Camp Z30-D: The Survivors

Written with grace and restraint, these stories of Vietnamese men and women imprisoned for “re-education” reveal their suffering in the camp and their struggles as refugees in the U.S. Originally published in the Orange County Register on April 29, 2001.

"I'm sorry, so sorry," he says. "Soldiers don't cry."

But his shoulders contort, his body racks with sobs. His hands try to wipe away the tears.

"Please forgive me," murmurs the former lieutenant colonel, shaken by memories of nearly 13 years in a prison camp. "This is what re-education does to you."

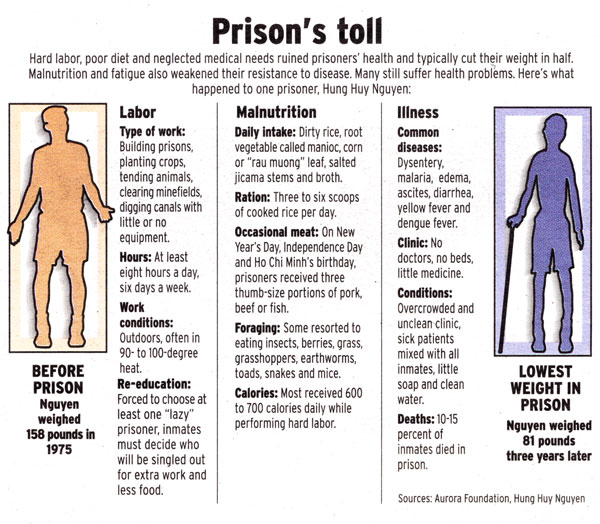

Hung Huy Nguyen, 71, along with an estimated 1 million South Vietnamese, is a man who came to know death and torture in the years following a war that tore apart families, countries, generations.

His was a world where friends died suddenly. Violently. Where others slowly wasted away from malnutrition and disease. Where stealing a grain of rice led to lashes on the back, down bony legs. Where men and women silently endured, night after night, grasping at hope that someday they might see their children again.

There are no official figures on how many prisoners were executed or how many died from poor treatment. There are no known government records of who was sent to the "re-education" camps, or for how long. There are no archives on the jails, or of what went on. Such are the ways of war, and the treatment of those on the losing side.

A four-month review by the Register of these camps, however, shows a widespread pattern of neglect, persecution and death for tens of thousands of Vietnamese who fought side by side with American soldiers.

To corroborate the experiences of refugees now living in Orange County, the Register interviewed dozens of former inmates and their families, both in the United States and Vietnam; analyzed hundreds of pages of documents, including testimony from more than 800 individuals sent to jail; and interviewed Southeast Asian scholars. The review found:

- An estimated 1 million people were imprisoned without formal charges or trials.

- 165,000 people died in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam's re-education camps, according to published academic studies in the United States and Europe.

- Thousands were abused or tortured: their hands and legs shackled in painful positions for months, their skin slashed by bamboo canes studded with thorns, their veins injected with poisonous chemicals, their spirits broken with stories about relatives being killed.

- Prisoners were incarcerated for as long as 17 years, according to the U.S. Department of State, with most terms ranging from three to 10 years.

- At least 150 re-education prisons were built after Saigon fell 26 years ago.

- One in three South Vietnamese families had a relative in a re-education camp.

Vietnamese government officials declined to be questioned but agreed to release a statement about the camps:

"After the southern part of Vietnam was liberated, those people who had worked for and cooperated with the former government presented themselves to the new government. Thanks to the policy of humanity, clemency and national reconciliation of the State of Vietnam, these people were not punished.

"Some of them were admitted to re-education facilities in order to enable them to repent their mistakes and reintegrate themselves into the community."

Officially, 34,641 former prisoners and 128,068 of their relatives fled to America, according to the State Department. At least 2,000 former inmates live in Orange County.

And the legacy of the prisons continues today.

Authors, artists, journalists and monks are routinely arrested and jailed across Vietnam, human-rights activists say.

In Orange County, many former inmates wake up in the dark, shaking from nightmares. Others find themselves sleepwalking, aimlessly wandering. Some live in fear, trusting only family.

Dozens of former prisoners declined to be interviewed by The Orange County Register, saying they worry about reprisals against relatives who remain in their homeland. Most asked not to be named.

Some agreed to tell their tales, then hid when they heard knocks on the door. Still others shared their stories only to regret it later, the searing memories too much to bear.

In refugee enclaves throughout the United States, anger and hatred toward the Hanoi government are common. There are ongoing boycotts of Vietnamese goods, especially in Orange County, where more than 250,000 immigrants settled, forming the nation's largest Vietnamese population.

Some survivors, however, are beginning to speak out, to give testimony to their treatment and to those who died.

To offer a full and authoritative picture about what re-education meant, this project tells the story of life in one prison – Camp Z30-D – jail to thousands of the highest- ranking officers in the South Vietnamese army.

Patriotism

The government rounds up hundreds of thousands, saying they will be released in 30 days.

|

HUNG HUY NGUYEN |

Hung picks up his belongings: three sets of summer shirts and khakis, mosquito netting and enough money to cover meals for a month.

The lieutenant colonel slowly rides one of his son's bicycles toward the roundup area.

His wife and children appear smaller and smaller, fading into the distance.

“It seems like they are disappearing from my life,” Hung thinks. “Forever.”

He glances back, one last time.

His loved ones try to show brave faces, but their lips quiver, their eyes swell with tears. It is June 10, 1975, and nothing in their world has been right since April 30 - when communist tanks rolled past Hung's house, soldiers waving Viet Cong flags, red with gold stars.

Hung's military office, where he headed a press staff of 65, is trashed and taken over by the new government. He dares not enter.

Within weeks, every man and woman in the South Vietnamese military, as well as anyone ever affiliated with South Vietnamese or U.S. forces - village chiefs, translators, religious leaders, intellectuals - receives a special government summons. About 2.5 million in all.

The decree: Present yourselves in “genuine remorse,” undergo political re-education in a classroom setting so you may return to society. The process, the new government promises, will last three to 30 days, depending on rank.

Hung's typed summons orders him to appear at a school 3 miles away.

The night before he leaves, Hung, his wife and their children sit down for what they fear could be their last supper together as a family. Rice, catfish and sweet-sour soup. But no one eats much. Questions fill the air.

“What if we had made a dash for one of those ships or planes headed to America?”

Hung explains that duty and honor - age-old traditions - required him to stay.

“Should we have stashed away money for a crisis like this one?”

Too late.

“Who will save Hung from prison, or worse, death?”

No one knows.

Hung pushes away his saucer of soup and turns to his wife.

“What do you think? Should I go?”

“You don't have a choice,” she says quietly, adding, “When we first met, who might imagine it would come to this?”

“We promised to be together forever,” Hung says, “and now we might never see each other again.”

“How can you talk like that in front of the children?” she interjects.

But Hung can't stop. “If I don't return in a month, consider me dead. Do whatever you need to take care of yourself and the family.”

He turns to one of his adult sons: “I hand over to you my property and savings. You must be brave for the others.”

And to his eldest daughter: “You're old enough to be a second mother. Remember your duties.”

Both children, ages 32 and 31, nod solemnly.

No one in the family knows that Hung's wife is pregnant with a seventh child.

After riding the tiny bicycle through dusty streets lined with jeeps and tanks, past buildings crumbled by bombs, Hung reaches the designated spot - the former school.

Thousands are already there. Most are dressed in their best clothes, hoping to make an impression on the new government and offer a gesture of reconciliation.

As darkness falls, commandos arrive and load the men and women into covered trucks. The convoys rumble through the night. In the morning, the trucks finally stop.

Half-dazed, Hung stumbles off. Guards shout. A rifle butt shoves against his spine.

Hung can barely comprehend what is happening. He is dizzy, his throat parched.

The heat suffocates - like “a giant who squeezes you and won't let go.” Dust hangs in the air, along with the thick humidity of the Southeast Asian jungle, a combination of rotting foliage, musty fungus and muddy ground that never dries. In a clearing there is an abandoned, bombed-out military post with a few farm huts. Beyond, there's nothing but thick, dark vegetation, so dense that sunlight can't penetrate through the treetops.

Hung doesn't know it, but he's looking at what will become Camp Z30-D, one of the largest re-education prisons in Vietnam.

“Welcome to your new home,” a guard declares. “You're expected to furnish it well.”

The communists did not have time to construct full prisons, Hung says, “so in some areas they made us build our own. Every nail and post.”

By day Hung marches into the fields, guards watching over the inmates, divided into groups of 10. They clear land, cut wood from the jungle, erect guard towers two stories high, build barracks with platforms that sleep as many as 200 prisoners.

The 30-day deadline outlined in the summons goes by without comment. Everyone is too afraid.

Hung grimly thinks back to his childhood in the North, before his parents fled to the South. His father, a diplomat, would instruct his only child: “Give. Give all you can to your country.”

At the end of the work day, Hung is required to read communist doctrine, Ho Chi Minh, Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin. He writes his life story over and over in pencil on small notebooks, confessing his “faults.” To help him get through it, he reminds himself of his training as a cadet in the South Vietnamese army. Known for his efficiency and fair style, he was sent to France for combat training, to New Jersey for tactical strategy. He remembers how he fell in love with New York, riding the subway and eating hamburgers.

Later in the evening, he is herded with other inmates under the stars to a central courtyard. They sit or squat on the ground, listening to communist ideology for hours over tinny loudspeakers.

“Americans are perpetrators of evil.

“There is, and always has been, only one Vietnam.

“You are a menace to society. That is why you need re-education.”

He joins his “comrades” in circles, critiquing one another's work. After 15 minutes, each group must pick the “laziest” prisoner for special treatment: no breakfast, longer hours in the fields, extra manifestos to memorize.

“You cannot comprehend the paranoia of thinking: `Will I be singled out by my comrades today?' '' Hung recounts. “That happened day after day.”

Guards use bamboo canes and rods to beat prisoners who fall asleep or refuse to answer questions. They tie up men and women. Corner them against a wall. Shove them to the ground. Trample their bodies. Kick their heads.

The students call it “ Blood University.”

Inmates are required to store urine and feces under bunks, then carry the waste to the fields for fertilizer. “The crops grew up all puny and yellow,” Hung remembers, recalling how the stench filled the barracks.

As the months go by, prisoners form alliances, despite the daily singling out of a “lazy” prisoner. In response, guards develop a system of informants, rewarding them with extra food, separate sleeping rooms and other privileges. Eventually, the government scatters hundreds of prisoners to different camps to break up some groups.

Hung is relocated to a prison in the frigid mountains of the North. He finds himself assigned to plant vegetables with four other inmates. They quietly chat, sometimes sharing a match for a rare smoke. One evening, Hung offers them room under his mosquito net. They stay up late, bony bodies pressed tightly against one another for warmth, whispering confidences:

“I doubt if God hears our prayers,” one says.

“I sure miss my wife and my newborn boy,” another says. “Haven't heard from them since we left the South.”

“The guards say my wife will arrive soon for a visit. Maybe yours will come, too,” Hung consoles him. “I wonder what kind of world they're living in now.”

Eventually, the short winter days of 1978 turn to the brutally long, hot days of summer. One morning, Hung wakes to discover his friends have escaped. Hunting dogs bay in the distance. The warden orders everyone locked down inside the barracks.

Guards rouse Hung off his bunk and march him to the warden's office.

“You know why you're here,” the warden begins, “so save us time by confessing.”

Hung looks his interrogator in the eyes.

“Sir, I have no idea.”

“Don't play innocent, prisoner. You helped your friends flee. You gave them matches and cigarettes for their journey.”

“Sir, they told me they had run out of them,” Hung replies, his fingers intertwining with nervousness. “I had no idea. Really, I didn't.”

“Well, lie all you want. Those three won't run far in the mountains surrounding this camp. They'll be caught, and you'll have a surprise waiting for them.”

Two days later, there are rumors the escapees have been captured. Guards escort Hung and two prisoners to a nearby hill. They are ordered to dig small cave in the hillside. Hung grips a shovel and breaks earth. He starts to shake.

That next morning, screams pierce the dawn. They come from the area where Hung was digging. A few prisoners report seeing one of the escaped inmates beaten to death in the first cave. They say his body was dumped in an unmarked grave nearby.

Later, Hung learns the other two inmates were shackled in the caves for six months.

Epilogue

The veteran speaks slowly, pausing for reassurance. His legs shuffle, thin, like chopsticks. He is nearly blind from cataracts that went untreated for years in prison.

Hung Huy Nguyen, now 71, won't be called withered, though.

“That term fits my prison years,” he says. “I was a walking ghost.”

His time behind bars: 12 years, 363 days, eight hours.

After his release in 1988, Hung made his way to the United States - first to Cedar Rapids, Iowa, where the winters drove him to Orange County. He and his wife settled in Fountain Valley with their children and grandchildren.

He joined a work program for seniors, first helping at the Department of Motor Vehicles and later at Catholic Charities. He retired two years ago. Now, most days find him baby-sitting two of his grandchildren or typing his memoirs.

He writes anti-communist essays for local Vietnamese newspapers. He talks to community groups, reminding them of their countrymen still in Vietnam.

“Life should be a model of service to others,” Hung explains. “You cannot truly live if others dwell in misery.” He is sobbing heavily.

Through the tears, he searches to make sense.

“We didn't choose this suffering. But if some good comes out of it for the next generation, then we have found redemption.”

Endurance

|

TRACH DUC NGUYEN |

Trach Nguyen squints across the dirt courtyard. The voice on the loudspeaker drones on about the merits of communism. The twilight is dwindling.

The tiny library. The primitive kitchen. The poorly equipped clinic.

He fights to stay calm.

He follows the line of prisoners toward the barracks, guards shouting at the stragglers.

His heart pounds.

He passes the meeting hall, another night of political lectures finally coming to an end.

His chest heaves.

He must choose the perfect moment. Suddenly his body is enveloped in the black shadow of a building. He silently slips out of line.

He zigzags from tree to tree, making his way toward the first fence surrounding the prison.

Seconds later, Trach's friend An catches up. Suddenly, two men emerge out of the darkness. Trach's mind spins. Then he realizes they are prisoners, not guards.

The pair overheard their whispered escape plans during dinner the week before. Desperate, they have promised to keep quiet, but only if they can come along.

Trach relents, motioning for silence. He lifts the barbed wire, crawling through one metal snarl, then another. The metal spikes tear his skin. He keeps going, across the small clearing and into the darkness of the jungle.

After two hours, the faint barking of dogs breaks the rustle of leaves and branches.

“Oh no, they're already on to us!” An says.

“Don't panic. We'll elude them,” Trach whispers.

"It's going to be tough," An says. "If we're caught, you know we'll be dead."

"If we come across any strangers, you all know what to do — right?" Trach asks.

"But none of us has ever ..."

"It doesn't matter," Trach cuts in. "Anybody who finds us, we'll have to kill them with our knife."

Trach has fashioned the knife from a piece of scrap metal. He carries little else: a blanket traded for cigarettes, some dried noodles from home and 12 chloroquine pills, 500 mg each. Two can ward off malaria. An overdose can be fatal.

It is the middle of April 1976 — nearly a year since Camp Z30-D came to life in a Southeast Asian jungle.

After almost 11 months behind prison fences, Trach is a free man. The group travels by day and sleeps under a starlit canopy of branches and vines.

"Anything is better than the hell of prison," Trach says. His mind wanders to the comfort he knew as a child, reciting his father's poetry in kindergarten and writing his own stanzas by second grade.

He thinks back to the prison, recalling how guards would grill him for hours. Any allies still in hiding? Which inmate is talking rebellion?

Still, he was lucky. He saw others beaten with thick bougainvillea branches studded with thorns, leather belts, chains from broken bicycles. He saw guards tie up some prisoners so tightly that the rope cut into their hands and ankles until the hemp was wet with blood. Gangrene sometimes set in. Limbs were amputated.

He remembers how prisoners deemed "lazy" saw their food rations slashed, forcing them to subsist on little more than a thumb's length of cassava root. It tore Trach apart to watch defeated generals arguing over a few spilled grains of rice, grown men crying over lost families.

"If we hadn't fled," Trach tells An, "we would have died. We couldn't last long under those conditions."

The men push on through the jungle. They plan to reach a village 20 miles away that they've heard is friendly to South Vietnamese army veterans. There, they hope to get guns and flee to Cambodia.

"Tread lightly and rub away your footprints every so often," he cautions. "When you cross a stream, walk backward so the guards will think we're headed in the opposite direction."

By the fourth day, they are nearing the village and discussing strategy — food and water low, but spirits high. Suddenly, something moves in the foliage.

A boy, about 15, emerges.

"Who are you?" Trach shouts.

"Just a boy out collecting firewood. And who are you?"

The prisoners' grimy faces, matted hair and stained clothes give them away. Camp Z30-D.

Trach pulls his knife. The other inmates hold down the boy.

"Please, please let me go," the boy pleads. He explains that his father is also in prison for serving in the military. He says he is the eldest in his family and must help his mother.

"I promise I won't tell," he cries.

Should they tie him up? Take him with them? Follow the boy home and use him as a hostage?

They look to Trach.

"Desperate as we are, we're still human," Trach says to himself.

They free the boy.

"Remember," Trach yells as the boy runs away, "remember your promise!"

A few hours later, they hear the dogs. By nightfall, they are surrounded. Guards open fire. Two of Trach's companions go down. An shouts he is surrendering.

Trach looks at the 12 pills in his hand. He swallows them and raises his arms.

"I'd rather kill myself," he mutters to the guards, "than live in prison like an animal."

An hour passes. Then a day. Then two. Trach hallucinates, but his dehydrated body prevents the poison from spreading. He's dragged back to Camp Z30-D. Guards strip him naked and shove him into a Conex box, a container the U.S. military used to transport supplies. He can't stand up and can barely lie down. The narrow box is less than 5 feet long.

He's too weak to raise his hands. His legs are shackled. The stench of his own waste is overwhelming. Mites and lice dig into his skin. Temperatures soar under the scorching sun, then plummet during the night. Sometimes, guards beat on the containers with sticks, hour after hour. For six weeks, Trach falls in and out of consciousness.

His mind plays cruel games, seeming to mock him by reminding how he and his buddies once talked of joining the military so they could meet different types of people, bond amid the hardships of fighting and shape their lives through grand adventure. Serve for three years, finish college, teach literature. That was the plan.

Trach wakes to find the warden screaming. Every detail of his escape must be divulged. He is sure he will be executed by firing squad when there are no secrets left.

"I prayed to die," he says. "Yet something in me wouldn't accept defeat. Something in me still wanted to live."

Epilogue

After a month in the Conex box, Trach is suddenly moved to another prison, caught up in a mass transfer of inmates to the North. Nine years later, he is released, falls in love with a street merchant and marries. They emigrate to Orange County in 1991.

Trach now works the second shift as a machine operator at an electronics assembly plant in Anaheim. His wife, Van, sews dresses and jackets in the kitchen of their two-bedroom Anaheim apartment. On weekends, they drive their two daughters — Julie, 8, and Quynh Dao, 13 — to Vietnamese language school.

Because of his night job, Trach is unable to follow his parents' example and hum lullabies to his children. But he recites to them every poem their grandparents sang. And Trach still writes his own poetry, telling of his suffering in prison, of dreams vanished or delayed, of aspirations for his girls.

Trach, 58, longs to revisit his grade school, embrace his mother and find old friends such as An. He writes:

"Follow the clouds, sleeping above my hometown

"My town, Saigon, from my age of innocence

"The place I have known, known every rock and crevice

"Known the schoolyard, worn out from play

"Known the lyrics, worn out from song."

Hope

All during that first summer in Camp Z30-D, the female prisoners smile at one another, silently acknowledging the wonderful things about to happen, even amid the horrors of building their own concentration camp.

When will the first one take place? How will they handle it? Is it possible to nurture fragile little lives in the confines of a bamboo jail?

Several of the women around Hong Nga, 24, are expecting – already pregnant when the summons ordering re-education confinement arrived months earlier.

"How do we nurse?" one wonders.

"Where can we find more food?" questions another.

"What names will we give them?" asks a third.

Despite their swelling stomachs, they dig trenches, raise pigs, plant corn under the harsh sun.

Hong Nga, a captain in the South Vietnamese army who anchored the official evening news, watches them in the quiet twilight, wishing for a child of her own. She offers to take on their heavy chores, carrying water buckets and hauling big loads.

Sometimes she thinks of her own childhood, when, born as Dong Nga Thi Ha, she would sit for hours by the radio or television, listening to her favorite stars, mimicking their speech and aspiring to be a face and a voice for her nation.

As the hot, long summer days grow shorter, the women start to have their babies. Accompanied by guards, they leave the camp overnight and give birth with the help of midwives. They return with their babies the next day.

New mothers are not given extra food, but other inmates readily offer theirs. They are allowed one to two months to nurse, and then they return to the fields either taking their babies with them or leaving them in a makeshift nursery.

Hong Nga, one day, gives up her bed slot to a tiny girl with a head of soft curls. She prepares warm vegetable broths, rocks crying babies back to sleep, changes thin cloth diapers. Sometimes, when there is nothing else, they cover the infants' bottoms with the tattered fabric of their own prisoner's stripes or the leaves of a banana tree.

One day in the spring, a boy falls ill as his mother carries him on her back in the fields. He can't stop vomiting.

"Oh Lord, please don't let him die," the woman wails. The other women start to weep. There is no formula.

Hong Nga's heart thumps wildly. Her chest feels warm and heavy. A devoted Catholic, she prays throughout the night.

The baby recovers the next evening. Hong Nga runs over and kisses his cheeks.

"I treated the children in prison as my own," she says. "The time at Z30-D showed me that I had a mother's unconditional love."

As the years pass, the Camp Z30-D babies grow into toddlers, then young children. Hong Nga feels her life slipping away.

Her husband, a once-strong army captain, has written her, saying he is weak and sick in a jail in the North. One day, Hong Nga hears from relatives that he has heart trouble. She fears he will die before she can have a baby to carry on his name, Ngot Van Le. She aches for someone to sing to. Then she would have a reason to go on living.

Finally, in 1979, Hong Nga is released from Camp Z30-D. She immediately sets out to fulfill her dream of having a family. But she discovers there is nothing left of her old home. First, she sells scraps on the streets of Saigon to keep a roof over her head and her mother's. Then she pawns all her valuables. After nine months of struggling, she scrapes enough together to buy a ticket to the North to see her husband.

At last, she is on the train to Hanoi. The 40-hour trip gives her time to think. She wonders if her husband, Ngot, still has that broad smile and thick, jet-black hair.

In Hanoi, she boards a bus headed into the mountains. She clutches gifts of rice, medicine, dried fish, sugar — and crumpled bills.

Finally, they gaze at one another across a prison table. He can't stop coughing. She fights back tears.

"He looked like a ghost with his sunken eyes, missing teeth and gray hair," she says. "I had to reach out and touch him, to make sure he was still alive."

After five years of separation, they have 15 minutes to talk. A guard stands at their side. Ngot looks into his wife's face, eyes shimmering with tears.

As the visit ends, Hong Nga makes the move she has been thinking about for years. She slips 10,000 dong, the equivalent of 80 cents, into the hands of the man carrying the rifle. He closes his fist. Hong Nga and Ngot will spend the night in a "guest cottage" a few miles from the center of the camp.

The couple shut the door behind them. Hong Nga has carefully timed the trip so she is ovulating. She glances around: dirt floor, bamboo walls, a ceiling of thatched palm fronds. In the middle is a raised wooden platform. No pillows, sheets or blankets.

"I want to have a child," she blurts out.

"Are you crazy?" he asks. "Get your head together. Think of all the reasons not to."

Neighbors will accuse her of infidelity. Even if they believe her story, the baby will bear the stigma of having a prisoner for a father. And just how does she plan to raise a child when she has barely enough money to feed herself?

"Children need two parents," Ngot says. "I could very well die here in prison."

"But that's why we must take this chance. There might be no second chance. Please, don't you remember the dream on our wedding day? We were meant to be a family."

"But what will you do with them when I am gone?"

"I don't know," she replies.

"How can you bear the burden of being an only parent?"

"I don't know. But I don't want to think about that now. I am not changing my mind."

Her husband grows silent. She blows out the kerosene candle. They feel awkward and try to avoid seeing the worry, the pain in each other's faces.

Hong Nga's skin tightens as she feels the cold board. Husband and wife cry. Their bodies shake with nervousness.

"There was no passion," she says, "only prayers for a miracle."

Nine months pass, and Hong Nga gives birth to a baby boy. She names him Khanh. The following year, she returns to the prison. The couple conceive another son, Duc.

"When I look at my boys, I remember the irony of hope being conceived in prison, a hopeless place," Hong Nga says. "It reminds me of a poetry collection titled `Flowers From Hell.'"

Epilogue

In 1993, Hong Nga, her sons — then 11 and 12 — and her newly freed husband immigrate to Orange County through a program for former South Vietnamese military veterans.

She borrows money from friends, buys a sewing machine and sets up business in the dining room of their nearly empty apartment in Garden Grove. A statue of the Virgin Mary looks on as she mends old clothes and cuts patterns for new ones.

But the years in prison continue to take their toll. Her husband, Ngot, grows weaker by the month. Hong Nga holds his thinning, shivering body, whispering words of encouragement through dark nights. Eventually, he collapses from a heart attack and dies in the hospital six months after setting foot on U.S. soil.

"Khanh, Duc and I made a vow at his funeral," Hong Nga says. "We promised that his sons would take his place. They would be living memories to the hope that gave them life right in prison."

Two years ago, Hong Nga saved enough money to start her own business, T&N Super Discount, a variety store in Garden Grove. Almost every week, she visits her husband's remains at Westminster Memorial Cemetery. The glass case with his ashes is graced with yellow lilies and a rosary.

Her sons now are working to fulfill one of their father's dreams: that they graduate from college. Living with their mother and grandmother, they take classes at Orange Coast and Golden West colleges, both pursuing degrees in computer science.

Resistance

"What's going on in there?" the guards scream, pounding furiously. "We demand that you show yourselves!"

Silence. All the doors to Barrack No. 7 are locked - from the inside.

Phat Phu Nghiem paces. "Now," he says to himself. "This is the moment."

He opens his mouth to sing. His honeyed voice draws the men from the farthest bunk. He strums his guitar as the inmates gather, hundreds of them, palms clapping a staccato beat, paying homage to mothers who have lost sons in battle, to soldiers who have fought with all their strength.

The crescendo builds.

Outside, prison officers shout, "Quiet down! Obey, or you will be punished!"

It is the second day of Tet, the Vietnamese new year, and Phat has helped plan this day for months. Nothing, he vows, will stop the rebellion in Camp Z30-D:The inmates will take over the barracks, beat informants and prove their unity.

Phat draws on the inner strength he developed while growing up and studying the Buddhist faith. He would meditate for hours, fast for days and memorize Buddhist teachings.

"Free yourself from the trappings of the world," he would tell himself over and over.

It's 1981, a year since Phat first conceived of the uprising. After a half-decade of being under prison rule, and under the thumb of informant-trustees, Phat grew convinced that the inmates had to strike back, even if it was just to save their dignity.

While his bunkmates slept, Phat would lie on his straw mat, staring into the blackness, searching for a tune, just as he did as a teen-ager when he composed his own music.

"You cannot motivate just with words," he says. "It has to be done with song. A melody, lyrics, the feeling you get when you hear a certain line. It blends together."

Night after night, Phat secretly crafted the phrases that he hoped would move the men to come together, to show the bosses at Camp Z30-D that their captives had not given in to re-education.

"We want to keep the fires of resistance burning," Phat told others. "We must not be weak. We must fight."

Several prison leaders agreed to the plan and assigned certain prisoners to break the legs of the worst informants.

For months, Phat and others quietly shared his ballads. He whispered lines to inmates in the fields as they planted jicama - a sweet root plant - in the stream as they bathed, in the kitchen as they rinsed dishes. The men heard about passion, misery, stolen youth. But some remained unconvinced.

"You were a civil engineer by trade," one reminded him. "What do you know about rebellion?"

"Are you insane?" another asked. "How will we skeletons win over guards with guns?"

"There is no middle ground in this plan. Either we succeed or die," Phat says. "I am prepared to be killed for my actions."

Eventually, the prison command hears that Phat is stirring up something. It transfers him around in what has grown to a sprawling prison complex with thousands of prisoners. But Phat's movement through Camp Z30-D only helps him spread his songs. Slowly - verse by verse - he has hundreds of inmates humming his tunes.

Around 6 p.m. on the appointed day, Phat starts singing in Barrack No. 7. Other prisoners join, singing anti-communist tunes, reciting poetry about their sorrows and hopes, praying for better times. Inmates in several other barracks join the movement.

Phat launches into "Anh Hung Vo Vang Tu," which says heroes never back down - even in the face of defeat.

Then Phat sings out the prearranged signal:

"If one person falls, thousands will rise up."

"If thousands fall, millions will rise up."

Within seconds, the inmates strike. They swing firewood stolen from the kitchen.

"You still want to betray us?" one attacker asks an informant.

"Now," his partner says, "now you get a taste of the torture you put our friends though by ratting us out."

Screams echo off the barrack walls. Guards rush through the prison yard.

Suddenly, an informant manages to open a door. Bloody, he makes a run for it. Two inmates give chase.

Guards grab the inmates and surround Barrack No. 7.

"Free our friends! Give us rights!" the inmates shout from inside.

The chanting lasts through the night and into the third and final day of Tet. "Free our friends! Give us rights!"

The warden calls in reinforcements. They break into the barracks, weed out the protesters and scatter them to different prisons.

The guards throw Phat into solitary confinement for 33 days. He loses 25 pounds. He never again sees or hears from several of the protesters.

"On the surface, it looked like we lost," he recalls. "But I still believe we won because that proved to me my spirit was still alive. I was proud of my inmates because they still had a free mind. And they were willing to fight to keep it."

Epilogue

After eight years in prison, Phat was released and eventually found his way to Orange County . He made a living teaching piano and classical Vietnamese instruments in a small studio attached to his house. He also volunteered at Lien Hoa Temple several days a week, where he co-produced a weekly radio program and was an adviser to the head monk.

But in late December, Phat was convicted of two counts of child molestation involving two of his students. Since then, he's been held in the Orange County Jail, where he awaits sentencing May 18. He faces three to 10 years in prison. The couple haven't figured out how to tell their adopted daughter, who still lives in Vietnam .

His wife plans to sell their Garden Grove home and rent a room nearby. His studio sits unused and locked. Inside, on a special rack, is the guitar he used at Camp Z30-D.

Family

Riding in a rusty bus squished against her mother, Khang Ngoc Quach smells the dry earth on the nearly empty road to Camp Z30-D. In the fields, oxen pull rickety carts over fallow ground that come spring will turn fertile. Strips of flags flutter in the wind.

Khang, 10, is on her way to meet her father. She has not seen him since her third birthday.

In front of the prison's scrawled sign, children chase one another, their feet dusty in flip-flops.

Mother and daughter pass the guards' bungalows. Laundry dries in the heat. Inmates, wearing prison stripes and conical hats, plant corn in the fields.

It is 1982, and strict order is the rule at Camp Z30-D with the fires of Phat Phu Nghiem's rebellion having been snuffed out for a year.

They approach a small building for visitors. Inside are several doors leading to smaller rooms. Khang and her mother enter one. A gaunt man waits inside.

“I have brought someone to see you,” her mother tells the stranger.

She approaches the man, seeing his eyes light up. He turns toward her. Hesitates. Then steps around a small table. He stoops down and reaches to hug her.

She looks up, the man looming over her. She can feel his tears on her forehead, trickling down her soft brow. “Con toi,” he says. “My child.”

The words sound strange — no man has ever called her that.

Lam Ngoc Quach strokes his daughter's hair, then whispers to his wife.

“The pictures you have shown me of her are nothing like seeing her in person.”

“You will fulfill the dreams that I couldn't,” he says to Khang. “You will be my future. Please remember that you must study, and study hard.”

She can only clutch his hand, recalling how she grew up listening to tales about her father, a soldier who still loved her even though he was in prison.

The youngest of four, Khang was told she was her father's favorite. Her birth was the only one he was able to attend, having been on duty when the other children were born. When Khang's head emerged, her father christened her, immediately announcing her name.

Khang was told how Lam doted on his newest child -- even helping to change her diapers, in his view a “revolutionary act.” He fed her strained carrots and scrubbed milk stains from her bib. He scooped up Khang on his shoulders and ran around the house, feeling the energy seep back into his body after a long day on the base, his daughter yelling, “More! More!”

As Khang stands in the cramped visitors room at Camp Z30-D, other memories slowly seep back: The airy, four-bedroom home in an upscale neighborhood of Saigon; her siblings attending private schools, on their way to becoming doctors, lawyers, university professors.

But in 1975, Lam was among the first prisoners shipped to prison, leaving Khang with little more than family portraits. Her favorite picture showed everyone beaming during a beach outing. She is wrapped in her father's arms, her “funny-looking” belly button showing.

The family soon lost its property and moved in with Khang's aunt. Her mother peddled trinkets, bread, bananas — whatever she could. Classmates taunted Khang because her father was in prison. Even the teachers lectured about dads such as Khang's — bad men who needed to learn to treat their country better. But Khang, sensing her mother already was shouldering more than she could bear, didn't talk about being tormented.

As the years drifted by, both mother and child struggled in their own ways — the parent without a shoulder to lean on, the child without a shoulder to cry on.

Now, seven years after the fall of Saigon, Khang must say goodbye to her father once again. After holding one another for less than a half-hour, mother and daughter pass through the gate that marks the entrance to Camp Z30-D, Lam far behind and deep inside.

Epilogue

In 1984, Khang's father is released from Camp Z30-D. Local police order him to record his activities in a journal and review it weekly. Feeling there is little chance for a better life, the family decides to escape.

The three oldest children go first, Lam leading the way through jungle and a maze of winding paths to Thailand. He returns for Khang — risking being thrown back into prison, and walking nearly a week to reach his hometown. Finally, the family is reunited in late 1986 at a refugee camp. Months later, they arrive in Orange County.

As a teen-ager, Khang watches her father learn English, get a driver's license and land a job at a Long Beach catering factory, where he rises from delivery man to quality control supervisor.

“He teaches us by example that we must try to overcome our obstacle,” Khang says. “He doesn't forget what happened in prison. He just moves beyond it.”

As the years pass, Khang's three older siblings finish school, find work, marry and move out. Khang prepares to follow. But in 2000, her mother, 56, dies from liver cancer. Khang decides to stay with her father in their two-story Westminster condo, its entrance lined with peach blossoms.

Khang, 28, and her father, now 59, hang like friends. They are regulars at Costco, where they sometimes treat themselves to a thick T-bone or a New York steak. She isn't keen on action movies, but will sit through one while enjoying Vietnamese fast food with her father on their living room couch.

“All along, Dad has only asked that I give my own children more than what he has given me,” she says. The request reflects the meaning of Khang's name — peace and prosperity.

Love

Thanh Thuy Nguyen eagerly scans the crowd at the bus depot.

Boys hawk herbal drinks. Young women clutch babies. Pedicab drivers hustle fares. And men and women such as Thuy, their bodies shrunken and lives broken, search for a familiar face as they emerge after years behind bars.

“Where is he? Where is he?” Thuy repeats to herself. She is a far different woman than the one who helped build Camp Z30-D in 1975. Her silky hair is gone. Her skin is deeply lined. Her top row of teeth has fallen out.

“I was a sore sight. Every time I smiled, I looked like a hag,” she recalls.

It is February 1988, and most of the political prisoners have been released, to be replaced by common criminals. It's been nine years since Hong Nga was released from Camp Z30-D, found her husband and started her own family, four years since Khang Ngoc Quach's father, Lam, was allowed to leave and resumed raising his children, three years since Trach Duc Nguyen was set free, fell in love and married.

Thuy's weary eyes alight on a thin figure. But when he nears, she sees it is not her husband but his brother -- come to collect the old spy whose life at Camp Z30-D stretched longer than she thought she could possibly bear.

Twelve years, 281 days, nine hours.

At dawn that day, her husband had gone to one bus station, his brother an other. Thuy had no time to notify her family because of the camp's late decision to let her go. But they saw her quoted in a recent newspaper story about re-education prisoners, and knew that public acknowledgement of her existence meant she would be set free in a matter of days. They've been scouring bus stations since.

Thuy carries the sum of her belongings: A blouse sprinkled with flowers. A yellow sweater her children sent to keep her warm. A thick roll of hair she hacked off in prison because there was no soap with which to wash it. A blue warden-issued shirt, stamped “Z30-D” across the back.

At last, husband and wife find one another.

“Thanh Thuy, Thanh Thuy,” her husband, Dung, murmurs over and over, stroking her head.

To celebrate her return, the family heads to a local hu tieu restaurant, serving a special rice-noodle dish laced with roast pork, chicken, shrimp and bean sprouts. Normally, her husband would pay for the meal. But, unemployed since his own release from prison, Dung spent his last few dollars for a ride from the outskirts of town. Thuy's in-laws quietly pick up the bill.

Halfway through the noodles, Thuy's malnourished stomach rebels. She has to put down her chopsticks.

It's a difficult moment for the proud woman who, by age 26, helped run the first-ever women's secret police agency in South Vietnam. She would pose as a communist, befriend enemies, arrest Ho Chi Minh's guerrillas and haul them into headquarters for interrogation. Now she can't keep down her noodles.

The next afternoon, husband and wife set off for home, two hours from the city. Relatives and friends pitch in, collecting 80,000 dong -- about $6 -- to buy the cheapest tickets on a minibus.

During the ride, Dung tries to prepare for what lies ahead.

“We are poor. Very poor. What you will find waiting for you will not be much,” he warns.

She nods, certain it will be much better than what she has endured. They reach the dirt road of her childhood. Thuy looks at her old home. The one-story house sits between two school halls. Wood beetles have gnawed away part of its structure. Mold clings to corners. The patio roof is gone -- taken by thieves. Part of the floor and walls are rotting away.

Thuy opens the door.

“Me, Me, I'm home,” Thuy yells out.

Her mother runs up, halting midway. “Is that really you?” she asks. “Or are my tears blurring my vision?”

Thuy strains to see past her mother, searching for her two developmentally disabled daughters she was forced to leave in the care of their grandmother so long ago.

She sees them in the back, washing dishes. They are 20 and 17, and don't quite grasp what is happening.

The younger one says, “You're our mom? You look so old, as old as Grandma.”

Thuy doesn't know how to respond. Tears roll down her cheeks.

In prison, everybody called her ``Mother Hen,'' the camp leader. She taught inmates how to survive by breaking off cornstalks in secret and chewing them raw. By hiding vegetables under their clothes, then washing them while dunking into a stream to bathe. She was doctor and dentist, pulling teeth with no anesthesia -- just a modified hammer and teaspoon.

At Camp Z30-D, Thuy was praised as wily. Now she's just old.

She knows her children mean no harm and pulls herself together, summoning the same toughness that made her famous as a girl for taking on boys in schoolyard fights.

She kisses the children's cheeks. Their hair.

“Mommy's still young enough to hug you two.”

They trail her as she walks around the house. The altar for worship is gone, as are her beloved antiques. Sold for food. Her closet is bare. Her pants, shirts and dresses? Sold for food. In the kitchen, she lifts the rice bin -- there's barely enough to fill two soda cans. The cupboards have no fly netting. The shelves are empty, save for five bananas.

Thuy turns to her family, learning her son is out, delivering Coke bottles.

“How have you been able to live?”

“Just as you have been able to survive,” Thuy's mother responds.

She gazes at her daughters. They are as tall as she. The hems of their pants hang above bony ankles. The sleeves of their blouses are too short.

It is the eve of the Lunar New Year -- Tet -- the biggest celebration of the year. In the morning, people throughout Vietnam will put on their best clothes and visit neighbors and family, exchange gifts and wish for good health and a year of prosperity.

Thuy weeps. She has missed so many chances to show a mother's love. She turns to her old, white Singer machine and sews through the night, using material from her prison clothes and fabric donated by an uncle. She fashions two cotton pantsuits for the girls, one pink, one green, both sprinkled with flowers.

“My life was wiped out,” she remembers. “But I was convinced I would succeed again. Because if you can outlast prison, you can outlast anything.”

Epilogue

Darkness is beyond her window as Thuy arises, flicking on lights and taking tubs of food from her refrigerator.

There's meat, sliced thin and marinated. Broccoli, carrots, cauliflower mixed in spices. Soon the kitchen comes alive with the sounds of pork sizzling in a wok, taro-root soup burbling, steam rattling the lid of her jumbo rice cooker.

Thuy, now a caterer, sweats through the next three hours, preparing food that her husband will leave on the doorsteps of 20 families' homes. She combs the hair of her younger daughter, 30, to prepare her for school. She packs lunch for her engineer son. All the while, she mourns yet another loss -- her eldest child, 33-year-old Thao, diagnosed with a brain tumor, died after an operation in February.

By 9 a.m., Thuy goes from Santa Ana to Fountain Valley to open her deli, Thien Nga. She works through dinner and heads straight to the supermarket, stocking up on ingredients for the next day's creations.

Twelve hours later, Thuy, 59, is back at her kitchen counter, chopping, dicing, peeling. She sneaks in a bite and falls asleep, bone-tired, near midnight.

Less than five hours later, Thuy will do it all over again. Just as she has since her arrival in America in 1992.

“Once I fainted from exhaustion,” she says. “My son had to remind me that I'm no longer in prison.”

Legacies

Hung Huy Nguyen has a simple, final thought about his 13 years in prison.

“You must not forget, because then you can make the future better,” he says. “If you remember us, our souls will not die in vain.”

When he says this, he speaks to his children and grandchildren. But, just as important, he delivers this message to anyone who will listen. Hung, the former colonel, still honors his parents' admonition: “Live to serve others.”

Dozens of former prisoners interviewed for this project echoed Hung's words, saying that if there is any good to come out of Vietnam's re-education effort, it is that people learn never to repeat the intolerance that allowed the prisons to be built.

Thanh Thuy Nguyen, the former major general, says, “I just want people to remember that I made it. I didn't give up on hope.”

Resistance, family, hope, the former prisoners said, were the values that helped them make it through each day. But respect for others -- and forgiveness -- were the lessons that allowed them to endure and carve new lives in a new world.

Trach Duc Nguyen, for example, couldn't push thoughts of revenge out of his mind while in jail. Yet during his escape, the poet released a boy who would later turn him in.

“I couldn't kill another human being,” Trach says. “That would make me just as evil as my captors. Then I wouldn't have learned anything from Camp Z30-D.”

Hong Nga, who conceived her two sons in her husband's prison, says, ``Violence only brings horror and agony.

“It is love that heals and unites.”

Discovering How to Overcome Adversity

Unsung heroes all around us have overcome seemingly insurmountable difficulties. Here are some ways to connect:

- At Home — Ask your parents, grandparents, children or other relatives about how they faced special challenges. Talk to them about the struggles of growing up, military service, immigration, persecution or other experiences. Ask about special lessons they learned.

- Elsewhere — Talk to teachers, friends, people of different ethnic or religious groups about tolerance and intolerance.

- Interviewing tips --— These issues can be extremely emotional, so you will need to approach them with patience and sensitivity.

- Try a variety of formats, from casual chats at the park to formal interviews, whatever seems to work best.

- Talk more than once and for more than an hour. You'll discover that new details come out the second time around, especially when dealing with long-suppressed memories.

- Ask follow-up questions, what helped them, lessons they learned.

- Keep a record — What you learn likely will be valued in your family for generations to come, possibly by others as well.

- Document the experience on video or cassette tape.

- Record your observations in a journal and share it with those you interviewed.

- Turn your findings into a school project.

OTHER RESOURCES

- Get more information online at

www.amnesty.org

www.vietworld.com

www.hrw.org

www.state.gov

- Suggested books: "Diary of Anne Frank," Michael Herr's "Dispatches," Lu Van Thanh's "The Inviting Call of Wandering Souls," Nghia M. Vo's "The Pink Lotus," Bao Ninh's "The Sorrows of War," Stanley Karnow's "Vietnam: A History," W. Courtland Robinson's "Terms of Refuge: The Indochinese Exodus & the International Response."

- Suggested videos/DVDs: Steven Spielberg's "Schindler's List" and "Saving Private Ryan," Oliver Stone's "Heaven and Earth" and "Born on the Fourth of July," Roland Joffe's "The Killing Fields."

FIELD TRIPS

- Visit the heart of Little Saigon, along Bolsa Avenue between Ward Street and Newland Avenue in Westminster, taking in the culture, sampling the food, touring the shops. You can do the same for other ethnic enclaves, such as Little Gaza in Anaheim or the Korean Commercial District in Garden Grove.

- Go through the Simon Wiesenthal Center and Museum of Tolerance, 9786 W. Pico Blvd., Los Angeles, (310) 553-8403.

- Browse the materials at the Southeast Asian Archive inside the main library of the University of California, Irvine. (949) 824-4968.

TO ORDER REPRINTS

- $2.00 each (includes tax and mailing). Send a check or money order to InfoStore - Camp C30-D, 625 N. Grand Ave., Santa Ana, CA 92701. To order by credit card call the InfoStore at (714) 796-6077.

MORE ON THE WEB

Go to www.ocregister.com for:

- A complete online version of Camp Z30-D: The Survivors.

- Additional photos.

- Sound clips from interviews with the former prisoners.

- Links to related Web sites

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

- Give us your comments, exchange ideas with writers Anh Do and Hieu Tran Phan or photographer Eugene Garcia, submit questions for the former inmates of Camp Z30-D and share your own experiences. Go to http://dialog.ocregister.com, register and join the discussion groups on Vietnam’s re-education prisons.

Camp Z30-D: The Survivors

IN HONOR OF THE TENS OF THOUSANDS OF MEN AND WOMEN WHO DIED IN VIETNAM'S RE-EDUCATION CAMPS

At least 165,000 people perished in Vietnam's re-education camps after the fall of Saigon in 1975, according to published research in the United States and Europe. The Hanoi government declines comment. Following is a partial list documented by the Vietnam Human Rights Watch, a privately funded organization.

Sgt. Abdul Hamide, Tan Lap Re-education Camp (Vinh Phu), died in 1979. Ali Hung, Navy Seals, executed. Capt. Anh Dong, Paratrooper Camp 5, Ly Ba So Re-education Camp (Thanh Hoa), died in detention. 1st Lt. Au Duong Diep, Z30-A Re-education Camp, died from hunger strike in 1980. Capt. Au Duong Minh, national police, Z20-A Re-education Camp, died from hunger strike in 1979. Lt. Col. Bach Van Hien, air traffic control at Tan Son Nhat Airport, died of untreated illness at unknown location in North Vietnam. 2nd Lt. Bao Thanh, 1st Supply Battalion, Long Giao Re-education Camp (Dong Nai), executed at labor site in December 1978. Bao Trong, deputy commander for national police, Phan Dang Luu Detention Center, died after repeated torture. Lt. Bon (family name unknown), national police, Re-education Camp 4 (Yen Bai), died in detention. 2nd Lt. Bui Bang Bim, Thanh Hoa Re-education Camp, hanged himself. Lt. Col. Bui Hien Ton, national police, Thanh Hoa Re-education Camp, died in 1979. Lt. Col. Bui Hong Viet, military police, died of untreated illness. Cpl. Bui Huu Kiet, Nha Do Re-education Camp (Song Be), died of malnutrition and overwork on April 10, 1977. Bui Huu Kiet, Nha Do Re-education Camp, tortured to death in 1977. Bui Huu Tinh, Nam Ha Re-education Camp, died under interrogation in 1979. Capt. Bui Kim Dinh, Office of Military Security, shot by a camp guard, July 1975. Sgt. Bui Long Tim, Binh Dinh National Police Command, Z30-A Re-education Camp, died of pneumonia in August 1982. Bui Luong, head of a labor union, Xuan Phuoc Re-education Camp, died in 1984. Bui Ngoc Phuong, presidential candidate, Xuan Phuong Re-education Camp (Phu Khanh), died in 1983. Maj. Bui Nguyen Nghia, infantry, Xuan Phuoc Re-education Camp, died in 1980. 1st Lt. Bui Quoc Dong, Counter Intelligence Bureau, Ha Tay Re-education Camp, died of suspected poison injection in March 1982. Maj. Bui Van Ba, Vinh Liem Military Training Center, died in 1975. 1st Lt. Bui Van Bai, Vung Tau National Police Headquarters, Nam Ha A Re-education Camp, died in 1979. Maj. Bui Van Lang, national police, died during transfer from North to South Vietnam. Brig. Gen. Bui Van Nhu, national police, Nam Ha Re-education Camp, died in 1983. Col. Bui Van Sam, 33rd Ranger Brigade, Z30-C Re-education Camp, died in 1983. Rev. Bui Van Thay, Catholic priest, My Tho K3 Re-education Camp (Vinh Phu), died in early 1980. Capt. Cam (family name unknown), artillery division, died at unknown location in North Vietnam. Lt. Col. Can (family name unknown), military choir, Son La Re-education Camp, died of liver disease in 1976. Maj. Cang Van Nhieu, Suoi Mau Re-education Camp, died of diarrhea in 1979. Capt. Cao Phuoc An, artillery unit in Vinh Long Province, Tan Hiep Re-education Camp, died in 1978. Capt. Cao Quang Chon, prosecutor, K2 Re-education Camp (Thanh Phong, Thanh Hoa), disappeared after interrogation. Lt. Col. Cao Tan Hap, governor of Vinh Binh Province, Camp No. 6 (Nghe Tinh), died in 1978. Lt. Col. Cao Trieu Phat, paratrooper, died at unknown location in North Vietnam. Capt. Cao Xuan Huong, Lam Dong Re-education Camp, died in 1982. Judge Chau Tu Phat, Saigon District Court, U Minh Ha Re-education Camp, died under interrogation. Capt. Chieu (family name unknown), military police, An Duong Re-education Camp, died of illness in 1976. Capt. Chu Minh Loc, deputy chief for military security in Tuyen Duc Province, Hoang Lien Son Re-education Camp, beaten to death after failed escape. Col. Chung Van Bong, governor of My Tho Province, detention center in Bien Hoa, died of illness. Capt. Chuong (family name unknown), T3 Re-education Camp (Hoang Lien Son), drowned along with seven others. Capt. Cu (family name unknown), military police, Hoang Lien Son Re-education Camp, drowned at Thac Ba Falls during hard labor on Sept. 28, 1976. Cu Minh Kien, chief of Can Dang Hamlet, executed at Chuong Binh Le School. Capt. Cuu (family name unknown), Vuon Dao Re-education Camp (Cai Lay), died in 1979. Capt. Dam Dinh Loan, military academy, Van Ban Labor Camp No. 4, died in 1977 of unknown cause. Lt. Col. Dam Minh Viem, engineer corps, Suoi Mau Re-education Camp, committed suicide in February 1976. Col. Dam Trung Moc, police academy, Ha Tay Re-education Camp, died in 1982. Capt. Dan (family name unknown), retired, executed at Binh Minh Camp. Capt. Dan (family name unknown), Nam Ha Re-education Camp, died of hypothermia during winter of 1978. Maj. Dang (family name unknown), ordnance officer, Gia Trung Re-education Camp, died in 1979. Lt. Col. Dang Binh Minh, helicopter pilot for the president, Yen Bay Re-education Camp, died in 1978 or 1979. Officer Dang Dinh Tung, Trang Lon Re-education Camp (Tay Ninh), committed suicide with an overdose of chloroquine. Capt. Dang Duc Chau, Hoang Lien Son Re-education Camp; camp authorities said he drowned on July 8, 1978. Commander Dang Huu Than, council member of Khanh Hoa, A-30 Re-education Camp, executed after failed escape. Capt. Dang Minh Kinh, 9th Infantry Division, 9A Re-education Camp (Thanh Hoa), died in September 1981. Notable Dang Ngoc Liem, Cao Dai Religious Sect, executed in Tay Ninh. Dang Van Kien, national police, Quang Ngai Province, forced into a well with 11 other political prisoners and killed with a grenade explosion in 1975 in Tu Thinh, Quang Ngai. Col. Dang Van Thanh, regiment commander of 21st Infantry Division, Chuong Trau Re-education Camp (Yen Bai), died in 1976 after failed escape. Congressman Dang Van Tiep, House of Representatives, Thanh Hoa Re-education Camp, beaten to death during solitary confinement in 1982. Master Sgt. Dang Xuan Hoan, national police, Phu Huu Detention Camp (Binh Duong), taken into the woods by camp guards and executed on May 15, 1975, along with 12 other political prisoners. Lt. Col. Dang Xuan Nong, ordnance officer, Khanh Hoa Prison, died in detention. Capt. Danh (family name unknown), medical assistant in 4th Military Zone, Hoang Lien Son Re-education Camp, died of diarrhea. Dao Cong Hoang, teacher of French literature at Chu Van An High School, Song Cai Re-education Camp, died of malnutrition and exhaustion in March 1981. Lt. Col. Dao Ngoc Thanh, chief of staff's office, died at unknown location. Dao Quy Binh, died from a hunger strike. 1st Lt. Dao Thanh Ta, national police, Z30-D Re-education Camp, died from lack of medication for asthma in late 1978. Maj. Dau Quang Duong, Cay Mai Intelligence Unit Camp C, Phu Son 4 (Bac Thai), died in detention. Deo Van Ngay, civil servant, executed after failed escape in 1978. Maj. Diep Van Sa, chief of Military Security Section, Vinh Quang Re-education Camp, died of tuberculosis in 1980. Officer Dieu (family name unknown), An Duong Re-education Camp, died of illness in 1976. Capt. Dieu Chinh Thang, Ham Tri Re-education Camp, last seen alive in 1976 by fellow inmates. Congressman Dinh On, House of Representatives, Kim Son Re-education Camp (Binh Dinh), died from beating. 1st Lt. Dinh Quang Ha, Tan Bien Re-education Camp, executed on Dec. 15, 1977, after failed escape. Family denied permission for proper burial. Dinh Reu, ranger for Border Patrol Battalion 69, Son Nhom Re-education Camp, died of fever. Dinh Van Bien, Vietnam's Nationalist Party, Tien Lanh Re-education Camp (Quang Nam), died in detention. Lt. Col. Dinh Van Tan, department of defense, Yen Bay Re-education Camp, died of food poisoning. Maj. Do Dinh Ky, Long Giao Re-education Camp (Long Khanh), died in 1975. Officer Do Huu Tai, Xuyen Moc Re-education Camp, executed on May 26, 1980, after failed escape. Maj. Do Huu Tuoc, Dalat Military Cadet Academy, Lang Son Re-education Camp, died in detention. Maj. Do Kien Nau, national police, Ha Tay Re-education Camp, died in 1977. Lt. Col. Do Ngoc Anh, navy, accidental death during forced labor in 1976. 1st Lt. Do Rang Dong, paratrooper, Long Khanh Re-education Camp, killed in 1976 by explosion while clearing land mines. Do Van Diem, Dong Nai Re-education Camp, died of malaria on April 3, 1979. Capt. Do Van Muoi, Phoenix Program, executed after failed escape. Capt. Do Van Nhi, Ly Ba So Re-educa tion Camp (Thanh Hoa), died in detention. Capt. Do Van Toan, Infantry Camp K1, died in 1982. Sgt. Do Van Tuong, Ninh Thuan National Police Command, Song Cai Re-education Camp, died from dengue fever in November 1975. Col. Do Xuan Sinh, deputy director of Military Supplies Office, Hoang Lien Son Re-education Camp, died in detention. Col. Doan Boi Tran, deputy chief of staff for political warfare, Z30-C Re-education Camp, died upon release due to illnesses contracted in detention. Maj. Doan Huu Tu, Nam Ha Re-education Camp, died during interrogation. Lt. Col. Doan Minh Viem, engineer corps, Suoi Mau Re-education Camp (Bien Hoa), committed suicide. Doan Quang Chau, Rural Pacification Program, K20 Re-education Camp (Ben Tre), died on Dec. 15, 1978, along with 16 inmates. Maj. Doan The Don, Office of the Military Inspector General, Thanh Xuong Re-education Camp (Thanh Hoa), died in detention. 1st Lt. Doan Tu Bang, Long Khanh Re-education Camp, killed by explosion while clearing land mines. Lt. Col. Doan Van Anh, 4th Military Zone, Yen Bai Re-education Camp, died from exhaustion. Doan Van Chau, Rural Pacification Program, executed. Maj. General Doan Van Quang, commander of special forces, Ha Tay Re-education Camp, died in 1984. Officer Doan Van Xuong, Military Cadet Academy Camp T6, Nghe Tinh Re-education Camp, beaten to death after failed escape in December 1980. Lt. Col. Doan Viet Thuyen, Thu Duc Military Academy, Z30-D Re-education Camp, died on April 29, 1987. Lt. Col. Doan Xuan Viem, Muong Khai Re-education Camp (Son La), died in detention. Lt. Col. Don (family name unknown), mayor, executed at the soccer field in Bac Lieu on June 1975. Maj. Dot (family name unknown), Soc Trang Militia Unit, executed in Soc Trang in 1975. Maj. Duc (family name unknown), Suoi Mau Re-education Camp (Bien Hoa), died of diarrhea. 2nd Lt. Duc (family name unknown), national police's soccer team, Re-education Camp No. 4 (Yen Bai), died in detention. 2nd Lt. Duc (family name unknown), Air Force, Ka Tum Re-education Camp (Tay Ninh), died in 1978. Maj. Duong (family name unknown), military security unit, Thanh Phong Re-education Camp, died from untreated appendicitis in 1982. Lt. Col. Duong (family name unknown), national police, executed. Capt. Duong (family name unknown), military doctor, 2nd Infantry Division, T4-LT2 Re-education Camp (Son La), beaten to death after failed escape in February 1977. Duong Duc Thuy, Ministry of Justice, Ha Tay Re-education Camp, died in 1978. 1st Lt. Duong Hung Cuong, writer, Xuan Phuoc Re-education Camp, died in solitary confinement. Duong Mai, Tien Lanh Re-education Camp, executed in 1980 after failed escape. Capt. Duong Ngoc Lam, Vinh Phu Re-education Camp, died in detention. Col. Duong Phun Sang, deputy commander of 5th Infantry Division, Hoang Lien Son Re-education Camp, died in 1977. Pvt. Duong Thu, Xuan Loc Re-education Camp, executed on Dec. 15, 1975, after failed escape. Ga (family name unknown), communications officer, Son Cao Re-education Camp, died of dengue fever in 1975. Col. Giam (family name unknown), An Duong Re-education Camp (Bien Hoa), died of tuberculosis in 1976. 1st Lt. Giang (family name unknown), military doctor, Ai Tu Re-education Camp, died in detention. Rev. Giu-se Dinh Nam Hung, Catholic priest, Vinh Quang Re-education Camp, died from mine explosion in 1980, along with some 60 inmates. Lt. Col. Ha Hau Sinh, Air Force, Tan Lap Re-education Camp, died from illness in 1980. Capt. Ha Hong, national police in Da Nang province, An Diem Re-education Camp, died in detention. Lt. Col. Ha Huu Hoi, commanding officer from Mobilization Center No. 3, died in north Vietnam. 1st Lt. Ha Minh Tanh, Trang Lon Re-education Camp, executed for insubordination in 1979. 1st Lt. Ha Thuc Long, 3rd Regiment -- 1st Division, Ky Son Re-education Camp, executed in 1977 for criticizing camp authorities. Lt. Col. Ha Thuc Ung, company leader for militia forces, Phu Yen Re-education Camp, killed after failed escape. Capt. Ha Van Kham, Song Tranh Re-education Camp, executed. Capt. Ha Van Kinh, chairman of Kien Hoa Provincial Council, Ben Tre Detention Center, executed with 11 fellow inmates on Dec. 25, 1977. Capt. Hao (family name unknown), Thanh Phong Re-education Camp, died in 1981. 1st Lt. Hau (family name unknown), navy, Ka Tum Re-education Camp, tortured and executed after failed escape in 1977. Lt. Col. Hau Cam Pau, inspector general of Long Khanh province, Nam Ha A Re-education Camp, died in 1984. Lt. Col. Hien (family name unknown), Vinh Phu Re-education Camp, died Jan. 15, 1980. Lt. Col. Hien (family name unknown), artillery, Gia Trung Re-education Camp, died in 1980. Capt. Hien (family name unknown), An Duong Re-education Camp (Bien Hoa), died in solitary confinement in 1976 for letting the guards' pigs under his charge die. Hien (family name unknown), Chi Hoa Central Prison, killed in 1981 at Thu Duc execution ground. Lt. Col. Hieu (family name unknown), chief of staff's office, T4-LT2 Re-education Camp (Son La), died from diarrhea in December 1976. Councilman Hieu (family name unknown), Kien Hoa Provincial Council, executed at Ben Tre in 1981. Sgt. Ho A Ung, member of armed resistance, Nam Ha A Re-education Camp, died in 1981. Maj. Ho Ba Dong, Phan Thiet Military Sub-sector, Xuan Loc Re-education Camp, died in 1982. Maj. Ho Dac Cua, 23rd Infantry Division, executed after failed escape. Maj. Ho Dac Dat, communications officer, Bu Gia Map Re-education Camp, died of malaria. Maj. Ho Duc Sung, 3rd Bureau -- 1st Army Corps, Tan Lap Re-education Camp (Vinh Phu), died in 1986. Col. Ho Duc Trung, Member of House of Representatives, Hoang Lien Son Re-education Camp, died in 1978. Col. Ho Hong Nam, Dalat Military Academy, died in 1985 upon release due to illnesses contracted in detention. Ho Huu Hia, Cao Dai religious sect, executed in Tay Ninh. Ho Huu Tuong, scholar, Long Khanh Re-education Camp, died of illness. 2nd Lt. Ho Khac Trung, died at unknown location. Maj. Ho Minh, military court of Da Nang Camp No. 1, Tien Lanh Re-education Camp, died in 1980. Col. Ho Ngoc Can, governor of Chuong Thien Province, executed in October 1975. Ho Quang Vong, Thanh Phong Re-education Camp, died during interrogation in 1978. Capt. Ho Thuc Ha, 18th Tank Division, Hoang Lien Son Re-education Camp, died in 1978. Maj. Ho Van Doi, Hoa Hao Buddhist Militia Unit 40, Kinh Ong Co Labor Camp (An Giang), died in de tention. Councilman Ho Van Ngan, chairman of Trung An Council, executed in 1975. Lt. Col. Hoach (family name unknown), chief of staff's office, died from illness. Hoang Ba Lac, Thanh Phong Re-education Camp, died during interrogation in 1978 or 1979. Capt. Hoang Dinh Ri, Ky Son Re-education Camp, died in December 1975. Hoang Kim Qui, businessman, Z30-C Re-education Camp, died from diarrhea. 1st Lt. Hoang Loc Bui, Gia Phuc Re-education Camp (Phuoc Long), executed in 1979 for expressing ``reactionary'' political opinions. 2nd Lt. Hoang Quang Hua, national police, Binh Dai Re-education Camp (Kien Hoa), died from diarrhea. Rev. Hoang Quynh, Catholic priest, Phan Dang Luu Interrogation Camp, died in solitary confinement in 1975. Maj. Hoang Tam, Hoc Mon Re-education Camp, died in 1976. Capt. Hoang Van Chinh, Ham Tri Re-education Camp (Phan Thiet), executed on Aug. 25, 1977, after failed escape. Maj. Hoang Van Dang, provincial chief of People's Self-defense Force, Huy Khiem Re-education Camp (Binh Thuan), died in November 1988. Sen. Hoang Xuan Tuu, senate, Nam Ha A Re-education Camp, died in 1980. 2nd Lt. Hong (family name unknown), Yen Bai Re-education Cam, died in 1976. Lt. Col. Hong (family name unknown), Vinh Phu Re-education Camp, died in detention. Rev. Hong (family name unknown), pastor of Tra Vinh Catholic congregation, Ben Gia Prison (Tra Vinh), died in 1985. Maj. Hong (family name unknown), F5 pilot, Nghe Tinh Re-education Camp, died in 1980. Maj. Hop (family name unknown), 2nd Marine Battalion, Nghia Lo Re-education Camp, died in 1978. Hu Y Chief, Vinh Xuong Fort, died upon release due to illnesses contracted in detention. 2nd Lt. Hua Khoi, national police headquarters for Da Nang Province, An Diem Re-education Camp, died in detention. Lt. Col. Hung (family name unknown), ordnance officer, Muong Thai Re-education Camp (So La), died in 1977. 2nd Lt. Hung (family name unknown), chief of staff's office, Gia Rai Re-education Camp, died in solitary confinement. Lt. Col. Hung Van Thanh, marine, Gia Rai Re-education Camp (Xuan Loc), committed suicide. Huy Van, editor of Tien Tuyen Newspaper, Camp K4 (Vinh Phu), died in detention. Huynh Chin, Popular Forces 49th Platoon, Phu Cat Phu Cat Prison, executed with six fellow inmates on May 1, 1975. Huynh Chuong, Nuoc Nhoc Re-education Camp (Nghia Binh), beaten to death in 1979. Col. Huynh Huu Ban, F5 Chief of Staff's office, Cay Khe Re-education Camp, died in 1977. Maj. Huynh Ke Thu, air force, Camp 14/LT1 (Yen Bai), died in 1976. Col. Huynh Ngoc Lang, military police, Ba Sao Re-education Camp, died in 1982. Lt. Col. Huynh Nhu Xuan, Military Cadet Academy, died in North Vietnam. Huynh Thanh Khiet, Cao Dai religious sect, executed in Tay Ninh. 1st Lt. Huynh Thuat, infantry, Nong Truong Thong Nhat Re-education Camp, executed on June 7, 1977. Lt. Col. Huynh Van Kien, Hoang Lien Son Re-education Camp, died in detention. Congressman Huynh Van Lau, House of Representatives, Chau Doc Prison, executed on Aug. 24, 1975. Capt. Huynh Van Luc, Phu Khanh Re-education Camp, shot dead when he couldn't meet labor quota because of injured hand. Huynh Van Quan, Kinh Lang Thu 7 Re-education Camp, shot dead during escape attempt on June 7, 1977. Huynh Van Sang, Cham leader, Xuan Phuoc Re-education Camp, died in 1986. Capt. Huynh Van Tho, national police -- 6th District, Phong Quang Re-education Camp (Lao Cai), died in 1978. Maj. Huynh Van Tho, artillery, Hoc Mon Re-education Camp, died in detention. Capt. Huynh Xuan Con, Trang Lon Prison (Cay Cay), executed after failed escape. Lt. Col. Ke (family name unknown), Hoang Lien Son Re-education Camp, died in detention. Dr. Kha (family name unknown), military doctor at Bien Hoa Mental Clinic, killed by a grenade Aug. 31, 1979. Kha Tu Giao, Long Giao Re-education Camp, died from hunger strike in 1977. Lt. Col. Khoa (family name unknown), Nam Ha C Re-education Camp, died of a brain hemorrhage. Capt. Khoan (family name unknown), Vinh Loi Military Sub-sector, Bac Lieu Temporary Detention Camp, committed suicide in June 1975. Le Van Duyet, armed resistance movement, executed for anti-government activities. Lt. Col. Khong Van Tuyen, communications officer, Phu Son Camp No. 4 (Bac Thai), died in detention. Khuc Thua Van, member of Vietnam's Nationalist Party, Xuan Phuoc Re-education Camp, died in 1984. Lt. Col. Kiet (family name unknown), Company 776, Yen Bai Re-education Camp, died during winter 1977. Kieu Ngoc Thuan, Quang Tin Military Subsector, No. 1 Re-education Camp, died of malaria in May 1975. Venerable Kim Sang, Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam, Camp T82, killed in detention in 1982. 1st Lt. Lam Huu Hiep, navy, executed on June 17, 1981, after failed escape. Sgt. Lam Michel, national police, executed in 1975 in Binh Duong. Capt. Lam Quang Vinh, platoon leader -- intelligence unit, Son La Re-education Camp, died in 1978. 1st Lt. Lam Si Phuoc, national police -- bureau of My Trinh Village, Gia Trung Re-education Camp (Pleiku), died of malaria in October 1977. Lt. Col. Lam Thanh Gia, national police, executed in 1975 in Binh Duong. Maj. General Lam Thanh Nguyen (a.k.a. Hai Ngoa), Hoa Hao Buddhist, Armed Forces Detention Center in Chau Doc, died in solitary confinement. Lt. Col. Lam Van Trieu, engineer corps, Vinh Phu Re-education Camp, died in detention. 2nd Lt. Lan (unknown family name), Ky Son Re-education Camp, died in 1977. Le Canh Thanh, national police -- Cat Hiep Hamlet, Phu Cat Prison (Binh Dinh), executed in 1975. Maj. Le Canh Trong, engineers corps, Hue Central Prison, died in detention. Lt. Col. Le Chon Tinh, Hoa Hao Buddhist Militia Forces, executed in 1975 in Chau Doc. Le Cong Tam, deputy chairman of An Giang Provincial Assembly, Kinh 7 Ngan Re-education Camp, died in detention. Capt. Le Cong Thinh, military transport, Long Khanh Re-education Camp, executed in June 1977 after failed escape. Maj. Le Danh Chap, chief of staff's office, Xuan Phuoc Re-education Camp, died on July 3, 1984. Lt. Le Dinh Phon, navy, Giao Long Re-education camp, reportedly committed suicide with drug overdose. Le Du, leader -- Popular Forces 26th Platoon, Phu Cat Prison (Binh Dinh), executed in 1975. Capt. Le Duc Thinh, military intelligence officer, Long Giao Re-education Camp, executed on April 14, 1976. Le Duy Trinh, Open Arms Program, Song Be Re-education Camp, died in detention. Capt. Le Duyen Ngau, Hoang Lien Son Re-education Camp, beaten to death after failed escape. Sgt. Le Huu Vinh, special unit -- Binh Dinh National Police Command, Z30-A Re-education Camp, died of dengue fever in June 1982. 2nd Lt. Le Khac Tuong, leader -- anti-aircraft unit, Suoi Mau Re-education Camp (Bien Hoa), died of a stroke in 1975. Col. Le Minh Luan, air force, Cay Khe Re-education Camp (Yen Bai), died in 1977. Maj. Le Ngoc An, mayor -- An Nhon military sub-sector, Vinh Phu Re-education Camp, died of malnutrition in August 1979. Col. Le Ngoc Day, Quang Trung Infantry Training Center, Xuan Loc A Re-education Camp, died of a stroke in 1986. Officer Le Ngoc Thua, Kinh 5 Re-education Camp, died in detention. 2nd Lt. Le Phong Quang, political warfare department, A30 Re-education Camp (Phu Yen), drowned during forced labor in 1980. Lt. Col. Le Phuoc Mai, Civil Engineers Corps., died at unknown location. Le Quang Lac, intelligence officer, Thanh Hoa Re-education Camp, died in 1980. Le Quang Minh, A20 Re-education Camp, died in detention. Le Quang The, social affairs officer -- Quang Tri province, Hoan Cat Re-education Camp, died from an ammunition .... .

Meet the Team

David Whiting

Editor

Marcia Prouse

Photo editor

Chris Boucly

Graphics editor

Kris Viesselman

Art director

Anh Do, Hieu Tran Phan

Writers

Eugene Garcia

Photographer

Joelle Beckett

Designer

Lewis Leung

Designer

Scott Brown

Artist

Haeyoun Park

Graphics reporter

Dan Bates

Copy editor

Paul Ybarrondo

Copy editor

Rick Hearn

Imaging

2002 Dart Award Judges

PRELIMINARY JUDGES:

Garry Boulden is the supervisor of Crime Survivor Services, a unit of the Seattle Police Department that serves victims of person-to-person felony crimes. Boulden worked for five years as an advocate in the Mayor's Office for Senior Citizens and as the senior specialist advocate for the police department for seven years. He is a member of Seattle's Domestic Violence Council, the Domestic Violence Criminal Justice Committee, POET (Protecting Our Elderly Together) Group, and other victim-services committees. Boulden holds a B.A. in philosophy, an M.A. in theology (ethics), and is a licensed Washington state mental health counselor.

Susan Gilmore has been a reporter at the Seattle Times since 1979. Currently a general assignment reporter, she has also covered City Hall, the environment, fisheries, politics (including a U.S. Senate race), new features, demographics and census, and she wrote for Pacific Magazine. In 1992 Gilmore was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for stories involving allegations of sexual misconduct by former U.S. Senator Brock Adams; these stories also received the Worth Bingham Prize for investigative reporting, the Associated Press Managing Editors Public Service Award, and the Goldsmith Prize. Before joining the Seattle Times, Gilmore was a reporter at the Juneau Empire and the Fairbanks News Miner.