Shooting Ghosts: A Journey Back from War

In September 2017, the Dart Center hosted journalists and Ochberg Fellows Finbarr O'Reilly and Thomas Brennan for a conversation about their joint memoir, Shooting Ghosts: A U.S. Marine, a Conflict Photographer, and Their Journey Back from War. Scroll down for the full event video and a lightly edited transcript.

A U.S. Marine from the 1st Battalion, 8th Marines, Alpha Company looks out as an evening storm gathers above an outpost near Kunjak, in southern Afghanistan's Helmand province.

Bruce Shapiro: Welcome, I'm Bruce Shapiro, executive director of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, based here at Columbia Journalism School. We're a center that brings together journalists, clinicians, researchers and scholars to think about how to tell stories about the most difficult experiences; how to tell stories about violence and conflict and tragedy, and, in particular, how to tell stories about aftermath and aftershock; about what happens when the shooting is over, when the cameras are gone and people are left to pick up the pieces. That's the work we do at the Dart Center, that's also the subject of Shooting Ghosts: A U.S. Marine, a Combat Photographer and Their Journey Back from War, by my friends and colleagues, Thomas J. Brennan and Finbarr O'Reilly.

Finbarr O'Reilly and Sgt. TJ Brennan at Outpost Kunjak, February, 2010.

There are a lot of books by war correspondents. As long as there have been reporters, they've gone to war. You can go back to Thomas Paine and to the 18th century. Reporters go to the front and come back and tell stories of what they see. There is also a pretty rich literature of soldier's memoirs, centuries of them. But the literature exploring the relationship between soldiers and journalists, what they experience together, how they look at each other, what their respective homecomings are like, that's a much smaller field. In fact, very few examples come to mind.

You could look at the work of the great Russian short story writer and journalist Isaac Babel who was, like Finbarr, embedded, in his case with the unit of Bolshevik soldiers during the war between the Soviet Union and Poland in the first year of the Soviet Union's existence. You could look at Stanley Kubrick's films, which deal in at least one case with a soldier and a journalist. But other than that, not much comes to mind. And yet soldiers and journalists spend a lot of time together, which is why we are so lucky that both Thomas and Finbarr have come back alive and well and professionally at the top of their game to talk about what they saw together, what they experienced together, what they experienced separately and together afterward, and where they are now.

We’ll talk about some of the things that they describe in Shooting Ghosts. We’ll talk about the craft of telling hard stories. We'll talk about trauma and recovery. The story of Shooting Ghosts is not really a war story; it's really a homecoming story. But it's mainspring, what turns this into something other than a routine homecoming memoir, if there is such a thing, is an event that Finbarr happened to catch on camera, and that is really where the action of this story begins.

BS: Before that incident, how did you each think about one another's jobs?

Thomas, who was this animal, this creature, this journalist who you had embedded with you? How did you think about what he was doing and what your responsibilities to him were?

Thomas Brennan: I'm still trying to figure him out. When I first met Finbarr, I was arriving after a three-day mission in Afghanistan, and when we showed up to the combat outpost there was this really skinny, gaunt man sitting in the corner, and I thought he worked with KBR, or some government contract agency. And then he told me he had cameras with him, and I wanted to shoot him in the foot and throw him over the side of the cliff.

It's just an added degree of stress. You don't necessarily get along with the media, you don't necessarily have the best impression of the media, and surely being a squad leader out in the middle of Afghanistan, I didn't have the best impression of having a journalist around.

BS: And, Finbarr, how did you think about not only Thomas but the rest of the crew that you embedded with? What was your relationship while you were working with them?

Finbarr O’Reilly: Well, this was my first time embedding with the Marines. I'd been with the Canadian Army in Kandahar. I'd been with the U.S. Army also in Kandahar. But this was my first time in Helmand, my first time with the Marines. And when I told a few U.S. army cadets that I was going to the Marines, they said, "Oh, okay, watch out, those guys live hard. They live rough." And they weren't kidding. I mean, you see that outpost, there's not much there.

So, I knew these were a pretty tough bunch of guys and a tight-knit closed group who have been fighting and training for months and aren't going to be very open to welcoming an outsider into that circle. So, I had to find a way to ingratiate myself. One of the tricks I knew was bringing packs of cigarettes, so I brought these cartons of cigarettes and tins of chewing tobacco which in this kind of remote place is like gold dust. I pretty much tried to bribe my way into the circle, and I guess it worked. But their big concern, and TJ's concern as the leader of this squad of 15 Marines in this very hostile Taliban stronghold, is he's got to get these guys home safely. He's got to look after them, he's responsible for them, and that's a huge burden. And to add an unknown element to that, I had to convince them that I wasn’t a liability. That I'm not going to get them hurt or injured by doing something stupid, wandering off on patrol, or stepping on an IED, or giving away a position, or just doing something really dumb. And the only way to do that was to step outside with them, to go on these patrols, and prove that I wasn't going to be a problem.

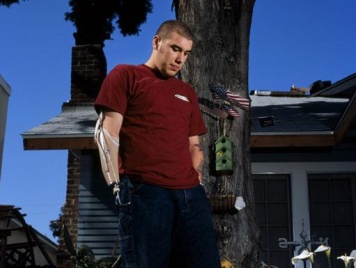

A concussed Sgt. Thomas James Brennan (C) of Randolph, Massachusetts rests in a compound offering cover after a rocket propelled grenade exploded near his position during a battle against Taliban insurgents in the town of Nabuk in southern Afghanistan's Helmand province, November 1, 2010.

BS: So, this RPG strike happens. You're concussed, blind, and before we move forward from that, there's another journalist to soldier and family interaction that happens that neither of you knows about at the time. Having to do with how your mom finds out about what happened to you.

TB: When I first got medevacked, I was put in the back of an armored vehicle and brought back to OP Kunjak, and Finbarr was on foot patrol. When I went back somebody handed me a satellite phone. I kept all of my Marines’ home phone numbers in my notebook, along with my wife's in case anybody had to call her on my behalf. So, I look up her number, I give her a buzz, and she tells me that what I told her was, "I got blown up, I've got my arms and legs, I love you, I'll call you, bye." And I just hung up the phone.

And when Finbarr came back, he asked me [if he could file his photos]. In hindsight, asking the concussed guy…

FO: However, in my defense, we had had the conversation in advance. TJ had asked me what I would do if something happened on patrol, and I told him I would take the pictures and stick to my agreement with the military: I would wait to file pictures until a family member was informed of a Marine's injury or death. But in this case, before we'd gone out on patrol TJ had said, "Look, if anything happens to me, I want people to know. I want people to know what my sacrifices are, because folks back home don't know what's happening over here." So, he had already given me consent.

TB: So in between the time that I called my wife, my wife called my father to let him know. My mom had a Google alert that had been set up for Finbarr's name, because there were pictures that were posted almost daily. So, she opened up her email at work and saw the picture of me slouched against the wall. She thought she had really just seen a picture of her dead son

against a wall, and she passed out. It wasn't until later that a coworker read the caption, which said that I had a concussion and that I wasn't dead,

FO: It does speak to the way that social media and the speed of the Internet changes things. In wars past, if a canister of film had been handed to somebody getting on an airplane, it wouldn't have been published until weeks later. Now it's minutes or hours after an incident – not quite real-time but almost. But the distance in terms of the experience of what we were going through is still huge. There's this disconnect that really is pretty wrenching.

BS: And one of the many revealing and honest moments in this book involves Thomas's mother's discussion with you about finding out this news in that way, and how she felt at the time.

FO: It's the opening, the prologue to the book. I feel pretty bad about how she learned about his injury. I’d had a couple of email exchanges with her. But when we finally end up together back in the U.S., and we go to visit TJ’s parents, I really wanted to make that apology in person so that I could really, in a way, be forgiven. They didn't hold anything against me, which I kind of knew, but it felt important to say something in person.

Marines from the 1st Battalion 8th Marines Alpha Company wake up and get out of sleeping bags to start the day at their remote outpost of Kunjak in southern Afghanistan's Helmand province, October 28, 2010.

We'll come back to that, but, Finbarr, you've been covering a lot of war by this point. And there's a point after this incident where it starts to get to you. You have this whole section that begins, "I try not to let the grimmer aspects of the job get me down. Like TJ, I've developed a mental checklist of my own. Reminders of things to do to keep me grounded." Eventually it does catch up with you. With a wounded soldier, he's got his purple heart, he's in the hospital, there's all kinds of ways of knowing that he's being functionally disabled by these injuries. How did you know?

FO: Well, it's a gradual thing. It's not like there's any one specific moment where I realize it. But there was a gradual kind of emotional numbing where I felt a distance from my girlfriend at the time, and difficulty relating to things back home in the way that I could relate to TJ in these conflict zones, or my colleagues when we would go out on these stories and experience the intensity of covering conflict in combat. There's this strong bond that we developed from being under fire together. And it's the same with fellow journalists.

Then you come home, and the everyday mundanity of life becomes difficult: Filing expenses, doing your grocery shopping, paying your electric bill. I was living in West Africa, the Internet was always going off, and the car was always breaking down. And all these little things sort of become huge things to deal with, even though they're pretty small.

I remember going out one night and getting into a scuffle with somebody at a bar, and coming home, and the guard at the house where I was living in West Africa wasn't there to open the door, and I'd had a couple of drinks and there was this mangy dog that used to hang around outside my house, and I just got out of the car and remember sort of kicking this dog in the ribs really hard and violently and sending it sort of yelping down the road away from me. When I got back into the car, my girlfriend just looked at me like, "What the hell is wrong with you?" And I kind of realized, "Okay, yeah, this isn't me, I'm not a violent person, I'm not somebody who does this kind of thing." And the next day, she said, "Look, you got to get some help." Military photojournalists, we like to be pretty macho guys, we like to think, “We're tough, we're strong, we're resilient.” But at a certain point you realize things aren't going that well, and that was the moment for me. I resisted it for a long time.

One of the things I would encourage people who find themselves denying the effects of what they have seen while working, whether it's in a war zone or at home, is if you're feeling troubled, talk to your peers, talk to your friends, talk to your family, and seek out the help you might need, rather than trying to be tough about it.

BS: One of the remarkable things about this book is that it takes us on a meticulous, meticulously remembered roller coaster ride that both Thomas and Finbarr individually go through. I'm going to read just a little bit of your account, and it's not one of the more graphic moments. There are moments involving inability to physically function in certain ways. There are moments when there's a suicide attempt, there's a lot of very off the charts stuff, but that’s not what this is:

"On the day of my appointment" – this is your first appointment at the deployment wellness center – "And as a Marine," – and I, a usage point for all journalists here. I used the word soldier generically a few minutes ago, Thomas leans over and whispers in my ear, “Marine.” This is a non-trivial difference, and it's the kind of thing you want to pay attention to.

"On the day of my appointment, I arrive at 0845 and sit for 30 minutes with other Marines and sailors in the cold waiting room of the mental health center. It's a place where no one makes eye contact or small talk. Nobody wants to be seen sitting here, just being in this place suggests you're broken. Rumors about damaged gear travels quickly.

Eventually a petite, olive-skinned woman calls my name, she looks Middle-Eastern. As she escorts me back to her office past a series of key card secured entryways, I wonder why she would be screening Marines who might be suffering from PTSD after serving in places like Iraq and Afghanistan. Her presence could be a trigger, or maybe this is just a twisted ruse to bring out the worst in a Marine.

As soon as I sit down, I begin to sweat. My fingers are trembling when we shake hands. The woman's gilded diplomas stare down at me from the walls. I'm sure she senses my anxiety. She reviews my personal information and deployment history, then she asks whether I've ever thought of killing myself. Holy shit. I don't even know this woman's name and that's her first question? I expected that question to be asked, but not like this. I feel violated, and wonder if this is how she treats all patients who've enrolled or been forced into therapy."

That recollection of an agonizing moment, and there are a lot of them in this book. First of all, why did you decide to revisit it? Why did you decide to tell those parts of the story, that may be at times exposing, embarrassing, hard for family members to read? There's a lot that's hard in there.

TB: I scribble frantically on a whole bunch of notes all the time, I'm like a hoarder of thoughts because I can't really keep them in my mind long enough anymore, so I just write them down and store them for later. I found myself sitting at home, or sitting in these waiting rooms taking notes, writing, and just trying to get things down on paper so I could process them later instead of torturing myself wondering what had happened, what I'm forgetting, and what I need to remember. And the common theme between the suicide attempt, seeking out help, the issues that my wife and I have faced, and stuff that happened between my mother and me: Loneliness was the common theme. I felt very alone going to those appointments and coming home from them. I even felt alone lying in bed with my wife. I wanted to revisit it all because everybody gets lonely every once in awhile, and what are you going to do when you have one more bad day and can't take it anymore? So, if it helps one person who understands the loneliness, it was worth it to me to revisit.

Also, the end of the day, sitting down and writing the book was therapeutic for me. I have hundreds of letters that my wife and I exchanged throughout my deployments; she kept hers, and I kept mine. I had to go through and read all of them; it was almost like my own form of exposure therapy. I got to look at it, talk to my wife about different things, talk to Fin about different things, my marines and my squad. I treated it like a reporting assignment, and it allowed me to arrange all of those thoughts that had been collected on paper and organize them into a book. I just hope it helps people.

Sgt. Thomas James Brennan smokes a cigarette in his bunk surrounded by photographs of his wife Melinda and their daughter Madison, 2, after a night of rain at the remote outpost of Kunjak in southern Afghanistan's Helmand province, October 29, 2010.

TB: One of my first journalism jobs when I got out of the Marine Corps was at the Daily News in Jacksonville, North Carolina, where I was doing daily beat reporting on the military. I was writing occasionally for The New York Times, but it took me, I think a little over a year, to write the story about my suicide attempt, and then to actually be in a place where I felt comfortable sharing it on such a public platform.

A week or so after the story had run, my desk line rings at the Daily News, and it's a Marine veteran telling me that he had searched online for clean, painless ways to kill himself, and that the search engine optimization on the New York Times story – my suicide attempt story – made it one of the first results. And he read it and wanted to call me and tell me that it was the reason he didn't kill himself.

That was just awesome. There's really no other way to put it. Knowing that you've made an impact on a truly, truly micro level. It goes back to reaching someone in his or her loneliest moment, because coming back from war, it sucks. Dealing with depression and mental health and brain injury. I'm sure everybody in this room has had a day when they didn't want to get out of bed.

FO: I think the point as well is that we're in these two professions – me as a conflict photographer, TJ as a Marine – where you're supposed to show this brave front on everything. And to punch through that kind of myth and stereotype, we have to reveal in the book our weaker moments, the moments we're not proud of. And the things we may even be ashamed or embarrassed of, and without those things the book doesn't have the kind of value that we want it to have. We really had to expose everything.

BS: You talk about your own isolation and loneliness. Even after you go to get help, you talk about your encounters with a psychiatrist and battling the voice within. You also talk about the extreme isolation you feel from, "London's boozy journalist culture," you say at one point. What began to get you out of that isolation? How did you begin to address it?

FO: I think this is one of the things about trauma: it’s isolating. And the instinct when you're feeling bruised or wounded in any kind of way is to withdraw. That's an evolutionary development. We want to withdraw to safety, and that safety is often within ourselves, and we kind of retreat to the shadows away from anything that might damage us further.

But that's the exact moment when we're most vulnerable, and we need to actually be engaging with people around us. And for me that was working with TJ.

So yes, I was the one who was mentoring him into journalism, as he wanted to write about his experiences. I encouraged him and connected him with the New York Times to do that series that went on to win the Dart Awards honorable mention. At the time, I was very much feeling at a loss journalistically, that my work wasn't having the impact that I'd hoped it would, and I was feeling very disillusioned and disheartened about being unable to change anything. But there was a very tangible result from helping this one individual. And that was transformative for me.

BS: But it's a big leap from having gone through this particular series of events together and talking about what a journalism career might look like to deciding to tell this intertwined story. It's hard enough to tell your own story. What made you decide to take this on as a joint project?

FO: While I was on my Nieman Fellowship studying the psychology of trauma at Harvard, I got really excited about soaking up all the information that I could about trauma and neuroscience. And I thought, "Wow, I want to write about this stuff. And I can use our story to get into it."

But as I started working on this idea, I realized that people don't actually want to read a bunch of neuroscience from a layperson. What they want is an interesting story with interesting characters, and I guess I thought we had something to contribute and that we both needed to process our experiences. And through talking with one another, and seeing the way that TJ was writing about his experiences – I'm a journalist, I was a news wire journalist, and our profession is meant to be objective and have this distance and not write in the first-person and not become this story. So, I was pretty reluctant initially to put myself out there in the same way that he was doing – but seeing the way that [writing] was having a positive impact on him, and also on the people he was writing for, I thought, "Okay, well, maybe I should give this a go as well." It was hard for me. The first drafts were very superficial and didn't dive quite as deep as we did in the book.

BS: And your voice in the book is a little more distanced and, even though it's first person, it's a little cooler. [TJ’s] is much more direct, raw.

FO: He's the Marine, he's got to be blunt.

BS: Well, you are a Marine, but you also have – and I think this is very important for those of us who are reporters thinking about writing about personal experiences – you also have that very direct access to detail and memory. You kind of let it pour out of you. You're observing yourself a little more, and you're just kind of there.

Now there's a craft part about telling a true trauma story. I'm talking as if you both are putting it all out there, and it's all just sort of vomited forth. But it's not. You have to decide how much detail to put in, who to name by name and who not. How much of yourself to expose and not. And to decide not only for yourself, but in collaboration with someone in this case. What was that process? What were your standards? This is a story about war, and a story about psychological breakdown, and a story about resilience in which many difficult things happen. And in which hopeful things happen. How did you decide, draft after draft after draft? What goes in and what doesn't? What's news, and what isn't?

FO: It felt pretty organic. It’s a chronological story, except for the first chapter, or the prologue, which really dumps us into the middle of the narrative. And then we backtrack to pretty much where we first meet. So, it was a question of writing out what had happened. And having a look at where there was overlap. And we originally started writing the book and sold the book proposal to the publisher with me writing about TJ in the third person. I was the journalist and he was, in a way, my subject. Even though he was writing his chapters, we wrote them in the third person, and I would do some interpretation and the journalistic thing.

After our meeting where the publishers bought the book, I said, "Why don't you try it in the dual first-person narrative?" And that's when TJ's voice really came through, and created this tension that runs through the book. And adds a great deal to it, and by that time he was here at Columbia and, the craft of his writing was getting so much better through his time writing for the New York Times. Things just started to make sense. And we would send the chapters back and forth and determine who was going to say what part when, and sort of try to get a sense of what felt natural in terms of the handoff. There were a few little structural tweaks as we went through various revisions, and cutting out some of excessive detail or overly florid language that I was a little more inclined to.

BS: Was it organic for you?

TB: Finbarr was living all over Africa and Israel, and he was in Gaza, and he was everywhere during the course of writing the book. So, he would send me a draft of his chapter, and I would go through it, make suggestions, and add little bits of detail. And he would do the same for me, and it was just a massive back and forth. Things went surprisingly smoothly. You’d think there would be a lot of tension, but really, we both had the end goal of writing a compelling narrative that was honest. We figured out a true vomit draft: put all of your emotions down, put all of your detail down. And then just pare it down and really try to get the concise narrative you're looking for.

FO: We had plenty of vivid scenes, so we would tend to write those first, and then try to work on the transition, on how to connect them. If you've got these big chunks of the body, then it's adding the connective tissue between them.

BS: You also got to know each other in a different way, as people do when you collaborate on a piece of writing. Trust works in a different way. You view one another in a different way. And there's a point in the book, in August of 2013 – I'm not going to do a spoiler, but you decided after years of knowing this guy, to tell him a story he had not heard before. A story about your involvement in the death of someone in Fallujah. It's a hard story. What made you decide at that point to trust Finbarr enough? What were the conditions that enabled this very important story?

TB: He was patient and not pushy, I think that was the biggest thing. He took the time to earn my trust. I'd had other interactions, and I still continue to have some interactions with people in our profession that don't take their time, and you feel 100% like a source. And it makes you walk away feeling used and violated. I mean having the first question be, "Please tell me about the worst day of your life." Whether it's surviving war, or it's rape or genocide, or whatever it is. Walking up and asking somebody about the absolute most terrible instance in their life is not cool.

It was my most traumatic moment. I stared into another human's eyes as he died. And watching the flicker of life leave another human from that close, that sticks around with you.

Finbarr and I were sitting on the front porch of my house. I'd known him for years at that point. And Finn was my friend, he wasn't just the cool journalist that I'd hung out with. He wasn't just this guy that I’d occasionally talk to, we were friends, and I trusted him. But it wasn't a story that I trusted a lot of people with, and I told him about it, and he wasn't like, "Holy shit, you're an evil person." He was accepting. He actually listened to my experience. And he wasn't immediately judgmental.

I think he knew the vulnerability I had to show to be willing to share such an intimate story. That scene in the book was something we discussed all the way up until days before the final manuscript was due, because it's just such a painful moment in my life.

A dust storm blows through Outpost Kunjak, in Southern Afghanistan’s Helmand Province, October 28, 2010.

FO: Up to that point, I thought that what was troubling TJ was the fact that he'd almost been killed in Helmand when I was with him. And I realized no, this runs much deeper. This is the moral weight of having killed in combat, and the guilt associated with that. These were things that he was grappling with on a far deeper level than the guilt of having some of his Marines wounded in Afghanistan. And it speaks to the depth of trauma that it took him almost three years to tell me this story. And then for us to decide how much, how important it was to include it in the book. And then we decided that we have to come forward and be forthcoming. There are so many layers and different kinds of trauma.

BS: It’s interesting to me that you went through this together. Somewhere in the book you quote our mutual friend Jonathan Shay, who's a psychiatrist, saying that, "Nobody deals with this alone." You were one another's supports. You each also have other supports, which you chronicle in the book. Your families, your medical providers and others. You come out of it, and the story also moves on to where you are now, or at least where you were when things end.

Talk about The War Horse, and what you're doing now.

TB: The War Horse is the only non-profit newsroom focused on the Department of Defense and the Department of Veteran's Affairs. It first started out with me wanting to do profiles of those killed in action, because I was really, really angry at the fact that you get these casualty announcements that are 30 words or 200 words, and it's just, wrong. So, I wanted to do something like that. And then coming [to Columbia Journalism School] I had various professors that said, "No, you need to think about diversifying it, you can't look as though you're just strictly pro-troops." So that's where we went. We do the good, the bad and the ugly. We do investigations, features, we hosted our first writing seminar here that Bruce was a guest speaker at.

BS: And those of you who follow military affairs nationally would also know that The War Horse got national headlines a few months ago for exposing the Marine's United scandal, involving online photo-sharing and harassment of women in the Marine Corps. That must have been challenging for you, in fact I know it was challenging for you. Talk about dealing with anger coming at you from the Marine Corps, and threats coming at you from some Marines, and support coming at you from Marines, too. Talk about why you did the story, and what it was like.

TB: At first, I was too scared to tell the story. I initially told the Marine Corps about it as an anonymous tip. Then they told me that they didn't do anything and they just deleted it. And that's when I said, “I’ll put my reporter hat on. Let's roll."

Halfway through my investigation I went up to the Pentagon and walked in into a room with like 15 or 17 people in it. They were all high-ranking military officials, public affairs, and I basically presented them all the evidence that I had for my story, and said, "This is what my reporting will show, this is my evidence behind it. And it's time to comment." But in that room, I said, "None of this is on the record, I want every single one of you to understand what I found, because you guys are going to own this, because it's real and I'm going to prove it to you." And I did. And then, we were supposed to initially publish on a Wednesday, and the Friday before that they published a public affairs guidance, which was basically their summary of what they thought my reporting was. And their public affairs response, how they were going to answer to the media. And then we published Saturday afternoon because we didn't like that. Within four hours I was sitting in my driveway with my laptop and my wife's laptop spread out across a sheriff deputy's car, showing them, putting investigative journalism to work.

Thank you again Sheila [Coronel] for teaching me public records for finding people. I was able to find out who these people were that were sending rape and death threats, and placing bounties on images of my wife and daughter. My most recent email came in today on how I'm a disgrace to the Marine Corps and I don't understand what Semper Fidelis means. The responses were varied. It was just incredibly tense. I was like a prisoner in my own home. And my advice for journalists that deal with online doxing, or threats against their families, or online harassment for stories like this, is put your damn phone down. Put your damn phone down.

You’re not going to understand [this advice] until you get in that situation and you need to put your phone down. You feel very helpless and out of control, like you're at the disposal of the internet, which can be a very disgusting and ugly place. But in hindsight, I look at the reporting that The War Horse published. Our hypothesis was that there was pervasive sexual exploitation within the Department of Defense. By my family and I receiving rape and death threats, I think they proved my hypothesis.

BS: For someone who has been attacked and threatened earlier in their life, to then, as a journalist have these threats coming at your family, is a very challenging thing. So, if I had a hat on, it would be off to you at this moment for continuing to do it. Finbarr, you have continued to do some very cool stuff. How have you been thinking about your work, and what other kind of work have you been doing?

FO: Well, the focus of my efforts for the last four years was working on the book, but the last two completely focused on it. That has been hugely helpful and healthy for me to gain the distance and perspective from the events we write about in the book, and to put them into a broader global context. It’s allowed me to reach a point where I feel like I could pick up a camera again, and shoot pictures, because I haven't really done that for the last two years. I've been talking with people about that kind of work, but also doing some teaching and mentoring, my experience with TJ has been one where I get a great amount of satisfaction from working one-to-one, or with people who are beginning in the profession, and seeing them flourish, and do interesting things. And there are a few other opportunities that are sliding my way as a result of what we've done with the book. So, I'm looking into all of those things, and I think it'll end up being a mixture of teaching, writing, and photography as I move forward.

Audience question: I'm a marine vet as well at an MS student so my question is for you TJ. You being a Marine vet, and also going through PTSD and TBI, and coming over here. How did you handle it? How were you able to manage it, as well as being able to participate in such an intense program?

TB: I find that if I keep my mind busy, I'm actually much better off than if I leave myself sitting still. When your mind's idle it goes to places that you don't want it to, that's really how I do it.

In terms of your time here, two other things come to mind. One is that I thought you were very smart from the time you walked in the door about cultivating close relationships with mentors on the faculty. Figuring out who a few people were who got you, and whom you could talk to through the year.

My roommate was a Navy veteran, so though he hadn't seen combat, he was still somebody that had worn the uniform just like I had. We didn't see eye to eye on a lot of things, but at the same time, it was somebody who understood what it meant to serve. So, I felt a whole lot less alone. And then, Columbia has one of the most robust veteran communities, especially in the Ivy League. So that definitely helped. And then it was just keep myself busy.

BS: And I think there was a supporting role for, played by Mr. Luke, is that right?

TB: Yeah, I won a Semper Fi fund, which is a non-veteran non-profit that wound up paying for one of my dogs to be trained as a service animal, and we worked together for about two years. So, Mr. Luke helped me really get out there.

And then obviously in journalism, you're forced to talk to people. So, when I started writing, my social worker, Frank, and my psychiatrist, Dr. Webster, I love them to death. They kept pushing me, it was something that I latched onto, it forced me to talk to people, it forced me to get out of the house. I still have my bad days. I want to make that clear. I have my bad weeks and months.

Audience question: First question, how do both of you feel listening to the sounds and watching the video in front of all of us, reliving it? And the second question is directed more to TJ, but both of you can answer. You talked about one experience that was the most challenging for you and it took you three years to talk to Finbarr about it, you now talk about it seemingly a lot easier in front of a group of people. So how has writing the book changed the experience of talking about something that was initially more difficult?

FO: I think it applies to also seeing this as well as any of the experiences that we discussed, including the one that you're referring to, is that writing the book has allowed us time to process these experiences and to kind of make sense of them and position them in a way that they may feel less traumatic because they're in a context. So, one of the things that Bruce, you asked, and I meant to mention it... I think one of the reasons TJ felt comfortable after three years to tell me this particular story that we referred to is that he had been speaking with other veterans. He'd started writing a series for his newspaper about veterans of World War 2 and Korea and Vietnam, and he had learned that many of these veterans themselves had been through similar experiences and done things in combat that they weren't proud of. And he had been able to put it into a kind of historical context, and by writing the book, we've put our own experiences into a historical context, so that we have that, not quite clinical distance from it, but it feels less raw and less emotional. I don't feel any triggers with this when I watch it now, although if I haven't watched it for a long time, and I'm sitting at home, and I put the headphones on, I know my adrenaline spikes a little bit at the sound of the gunfire. But that's actually kind of a nice thing, because I miss it a little bit.

I don't know about for you when you see that stuff, when you hear it. I mean you were the one who was injured that day, I was just taking pictures. How is it for you?

TB: The first thing that stands out to me about that video is I don't think I have a Boston accent right now, and I really didn't have much of a Boston accent when I was in the Marine Corps, but that was two weeks after the explosion, and now I hadn't, the other night when we did the book launch party at the Half King. We played this for the first time and I was like, "Oh my God, I have a Boston accent, like where did that come from?" So that's what I hear when I see that, is like, "Why did I get my Boston accent back for a period of time?"

And then for the second part, it really is the distance from it.

FO: But also confronting it.

TB: Yeah. I had to confront it, and I was forced to talk about these things with my Marines, with my mental health team, with my family, with all the people that went into reporting this.

FO: And also writing about it. I remember when we were writing it, there was a lot of back and forth, and I would push you, but I would push you gently to go a little deeper on this, go a little further, tell us a little bit more about some of the things that were happening in combat. And I remember it was difficult for you to write those, but I think ultimately now you can come back and look at them with a different perspective.

TB: Well that, and I had a recent op-ed for the New York Times where I talk about how medical cannabis for veterans is something that I fully support. I wrote a good chunk of the book having been medicated. So, I mean if that helps you, that helps you, thank you, that helps you, it helps.

BS: And for the record, Thomas's op-ed in the New York Times the other day on this subject is very eloquent, evidence-based, and spot-on science.

Audience question: So, this might be a variation on the two questions that were previously asked, but can you talk about the process, how do you stare in the face of these most difficult moments of your life and not just collapse into a pile? Just the very granular process, did you decide to write early in the morning, and then go for a bike ride, or then smoke a blunt, or do whatever you were going to do? What was your process?

FO: I think these experiences aren't always great ones, but in a way, I don't think we would give them up for what we've gained having been through them. And once you've gained that experience, you want to be able to share in some sense what you've learned from them, to give them a greater sense of meaning. Otherwise they're just lost, and become nothing but your own. And if we can share a little bit, not only what happened, but what it means, and what we've learned from it, then I think those negative experiences take on a different form and a different shape.

The other part of that question is, I like to work late at night, and my most productive time of day is 9 pm til 2 am, that's my quiet, everything's dark. So, I tend to exercise, and I'll go for a bike ride for 10, 12 hours a day sometimes. And that allowed me to think a lot, it was part of my creative process, and as a friend of ours, Santiago would say, "The mind circles the wheel." And I would do some of my research with audiobooks. I'd put on memoirs that I was interested in reading, or stories about war that I was interested in reading. But I would listen to them while I rode, and make mental notes about how, what writing techniques worked, and what things I found useful, and in that sense, you could absorb a lot over time, and it was, even I may have just, the weird thing about writing is you're kind of always doing it, even when you're just lying on the couch staring at the ceiling. That's still writing in a way. It's hard to convince your friends that you're working, but. Or your mom. But yeah, I was working real hard.

BS: And what was your structure? For you, while you were working on this?

TB: I was also a night owl, because my wife at the time was working night shift at the ER, so she would be getting ready at 4:30 in the afternoon. Like I would just start getting the wheels turning inside my head, and then as soon as our daughter went to bed it was really like I'd just hop in the truck, roll up the windows, and start ticking away on the keyboard. In the evening, I like sitting out at dusk and listening to crickets come in, and I live in the middle of nowhere, so.

Audience question: Sorry if this question seems naive but, do you think after experiencing the trauma that you have reporting, and just in conflict in general, you would go back, should go back, or want to go back covering conflict?

FO: That's a good question, that's a fair question, thank you. When you've been in these places and done this kind of work, there are certain things that definitely appeal. I know for TJ the thing he misses is not necessarily the thrill of being in combat, but being around the fire pit at OP Kunjak with his boys. And for me, I miss the camaraderie of being out with my fellow journalists sometimes, even though I worked alone a lot. It is pretty great when you get out in these places and you experience really sitting on the edge of history and documenting it. And there's a thrill to that, so I miss those kinds of things.

But I think I've made a decision now that I don't want to do this kind of work, and if I do go back to covering conflict in any way it would very much be on the periphery looking at things that don't evolve. So yeah, we miss it to some degree, but I feel like I've had my run at that, and there are others who are younger and better at it then I am. So it's their turn now.

BS: And you have stayed in the military zone, but not covering conflict. Talk about that.

TB: Correct. So the one, really why I got medically retired was because when they did a QE, the bunch of crap all over your head that reads your brainwaves. They found an under-active portion on this side of my head here, which is where the blast waves came in, so it's not safe for me to be near explosions anymore, I mean for me. For me I want to go back to the fire pit with my guys. My family and their families used to send us ramen noodles, pasta, cans of pasta sauce and stuff like that. We were in the middle of nowhere. Our command couldn't see us having a fire at night. We'd sit around, and I'd be TJ, Roche would be Jim, we'd actually just be Marines, and it, for me... there's a thrill to being shot at. Anybody in this room that's been shot at knows exactly what the hell I'm talking about.

But Bruce said something to me before the Dart Awards that is, it's always meant a lot to me, the real stories matter when the trucks pull away, and when the cameras go away, and then when the reporters don't care anymore about the breaking news. That's when the real stories start coming out. And the more I pay attention to what goes on in the veteran community and how there's just a pure lack of voice and responsible journalism for the experiences we've had, and the impact that war will have on us for the rest of our lives. That's my second calling, that's my public service now. And it's also my way of, like with Marines United, like the Marine Corps is better than that, the Marine Corps a whole lot better than that. And journalism allows me, to sound cliché, to keep our honor clean. So, it allows me to continue the service that I was pulled away from involuntarily when I got blown up.

BS: Wow, I can't think of a better place to end on. Thank you for that.

Thank you both for this, for your honesty and clarity, and for this beautiful book.