d seeing anyone, nor had she authorized her to leave the compound. When the other girls went home for the weekend, Yesi was alone. “I didn’t have any contact with anybody,” she says. Staff tried to reach Yesi’s caseworker, but they didn’t hear back for nearly three months. “That unfortunately happens very often in the system,” says Emily Fankhauser, a staff member at Girls Ranch while Yesi was there. “Once girls moved into the group home, I’d tell them: ‘It’s going to be really hard to get ahold of your case manager. Please know we’re doing everything we can.’”

Yesi would walk around the vast backyard and try to peer over the concrete wall, where babies toddled around in an adjacent group home for infants. A housemate told her that a little-known dating site, MocoSpace, hadn’t yet been blocked on the communal computers. They created fake accounts and pinged their siblings. They’d sit at the screens for hours, waiting for a response. Eventually Evelyn replied, and once Yesi convinced Evelyn that it was really her, they could talk in short, typed exchanges.

After six weeks at the home, Yesi started therapy. She didn’t tell the therapist about her anxiety attacks, how she couldn’t be around too many people without feeling ill, about the time her teacher asked her to give a presentation and she vomited at the front of her class. She was afraid the staff would put her on medication and that CPS would take her baby away. The therapist asked her to close her eyes and think of the bad. When Yesi did, all she could see was Tarzan, another child without family, in a jungle. “What’s hurting you?” her therapist would ask. “I just want my mom,” Yesi said, over and over. She didn’t know if they had internet or cell phones in Mexico and was convinced she’d never speak with her again.

After a while it felt easier to forget the world outside the walls. “I was in this floating place,” she says. “I didn’t really think about anybody or anything.” Other girls acted out, throwing toys or slugging staff. “Her anger was quiet,” Fankhauser told me. “She wouldn’t blow up, but she could bring you to the floor with one sentence.” Yesi didn’t try to escape, because those who did usually left their babies behind. “I wanted a little girl ’cause I said, if I don’t have that motherly love, I’ll give it to her,” Yesi told me. Each night, Yesi crawled into her daughter’s crib to sleep, curling around her.

Yesi was provided an aide to help her prepare for adulthood. When the woman heard Yesi’s story, she snuck her a cell phone with instructions to keep it secret. Yesi finally reached Briza, who still lived with their aunt, but she says that Briza gave her one-word responses, like a robot, and she could hear their aunt breathing on speakerphone. The aide also escorted Yesi to a new therapist. She had one recommendation: Yesi needed to talk to Gloria.

Yesi didn’t know that around the time Angel first called her, Gloria and 15 other women were driven by van through downtown Phoenix, past Tucson, and into the Sonoran Desert. When they crossed the border into Nogales, the women filed out, clutching clear plastic bags with their only belongings. Gloria carried her court records, a packet of letters from her kids, and two 4-by-6 family photo albums.

She had wanted to fight the deportation order, but she couldn’t bear another six months without her kids while she awaited an immigration hearing. She also knew that with a felony conviction and with children who were healthy, she didn’t have much of a shot at getting the order reversed.

In Nogales, she sat in a room at the border crossing as officials coached the women on the exchange rate and the city’s public transport system. At the end of orientation, Gloria approached an officer. “My kids are in CPS custody,” she said. “How do I get them back?”

Yesi at her home in Phoenix.

As soon as she could, Gloria went to the office of Integral Family Development, Mexico’s child services agency, where she met with a lawyer who helped parents like her. “It’s going to be hard to get your kids back,” she remembers him saying. “You’re going to need a bank account, a house for your kids, and a good job with good pay.” A social worker in the office, who’d advised on dozens of similar cases, told her that she might not receive a final decision for a year.

There’s no data on how many parents who live abroad are trying to regain custody of kids in U.S. state care. Over the past two years, the Mexican consulates have advised on 4,600 reunification queries involving kids in the States, but that figure doesn’t distinguish custody cases between parents from those involving child protective agencies.

Coordinating a U.S. legal case with a parent across the border is complicated. Gloria’s social worker in Nogales told me that in roughly half of his cases it can take five months before child protective agencies release information on the specific services — parenting classes, psychological exams, home studies — that parents need to win their cases. On the U.S. side, many caseworkers don’t know which Mexican officials to call in order to evaluate parents. Sometimes they just don’t trust the assessments they’re given. These obstacles can make some parents feel they have no choice but to give up.

Gloria spent her first few months getting her Mexican ID, taking exams in Spanish for school credits, and eventually landing a job at a factory, assembling wire harnesses for automobiles and refrigerators; she made $4 a day. Through the Integral Family Development office, she took parenting classes to prove to the U.S. courts that she could mother her kids, and she paid for the required drug tests. Each month or so, she phoned into her hearings at family court in Phoenix. Sometimes she’d look out at the mountains by the border and imagine what it might be like to cross back.

At first, Yesi, Angel, and Briza all said they wanted to go with Gloria. The months stretched on, and Gloria called often. She sounded different. She talked about God on every phone call, and Angel felt far from her. “Like I didn’t really know her that well,” he says. She didn’t laugh at his jokes the way she used to, either, instead turning the conversation to tales of Moses and David. Angel still harbored anger, too. Maybe if she’d asked more questions of her boss, none of this would have happened. Angel knew if he said this, though, he’d hurt her. None of the kids dared start a conversation about how the separation had changed them. It was easier to fantasize about the future.

When Angel asked to see Gloria, his caseworker said it wasn’t possible. His sisters couldn’t get permission, either. In much of Arizona, caseworkers don’t receive training in how to arrange visits with a parent who’s across the border. The Mexican consulate can escort kids, but the logistics are difficult: Most government offices close on the weekends when kids are free, and the children need a court order before they can go. One former case manager, who has worked with approximately 20 kids in these circumstances, told me that, at best, the children saw their parents once a year.

Nogales, Mexico, from the U.S. side of the border. Gloria and Briza in their home in Nogales.

It’s so free, Briza thought as they drove through Nogales. Crowds gathered on the sidewalks; musicians sang in the restaurants. Angel noticed the signs of poverty — the slipshod concrete homes and the pocked roads. “Who do you live with? Do you have enough food?” he asked Gloria. Angel kept hugging her. Gloria told them not to worry, and to behave so they could be back together again soon. Then, four hours later, it was over. The kids were in the car headed north, a thick rain glancing off the hood.

In Arizona, the siblings waited for the court order as Gloria’s case for reunification proceeded. When Briza got anxious at her aunt’s, she sat on her bed and spoke out loud to herself: “It’s all going to be okay. We’re going to be a family again.” Yesi told her case managers that she wanted to live with Gloria, but they said she couldn’t. She was now 16 years old, a young adult, and she had to think about her child and finishing high school. Yesi could have pushed back but didn’t know it. “I don’t know why they didn’t want me to go,” she says. “But I was also so scared. I didn’t know what to think or what to expect over there. I was in fear of — well, what is she going to be like? Is she going to be the same?”

Angel was also torn. He wanted his mom, but like Yesi, he was scared. Mexico was dangerous — that’s what he’d heard, at least. He figured that even if he went, his family would still be separated; Yesi and Evelyn were likely going to stay in Phoenix. Mainly he thought about how hard life was for Gloria in Nogales. She was barely able to support herself. “She’s like a goldfish,” he told me. “She used to live in a tank full of other goldfishes and, what do you know, she got used to them, and out of nowhere she got dumped in the ocean.” He didn’t want to be another burden.

On the day before one of the final hearings, in July 2013, Angel called his mom. He was nervous. He knew he was adding more pain. “You’re always going to be my mom. I’ll never forget that,” he said. “But I’m going to say in court that I don’t want to go to Mexico.”

On August 17, 2013, three years and four months after Gloria was arrested, 10-year-old Briza Marin was the only sibling who crossed into Mexico. Her caseworker drove her to the steel fence that snakes along the border at Nogales. She walked down a pathway to a metal revolving door and pushed it clockwise to reach the other side.

Gloria and Briza in Mexico.

IT TOOK Gloria and Briza about a year to get to know each other again. They’d hardly been able to talk on the phone while Gloria was in prison — Briza says her aunt hadn’t let her, and when Gloria complained to the caseworker, nothing changed. By the time Briza got to Nogales, she had lost most of her Spanish, so the two pieced together broken sentences. Briza was distant and moody — not the cheerful talker she’d been at 7. She stole money from Gloria’s purse. She talked back at school and got into fights. Gloria kept sitting her down at their kitchen table. “I’m doing everything I can,” she’d say. “This is your home. I don’t want to hurt you.” For months they shared a bed, and each morning Briza watched as Gloria rose at 3 or 4 to get ready for work. Slowly the distrust that Briza had built up while living at Martina’s began to recede.

Angel graduated from Canyon State in 2013. He was the smallest kid to ever make it to ram status, the institution’s second-highest honor; the staff had an impromptu meeting on how to order an extra-small jacket. After he graduated, Angel moved in with his Aunt Sharon, along with her five kids. In the early months, he was polite and reserved. The old Angel re-emerged, Sharon says, his jokes and his energy and his protective ways. His anger came back, too, and he’d sometimes pick fights at the slightest irritation, reducing his cousins to tears. He says that he feels like his depression will always be there, like “a sweater you wear every day.” Earlier this year, he left Sharon’s house. He’s now sharing a room with Omar, though Omar’s rarely there. He plans to be the first of the Marin siblings to earn a high school degree.

Angel muses often about how losing his mom has changed his understanding of love. “I don’t know what love is,” he says. “They tell me you’re supposed to love your mom, and I say that I do, but I don’t know that love is supposed to feel this way. I feel so empty.” Sometimes he talks to Gloria about how his love has faded. He doesn’t know what to do, and he doubts if he’ll ever have romantic love, either. He still can’t sleep much — only when there’s another person lying in bed with him. When he visited Nogales for the first time after Briza moved there, he lay down next to Gloria. The touch of her hand on his arm sent him to sleep for ten hours. He says it was the first night that he slept all the way through since her arrest.

As for Yesi, she’s now 21, married with a baby boy as well as her daughter. She is still big-eyed and babbly, as if by talking through her story she can make sense of it. After a year at Girls Ranch, she was moved to a new group home without warning, and later to live with Evelyn in Phoenix. In the spring of 2014, she took her 2-year-old to Nogales to see her mother and Briza. It was almost as if nothing had happened, like she was a kid again with her mom. “I thought home was that trailer,” she told me. “But home is wherever she is.”

Yesi thought about staying. She could get a job on the Arizona side of the border and spend the nights with Gloria. She regretted not going to Nogales sooner, when Briza did. But her daughter’s dad was in the U.S., and she had school to finish. Life was in Arizona. So four months after she arrived, she caught a bus back north. When she got to Phoenix, she spent a week in bed, ignoring her mom’s calls. She didn’t have it in her to hear her voice.