Essential Tips for Interviewing Children

Be human first. Do as much pre-reporting as possible. Find out what questions the child has been asking. When possible, immerse. Make them comfortable. Leave them in a good place. Verify what they’ve told you. And don’t underestimate them.

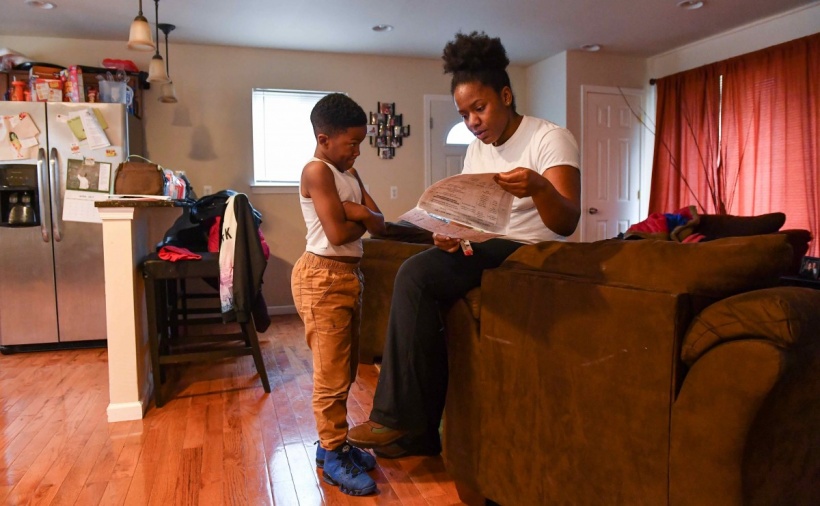

From John Woodrow Cox’s Dart Award-winning series on gun violence seen through the eyes of children: Second-grader Tyshaun McPhatter looks at his mom, Donna Johnson, as she reviews his schoolwork.

Editor's Note: In 2017 John Woodrow Cox wrote a remarkable series for the Washington Post on children and gun violence, which won the Dart Award for Excellence in Coverage of Trauma and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

Here, he shares some of what he has learned about interviewing children:

Be human first, a journalist second.

Reporters often meet people during or just after the worst moment of their lives, so start by telling both the children and their families that you’re sorry for what they’re going through. You’re there, hopefully, because you care, and they need to understand that.

Next, be clear about what you’ve come to do. If possible, send the parents links to previous stories that will give them a sense of your approach, and always explain to the children — no matter how young — who you are. If they don’t understand what a reporter does, take out your phone and show them your news organization’s website; if you have a physical copy of the newspaper or magazine, show them that, too. Explain your job in simple terms: “I’m a reporter, and I talk to people about what they’ve been through so I can tell their stories. I’m here to talk to you about what you’ve been through. Is that okay?”

Do as much pre-reporting as possible.

Before asking a kid sensitive questions, talk to their parents, siblings, teachers, therapists, mentors and anyone else who might have insight into the child’s psyche. Also, ask for permission (both from the parents and the children) to see what they’ve written, whether in school notebooks or personal journals or in text messages with friends. Deep pre-reporting will allow you to reconstruct moments you’ve missed, inform the questions you ask in an eventual interview and, most importantly, help you understand the child’s triggers — i.e., topics or words you should avoid.

Find out what questions the child has been asking.

Asking children how they feel seldom leads to anything more than a predictable, one-word response. In my experience, nothing will give you a better sense of a kid’s state of mind — and, specifically, what’s making them anxious — than the questions they ask the adults around them. In 2017, for example, I wrote about a second-grader named Tyshaun who, though he didn’t talk much about his emotions, did ask deeply revealing questions that gave me insight into how his father’s fatal shooting was affecting him. At home, he repeatedly pressed his mother about when and if the shooter would be arrested, because he feared the person would come after him, too. And at school, Tyshaun quizzed a social worker on the difference between heaven and hell, because he wanted to make sure his dad had gone to the right place. Those two questions told readers more about what Tyshaun was thinking than they ever would have learned from what he said in an interview.

When possible, immerse.

Observing children in their natural environment is often more fruitful than interviewing them. If you have the time and access, hang out at home, at school, wherever you can. You’ll learn things you never would have from asking questions, and you’ll give the child a chance to get to know you, which is essential to building trust.

No story better illustrates the power of this approach than the one my colleague Eli Saslow wrote in 2015 about a 16-year-old girl who had been wounded in a mass shooting. Instead of asking her to tell him what she’d endured, Eli waited for it come up organically. The payoff was extraordinary.

When it’s time to interview, make them comfortable.

When you need to do a more formal interview, ask the child where he or she feels most comfortable. Younger kids will almost always want to talk in their rooms. (Invite at least one parent to come along and remain there with you. Make clear that they can intervene at any time if they sense that their child needs a break.)

The initial goal is just to get kids talking, and there are few things they enjoy more than showing off their favorite possessions, so ask about them: favorite toys, books, games. This may not always be doable, but when I sense that children are comfortable enough to answer more difficult questions, I try to make sure that their eye level is equal to or above my own. For me, that usually means sitting on the floor. I never want to imply that I’m an authority figure, because I’m not. It’s important that they feel confident and in control, and it’s our job to make sure they do.

Start with simple questions that are generally related to the subject. If you’re talking to a girl who’s survived a school shooting, for example, consider asking about her favorite teachers and subjects. As you ease into the more sensitive topics, ask general, open-ended questions. Ask her to take you through that day in chronology, beginning with what she ate for breakfast, what clothes she wore, what she last said to her parents before going to school. When her mind wanders, which it will, gently bring the conversation back. If you’ve done enough pre-reporting, you’ll know which moments and memories warrant additional attention.

Finally, it must be said, if a child doesn’t want to talk, then don’t. The interview is over when they want it to be. That doesn’t mean you can’t try again another time, with the parents’ support, but never force the conversation.

Leave them in a good place.

At a 2018 Dart roundtable discussion, the journalist Lizzie Presser shared some tremendous advice a mental health expert had given her. In short, Presser said that when we take someone to a dark place in an interview, we should bring them back out of it before the interview ends. What that means for a kid is returning to something light and positive – their toys, friends, favorite TV shows – after the hard part is over.

Verify what they’ve told you.

Just like adults, kids get things wrong and their memories can be unreliable. It’s essential that you independently confirm that what they’ve told you is true and accurate.

Don’t underestimate them.

In my decade-plus as a reporter, the number of profound things I’ve heard children say far outnumber those I’ve heard from adults. Kids notice much more than many of us realize. They have a lot on their minds, and, usually, they share it without any knowledge of how their words fit into a larger context. What that leaves us with is refreshing and, sometimes, devastating honesty.

And yet, journalists still often rely on parents, teachers and police officers to speak for kids who have experienced trauma, leaving them as one-dimensional figures. Telling stories through the eyes of hurting children, or any children, isn’t easy, but it’s worth it. There are millions out there, and it’s our job to give them a voice.