Everything is Yours, Everything is Not Yours

Clemantine Wamariya, who at age six fled the Rwandan genocide with her sister, spent seven years wandering central Africa as a refugee, eventually coming to the United States and succeeding by every conventional marker. Judges called the piece “clear-eyed,” “tremendously insightful,” and “gracefully and honestly told.” Originally published by Matter in June, 2015.

At age six, I ran away with my sister to escape the Rwandan massacre. We spent seven years as refugees. What do you want me to do about it? Cry?

By Clemantine Wamariya

and Elizabeth Weil

Portraits by Andrew White

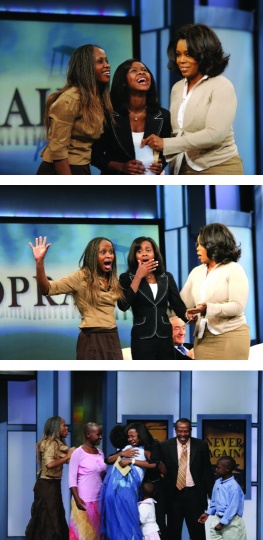

The day we taped the Oprah show, in 2006, I met my sister Claire at her run-down, three-bedroom apartment in Rogers Park, where she lived with the three kids she had before age 21, thanks to her ex-husband, an aid worker who’d picked her up at a refugee camp. A black car arrived and drove us to downtown Chicago. I was a junior at New Trier High School, living Monday to Friday with the Thomas family in Kenilworth, a fancy suburb. Claire, unlike me, was not a kid when we got asylum in the United States, so nobody sent her to school or took her in. Instead, she worked as a maid, cleaning 200 hotel rooms a week. All I knew about The Oprah Winfrey Show we were taping was that it was a two-part series: the first, a segment of Oprah and Elie Wiesel visiting Auschwitz, God help us; the second, the 50 winners of Oprah’s high school essay contest, of which I was one. All of us winners had written about why Wiesel’s book Night, his gutting story of surviving the Holocaust, is still relevant today. I dictated my essay to Mrs. Thomas, my American mother, who packed my lunch and drove me to school. I said that maybe if Rwandans had read Night, they wouldn’t have decided to kill each other.

Oprah sat on stage on a white love seat, next to tired, old Elie Wiesel, who sat in a white overstuffed chair. Oprah said glowing things about all the winners except me, which I told myself was fine. I hadn’t really gone to school until age 13, and when I was seven, I’d celebrated Christmas with a shoebox of pencils that I’d buried under our tent so that nobody would steal it. But then Oprah leaned forward and said, “So, Clemantine, before you left Africa, did you ever find your parents?”

I had a mic cord tucked under my black TV blazer and a battery pack clipped to my black TV pants, so I should have known something like this was coming. “No,” I said.

“So when was the last time you saw them?” Oprah asked.

“It was 1994,” I said, “when I had no idea what was going on.”

“Well, I have a letter from your parents,” Oprah said, like we’d won a game show. “Clemantine and Claire, come on up here!”

Claire kept on her toughest, most skeptical face, because she knows more about the world than I do. I leapt up onto the set smiling, because I learned some really useful skills as a refugee — like, I always could read what people wanted me to do.

“This is from your family, in Rwanda,” Oprah said, handing me a tan envelope. “From your father and your mother and your sisters and your brother.” Claire and I did know that our parents were alive, but we’d barely talked to them because — how do you start? Why didn’t you look harder for us? How are you? I’m fine, thanks, now working at Gap, and I’ve found it’s much easier to learn to read English if you also listen to audio books? I opened the envelope and pulled out a sheet of blue paper. Then Oprah, thank God, put her hand on mine. She stopped me from unfolding it, a huge relief. I didn’t want to have a breakdown on TV.

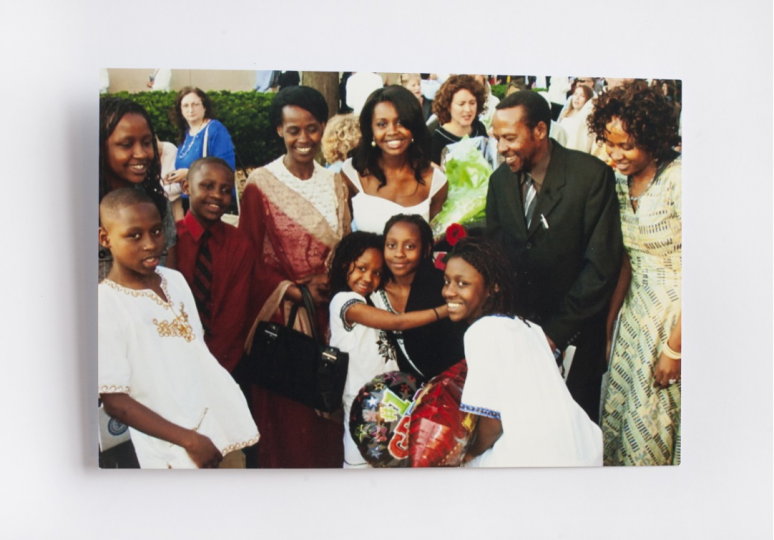

I started walking backward. Claire’s jaw unhinged, a caricature of shock. Then a door, that weirdly had images of barbed wire on it, opened stage right and out ran an eight year old boy, who was apparently my brother. He was followed by my father, in a dark suit, salmon shirt, and tie; a shiny new five-year-old sister; my mother in a long blue dress; and my sister, Claudine, now taller than me, who I’d last seen her when she was two and I still believed my mother picked her from a banana tree. I’d fantasized and prayed about this moment so many times. I used to write my name in dust on buses, hoping my mother would see my loopy cursive “Clemantine” and realize that I was alive. I saved coins, so I could buy my parents presents.

Claire remained frozen. But I, in my newly-purchased TV clothes and blown-out hair, ran toward my family, arms outstretched. I hugged my brother. I hugged my father. I hugged my tiny little sister. I tried to hug my mother but my knees gave out — I guess I was a cartoon, too — and my mother had to pick me up. Then I hugged her. I hugged Claudette. I walked across the stage and hugged Oprah and the lovely, weathered Eli Wiesel. The cameras were so far away that I forgot I was participating in a million-viewer spectacle, though I was aware enough to realize that everybody in the audience was crying, including the one other Rwandan essay contest winner. I wiped my eyes, put my hand on her shoulder, and said, “My mother is your mother, too,” which probably offended the hell out of her.

Then we were ejected onto the sidewalk outside Harpo Studios and my whole new family took a black car north to my sister’s apartment. Nobody knew what to do. My mother kept sitting down and standing up, and touching everything, and singing about how God had protected us and now we must serve and love him. My father kept smiling, like someone he mistrusted was taking pictures of him. Claire remained catatonic; I thought she’d finally gone crazy, for real. I sat on Claire’s couch, looking at my strange new siblings, the ones that had replaced me and Claire. I fell asleep crying and woke still wearing my Oprah shoes.

The next day was Friday. Of course, I didn’t go to school. I couldn’t look at my parents — they were ghosts. I felt gratitude, sure, but I also felt kicked in the stomach, like my life was some sicko psychologist’s perverse experiment: Let’s see how far can we take a person down, and then how far can her raise her up, and then let’s see what happens! My mother loved to garden in my early childhood home, so Saturday we went to the Chicago Botanical Garden. We did Navy Pier — Ferris wheel, cotton candy, all the tourist stuff. My father kept smiling his fake, pained smile. Claire never said a word. Then, Monday morning, my parents and new siblings left on the flight back to Rwanda that Oprah’s people had booked for them. I caught a Red Line and then the Purple Line train back up to Kenilworth. Mrs. Thomas picked me up at the station and dropped me at school. Clemantine’s Oprah shoes, worn only once since being on the show.

In 1993, when I was five, I started kindergarten. I considered myself the most special child there, maybe the most special child in the whole world, because one day my nanny picked me up carrying a rain coat and kelly green rain boots that had belonged to Claire, and she also told me stories that made sense of the world, like that the gods shook out the ocean like a rug to make waves. But that nanny, who I loved, disappeared. A few months later my new nanny came to kindergarten to pick me up. On our way home, we passed a group of men singing, dancing, and drumming in the street, on a corner where we often bought sugar. I wanted to stop and dance with them — I’d never seen these people before, so it was exciting and exotic, and the dancers were blocking the dusty road anyway, not letting cars pass. But that nanny, who had a history of plying my patience with mandazi, or beignets, so that she could talk to her friends, refused. At home I tattled. “You shouldn’t have walked that way,” my mother said to her sharply. A few days later that nanny disappeared. I never went to kindergarten again.

˙ Clemantine on a train from Philadelphia to New York.

You know those little pellets you drop in water that expand into huge sponges? My life was the opposite. Everything shrunk. I was forbidden to play in the mango tree, then forbidden to play outside. Our curtains, which my mother threw open at five each morning, suddenly remained closed. The drumming began, loud and far away. Then the car horns. My father stopped working after dark. My mother quit going to church. Instead she prayed in my room, where my whole family now slept, because it had the smallest window. We ate dinner with the lights off. My parents’ faces turned into faces I had never seen, and I heard noises that I did not understand — not screaming, worse. My parents whispered and I eavesdropped. I heard them say that some robbers had ransacked our neighbor’s house and left a note saying they’d soon return for their girls.

By then I was six. No one would explain anything to me — no parable for the world closing in on itself, like the sky kissing the ground to make the morning dew. Then one day my mother told Claire to pack a few things, to go to my grandmother’s farm, which we loved. At her house we never even wore shoes. The next morning a van from my father’s car service arrived. My mother handed me a bag and put me in the van alongside Claire. She made me promise to behave. She hugged us and said she’d see us soon.

On the way out of Kigali, we stopped to pick up two of my cousins — girls Claire’s age. The driver knocked on the door. Nobody came out. We stopped at other houses; other girls entered the van. We all squished together in the middle of the bench seats, away from the windows. For some time we crouched on the floor. Claire told me we needed to play the silent game. The drive took forever. We didn’t even stop to eat kabobs or buy the soap that we always brought to my grandmother as a gift.

At my grandmother’s, some of my uncles and cousins were already in her kitchen, the older girls peeling potatoes like city girls — not well. I idolized these cousins, their black freckles and fancy clothes. My grandmother circled them like a lion, livid. Earlier that day they’d snuck out of her house and walked down the street, to borrow a neighbor’s skin lotion.

Every hour I demanded an update on when my parents were coming — or at least my brother, who we called Pudi, because he loved Puma and Adidas. My grandmother, cousins, and sister all just said, “Soon.” Nobody would play with me. I felt outraged at my mistreatment. I stopped eating and bathing and refused to let anyone touch my hair. After a few nights my grandmother said, with zero enthusiasm, “Let’s play hide and seek,” and she took me, Claire, and my cousins to a different house to sleep. The following night she said, “let’s hide again.” This time she told us to climb inside the deep pit in the ground that was used to make banana wine.

When it happened, we heard a knock on the door. My grandmother gestured for us to be silent and then, she motioned for us to run, or really, to belly-crawl through the sweet potato field. I carried a blanket, which turned out to be a towel. Claire pulled my arm. Once we crawled through the field and reached the tall trees, we ran, for real, off the farm and deep into a thick banana grove, where we saw other people, most of them young, some of them bloody with wounds. We walked for hours, until everything hurt, not toward anything, just away. We crouched down by a stream to drink. I started shivering, despite the heat, and said to Claire, “I want to go home.”

She stood up, yanked my wrist, and said, “We can’t stay here. Other people will come.”

That night it rained a sticky, thick syrup. I held on to Claire’s shirt, too exhausted to hold hands. A woman tried to give us food, but we were too afraid to take it. A man told us he knew the way to safety. We followed him to the Burundi border, to the Akanyaru River. There were bodies floating in it. I was so young that I assumed they were asleep.

All my toe nails fell out. We lived off fruit. We found an abandoned house and spent the day hidden under a bed. After days, a week — who could keep track? — we found a cornfield where we heard children playing. Their cries now sounded exotic. Hadn’t the whole world changed? Claire decided that we needed to find these playing children’s parents. When we did she told them that we’d come from over the hill and that our family would follow soon. The mother accepted this non-explanation and took us to her one-room hut where she slept with her family on a bed of straw. All night I itched. In the morning I woke with welts and the children laughed at me for not knowing what lice was. We stayed there, working in the fields and eating boiled corn and sweet potatoes with no oil or salt — the worst cooked food I’d ever consumed. Then a few weeks later, we saw people walking down the roads, hundreds, maybe thousands, carrying bags, children, baskets, and faded clothes on their heads. One man carried a dog. Claire decided we needed to join them.

“What if you go and you don’t find anything?” the mother of the hut asked us.

Claire said, “We need to go.”

At the end of that year my teacher told our sponsor at church that I really should be in a better school. So our sponsor asked around the community and the Thomases, also members of the church, agreed to take me in. I lived with their family Monday to Friday. It was amazing, and I felt so overwhelmed. Mrs. Thomas read with me everyday — The Boxcar Children, The Little Prince. She hired me tutors and brought me on family vacations to Florida, but I didn’t want get too close: no I-love-you’s, no kisses goodnight. My sole focus was bootstrapping, working the American system, picking myself up out of my depths like some international Horatio Alger. At school, the cheerleaders looked happy, so I became a cheerleader. I ran on the track team. I acted in the school’s improv troupe. I peer counseled. I even fundraised with my school’s Aid for Africa club. Sometimes I misfired. Once I signed up for a church youth camping trip, which I didn’t quite process because Mrs. Thomas packed my bags for me. Then I arrived at Big Foot Beach State Park, looked around, and thought, what is this nightmare? Why on earth would you pay and sleep in a tent by choice?

Clemantine cheerleading in 7th grade at Christian Heritage Academy.

Around town, some people treated me like an egg, the poor, fragile refugee girl. People wanted to help in the ways that they wanted to help. One day one of Mrs. Thomas’s friends picked me up at school in her convertible, handed me a pair of sunglasses, and said, “We’re going shopping today. Call me Auntie Wilma.” She became my godmother of shopping. We drove to Nordstrom’s.

“Okay, here’s how it works,” she said. “You buy things you can mix with things you already have. It’s not only about trend but what will last longer.”

I liked clothes — and my new Auntie Wilma was being sweet; as much as anything, she wanted to teach me about my growing body. But I was also thinking, “Why are you doing this? Why should I care?”

On Fridays, I rode the L down to Rogers Park, stopping along the way at Blockbuster to spend the allowance the Thomases gave me on buckets of popcorn, soda, and rented movies. At Claire’s apartment, I made a pillow fort and spent the night inside snacking and watching movies with Claire’s kids — Mariette, eight; Frederick, five; and Michelle, two. My sister had so much responsibility. In addition to being a young mother, she was an extraordinary survivor. So just like we did in Africa, I took care of her children while she hustled and worked. Saturday mornings she headed to downtown Chicago to clean rooms at the Wyndham Hotel. I made pancakes and ice cream for breakfast for her three kids, then did all her family’s laundry, cooked, and froze meals for her family for the week, and made sure Mariette, Frederick, Michelle had plans after school. On Sundays, like good Rwandans, we went to church and pretended everything was great. That seemed to be the official policy of Rwandan culture: chin up, clothes ironed, don’t stand out. Sunday night, I returned to my life as a pampered child in suburban Kenilworth. Claire never resented it. She never knew that Mrs. Thomas made me three meals a day and that at the Thomases’ house I had a big cozy bedroom, my own bathroom, and no cockroaches. Clemantine and Claire in 2003 in Claire’s new apartment in Edgewater, Illinois, the first place she lived after leaving her husband.

A year after Oprah, Claire became a citizen and flew back to Rwanda, where my parents now lived on the outskirts of Kigali, in a shack. They’d lost everything in what people were calling the intambara — Kinyarwanda for “eruption” or “explosion”; how are you supposed to capture 800,000 people being killed by their friends and neighbors in 100 days? Two months after that first trip, Claire flew to Rwanda again, and this time brought my mother and youngest sister back to live in the United States. A few months later, my father, younger brother, and sister. Then my life became even more surreal. Like Claire, my parents didn’t talk about the past. They existed in a never-ending present, not asking too many questions, not allowing themselves to feel, moving forward inside a small, tidy life. Now on weekends, at Claire’s house, I’d see my little sister, who was six, jump into my mother’s lap — like anybody could just jump into our mother’s lap. She’d beg for my mother’s attention — like all lucky little girls do.

Clemantine, center top, graduating from New Trier High School in Illinois, surrounded by her Rwandan family: mom and dad on her left and right, Claire far right, and younger siblings, nieces, and nephews in foreground.

One Sunday, while I was doing my homework, I heard my mother in the kitchen, prepping beef stew and singing. When she finished, she sat next to me at the table, the first time we sat together like that in 14 years. Her dark skin didn’t match mine. Her hair was short and tight against her head — I remembered it as long. Her fingernails were chipped. Her lips were parched. Her singing sounded strange. The fantasy of reunion was a lie. No one could patch up my family and make it beautiful. The only things about my mother that conformed to my memory were her cheekbones and the white rosary she wore around her neck.

I ran to the bathroom and turned on the shower on full blast. After 20 minutes, Claire knocked on the door, annoyed.

“You are not taking a bath. Why are your eyes red?” she asked harshly. “Have you been crying? What happened?”

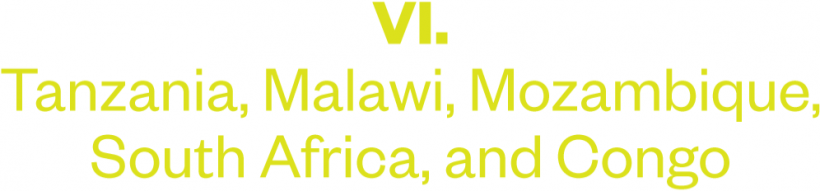

I started screaming, “Pudi! PU-DI!”, sure my brother would be here. Eventually the UNHCR aid workers corralled me back in line, to stand next to Claire. When we reached the front of the cue, a woman grabbed my hand and pushed it into a bucket of purple ink. The dye meant I had been counted. Nobody asked my name — too many people for names. We were given a tent, scratchy blankets, and a pot. A man pointed to the part of the hill where we should pitch our tent and to the hollow between the two hills where we should stand in line, once a month, to fill a plastic bag with maize and beans.

For a few hours I remained giddy — of course, we’d find our parents here. Then I looked around. Hundreds of sick on the ground, moaning. Dozens of wounded, yelling. The camp bathroom was located near the ditch that aid workers had dug for dead bodies. I was afraid to go; Claire wasn’t — she was as hard as amber by then.

But within a month, I too had built a tough, shellacked veneer. Each morning I walked two or three hours to fetch water and wood. Once at the pump, I waited in line for an hour more. The other women, who were probably only 17, tried to bully me out of my spot. “Are you going to able to carry that gallon? It’s bigger than your head. It’s bigger than your whole body.” I threw toward them my newly mastered do-not-fuck-with-me stare, which I’d developed by telling myself that I was twice as old and five times stronger than these pathetic women, who could only cope with their lives by making a six-year-old feel small.

Soon after, a handsome Congolese CARE worker declared that he was in love with Claire. Claire knew that we were targets, two girls without a guardian; she instructed me never to accept gifts like candy or bread. She told the CARE worker — who I’m going to call Rob and who, at the time, seemed extremely sophisticated and put-together, due to his well-cut hair, striped shirts, and shiny shoes — that she was too young to get involved, that the last thing she needed was to be a 16-year-old refugee without any parents and a little sister and baby to care for. But he persisted.

“Me, I want to marry you,” Rob said daily. “Me, I want to marry you. You can go to school.”

He claimed that he’d fallen in love with Claire on the day we entered the camp, and that if she married him, we could move to Congo and live with his mother.

After a few months, Claire broke down — of course she did. This life wasn’t going to lead anywhere anyway, and marriage (however personally problematic) was a lottery ticket out. Marriage came with papers. Besides, I had Claire to look after me, and Claire had no one to look after her. Claire and Rob married, surrounded by a few envious refugees and Rob’s friends and co-workers. The best things about the day were the mandazi and reception sodas.

After the wedding, Rob, for once, did his part. He helped us get the documents we needed to move to his mother’s, or really, his uncle’s house, in Uvira, DR Congo. My first few weeks there I constantly stood on the bed and touched the ceiling. We’d been sleeping outside for a year and a half. In Uvira, Claire got pregnant and everybody wanted to be my mother. Women would scrub my feet and bring me their daughters’ dresses. They’d say, “What is this mess?” and then fix my hair. Rob’s cousins, children close to my age, also lived in the house. We shared big plates of rice, eggplant, and fish stew. I ate the slowest. In March 1996, Claire, then age 17, went to the hospital, like a semi-regular person, and Mariette was born. I felt so loved and cared for. I attended a few months of first grade. I even started to forget Rwanda. Maybe this life in Congo was real and before was just a dream? But then the people started streaming from Bukavu, northeast into Uvira, fleeing the war breaking out between Mobutu and Kabila, knocking on doors of houses, including our house, begging for food. Rob’s family cooked extra fish stew and rice and took people in, but still they kept coming, stumbling off buses, flooding the markets, emptying the shelves. Claire realized this would only get worse and collected her jewelry and clothes, anything she could sell. She decided we needed to flee.

Entering Tanzania from Congo required crossing Lake Tanganyika, the deepest lake in Africa, a six-hour trip. Fifty frantic people, carrying their whole lives, crammed with us onto a small boat. We started taking on water as soon as we left the shore. The only way to slow our sinking was to make our boat lighter, to trade possessions for lives. So people started dropping heirlooms — framed pictures, silver, jewelry — and watching them sink. One woman tossed her china plates, one by one; then she started on glass teacups. Still the cold water kept rising, creeping up the adults’ shins, over my knees. I prayed to every saint that I could remember — Mary, Rose, Katherina. I promised God that if we made it to the other side he could kill me any way he wanted. I just didn’t want to die like this. Claire held Mariette, then eight months old, up to her chest. We reached Tanzania traumatized and exhausted and fell asleep near Lake Tanganyika’s edge. In the morning police rounded us up and put us in a boat. We resumed being refugees.

My writing in English was still not that great, so the Dean arranged for a post-grad scholarship year at Hotchkiss. Mrs. Thomas drove me out to Connecticut. She’d never been at an East coast boarding school before. Her own kids attended high-status universities — Duke, American, St. Olaf College — but as we drove onto the hundred-year-old estate of a campus, complete with boat house, cemetery, and two hockey rinks, Mrs. Thomas looked proud and confused. She’d done this: her family’s generosity had made Hotchkiss possible for me. But at some level, she expected life to have a certain order. Me being here wasn’t it.

At Hotchkiss, Claire’s attitude, along with my refugee skills, served me well: Whose behavior do I model to achieve in this place? Who has real power and who is bluffing? Where are the dangers and how do I escape? My ability to hack the system got me there, into those long halls filled with portraits of pale, square-jawed men. But it couldn’t protect me from my inner life. I was also alone for the first time, away from Claire and the Thomases. I was 20 and felt so old and so young. One day, in a philosophy seminar, I sat around a table with my fellow students, the boys in sports jackets, the girls in sweaters. It was a beautiful, crisp fall day. The professor gave us a thought experiment: You’re a ferry captain with two passengers. Your boat is sinking. One passenger is old and one is young. Who do you save?

With this, my veneer of decorum started to crack. Before I arrived on campus I asked the headmaster not to share my history. Nobody knew who I was. “Do you want to know what’s that really like?” I blurted out. “This is an abstract question to you?” Everybody stared.

A few weeks later, around that same seminar table — mahogany, with a view of the golf course — the professor asked us all to share the presentations we’d prepared on whether or not to send troops into a Black Hawk Down-like war scenario, like in Somalia. I cracked for real. “You have no idea, do you?” I yelled as one girl spoke. “You’ve never been in that scenario. What gives you a right to even talk? This is real. That’s me — and I have a name, and I’m alive and there are people out there who are dead, or they’re living but they’re checked out, and they hate the world because people in your country sat there and watched all of us getting slaughtered.” I ran out of class.

When I returned to fetch my bag, the professor asked me to meet him later in his office. He was in his mid-50s, with a salt-and-pepper beard, contained but kind. He told me that I needed to learn how to be a less emotional student. I did not agree. “I can’t be less emotional. It’s personal,” I said, all the while thinking that I didn’t survive all that horror to sip tea and join his club. I dropped the seminar and started therapy.

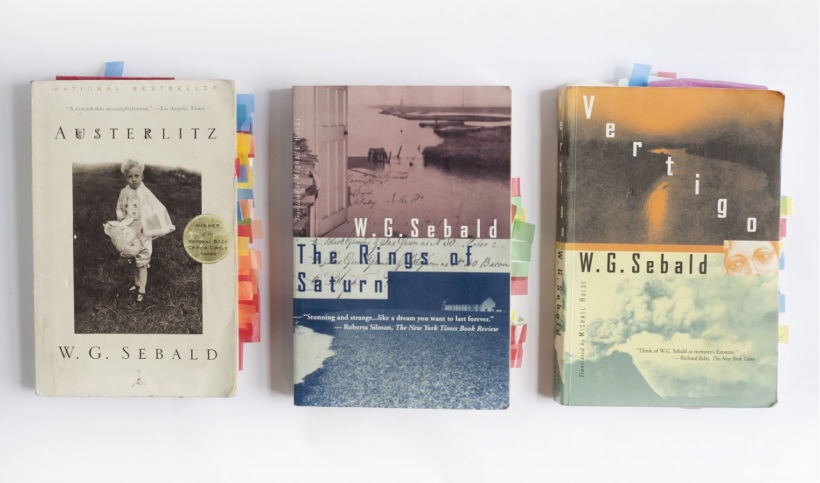

The following fall, at Yale, I tried again — psychology, history, and political science classes, to learn about the world abstractly. But those courses didn’t help me make sense of my life. I found them unnerving, intellectualized, and cold. So I built a private curriculum. My sophomore year I signed up for a class on the intense, inscrutable German writer W. G. Sebald because Sebald had written a book called On the Natural History of Destruction, and that sounded like my history. Sebald dropped into his books random-seeming photographs of libraries, eyes, animals, windows, and trees, as a way to try to capture the mass amnesia that fell over his country after the Second World War.

Ever since my freakout at Hotchkiss, I’d been on a mission to piece together who I was. I’d been looking at my hands — they were my mother’s hands. I’d been looking at my feet — my right foot in particular, it looked like my father’s foot. I knew I couldn’t understand myself through my American family or my classmates in their YALE sweatshirts and J. Crew skirts, even though I dressed like them. But I had so few concrete artifacts from my past — just a vinyl pencil case from South Africa and a photograph of myself at age four, dressed up for my aunt’s wedding, that I’d now hidden so deep that I could no longer find it. But Sebald offered a method, a technique for navigating out of the fog: He implied that if a person wades deep enough into memory, and pays close enough attention to the available clues, a narrative will emerge that makes moral and emotional sense.

Clemantine’s college copies of W.G. Sebald’s books.

I read all of Sebald’s books — The Rings of Saturn, The Emigrants, Vertigo. Then I started rereading. I also made a practice each day of walking by Annette, a woman who stood in front of Graduate Hall with a bucket of flowers that she purchased in bunches at the grocery store and sold as singles for a tiny profit. She was a fighter. Almost nobody noticed her until she called out, “Hey, sugar, come buy some of my flowers.” She had nothing to do with most students’ impressive, Ivy League lives. But to me she was a clue, a link to a buried past, a reminder of my sister who used to sell anything — salt, meat — so that she could save enough money for us to try to escape our deadening refugee lives. I had so many questions. Why did I use the GPS map on my phone, even on campus, when I knew where I was going? Why did I obsessively collect buttons and beads? Why did I talk so much — was I afraid I’d disappear? After Annette, I turned down Hillhouse Avenue and took pictures of the roots and vines growing outside the Yale cemetery. Then I studied the patterns in the images to see if they matched the patterns of the veins in my hands.

Once back in my dorm room, I retreated to the nest of pillows I built on my bed and pulled out my worn copy of Austerlitz, Sebald’s novel about a middle-aged man, who, as an infant, was shipped out of Czechoslovakia by his Jewish parents on the kindertransport, though nobody ever told him this. I twisted my earbuds to listen to Austerlitz on audiobook as I read. When my fair, green-eyed boyfriend, Ian, returned from his day — political science, crew team — I said, “Listen to this! Everything is connected!” I’d been with Ian for two years. I loved him and clung to him, but he often joked that I was having a more intense relationship with Sebald than I was with him. And it was true, in a way: I did want Ian to care more about Sebald, to interrogate the details of his own life. For instance, Ian was constantly playing and twisting pieces of paper or anything small in his hands, a nervous tic. But he wasn’t inclined to assigning much meaning to this, he didn’t want to investigate why he behaved as he behaved.

“Clemantine, you’re so weird,” Ian said, gently dismissing me.

Still, my own interrogations did not feel optional. Why did I drink only tea, never cold water? Why did I cringe when the sun turned red?

The Tanzania camp was horrible — not enough space or tents, day-long lines to bathe. Claire decided this was not a life that we could accept. She couldn’t spend one empty, hopeless, soul-destroying day waiting around for the next. So she sold most of her clothes and all her jewelry and we started walking again, endless days moving toward nothing I could understand, avoiding roads and refusing the comfort of joining larger groups, as roads and numbers increased the already miserable odds that we’d get caught and thrown in jail or sent back to a camp. We walked and got on cargo trucks when we could, until immigration picked us up and put us in a camp in Malawi. There, Claire followed a Somalian man selling black-market goat meat to his source, and she started selling meat as well. Once she saved enough money, we headed off again, south from Malawi through Mozambique, over 500 miles, through a mix of lush hills, palms, and desert plants that looked like the outskirts of Austin, Texas. Eventually immigration caught us again, and separated us from Rob.

Claire’s stoicism gave way to fury. “Aren’t you ashamed?” she screamed at our captors. “Do you know how hungry these children are? We walked from my country that’s at war.”

I said, “Yeah. Yeah. Yeah,” her self-appointed chorus. It was a relief to be away from Rob but we were scared. Two girls and a baby — we needed him. Rob was our door, our barrier against more predatory men. The next day the guards let us go.

Once again, walking, Claire resumed her silence. I knew by that point that Rob wanted to leave me behind. Unlike Claire, he did care that I walked slowly and she did not defend me against him when he made me abandon my beloved, ridiculous Mickey Mouse backpack. I couldn’t look at her — what if she saw my anger? My black pit of need? We walked another week or two, south toward Maputo, until immigration again picked us up and put us in a camp, this one surprisingly nice and run by Italians. I wanted to stay forever, but Claire felt staying in a good camp was even worse than staying in a bad one — what if we started to think this life was okay? Our second morning there, I polished her black boots. She put on her white blouse and flare jeans and she snuck off for a nearby town. The Italians who ran the camp fed the refugees by distributing boxes of pasta. Claire cut a deal with an Indian man who ran a grocery store. He paid Claire five Mozambican metical per box of pasta. Claire bought boxes off the refugees for one. In three months, she made enough money to buy us bus tickets to the South African border.

I resented everything about back-tracking to Rwanda. Why return to that hell? The only place on our way that I didn’t hate the thought of returning to was Congo, where we had what seemed like a family and a dozen women who brought me ironed dresses for church, braided my hair, and scrubbed my feet. But by the time we arrived — three years after we left, Claire by this point five months pregnant — the war had destroyed Congo. It was toppled and covered in ash, like a child had kicked over and burned a building-block town. Rob’s family huddled in their house, starving, living on sweet potato leaves. I spent my days, once again, under a bed, pushed away from the window, into the middle of the room, huddled so close to Mariette and Rob’s cousins that we could feel each other shake and breathe.

Claire did go to the hospital to give birth to Frederick, but even that building was bombed a few hours after he was born, so Claire wrapped him in a blanket and ran back to Rob’s uncle’s house, where she joined us under the bed. With no food Claire’s milk dried up within a week. She covered Frederick’s mouth with her hand, so the soldiers on the street could not hear him cry. Even once the fire fights died down, no one would let the children out — because all the adults knew. They knew people were all the same. They knew that we were scared and hungry, thus capable of becoming depraved. The Congolese Army was filled with war orphans (Kadogo), many close to my age, just 11 or 12 years old, children just like me but who hadn’t been forced to stay inside, so they’d wandered out and met a man with a rifle who offered them candy or stew. When the guns quieted during the day we could hear the birds singing. I stopped praying in the scripted Catholic way my mother had taught me. I just spoke to God directly: You say you’re in control and love us so much. Why are you not protecting everyone?

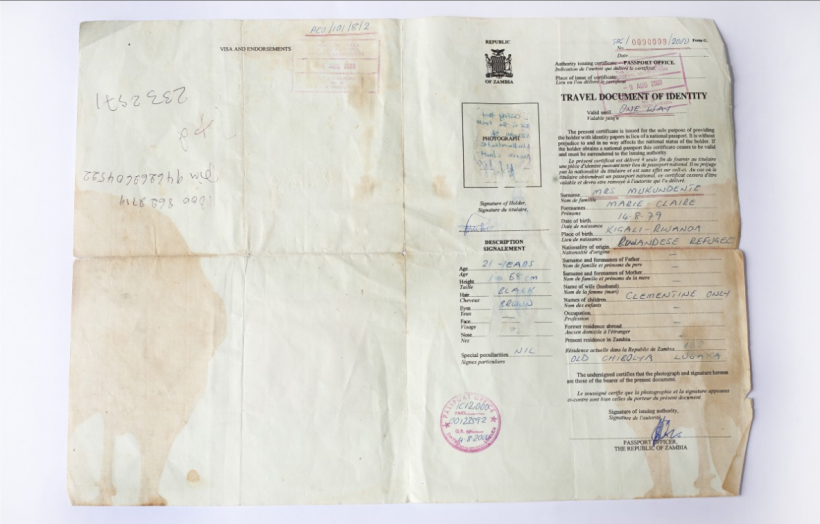

We never made it to Rwanda — still too unsafe. Instead we lived for a while in Zambia, where Claire worked her magic and got us all asylum in the United States through the International Organization for Migration, a refugee resettlement program. This was great, in theory. We’d have a country again and be able to start building a stable life. We left Africa in August 2000. I cried the entire flight to Chicago. No one would find us now.

Clemantine’s photograph from an 8th grade field trip to the battlefield at Antietam.

In 2011, I was invited to speak at a gala honoring Elie Wiesel at the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. I was then a junior in college. Mrs. Thomas’s friend wasn’t around to take me shopping, so I ordered a $100 dress online — red, with a shell top and a flounce at the waist. It fit horribly but I didn’t have time or money to buy another. I put on a black belt and declared myself good to go. The event filled with survivors and children of survivors, along with dozens of top fundraisers, all of whom made it their duty to remember and make the world remember, too. I was finally starting to realize what I meant to people, how my personal history could make me as relevant and powerful as any donor in the room.

People listen, and they don’t listen. They’re amazed and moved, and they look bored and proud of themselves, like they’re checking a box. I try to be relevant and not frightening. I totally freaked out watching The Hunger Games movie. Maybe you did, too? Some people pity me, and want to help me, and can’t stand the idea that I am not defeated and could help them as well. Others cast me as a martyr and a saint: You must be so strong, so brave. You must have learned so much. A few ask if I feel guilty for surviving. Uh, no. I did everything I could to survive. Do you think I should feel guilty for surviving? Do you feel guilty that on 9/11 you weren’t in one of the Twin Towers? I stand there and talk and ask people to investigate their lives and hope they stay awake. When people ask me what to do to ease human suffering, I don’t have a big answer. I just say, “Look, you have this one life. If you keep being selfish and unkind, it’s going to come back to you. Ask yourself why you’re scared, why you hate.” Almost every January, Claire flies back to Rwanda. She buys rice, beef, and potatoes, to throw a big New Year’s party for orphans. Then she puts on a fabulous dress, borrows my aunt’s most expensive bag, and makes me or my uncle, whomever is nearby, take hundreds of pictures of her. Back home, looking at the images, Claire’s daughter always asks, incredulous, “How could you possibly do that?”

Claire just shakes her head and laughs. “What do you want me to do? Cry?”

This story was written by Clemantine Wamariya and Elizabeth Weil. It was edited by Mark Lotto and fact-checked by Hilary Elkins. Portraits by Andrew White for Matter. Additional photographs by Anna Vignet.