Documenting the War Widows of Afghanistan

Robert Nickelsberg has been photographing in Afghanistan since 1988. When he returned to Kabul this fall, he thought of a new way to cover the complexity of the conflict, focusing on those left behind: war widows. “This is really what all those deaths add up to,” he said. “The challenge for a country to take care of its people.” A Dart Center Q&A.

Left: Jamella, left, 35, stands with Abida, right, also 35, in a hallway at Marastoon, a government-funded institution that houses war widows and those without any family support, September 2, 2015 in Kabul, Afghanistan. Right: Zahra Husseini, 45, sits in her apartment with a relative's daughter, Abida, September 3, 2015 in Kabul.

2015 was the deadliest year for Afghans since the United States invaded in 2001. More than 11,000 civilians were killed or wounded, almost 8,000 of them men. The wives of those killed joined the nearly 2.5 million widows in Afghanistan, a country that has endured varying degrees of armed conflict for the past three decades.

In a country where women rarely work outside the home, few widows have any education or job prospects. And those who qualify for government support often aren’t aware that they are entitled to it. For those who do know, obtaining regular support is its own conundrum. According to a United Nations report published last year, of the widows who do receive government support, the majority only receive a small one-time payment.

Photojournalist Robert Nickelsberg has been documenting the struggles of these widows. He spoke with the Dart Center’s Ariel Ritchin via phone about how his approach to covering conflict in Afghanistan has changed over the past 30 years, the challenges of photographing women there and his broader goals for this project. The following is a lightly edited version of that conversation.

Ariel Ritchin: Your first trip to Afghanistan was in 1988 to cover the Soviet occupation. What was that trip like?

Robert Nickelsberg: My very first trip was for a day only. The war between the Mujahideen, the Soviet army and the Afghan army had been going on for close to eight years. But in January of 1988 a very famous Afghan ethnic Pashtun leader died. He was living in Pakistan, and his last wish was to be buried inside Afghanistan. The president at that time, Mohammad Nahjibulah, granted a one-day cease-fire so that journalists and well-wishers could cross the border legally and attend his funeral in Jalalabad. This was a province that the Soviet army had carpet bombed pretty heavily.

About halfway through the ceremony, a series of bombs went off and pandemonium ensued. Everyone fled and I couldn’t find my car. At this point darkness had set in and I jumped into a car with a mad driving Pashtun heading back to Peshawar, Pakistan. The car had no windscreen and the twists and turns through the Khyber Pass were probably more hair-raising than the explosions themselves. The next day, there were reports of 17-25 people killed in those explosions.

AR: After that first experience, what made you keep coming back?

RN: The Soviets withdrew which made it possible to go to Kabul. It was a two-hour flight from New Delhi, where I was based. My modus operandi was to get as many current visas in my passport as possible. Kabul had been off limits for 10 years and it was a place I wanted to go back to as often as possible. The outside world had difficulty reaching me there and I had difficulty reaching it - there were just telexes, hardly any telephones. So you were really on your own and you had to produce every day. I was based in Delhi for 12 years and I don’t know how many times I’ve been to Kabul. Several dozen. When I moved back to the U.S. I continued to go on a regular basis.

AR: The Taliban took over in ’96 and had all kinds of rules that made it difficult to be a journalist. You needed to travel with a Taliban escort, you couldn’t take pictures of living things. How did you get your work done?

RN: Each trip was a challenge. You had to register with the foreign ministry when you landed and you needed an escort, a minder. Sometimes those minders were lenient and sometimes they were strict. You’d have to find out very quickly. I would start by raising the camera to photograph something innocuous, say, people getting on a bus at rush hour, and wait for their reaction. I could tell right away if the person was going to restrict my movements.

Photographing women was not allowed. You would try different angles, different approaches, pre-focusing the lens – this was before autofocus – so you could shoot underneath your arm from the car window and cough to hide the sound of the shutter. I can’t tell you how many off-horizon pictures I have, or pictures of my sleeve or of my shoes or pictures where a person’s head is cut off because I couldn’t quite get the lens up to eye level. And the proof was in New York, where the film was processed. I just had to hope that there was enough time before deadline to go back out and try again the next day.

I would try shooting out of my hotel window, sneaking out early in the morning and walking in the market, or offer them a tip at the end of the day and if they took it that was a good sign. Or I would try to slip away and just spray the area with my camera 180 degrees and then turn around and act as though I had just gone to have a cigarette. I would take the man for a big mid-day meal, fill his stomach and then try again to see how sweet that turned him.

There were also people who weren’t Taliban who would complain in public. Women knew the words “no pictures” very well. When you were confronted you had to quickly turn and walk in the other direction, to be non-confrontational. Writers were able to observe less conspicuously, but I had limited tricks in my bag.

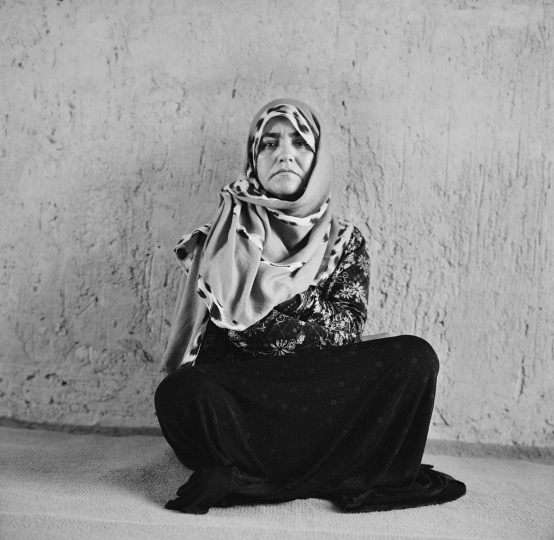

Abida, 35, sits in an office at Marastoon, a government-funded institution that houses war widows and those without any family support September 2, 2015 in Kabul, Afghanistan. Her husband, a taxi driver, died from injuries suffered in a suicide car bombing 2.5 years ago. She has 5 children, 2 stay with her at Marastoon and 3 stay with relatives outside of Kabul. As is customary in Afghanistan, marriage to her brother-in-law was offered. She declined. She then had to leave there in-law's house. There were no savings or pension from her husband. One of the doctors that treated her husband said she should sell one of her children to lighten the financial burden. Abida is taking tailoring classes at Marastoon and hopes to be more financially independent as a dressmaker.

AR: Since 9/11 you and many other journalists have been going back to cover the war. What is it like to photograph in Afghanistan now and how has it changed since your early days?

RN: Once the Taliban and Al Qaeda left Kabul and the countryside, there was a period of time after 2001 when foreigners and media were welcome. People were willing to open up and offer hospitality almost as though they had been liberated from the jailer. But that window started to close in 2004, 2005. It became harder to travel by road. Bandits started coming out and the no-man’s land became Taliban land. After that you had to fly. And now it’s very difficult to go more than 45 minutes outside of Kabul in any direction.

Security is just a lot more tenuous. You don’t know who’s who. More car bombs are going off and it’s much more difficult to cover acts of violence. There are fewer foreigners so you stand out. It’s a lot harder than when American and NATO forces came into the country in October 2001. Things have just gone backwards very quickly.

AR: What is different for the Afghans? People who are trying to make photos from that side?

RN: A lot of younger people have picked up cameras and realized they can bring in some money working for one of the many media organizations. But it isn’t a sustainable life anymore. At the peak a couple of years ago, before the Americans started withdrawing, there were so many media organizations looking to hire. Now they can’t pay much because advertising is down and the economy has shrunk. Foreigners aren’t there to buy high-priced items and a lot of people are trying to flee. There is an appetite for news and information, but it isn’t paying a living wage.

AR: You were back in Kabul this fall for the opening of your exhibition featuring 50 photos from your book Afghanistan: A Distant War. After 27 years of documenting wars in Afghanistan, what made you decide to focus on the country’s widows while you were there?

RN: In July, new figures came out about dead and wounded security forces and police in Afghanistan. They were so high this year that I had no choice but to take a different approach to the conflict.

When someone in the army or police force is killed, their families generally get a one-time stipend and they’re pretty much left on their own after that. Women in these situations are often illiterate or just a few years out of school – they’re at a serious disadvantage. And the government doesn’t have enough of a program in place to deal with these high numbers of widows.

AR: Can you talk about some of the challenges and limitations of photographing women in the country?

RN: For this project I contacted many NGOs, almost all of which were run by women. Being male, I would first ask if any women would agree to speak with me. Only a woman could make that initial contact with a widow.

There are some very traditional, conservative families that would not allow a man from the outside to come into the household or speak on the phone to a woman. There are different layers of tradition. Generally women live in the house of their husband’s family. If he leaves or dies, the woman is seen as a burden because she doesn’t have a job, is untrained and illiterate. One so-called “solution” is for her to marry her husband’s brother, for him to take a second wife. If the woman doesn’t agree, she is asked to leave or is thrown out. If she opts to leave she is thoroughly on her own but since she no longer has a man dominating her life, she is more likely to speak with me.

The next step is to ask if it is okay to work with a male translator. These are things you learn not only in Afghanistan but in Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and occasionally in Sri Lanka – every society has restrictions and sensitivities, but as long as you are respectful, things generally fall into place.

Often you only have that one opportunity and it’s generally a short one. Women are usually touched to see a foreigner visit them in their home, but you only have about a half hour before neighbors begin sniffing around. They’ll ask questions like: “What are these two foreigners doing there? Why all the cameras?” And they may start spreading rumors: “You’re taking money from them. You were with that man.”

Zahra Husseini, 45 years, sits in her apartment, September 3, 2015 in Kabul, Afghanistan. Zahra's husband died from injuries suffered in a rocket attack that landed in their rented shop during the late 1990's in Kabul. Zahra has been a cook at a Kabul non-government organization but out of work for two months due to severe pain in her shoulder. She has three sons one of whom is in Iran but paralyzed from a car accident. Her second son works in a bakery and earns $2.50 per day. Her third son goes to school. Zahra pays $20.00 monthly rent and hopes the NGO will pay for her shoulder surgery.

AR: If that type of risk exists, why do you think these women are willing to speak with you?

RN: For as long as I’ve been going to Afghanistan and before that, there have been war widows. Either through Soviet bombing, the Civil War, the Taliban, the constant fighting. Men have disappeared through torture, through jail, through false accusations, vendettas, revenge. And women are just left kind of helpless. When a man dies, a woman can’t go to the ministry of defense and say, “Where is my husband’s pension?” They have to send a man, who may or may not bring the money back. And the woman has no recourse.

So there is an opening here for them to tell their stories because not enough people are listening. There are opportunities for them, through foreigners, to get some assistance. One woman I spoke with, Zahra, had a torn rotator cuff. She was a cook. She would have to lift up a giant pot of rice and water onto the stove to cook the meal and she could barely lift a teacup. She was in unbelievable pain and hadn’t worked in two months. She needed an operation. The cost was $5,000 in Kabul and $1,500 in Pakistan. She had gone once to Pakistan to get diagnosed. But she had to make another trip and she would have to take her brother with her. So she needed more money, both to go and to pay for him as well.

She is willing to work, her small children are even working, but she is stuck. This is the situation. They are willing to tell you their stories in the hopes that there might be some recognition of their problem.

AR: So these women, like Zahra, who do leave the home to find work, are they more visible in public now? Does that change things?

RN: Since the Taliban left women are out on their own more, though they’re generally expected to be home before sunset. But security is still a major problem. There are fewer NGOs now, a lot have been attacked or threatened. Workers have been kidnapped from international aid organizations, like Doctors Without Borders. It’s really a very unpredictable situation now. Women are out in public more and more susceptible to violence, but they now know which intersections to try to avoid, where the car bombs have been before, to avoid the gridlock periods if they can.

Hamida stands for a picture where she works as a cleaning lady September 3, 2015 in Kabul, Afghanistan. She earns 10,000 afghanis or $160 per month. Hamida's husband was shot and killed by Taliban forces outside of Quetta, Pakistan where she and her family were taking refuge in the late 1990's. Being ethnic Hazaras and a Shia family, Hamida and her husband had to flee Kabul for Pakistan due to discrimination by the predominantly Sunni Taliban. Her eldest son was killed in a suicide bomb attack in Kabul. Hamida has three daughters and one son, who washes cars in Kabul. Her family returned from Pakistan once the Taliban were removed from power after 9/11.

AR: When looking at your work – both the photographs and accompanying text -- it’s clear that these women have opened up to you, that they trust you. But you only met with them for half an hour. How does that limit you?

RN: It’s rare to be able to spend more time with someone. You can only really do that with someone who has her own transportation where you can speak in the privacy of a car. I mean, look at the high walls around the homes. They’re put there so that nobody can look in and see the women. Privacy has to be respected, and women have to be careful.

I don’t know if it’s actually on the books, but it’s illegal for women to ride bicycles.

But there is a group of women who are pushing back and riding around the city. They get yelled at, they get harassed, they get catcalled, threatened. There are a lot of restrictions to become aware of if you try to go beyond those 30 minutes.

You’re not going to get all of the details. But the finer points often aren’t essential. We need to find out what happened since the incidence of violence, when her husband – say, a taxi driver – died in a car bomb. There aren’t police investigations for this kind of thing; there isn’t a prosecuting district attorney or an advocate. The women often don’t know all the specifics, and that has been true in all of the countries I’ve worked in in South Asia. Safia Tajweed, 36, sits in an office at Marastoon, September 1, 2015 in Kabul, Afghanistan. Safia's husband, a 40 year old Afghan Border Police officer was killed 3.5 years ago in Badakhshan Province after the Taliban overran his police post. When his body was returned, Safia was given a cash compensation of 100,00 afghanis, or $2,000. Since her husband's burial, she has not had any contact from the police and no word about his pension. She said a woman cannot go and fight for her rights especially with the military or police administrations. She has five daughters living with relatives outside of Kabul.

AR: Sounds like fact checking must have been difficult over the years?

RN: To some degree you have to rely on general statements or rough dates. They may have lost the birth certificate. Many don’t even know how old they are. When you start with that as your baseline, you hope there are some consistencies. And then the reporter or translator will go back over it to see if the story is consistent on the second telling.

AR: You mentioned serious logistical challenges, the difficulty of even finding these women. What precautions do you take for your own safety when you’re doing this work?

RN: If I’m going to an area downtown, I’ll let the driver or translator decide who will sit in the front seat. Being the foreigner, sometimes the police or security people will look in and wave us through. If I’m in the backseat and there are two Afghans in the front seat, we may get stopped.

AR: Why is that?

RN: If there’s a foreigner in the car, it may work for us or against us. On the way to the airport, the foreigner sits in the front because there are so many checkpoints along the way and foreigners curry less suspicion. In their eyes, we’re less likely to have something to hide. So you do those little things, try to blend in. They see the cameras but maybe that helps: we’re going to a press conference, we’re going to cover something.

There are different ways of shifting around the social strata and trying to outguess them. For example, show confidence and keep silent. Even though you may speak the language fluently, you shut up and act like a “dumb foreigner”. Know when to complain, when to get out of the car. Usually there’s a quick signal. You get out, act perfectly calm, patient, smile, shake hands. If you need directions, let your driver or fixer ask. Don’t try your Farsi or your Pashtu. But quickly follow up in English to build on something that was just talked about. Show that you understand.

I’ve gotten to check points where they’ve looked at my ID upside down and waved me through. Or you offer up your ID without being asked for it. The fact that you’re putting your cards on the table often results in the go ahead.

AR: What do you find most challenging about this project?

RN: Quite honestly, trying to get from one place to the other. Whole mornings can be spent just trying to arrange something. The logistics and trying to pack in as much work time in the course of the day or a week. I may spend two hours in traffic for a half hour picture taking session and then two hours in the car on the way back.

I remember we couldn’t find Zahra, the one with the pain in her shoulder. We thought we were on her block but then it took almost two hours to reach her. She couldn’t explain it properly because she’s rarely in a car. She talked about landmarks instead of which traffic circle to go around. And there are all kinds of unexpected things that happen at any given moment and you just try to manage them as best you can.

AR: What are your goals for this project?

RN: This project is about pulling back from and reflecting on the aftermath of violence and how it affects the everyday life of an average person. It really resonates differently than a breaking news situation or something focused on one side fighting the other. These people need our attention. And we need the public to respond. This is really what all those deaths add up to, the challenge for a country to take care of its people.