Reflections on the Murder of Mexican Photojournalist

Rubén Espinosa is the fourth Mexican journalist murdered this year. But six weeks after his killing, it is the details of his story rather than his place in the sequence of murdered colleagues that make his case especially haunting.

A freelance photojournalist who received death threats in Veracruz, Rubén Espinosa fled to the Mexican capital where he and his colleagues felt certain he would find safe haven.

His murder in Mexico City conjures for me chilling memories of death squad threats and disappearances, targeted murders, and bombings of newspaper offices when I reported on Central America some 30 years ago. In those years of civil war, military-backed authoritarian regimes controlling El Salvador and Guatemala silenced journalists who dared to ask questions. Espinosa’s murder is alarming for reasons beyond simple déjà vu. Mexico was considered a safe haven for refugees, and a country whose daring, intellectually sophisticated and vibrantly opinionated press was the envy of Central American journalists. Those of us who follow events in Mexico have seen the space for pubic debate shrink to the point of disappearance in one region or another. But our image of the nation’s capital may have led to a dangerous denial.

If we are honest those of us who follow Mexico know that for more than a decade democracy there has been losing ground. As Alma Guillermoprieto points out in Mexico: The War on Journalists: Espinosa’s murder upped the ante and the terror felt even by those reporters who have been chronicling these horrors for years from the relative safety of the Mexican capital. And at the same time Espinosa’s murder provoked unprecedented condemnation by journalists, writers, academics, and artists from more than forty countries.

One may see this outcry as reason for hope. Yet, as Francisco Goldman points out in his New Yorker post, the prosecution’s investigation has seemed by turns ill conceived and deliberately obtuse in its refusal to examine obvious lines of inquiry. Carlos Lauria, the senior program director for the Americas at the Committee to Protect Journalists recently told Sin Embargo that the assaults on the Mexican press are “a problem of democracy not a problem of journalists.”

Photographs by Rubén Espinosa from Espinosafoto Instagram.

To better understand the situation Mexican journalists face, the Dart Center asked two Dart Ochberg fellows who work in the area of press freedom, Marcela Turati and Javier Garza, for their perspectives:

Donna De Cesare: If you could name just one specific issue what would you say is the biggest challenge the press faces in Mexico today?

Marcela Turati: There are a number of challenges facing us during these desperate times in Mexico. Foremost is the very real battle against impunity for crimes against journalists. Such crimes are not punished, allowing those who would silence us to believe that they can keep killing or threatening journalists. This is why the murders of journalists don't stop, but instead continue to increase. Another aspect is the reduction of critical spaces. The independent media, the most credible voices, are being silenced by those in power. There are fewer and fewer places to practice journalism and it is increasingly difficult to do so, both because it is so dangerous and because of economic cuts and worsening labor standards.

Javier Garza: Impunity. The inability of Mexican authorities at every level (local and federal) to investigate, prosecute and punish attacks against journalists is the main engine pushing new attacks. Any potential aggressor thinking about beating, threatening, spying, kidnapping or murdering a journalist for his/her reporting knows he/she can get away with it because most of those who did it before were never punished.

More than 90% of attacks against journalists in Mexico go unpunished and this has made it safer for anyone who wants to silence reporters to engage in violence against the media. Even with new laws in place that federalized crimes against the press, established a special prosecutor and created a federal protection mechanism, violence against the media is rising, which means that the institutional response has not worked. One year ago, when the current legal mechanisms did not exist, Freedom House ranked Mexico as “Partly Free” in its world report. Today the same report ranks Mexico “Not Free”. How can we be worse off now with special “protections” than we were before they existed?

Donna De Cesare: The response to the murder of Rubén Espinosa was rapid and dramatic. Why did his murder provoke such a strong reaction in Mexico and around the world?

Marcela Turati: Rubén was an exiled journalist who was murdered in Mexico City. He publicized his situation in the media thinking it would give him protection. He notified all the press freedom and defense organizations; the government was also informed about his case. He shouted out in every possible way that he was threatened, but still he was killed. It is the first recent murder of a journalist who had taken refuge in Mexico City. It's a chilling message for us all.

Javier Garza: According to the website www.periodistasenriesgo.com (hosted by the International Center for Journalists and Freedom House, and where I collaborate) seven journalists have been killed in Mexico in 2015, though in some cases a professional motive has not yet been determined. This is also a problem when authorities investigate the murder of journalists. They are quick to discard the possibility that the crime is linked to the victim’s work. This is another reason Rubén’s death provoked so much outrage, because the Mexico City attorney general dismissed the hypothesis in less than two days that the murders were linked to Rubén’s work. Many journalists and activists (myself included) didn't think the authorities had taken the history of threats against Rubén seriously or considered them to be a major factor in the crime.

But the main reason this case got so much attention is that it happened in Mexico City, where no journalist had been killed in 30 years. (The last one was the political columnist Manuel Buendia in 1984, perhaps the most famous murder of a journalist in the country). We have thought of Mexico City as a haven, a refuge, where journalists from all over the country could escape the threats they faced in their cities or regions. Rubén fled to Mexico City precisely for this reason; because of threats in Veracruz, the most dangerous state in Mexico for journalists. Because one of their own had been killed in the capital, journalists felt that a layer of protection was gone. And because journalists in Mexico City work in news organizations with the widest audience, this case became more prominent.

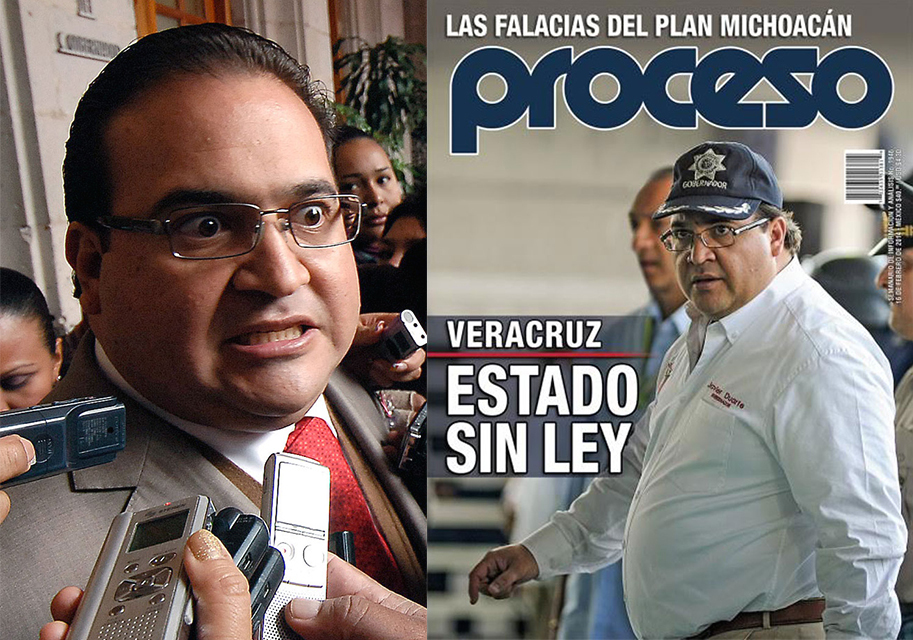

Photograph © Rubén Espinosa / Cuartoscuro; Photograph 2 courtesy Revista Proceso/Rubén Espinosa: Espinosa's portraits of the governor of Veracruz, Javier Duarte in Cuartoscuro and on the cover of Revista Proceso are the kind of news photographs that routinely grace the covers and opinion pages of Western magazines. According to the Mexican online investigative publication Sin Embargo, Espinosa was subjected to a pattern of stepped up surveillance by the regime in Xalapa as well as efforts to exclude and isolate him and to prevent circulation of Proceso after the cover story ran.

Donna De Cesare: Photographers have been killed before in Mexico but Rubén’s murder is the first to have received such an immediate and broad based response. What is the significance of this for Mexico’s photojournalists? Journalism at large?

Marcela Turati: It is interesting. In 2013 Rubén traveled to Mexico City to seek psychological help (I do not know if he received any) and to denounce the threats facing journalists in Veracruz. He arrived just when a group of photojournalism advocates had called a meeting to organize the group Fotoreporteros MX to protect themselves. They felt they needed this kind of protection because many photographers in Mexico City had been brutally beaten by police while covering demonstrations. Rubén told them about what was happening in Veracruz and the photojournalists decided to demonstrate in the streets with an image of a blindfolded Veracruz. Last year the photographers held an auction of their work to raise funds to support the family of Veracruz colleague, Gregorio Jimenez, a photojournalist whose murder investigation stalled. Their efforts raised more than funds; they raised awareness of Jimenez's case and sparked a movement of international solidarity.

I think Rubén’s murder has made a significant impact because it happened in Mexico City; because he joins the growing list of those journalists killed who worked in Veracruz; because he was personally known to many journalists and photographers, and even those who didn't know him were aware of the threats he’d faced and his forced displacement. He was interviewed widely, denouncing his situation, and was seen as a leader in the community of Veracruz reporters who are seeking justice for crimes against their colleagues. All of these factors led to the level of international solidarity we are now seeing. Veracruz reporters have told us that they feel shielded by the international attention that this case has received. That is perhaps a good thing, but I still don't see evidence that changes have been made in terms of real protection for journalists in Veracruz or elsewhere.

Javier Garza: I think it made no difference that Rubén was a photojournalist. Had he been a reporter with the same circumstances the case would have gotten the same level of attention. However, it is significant that he was a photojournalist because they are the most vulnerable -- the weakest link in a newsroom. Rubén was also a freelancer, so he didn't have any built-in institutional support. He was at a clear disadvantage, so this case could be a turning point in the way we look at attacks against journalists in Mexico. I think the response could become a model for how journalists should react to future cases. Because, unfortunately, there will be future cases.

Donna De Cesare: Some time is passed since Rubén’s death and we all know that cold cases result from a lack of vigorous investigation at the outset and from diminishing media attention and public pressure. Do you have any reason to feel hopeful that this case might be solved?

Marcela Turati: The more we see the way this case is evolving -- full of lies, leaks, re-victimization of victims, and crafty management of records -- the more we realize that they're not really investigating the threats that Rubén had received as a potential motive. It is hard to see how this case will be solved. This, despite the fact that there is a lot of pressure and a lot of people watching, insisting that the case be investigated well. If the Mexico City prosecuting attorney does not reorient the line of investigation, it will become another crime that remains unresolved and unpunished.

Javier Garza: I think the main unanswered question is why a journalistic motive was not thoroughly considered in the hours after the murder. There is the possibility that the murder had nothing to do with Rubén; that he was in the wrong place at the wrong time, but that would be an incredible coincidence. There are questions about the people who have been arrested and their statements. I think the case will be “solved” by pointing to the “Colombian connection” (the hypothesis that one of the victims, a Colombian woman, was linked to drug dealers). But I believe that we will never know for sure how seriously the authorities took Espinosa’s situation (i.e. the previous threats, his “exile”) as a factor.

Donna De Cesare: You are both Dart Ochberg fellows with extensive personal experience dealing with these kinds of pressures and violence that Mexican journalists face. What are some things that journalists outside of Mexico can do to help our colleagues going forward in this critical time?

Marcela Turati: The first thing is to research and publish stories about the murders of journalists in Mexico. Investigative journalism has impact. There must be systematic and timely follow-up in the international media. We in Mexico know that the only thing that makes our government respond is international criticism.

In addition to international solidarity and keeping these issues in the headlines and on the press agenda, there is an urgent need to establish a fund for threatened journalists. Psychological help is urgently needed; a house of refuge where journalists at risk, their families and children can take a break and plan what to do next while in a place of safety. We need scholarship funds for journalists who have been forced to flee so that they can continue to investigate the stories that those who threaten them want silenced. And, finally, we need institutional support so that we can continue to work to empower local reporters who are the most vulnerable.

Javier Garza: I think that foreign journalists can help by keeping the story of violence against the media alive. Not just Rubén’s murder, but also the other homicides that have gone unnoticed because they took place far from the capital. They form a pattern that has extended for a decade, but it is shifting. Five years ago the focus of violence against the press, especially extreme violence like murder and kidnapping, was in the Northern states (Chihuahua, Tamaulipas, Sinaloa, Coahuila, Durango). Now the hot spots are in the South, mainly in Veracruz.

Of the seven murders documented by www.periodistasenriesgo.com in 2015, six have been in Southern states (Rubén Espinosa is the exception). Three have been in Oaxaca, two more have been in Veracruz and one more in Tabasco. But like Espinosa’s case, another of the victims, one of those killed in Oaxaca had actually been working in Veracruz, so this state is clearly connected to the murder of journalists even outside its borders. And aside from the number of murders, there are scores of other types of aggressions against journalists (beatings, threats, hacking, legal harassment, etc.) that go underreported because they happen in places that receive little attention.

I think this is a story worth telling beyond Mexico. The foreign press was very helpful in telling the outside world about the murder or kidnapping of reporters in the Northern states near the US border several years ago. I think the same could be done now. Some news organizations, like El País, are keeping a close eye on this trend. Coverage in the foreign press can reassure Mexican journalists that we are not alone.