Oso's Mudslide: Five Journalists Speak

On March 22, a massive mudslide washed over Oso, Washington, resulting in the deadliest landslide in United States history. As of this writing, at least 36 are confirmed dead and seven remain unaccounted for. The Dart Center spoke with five journalists about the challenges of covering the tragedy. With photos by Marcus Yam.

Faith leaders of the local ministerial association hold hands in a prayer circle before the start of the prayer service event for the communities affected Highway 530 mudslide, "Together Evening of Prayer," at Haller Middle School in Arlington, on Friday, April 4, 2014.

On March 22, a neighborhood in the rural community of Oso, Washington, an hour north of Seattle, became the site of a tragedy that was difficult to comprehend, and challenging to cover. A wall of wet earth, carrying approximately three times the volume of mud as there is concrete in the Hoover Dam, moved through a square mile area, leveling homes and burying dozens of residents. As of this writing, at least 36 are confirmed dead and seven remain unaccounted for. It is the worst landslide in American history. “The mud is up to 70 feet in some places,” said Seattle Times Metro Editor Richard Wagoner. “There may be some people that they never find.”

The Dart Center’s Ariel Ritchin spoke with Wagoner and his Seattle Times colleagues Paige Cornwell and Marcus Yam, as well as the Everett Herald’s Scott North and KIRO 7’s Natasha Chen about the reporting challenges in covering this story, including working with families of missing people, the role of social media in a time of emergency, and working through the personal challenges of chronicling trauma.

Click here to access Dart Center resources for journalists covering natural disasters.

.jpg)

Marcus Yam / Seattle Times: A mudslide on Saturday along Highway 530, near Oso, sent a huge chunk of this hill into the North Fork of the Stillaguamish River, March 22, 2014.

Ariel Ritchin: Did you have conversations in the newsroom or with your editors about how to approach this story? If so, what were the considerations?

Scott North: First off, this is a story that is of and about our community. And that is really important. These are folks that we know. These are folks that we’ll bump into in the grocery store afterward. Straight up this is the worst mass casualty incident in our county’s history. This is not tornado country. We have earthquakes, but fortunately, they haven’t been devastating. This is the worst. And it’s going to go on for a long time—we know we’re going to have to cover it over an extended period. And that we’re writing about people, real people, and they have real stories and real pain and so we’re treading carefully. And everybody’s talking: editors, reporters, photographers. What’s the right thing to do?

Our newsroom ethic for a long, long time could probably be summarized best as “It’s never the wrong time to do the right thing.” That’s not anything unusual to us but, you know, we think about the impact of our stories and take a lot of care, particularly when people are hurting.

Richard Wagoner: Like most breaking news stories, we had informal discussions early on about making sure we were reporting only accurate, verified information. This was a very chaotic event and its scope didn’t become clear for a day or two. Initially the authorities were confirming only two or three deaths and a handful of homes as involved. We tried to be careful to avoid reporting rumor or conjecture as to the extent of the casualties and damage. At the same time, we moved quickly to try to get a handle on the neighborhood that was hit to better understand the potential of the disaster. We have a lot of people on staff who have covered big breaking news stories and have dealt with people in crisis situations. They are well trained and have a lot of experience in how to be sensitive to victims.

We made a decision early on that we would not name anyone as being either deceased or missing unless we had on-the-record confirmation from an immediate family member who was in a position to know. That meant that at times we didn’t have names of some dead or missing reported by other media because we wanted to make sure we were careful. The last thing we wanted to do is to list someone as missing or deceased when they were neither.

Natasha Chen: Our discussions each day are about where we need to be. The mudslide happened in Oso, in between Arlington and Darrington. There are stories to be told on both sides, so we need crews in both places. Then there's my task, which has so far been all about finding victims' families and going to talk to them outside the slide zone. The reporters decide how to approach families. Having done this for awhile, it's assumed that we all know how to be aggressive with getting the story but being respectful to those having a hard time.

.jpg)

Marcus Yam / Seattle Times: Markings left behind by search teams could be seen on a mobile home sitting in the debris field as recovery efforts are underway, near Oso, on Tuesday, March 25, 2014.

Marcus Yam: There is always a discussion about how a newsroom approaches a breaking news story. When out in the field, my colleagues and I talk among ourselves to try to better understand what’s unfolding in front of us as well as what isn’t unfolding at the same time. We then communicate with our editors back in the newsroom, who work to piece together the bigger picture of our coverage. We are constantly communicating to discuss our priorities and to consider the best approach.

The first question we asked ourselves was simple: how can we best tell the story about the devastation and human toll caused by this natural disaster without causing more grief to those who have lost and suffered? We sought to go above and beyond the shock value of the news cycle, to try to understand why it happened and how it happened.

The first days were difficult. Information was scarce. Phone lines were out. Cell signal for certain carriers was almost nonexistent. People were emotional. My priorities, at the very least, were to be as calm and collected as possible and to best represent my newspaper.

We had to put our ears to the ground to take a pulse of the community, to better serve and gain insight. This allows us to get access to information from the perspective of the locals and to try to understand the many narratives that are going on beyond what is unfolding before the press corps.

From discussions with my editors, I understood that our coverage would evolve on a day-to-day basis, in poignant, succinct chapters. From the enormity of the devastation, daring rescue efforts, volunteerism and the pain caused by tragedy, the coverage then evolved into personal accounts of the tragedy, about building hope and coping with grief. Because I was in Darrington covering the resilient community there, our coverage focused on the people and how they have banded together to help one another and stand by each other during this tragedy. Once FEMA and the National Guardsmen took over, the coverage turned toward the recovery efforts and the complexity of the logistics behind it.

Another minor consideration was our endurance and well-being as journalists. It’s by far no comparison to the the hours the rescue workers were pulling, but my colleagues and I were working 18-hour days for TWO weeks straight. Our editors were constantly checking in on us to make sure that we did not crash and burn, and providing the necessary support we needed to continue to do the work that had to be done.

Marcus Yam / Seattle Times: Dayn Brunner, left, talks about his sister, Summer Raffo, who is still missing in the Highway 530 mudslide, and possibly trapped in a vehicle. Andrea Holm, second from left, and Josie Fanning, far right, console Brittney Smith, who is a younger sister to Brunner and Raffo, on Sunday, March 23, 2014.

AR: Is there anything you make sure to do before going to visit families of victims?

NC: I have actually been keeping an Excel file for the newsroom, of all the missing people, their family contacts, which reporters have spoken to them, whether we have pictures, etc. Our team is strong, but because we have so many reporters, it's important not to bother someone that your colleague has already spoken to. So I encourage all my fellow reporters to check the file for notes before we touch base with another family member.

SN: We’ve been careful about what we publish regarding who’s missing and who’s presumed dead and those sorts of things. Obviously, the disaster area is in a definable location and like everybody else, we pulled up the property records right away. We’ve been careful about publishing that information until people are ready to acknowledge that the person is missing or dead. I mean it’s a mass casualty incident, but it’s kind of the same approach that we would take if it was a car accident with a single family. You just have to show respect. We ask the families for permission and the honor of telling the story of the person that has been lost, and we don’t take that lightly. We accept their answer, and we always tell them, “Maybe now isn’t the time. Maybe someday it will be the time. And when you’re ready to tell us about this person, we’ll be ready to listen. Doesn’t matter how long.”

We’re getting access, you know. We’re out there and when I said, “We’re of this community,” that really does matter. There are big recognizable media outlets coming to town to cover this awful event, and many people are choosing to talk to us because they know that we are like them.

RW: We had three or four reporters assigned to try to find victims or family members of victims. We did that because there was very little information being released initially about the number of casualties or the missing. The folks who were calling family and friends of potential victims have dealt with people in crisis before, so they know how to be sensitive.

MY: My personal belief is that the only thing you can do before visiting families of victims is to be a human being. I remind myself that I am not just there to tell their story, BUT to listen to it.

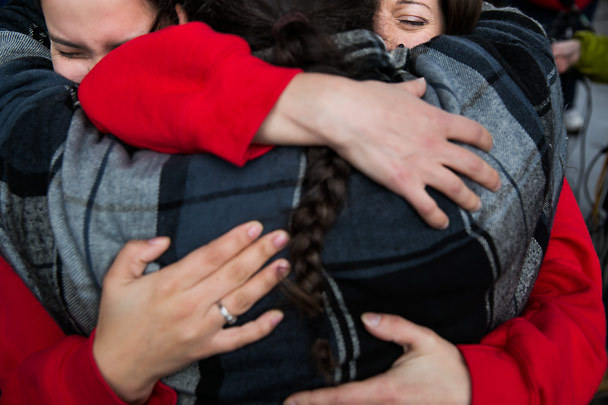

.jpg)

Marcus Yam / Seattle Times: Darrington Fire District 24 volunteer firefighters, Jeff McClelland, from left, Jan McClelland and Eric Finzimer, embrace each other after saying a prayer for the victims and survivors of the massive mudslide above the North Fork of the Stillaguamish River onto Highway 530, in Darrington, on Wednesday, March 26, 2014.

AR: Do you look to anyone or any previous work or guidelines for help in terms of how you go about telling a story like this, and in terms of self-care for your reporters?

NC: I like to watch good network reporters, the ones who really write incredible stories. I also have previous experiences to learn from. I was the first one live at Fort Hood when the army psychiatrist shot and killed 13 people. I also covered tornado recovery in Moore, OK. I learned to focus on one thing at a time, one goal, one interview. Because it's so easy to look at the scene and to get overwhelmed with trying to take everything in or chase 37 different things going on at once. I have learned to ask for help from fellow crews on the scene, ask for help from the desk, to make sure my piece gets done. I'm just one part of the puzzle my station puts together to paint this picture of what's going on.

SN: We have floods and we have mass casualty fires and we have horrible homicides that cause people to react as a community, and in that way this is familiar terrain and it’s helpful. We have protocols that are really more part of our culture in the newsroom about how we cover tragedy and loss…that’s really part of our muscle memory and we’re relying on that.

Not to toot the Dart Center’s horn, but I will. Of the things that we distributed and made sure everybody got a copy of again yesterday is the Tragedies & Journalists handbook. It’s something everybody is encouraged to read and to read again. There’s an awful lot of good practical advice there. Plus, in writing, it’s important to have really smart people saying, “You know, you’ve got to take care of yourself too.” We are right now in the middle of covering a still-unfurling breaking news story, so it’s all hands. But we’ve stood people down, we’ll dial it back. We know that we’ve got to be here for the long haul. We’re paying close attention to the impact on our reporters and photographers.

RW: We learn from every breaking news situation and try to apply those lessons to the next story. As far as self-care, we did have a conversation among editors a couple of days after the mudslide about whether any of our staff should be reminded of resources available to help them process the horrendous grief they’ve been exposed to either at the scene or in talking with victims and their families. We had a follow up conversation about that just a few days ago, as well. Access to the debris field and the recovery effort has been tightly controlled with only occasional media tours allowed in. We’ve heard many horrific stories of what recovery workers were finding, but we in large part haven’t seen what those workers have seen. Still, our staff has spent time either in person or on the phone with grief-stricken rescue workers and victims and their families, and have seen the splintered remains of what use to be a quiet neighborhood. That all takes a toll.

MY: I did not have any time to look up previous work or guidelines for help. But I have covered a few natural disasters and tragedies and I’m using what little experience I’ve gathered as operational guidelines to help carry myself in these kinds of situations.

Marcus Yam / Seattle Times: An excavator, sitting on a pile of logs placed there for stability, clear a water channel to drain out the flooded areas of the debris field in the aftermath of the Highway 530 mudslide west of Darrington, on Wednesday, April 2, 2014.

AR: How have you and your team used social media in your reporting? What steps do you take to verify content?

Paige Cornwell: Social media has been very important in how we reported the news and how we found out information. The day the mudslide happened, Snohomish County residents in some areas were being told to evacuate their homes and move to higher ground, but the locations and specific information kept changing. Using Twitter we were able to provide residents the most up-to-date, accurate information. Several agencies, including Snohomish County, the Snohomish County Sheriff's Office and the National Weather Service were tweeting, which was helpful when we were compiling information. Rather than having to call every agency, we were able to simply look at our Twitter feeds. This saved us, and the officials, a lot of time.

Using applications like Storify, I was able to find tweets and Facebook posts that referenced the mudslide. We didn't use the tweets or posts as confirmed information. Instead, we used them as a starting point.

RW: We regularly use social media both for reporting and disseminating our content. We urge our people to tweet early and often. But we also tell folks that our standards for tweeting are no different than our standards for putting something in the print editions or running something online. We don’t tweet rumor. We have a brand to protect and people expect that information we put out in what every form is vetted and verified. In this case, we also mined social media to help us write profiles of the victims and collect photos. In those cases, we mainly used social media to find sources who could help us learn more about the victims.

AR: Have you been cycling reporters in and out in a regular way?

SN: There hasn’t been one person who’s sat there for the whole duration. But, you know, it happened on a Saturday morning and we brought extra people in. It’s only Wednesday [March 26] yet it feels like a Friday… It has required a lot and we’re going to make mistakes and I’m sure we probably could make better decisions on some things. But we’re trying to think about the impact on our community and on each other as a result of this.

Marcus Yam / Seattle Times: A U.S. Coast Guard search helicopter flies over the peak of the hill where the massive mudslide above the North Fork of the Stillaguamish River onto Highway 530 occurred, west of Darrington, on Monday, March 31, 2014.

AR: I can’t help but think about the missing Malaysian Airlines Flight that dominated the news for so long, and the connection here. How does the knowledge that there are still people missing change the way you approach the assignment? Are there different angles that you’ll take just because so much is unknown?

RW: Obviously, the fact that there were so many reported missing in the mudslide, at least early on, has been a big element of the story. At one point authorities said they had 176 reports of missing people. That wasn’t 176 missing persons, but 176 reports. The truth was that most of the reports were duplicates and/or involved people who really weren’t missing. As of Friday there were 36 dead and seven missing.

I think the fact that there was so much confusion about the number of casualties and missing made it imperative that we take extreme care in how we reported those figures. We didn’t want to make the numbers sound bigger than they really were. The event was tragic enough. We worked hard to try to understand how the numbers were being collected and reported so our readers could rely on us to provide accurate information in a very confusion and emotional situation.

As to different angles on the story, one example is that we did explain why it was taking authorities so long to recover and identify the victims. We did this by not only talking to the local officials but also by reaching out to others nationally who have been involved in similar work at other mass-casualty disasters.

NC: We have to remember that these are real people, and they're buried in the mud. We want the story, but nothing is more important than being respectful of these families.

SN: What’s the terminology to use right now? What’s the appropriate way to describe what’s going on? We are just trying to talk amongst ourselves, and making sure that we have headlines that are reflective of what we know to be true. You don’t want to call someone a victim if they’re missing.

We may not know for many weeks how many people we lost in just a few minutes one Saturday morning.

Marcus Yam / Seattle Times: Rescue workers carry an inflatable boat to the flooded area in the debris field caused by the massive mudslide above the North Fork of the Stillaguamish River onto Highway 530, as recovery efforts are underway, near Oso, on Tuesday, March 25, 2014.

AR: What do you find most challenging about a story like this?

NC: Getting enough sleep, finding bathrooms in remote places, and finding food. We pull long hours when big disasters strike. I majored in psychology as an undergrad, so I'm familiar with talking to grieving people. Even so, it can wear me down after talking to a dozen families, all of whom are crying and digesting the information that their loved ones are gone. They all want someone to listen. When the story is over though, it's ok to laugh with my team and turn that sad switch off. Otherwise it's just too much.

SN: This is happening right as our newsroom is being moved into a different building. We were sold last year, and our new owners decided to move us into another space. We’re working from a place that wasn’t a newsroom until a couple weeks ago. We're sitting at folding tables, and our stuff is still in packing boxes. If you’ve covered a political convention or if you’re in an election night, imagine being in that twilight zone. And then throw in the mass casualty incident with a giant landslide and all sorts of uncertainty, five days into it.

RW: A lot of these situations are chaotic, especially early on. This one was chaotic for many days. So a huge challenge we had was accurately describing the scope of the disaster. As I said, the scene was tightly controlled and access to the rescuers was limited at times. Also, this mudslide occurred about 60 miles north of us, so several of the reporters and photographers who were initially sent to the scene ended up staying in the area for a few days without any overnight provisions. Additionally, we always look for watchdog angles to big breaking news, and this story was no different. So while we were reporting the human toll of this disaster, we were also producing stories about how this hill had slid before and about reports experts had previously issued about the potential for a big slide.

Marcus Yam / Seattle Times: Melynda Davis, Snoqualmie Tribal Deputy Secretary and Council member, from left, Alex "Kisa" Jimenez, of the Hopi Tribe, and Rhonda Neufang, Snoqualmie Tribe Council member embrace each other after a press conference in Darrington, on Friday, March 28, 2014.

MY: There are two major challenges about a story like: the emotional toll a tragedy can take and how to best put it in context for our coverage. The reporters and photographers in the field are absorbing the community’s reactions, fears and anxieties. We are also witness to the scale of the destruction and emotional reaction to it, while documenting in the debris field. We have to remind ourselves to go beyond the shock value of the story. And we have to remember to humanize it. My effectiveness depends on how well I am able to channel these emotions and not just compartmentalize them.

The one downside in the coverage of the tragedy was the sheer number of members of the media that descended into that little logging community of Darrington. Everywhere you turned was a TV cameraman and an anchor doing a stand-up. The press corps was there for every private moment. Every move was documented. There were also complaints about journalists sneaking into private meetings and reporters burning bridges with members of the community. The saturation of the news media in the town of Darrington eventually left a bad impression and made it harder to cover this story from the community’s point of view.

The challenge for me, representing my newspaper, was to stand apart from the press corps. There was a fine line between knowing when to push for information and when to pull back, in order to remain sensitive. I sometimes had to give up making impactful pictures for the sake of being respectful and gaining trust with the community. Good photographs came few and far between during my time covering this story. But it was never about the pictures. It was about telling their stories.

At the end of my two week stint, the Mayor of Darrington walked over to the pool of photographers sitting with their computers in the corner of the community center and turned his camera on us. He smiled as he took that picture. He then thanked us for our service to the community. In that moment, I smiled for the first time in those two weeks.

The most important take-away from this coverage is that as journalists, we have to be gentle, but relentless, in pursuit of public service and storytelling.

Marcus Yam / Seattle Times: A large American Flag flies at half staff in the debris field caused by the massive mudslide above the North Fork of the Stillaguamish River onto Highway 530, west of Darrington, on Wednesday, April 2, 2014.

AR: Lastly, Scott is there any advice you want to share for other journalists?

SN: There was a young reporter, a really good young reporter out of Seattle who tweeted yesterday about how surprised he was when one of the emergency management people told the reporters “There’s help. There’s an emotional damage component here and we’ve got services available for the community who are suffering in that way.” And he said the same thing to the reporters; that they might need that too. And the reporter said that he had never heard that before. And I tweeted back to him about Dart.

I think any of us that have been exposed to covering trauma and violence and that deep, deep well of sadness come to understand that if you’re going to be able to do it, and continue to do it over a period of time, you have to be smart about it and you have to take care of yourselves.

Marcus Yam / Seattle Times: Residents bow their head in prayer as they attend a prayer service dedicated to the communities affected by the Highway 530 mudslide, during the "Together Evening of Prayer" at Haller Middle School in Arlington, on Friday, April 4, 2014.