Brain Wars: How the Military is Failing its Wounded

This comprehensive multimedia investigation delves into the ramifications of the signature wound of today’s wars: traumatic brain injury (TBI). Originally published by ProPublica and NPR in 2010.

Brain Injuries Remain undiagnosed in Thousands of Soldiers

WASHINGTON, D.C.--The military medical system is failing to diagnose brain injuries in troops who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, many of whom receive little or no treatment for lingering health problems, an investigation by ProPublica and NPR has found.

So-called mild traumatic brain injury has been called one of the wars' signature wounds. Shock waves from roadside bombs can ripple through soldiers' brains, causing damage that sometimes leaves no visible scars but may cause lasting mental and physical harm.

Officially, military figures say about 115,000 troops have suffered mild traumatic brain injuries since the wars began. But top Army officials acknowledged in interviews that those statistics likely understate the true toll. Tens of thousands of troops with such wounds have gone uncounted, according to unpublished military research obtained by ProPublica and NPR.

"When someone's missing a limb, you can see that," said Sgt. William Fraas, a Bronze Star recipient who survived several roadside blasts in Iraq. He can no longer drive, or remember simple lists of jobs to do around the house. "When someone has a brain injury, you can't see it, but it's still serious."

In 2007, under enormous public pressure, military leaders pledged to fix problems in diagnosing and treating brain injuries. Yet despite the hundreds of millions of dollars pumped into the effort since then, critical parts of this promise remain unfulfilled.

Over four months, we examined government records, previously undisclosed studies, and private correspondence between senior medical officials. We conducted interviews with scores of soldiers, experts and military leaders.

Among our findings:

- From the battlefield to the home front, the military's doctors and screening systems routinely miss brain trauma in soldiers. One of its tests fails to catch as many as 40 percent of concussions, a recent unpublished study concluded. A second exam, on which the Pentagon has spent millions, yields results that top medical officials call about as reliable as a coin flip.

- Even when military doctors diagnose head injuries, that information often doesn't make it into soldiers' permanent medical files. Handheld medical devices designed to transmit data have failed in the austere terrain of the war zones. Paper records from Iraq and Afghanistan have been lost, burned or abandoned in warehouses, officials say, when no one knew where to ship them.

- Without diagnosis and official documentation, soldiers with head wounds have had to battle for appropriate treatment. Some received psychotropic drugs instead of rehabilitative therapy that could help retrain their brains. Others say they have received no treatment at all, or have been branded as malingerers.

In the civilian world, there is growing consensus about the danger of ignoring head trauma: Athletes and car accident victims are routinely tested for brain injuries and are restricted from activities that could result in further blows to the head.

But the military continues to overlook similarly wounded soldiers, a reflection of ambivalence about these wounds at the highest levels, our reporting shows. Some senior Army medical officers remain skeptical that mild traumatic brain injuries are responsible for soldiers' troubles with memory, concentration and mental focus.

Civilian research shows that an estimated 5 percent to 15 percent of people with mild traumatic brain injury have persistent difficulty with such cognitive problems.

"It's obvious that we are significantly underestimating and underreporting the true burden of traumatic brain injury," said Maj. Remington Nevin, an Army epidemiologist who served in Afghanistan and has worked to improve documentation of TBIs and other brain injuries. "This is an issue which is causing real harm. And the senior levels of leadership that should be responsible for this issue either don't care, can't understand the problem due to lack of experience, or are so disengaged that they haven't fixed it."

When Lt. Gen. Eric Schoomaker, the Army's most senior medical officer, learned that NPR and ProPublica were asking questions about the military's handling of traumatic brain injuries, he initially instructed local medical commanders not to speak to us.

"We have some obvious vulnerabilities here as we have worked to better understand the nature of our soldiers' injuries and to manage them in a standardized fashion," he wrote in an e-mail sent to bases across the country. "I do not want any more interviews at a local level."

When confronted with the findings later, however, he acknowledged shortcomings in the military's diagnosing and documenting of head traumas.

"We still have a big problem and I readily admit it," said Schoomaker, the Army's surgeon general. "That is a black hole of information that we need to have closed."

Brig. Gen. Loree Sutton, who oversees brain injury issues for the Pentagon, said the military had made great strides in improving attitudes towards the detection and treatment of traumatic brain injury.

The military is considering implementing a new policy to mandate the temporary removal from the battlefield of soldiers exposed to nearby blasts. Later this year, the Pentagon expects to open a cutting-edge center for brain and psychological injuries, which will treat about 500 soldiers annually.

"This journey of cultural transformation, it is a journey not for the faint of heart," Sutton said. "At the end of our journeys, at the end of our travels, what we must ensure is, we must ensure that we have consistent standards of excellence across the board. Are we there yet? Of course we're not there yet."

Soldiers like Michelle Dyarman wonder what's taking so long. Dyarman, a former major in the Army reserves, was involved in two roadside bomb attacks and a Humvee accident in Iraq in 2005.

Today, the former dean's list student struggles to read a newspaper article. She has pounding headaches. She has trouble remembering the address of the farmhouse where she grew up in the hills of central Pennsylvania.

For years, Dyarman fought with Army doctors who did not believe that she was suffering lasting effects from the blows to her head. Instead, they diagnosed her with an array of maladies from a headache syndrome to a mood disorder.

"One of the first things you learn as a soldier is that you never leave a man behind," said Dyarman, 45. "I was left behind."

In 2008, after Dyarman retired from the Army, Veterans Affairs doctors linked her cognitive problems to her head traumas.

Dyarman has returned to her civilian job inspecting radiological devices for the state, but colleagues say she turns in reports with lots of blanks; they cover for her.

Dyarman's 67-year-old father, John, looks after her at home, balancing her checkbook, reminding her to turn the oven on before cooking. The joyful, bright child he raised, the first in the family to attend college, is gone, forever gone.

"It hurts me, too," he said, growing upset as he spoke. "That's my daughter sitting there, all screwed up. She's not the kid she was."

Walkie Talkies

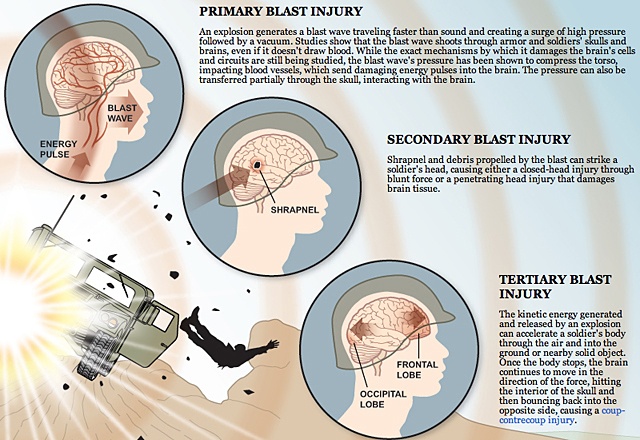

Better armor and battlefield medicine mean troops survive explosions that would have killed an earlier generation. But blast waves from roadside bombs, insurgents' most common weapon, can still damage the brain.

The shock waves can pass through helmets, skulls and through the brain, damaging its cells and circuits in ways that are still not fully understood. Secondary trauma can follow, such as sending a soldier tumbling inside a vehicle or hurling into a wall, shaking the brain against the skull.

Not all brain injuries are alike. Doctors classify them as moderate or severe if patients are knocked unconscious for more than 30 minutes. The signs of trauma are obvious in these cases and medical scanning devices, like MRIs, can detect internal damage.

But the most common head injuries in Iraq and Afghanistan are so-called mild traumatic brain injuries. These are harder to detect. Scanning devices available on the battlefield typically don't show any damage. Recent studies suggest that breakdowns occur at the cellular level, with cell walls deteriorating and impeding normal chemical reactions.

Doctors debate how best to categorize and describe such injuries. Some say the term mild traumatic brain injury best describes what happens to the brain. Others prefer to use concussion, insisting the word carries less stigma than brain injury.

Whatever the description, most soldiers recover fully within weeks, military studies show. Headaches fade, mental fogs clear and they are back on the battlefield.

For a minority, however, mental and physical problems can persist for months or years. Nobody is sure how many soldiers who suffer mild traumatic brain injury will have long-term repercussions. Researchers call the 5 percent to 15 percent of civilians who endure persistent symptoms the "miserable minority."

A study published last year in the Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation found that, of the 900 soldiers in one battle-hardened Army brigade who suffered brain injuries, most of them mild, almost 40 percent reported having at least one symptom weeks or months later.

The long-term effects of mild traumatic brain injuries can be devastating, belying their name. Soldiers can endure a range of symptoms, from headaches, dizziness and vertigo to problems with memory and reasoning. Soldiers in the field may react more slowly. Once they go home, some commanders who led units across battlefields can no longer drive a car down the street. They can't understand a paragraph they have just read, or comprehend their children's homework. Fundamentally, they tell spouses and loved ones, they no longer think straight.

Such soldiers are sometimes called "walkie talkies" -- unlike comrades with missing limbs or severe head wounds, they can walk and talk. But the cognitive impairments they face can be severe.

"These are people who go on to live" with "a lifelong chronic disability," said Keith Cicerone, a leading researcher in the field. "It is going to be terrifically disruptive to their functioning."

An increasing number of brain-injury specialists say the best way to treat patients with lasting symptoms is to get them into cognitive rehabilitation therapy as soon as possible. That was the consensus recommendation of 50 civilian and military experts gathered by the Pentagon in 2009 to discuss how to treat soldiers.

Such therapy can retrain the brain to compensate for deficits in memory, decision-making and multitasking.

A soldier whose injuries are not diagnosed or documented misses out on the chance to get this level of care -- and the hope for recovery it offers, say veterans advocates, soldiers and their families.

"Talk is cheap. It is easy to say we honor our servicemen," said Cicerone, who has helped the military develop recommendations for appropriate treatments for soldiers with brain injuries. "I don't think the services that we are giving to those servicemen honors those servicemen."

Missing Records

The military's handling of traumatic brain injuries has drawn heated criticism before.

ABC News reporter Bob Woodruff chronicled the difficulties soldiers faced in getting treatment for head traumas after recovering from one himself, suffered in a 2006 roadside bombing in Iraq. The following year, a Washington Post series about substandard conditions at Walter Reed Army Medical Hospital described the plight of several soldiers with brain injuries.

Members of Congress responded by dedicating more than $1.7 billion to research and treatment of traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress, a psychological disorder common among soldiers returning from war. They passed a law requiring the military to test soldiers' cognitive functions before and after deployment so brain injuries wouldn't go undetected.

But leaders' zeal to improve care quickly encountered a host of obstacles. There was no agreement within the military on how to diagnose concussions, or even a standardized way to code such incidents on soldiers' medical records.

Good intentions banged up against the military's gung ho culture. To remain with comrades, soldiers often shake off blasts and ignore symptoms. Commanders sometimes ignore them, too, under pressure to keep soldiers in the field. Medics, overwhelmed with treating life-threatening injuries, may lack the time or training to recognize a concussion.

The NPR and ProPublica investigation, however, indicates that the military did little to overcome those battlefield hurdles. They waited for soldiers to seek medical attention, rather than actively seeking to evaluate those in blasts.

The military also has repeatedly bungled efforts to improve documentation of brain injuries, the investigation found.

Several senior medical officers said soldiers' paper records were often lost or destroyed, especially early in the wars. Some were archived in storage containers, then abandoned as medical units rotated out of the war zones.

Lt. Col. Mike Russell, the Army's senior neuropsychologist, said fellow medical officers told him stories of burning soldiers' records rather than leaving them in Iraq where anyone might find them.

"The reality is that for the first several years in Iraq everything was burned. If you were trying to dispose of something, you took it out and you put it in a burn pan and you burned it," said Russell, who served two tours in Iraq. "That's how things were done."

To improve recordkeeping, medics began using pricey handheld devices to track injuries electronically. But they often broke or were unable to connect with the military's stateside databases because of a lack of adequate Internet bandwidth, said Nevin, the Army epidemiologist.

"These systems simply were not designed for war the way we fight it," he said.

In 2007, Nevin began to warn higher-ups that information was being lost. His concerns were ignored, he said. While communications have improved in Iraq, Afghanistan remains a concern.

That same year, clinicians interviewed soldiers about whether they had suffered concussions for an unpublished Army analysis, which was reviewed by NPR and ProPublica. They found that the military files showed no record of concussions in more than 75 percent of soldiers who reported such injuries to the clinicians.

Nevin said that without documentation of wounds, soldiers could have trouble obtaining treatment, even when they report they can't think, or read, or comprehend instructions normally anymore.

Doctors might say, "there's no evidence you were in a blast," Nevin said. "I don't see it in your medical records. So stop complaining."

Problems documenting brain injuries continue.

Russell said that during a tour of Iraq last year, he examined five soldiers the day after they were injured in a January 2009 rocket attack. The medical staff had noted shrapnel injuries, but Russell said they failed to diagnose the soldiers' concussions.

The symptoms were "classic," Russell said. The soldiers had "dazed" expressions, and were slow to respond to questions.

"I found out several of them had significant gaps in their memory," Russell said. "It wasn't clear how long they were unconscious for, but the last thing they remember is they were playing video games. The next thing they remember, they are outside the trailer."

Another doctor told NPR and ProPublica of finding soldiers with undocumented mild traumatic brain injuries in Afghanistan as recently as February 2010.

"It's still happening, there's no doubt," said the military doctor, who did not want to be named for fear of retribution

Screened Out

After the Walter Reed scandal, the military instituted a series of screens to better identify service members with brain injuries. Soldiers take an exam before deploying to a war zone, another after a possible concussion in theater, and a third after returning home.

But each of these screens has proved to have critical flaws.

The military uses an exam called the Automated Neuropsychological Assessment Metrics, or ANAM, to establish a baseline for soldiers' cognitive abilities. The ANAM is composed of 29 separate tests that measure reaction times and reasoning capabilities. But the military, looking to streamline the process, decided to use only six of those tests.

Doubts immediately arose about the exam, which had never been scientifically validated. Schoomaker, the Army surgeon general, recently told Congress that the ANAM was "fraught with problems" and that "as a screening tool," it was "basically a coin flip."

Military clinicians have administered the exam to more than 580,000 soldiers, costing the military millions of dollars per year, but have accessed the results for diagnostic purposes only about 1,500 times.

Rep. Bill Pascrell Jr., D-N.J., who has led efforts to improve the treatment and study of brain injuries, accused the military of ignoring the Congressional directive.

"We are not doing service to our bravest," Pascrell said. "There needs to be a sense of urgency on this issue. We are not doing justice."

Once in theater, soldiers are supposed to take the Military Acute Concussion Evaluation, or MACE, to check for cognitive problems after blasts or other blows to the head.

But in interviews, soldiers said they frequently gamed the test, memorizing answers beforehand or getting tips from the medics who administer it.

Just last summer, Sgt. Victor Medina was leading a convoy in southern Iraq when a roadside bomb exploded. He was knocked unconscious for 20 minutes.

Afterwards, Medina had trouble following what other soldiers were saying. He began slurring his words. But he said the medic helped him to pass his MACE test, repeating questions until he answered them correctly.

"I wanted to be back with my soldiers," he said. "I didn't argue about it.".

Senior military officials said problems with the MACE were common knowledge.

"There's considerable evidence that people were being coached or just practicing," said Russell, the senior neuropsychologist. "They don't want to be sidelined for a concussion. They don't want to be taken out of play."

If cases of brain trauma get past the battlefield screen, a third test -- the post-deployment health assessment, or PDHA -- is supposed to catch them when soldiers return home.

But a recent study, as yet unpublished, shows this safety net may be failing, too.

When soldiers at Fort Carson, Colo., were given a more thorough exam bolstered by clinical interviews, researchers found that as many as 40 percent of them had mild traumatic brain injuries that the PDHA had missed.

In a 2007 e-mail, a senior military official bluntly acknowledged the shortcomings of PDHA exams, describing them as "coarse, high-level screening tools that are often applied in a suboptimal assembly line manner with little privacy" and "huge time constraints."

Col. Heidi Terrio, who carried out the Fort Carson study, said the military's screens must be improved.

"It's our belief that we need to document everyone who sustained a concussion," she said. "It's for the benefit of the Army and the benefit of the family and the soldier to get treatment right away."

Gen. Peter Chiarelli, the Army's second in command, acknowledged that the military has not made the progress it promised in diagnosing brain injuries.

"I have frustration about where we are on this particular problem," Chiarelli said.

Fundamentally, he said, soldiers, military officers and the public needed to take concussions seriously.

"We've got to change the culture of the Army. We've got to change the culture of society," he said, adding later, "We don't want to recognize things we can't see."

Skeptics

The shift Chiarelli envisions may be impossible without buy-in from senior military medical officials, some of whom are skeptical about the long-term harm caused by mild traumatic brain injuries.

One of Schoomaker's chief scientific advisors, retired Army psychiatrist Charles Hoge, has been openly critical of those who are predisposed to attribute symptoms like memory loss and concentration problems to mild traumatic brain injury.

In 2009, he wrote a opinion piece in the New England Journal of Medicine that said the "illusory demands of mild TBI" might wind up hobbling the military with high costs for unnecessary treatment. Recently, Hoge questioned the importance of even identifying mild traumatic brain injury accurately.

"What's the harm in missing the diagnosis of mTBI?" he wrote to a colleague in an April 2010 e-mail obtained by NPR and ProPublica. He said doctors could treat patients' symptoms regardless of their underlying cause.

In an interview, Hoge said, "I've been concerned about the potential for misdiagnosis, that symptoms are being attributed to mild traumatic brain injury when in fact they're caused by other" conditions. He noted that a study he conducted, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, "found that PTSD really was the driver of symptoms. That doesn't mean that mTBI isn't important. It is important. It's very important."

Other experts called Hoge's posture toward mild TBI troubling.

To be sure, brain injuries and PTSD sometimes share common symptoms and co-exist in soldiers, brought on by the same terrifying events. But treatments for the conditions differ, they said. A typical PTSD program, for instance, doesn't provide cognitive rehabilitation therapy or treat balance issues. Sleep medication given to someone with nightmares associated with PTSD might leave a brain-injured patient overly sedated, without having a therapeutic effect.

"I'm always concerned about people trivializing and minimizing concussion," said James Kelly, a leading researcher who now heads a cutting-edge Pentagon treatment center for traumatic brain injury. "You still have to get the diagnosis right. It does matter. If we lump everything together, we're going to miss the opportunity to treat people properly."

***

At her family farm outside Hanover, Pa., Michelle Dyarman has a large box overflowing with medical charts, letters and manila envelopes. They are the record of her fight over the past five years to get diagnosis and treatment for her traumatic brain injury.

After her last roadside blast in Baghdad, which killed two colleagues, Dyarman wound up at Walter Reed for treatment of post-traumatic stress.

Over the course of two and a half years, she received drugs for depression and nightmares. She got physical therapy for injuries to her back and neck. A rehabilitation specialist gave her a computer program to help improve her memory.

But it wasn't until she began talking with fellow patients that she heard the term mild traumatic brain injury. As she began to research her symptoms, she asked a neurologist whether the blasts might have damaged her brain.

Records show the neurologist dismissed the notion that Dyarman's "minor head concussions" were the source of her troubles, and said her symptoms were "likely substantially attributable" to PTSD and migraine headaches.

"It was disappointing," she said. "It felt like nobody cared."

When she was later given a diagnosis of traumatic brain injury by Veterans Affairs doctors, she said she felt vindicated, yet cheated all at once.

"I always put the military first, even before my family and friends. Now looking back, I wonder if I did the right thing," she said. "I served my country. Now what's my country doing for me?"