Trapped in Mexico

This investigation and multimedia project examines the Trump administration’s 'Remain in Mexico’ policy and its impacts, including the profound mental health effects on people seeking asylum in the U.S. Judges described “Trapped in Mexico” as a "staggering reporting feat" that "balances insightful data with expansive visuals and hard-hitting reporting.” Judges commented on the “unique sensitivity” of the video stories, and applauded the “slow pace of the storytelling, which mirrors the slow pace of the subjects' asylum cases.” Originally published by Univision News Digital on November 19, 2020. En Español.

The trauma of seeking asylum in the U.S. during the Trump era

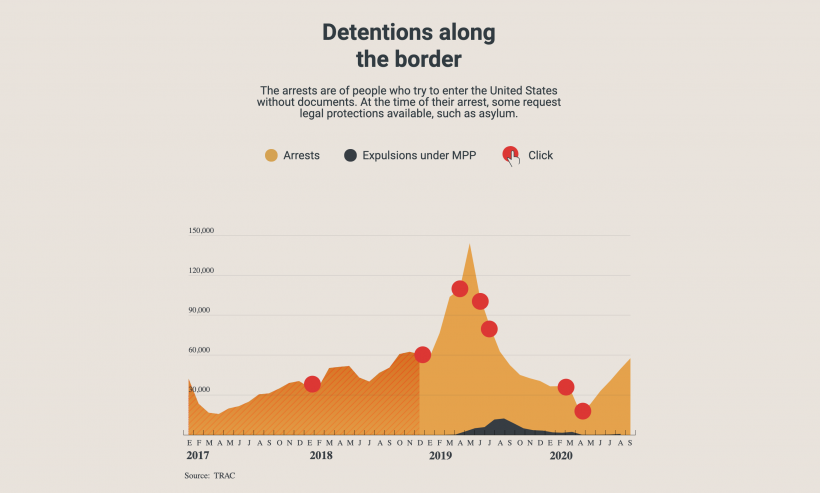

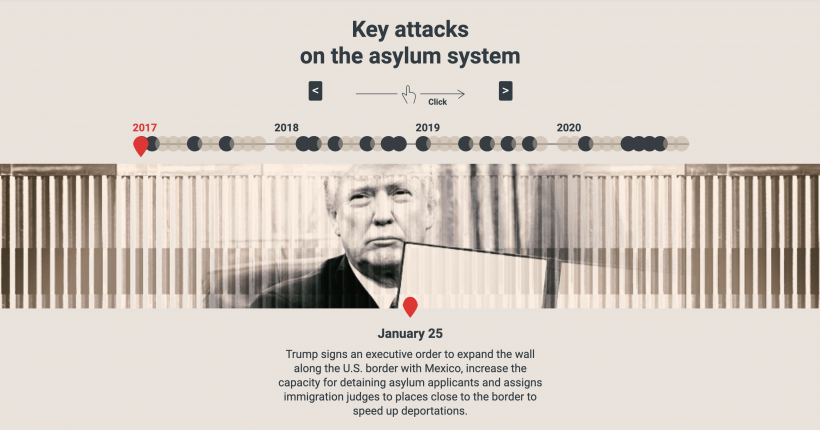

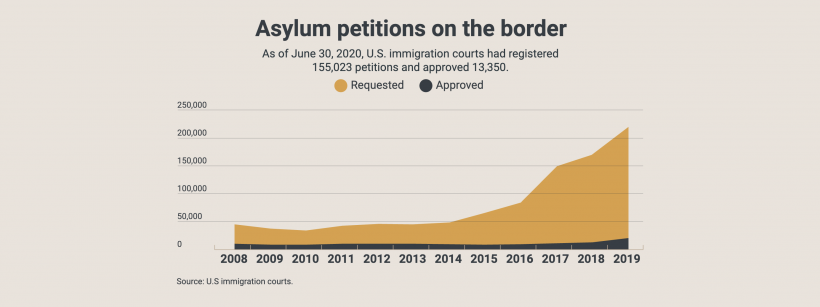

In January of 2019 and in violation of laws, agreements and regulations, the U.S. government established the Migrant Protection Protocols, a policy that forces asylum applicants to wait for their cases in the most dangerous Mexican cities on the U.S. border. The policy, still in place, reinforces the legacy of fear and trauma instilled in Donald Trump’s administration. In his four years in office and without congressional approval, he has destroyed immigration policies built by the last nine presidents.

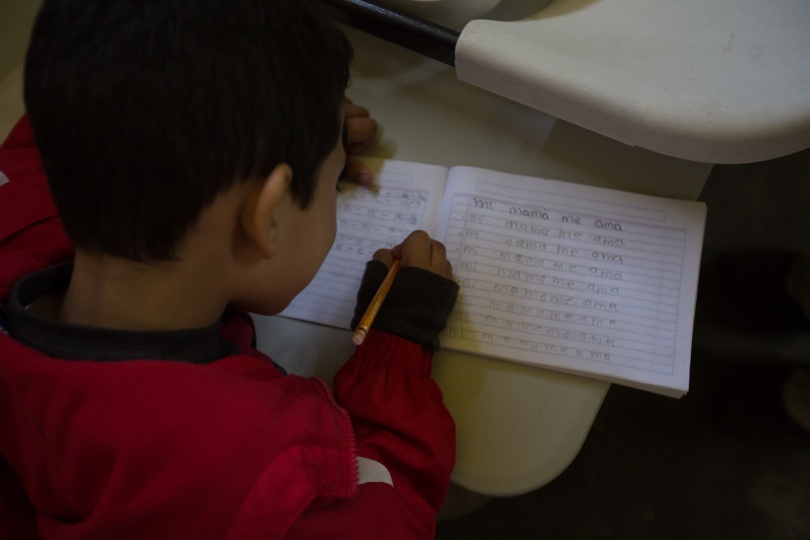

Armando, a 10-year-old Honduran boy, sits before an immigration official in Brownsville, Texas. He tells the official he and his father were kidnapped twice in Mexico. One time in Villahermosa, in the state of Tabasco. Men who said they were policemen turned them over to criminals, who stole everything they had and let them go.

The second time was in Monterrey, in Nuevo León. A hooded man put the barrel of an assault rifle to his head and a cell phone to his ear to ask his mother in Houston to pay the $5,000 ransom. Meanwhile, they tortured his father in front of him.

“He told the official it was something he would never forget. An adult is accustomed to seeing that, but a child … He couldn't see a Mexican policeman without fear. He would shake. It was traumatic,” said Armando's 37-year-old father, Damián.*

Damián and his son ran away from San Lorenzo, a community more than 100 miles south of Tegucigalpa, in June 2019. He left to avoid reprisals from gang members after he refused to hand over his son to sell drugs on the street. He also dreamed of applying for asylum in the United States and reuniting with his wife and their baby girl, who was just 18 months old when mother and daughter fled the same violence three years ago.

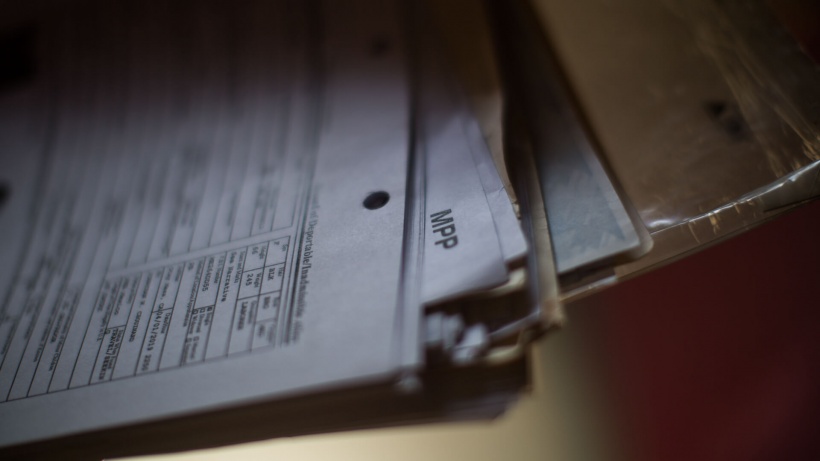

But the road to a reunion would not be quick or simple. On Aug. 18 2019, after the two kidnappings, they crossed the Rio Grande with the help of smugglers. Waiting for them on the other side were the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP).

“When we were going to cross, we were walking through the woods and my son saw a huge U.S. flag and he told me, 'Daddy, that's Texas. That's where my little sister is.' But they told us, 'No, you're going back again, you're going to Mexico.' He was very disappointed. It was very traumatic.”

Clothes lost by migrants during their crossing of the Rio Grande.

Nearly 70,000 others have been returned to Mexico, like Damián and Armando, without any protection for their rights. They were left homeless, in makeshift campgrounds, on the street or in shelters that receive no assistance at all from the Mexican government.

In the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic, the migrants are still being expelled to the other side of the wall. With the presidential election almost here, asylum seekers are hoping for a reopening of the border and the repair of an immigration system build over 50 years of both Republican and Democratic governments – and destroyed by Trump through executive orders in barely four years.

—

The MPP were put into effect in January 2019, during the administration of then-Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen, who portrayed them as a way to stop “the immigration crisis on the border.”

During the previous months, more than 60,000 migrants, most of them Central Americans, had surrendered voluntarily to the Border Patrol – an unprecedented move.

Migrants who reached the U.S. side of the border and could show in an interview that they had a “credible fear of persecution” were detained for a period and then free while a judge considered their case. But the process went forward while they remained in U.S. territory.

That all ended Jan. 24 2019, when Nielsen wrote a memo directing that all Salvadorans, Hondurans and Guatemalans – with the exception of unaccompanied minors, pregnant women and people with pre-existing conditions – who wanted to obtain asylum should remain in Mexico for the duration of their legal process, which could be months and even years.

When they were scheduled for an immigration court appearance, they were to show up at a border crossing and remain in the custody of U.S. officials. At the end of the day, most of them were to be returned to Mexico to wait for their next court date.

“Aliens trying to game the system to get into our country illegally will no longer be able to disappear into the United States, where many skip their court dates. Instead, they will wait for an immigration court decision while they are in Mexico” Nielsen declared. “‘Catch and release' will be replaced by 'catch and return.'”

The Trump administration, in an unprecedented shift, put the Nielsen memo into effect and continued to demolish the asylum system. That was the way it tried to close what it viewed as a “legal loophole” in the system. It was part of the wall against migrants thrown up under pressure from Stephen Miller, a White House aide and architect of Trump's immigration policies.

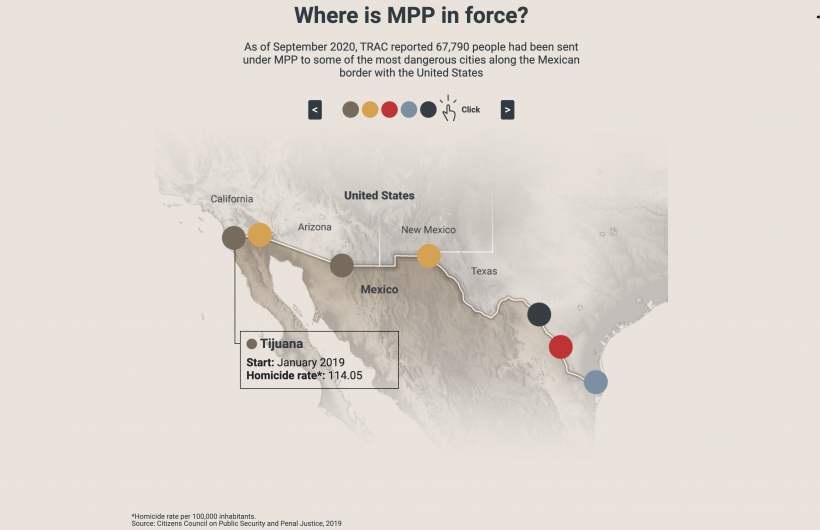

With the MPP in force, the Central Americans were left in limbo, waiting in border cities with high crime rates. The first city where it was applied was Tijuana, in Baja California.

In August 2019, the morgue in Tijuana was overwhelmed. It was receiving 15 to 40 bodies per day, bodies with 30 or 40 gunshots, with fractured skulls, strangled or beheaded. During that period, the number of victims shot dead and then dismembered rose by up to 50 percent, according to Cesar Gonzalez Vaca, head of the Forensic Medical Service in Baja California.

Arrests for use and sale of drugs in Tijuana in August 2019.

Three criminal groups were fighting for control of street sales of drugs like crystal meth in the area: the brothers Arellano Félix cartel; the Sinaloa cartel; and the Jalisco Nueva Generación.

“Tijuana went from being a supplier to a consumer of drugs as well. That's the problem we have right now. Ninety percent of the victims are linked to drug trafficking,” said Tijuana Police Chief Ricardo Guerrero. “They fight in the streets, on the corners, where they sell.”

And the violence is not only against the drug sellers, but against consumers as well. “If you go and buy from the guy in the corner, who's from the other side, well you're attacked too because you did not buy from them. It is a super complex problem.”

A seizure of crystal meth in Tijuana. The police arrested a young man in the street carrying the sports bag.

Guerrero explained that's how migrants in Tijuana wind up “as victims” of people smugglers and drug sellers who also could offer them jobs.

That's the broad outline of the brutal violence lashing most of the places where the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has applied the MPP. They are places where the U.S. Department of States sometimes even warns against travel there.

And Tijuana, ranked as the world's most violent city in 2018 by the Citizens Council on Public Security and Penal Justice, was considered the safest city among the seven where migrants were sent under MPP.

That's where two Honduran teenagers who traveled with one of the so-called migrant caravans were beaten, strangled and tortured to death by local criminals. Authorities found their naked bodies on this street, wrapped in bedsheets, the night of Dec. 15 of that year.

Little by little, DHS began expanding the MPP to almost anyone who applied for asylum, not just Central Americans. It added Venezuelans, Nicaraguans, Cubans, Brazilian, Colombians, some Africans and even some Mexicans (who represent 0.14 percent of the total). It reached agreements later with El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala to receive some of the returned asylum applicants – even though most of the migrants seeking protection in the United States came precisely from those three countries, long buffeted by gang violence and poverty.

Little by little, DHS began expanding the MPP to almost anyone who applied for asylum, not just Central Americans. It added Venezuelans, Nicaraguans, Cubans, Brazilian, Colombians, some Africans and even some Mexicans (who represent 0.14 percent of the total). It reached agreements later with El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala to receive some of the returned asylum applicants – even though most of the migrants seeking protection in the United States came precisely from those three countries, long buffeted by gang violence and poverty.

That number included murders, rapes, kidnappings, tortures and thefts. And 265 were kidnappings and attempted kidnappings involving children. The real numbers are surely higher, because not all the victims dare to file official complaints.

Those crimes and the long road to asylum under MPP have generated trauma and psychological damages among the migrants.

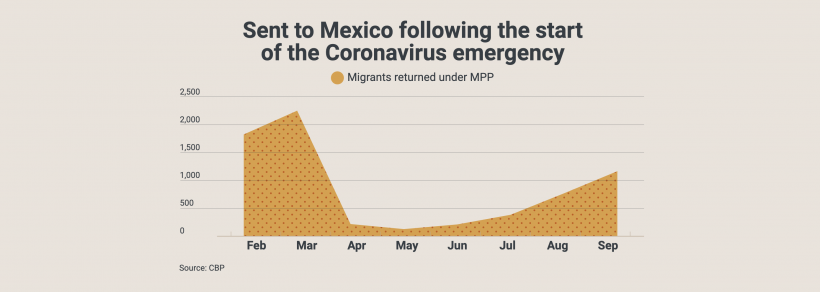

The uncertainty grew after March 2020, when the U.S. government decided to close the border because of the Coronavirus, paralyzing the court hearings for migrants waiting in Mexico. In April, there was a substantial drop in the number of migrants returned to Mexico by the Border Patrol, but the numbers spiked to 1,167 people in September, an 80 percent increase from April.

On Oct. 19 of this year, as some cities were preparing for a reopening of the border, acting DHS Secretary Chad Wolf announced an extension of the border closing until Nov. 21 because of the Coronavirus.

“With the border closed, the atmosphere here is tense, sad, and many times frustrating. Psychologically it is an irreparable damage. It is a damage that no one will ever forget. It is something that is traumatizing,” Damián said in July, shortly before the first coronavirus case was confirmed in the Matamoros campground. He had been directed to the camp, like hundreds of other migrants who depend on humanitarian assistance to live in border cities because of the MPP.

By the time the long wait at the border was made worse by the pandemic and an attempt to kidnap his son in the Matamoros campground, Damián had already made a painful decision.

Damián shows a photo of his son.

He was one of the first among hundreds of parents who accepted an option they saw as desperate but the safest for their children: They sent them to cross the border alone – defined by U.S. officials as unaccompanied alien children (UAC) – so they could be processed and reunited with relatives already in the United States. In Armando's case it was Houston, where his mother lives.

Eight parents interviewed by Univision Noticias at the migrant camp in the border of Matamoros took a desperate step. They told their small children to turn themselves in at U.S. border stations, so that they would be allowed into the United States as unaccompanied minors.

“When night came, Armando became nervous because he thought it (the kidnapping) could happen again,” Damián said. And the father could not sleep because of the strain. “I come running away from Honduras and I find a country that is the same or worse, more violent than mine. It's not easy, knowing the life of your son is in danger. Only God and my son saw how much I cried in that tent.”

Armando's encounter with the U.S. immigration official would be the beginning of an indefinite separation.

Months after Armando left, Damián knew that sending his son to the United States had been the best decision he ever made. “Now he has a little more normal life. The children here make me sad. No human being should live in these conditions,” he told Univision Noticias in July.

“Any parent you ask will tell you the same thing: that the heart winds up empty, with nothing. He was everything for me. I had to do it because I had no other option, I couldn't do anything. And maybe they (U.S. officials) don't understand that, having to be separated from the person you most love in order to save him,” he lamented in an interview with Univision Noticias shortly after he saw his son cross the border.

—

The trauma suffered by the asylum applicants under the MPP, sometimes known as “Remain in Mexico,” does not come only from the criminal violence in Tijuana, Matamoros, Nuevo Laredo or any of the other cities where it's in force. There's also the institutional violence suffered by the asylum applicants as they pass through a procedure that is improvised and has been branded as “inhumane” by immigration lawyers

like Jodi Goodwin.

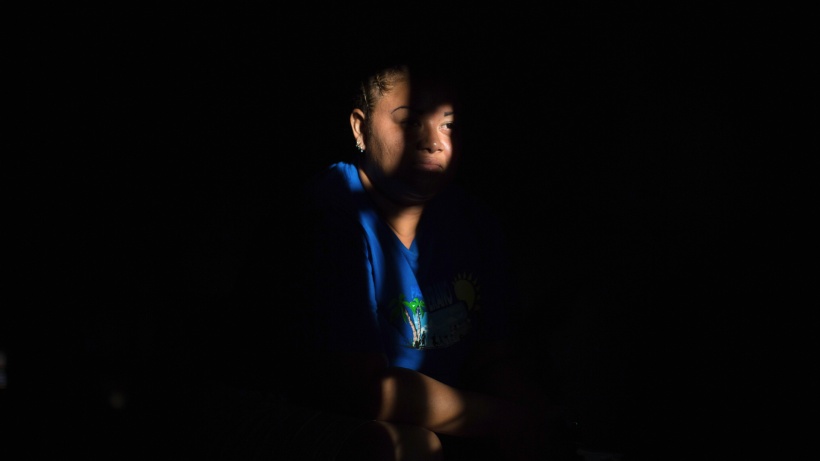

Daniela Díaz, a 20-year-old Salvadoran, spent 18 months trapped by the MPP. During that time, she developed new fears, like the fear of darkness, because the lights were never completely off during the last 10 months of her confinement in three detention centers run by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

Now back in her home after she was deported in September, she often can't sleep until 4 am. She sleeps fitfully because of her nightmares and, she says, because she needs the sleeping pills given to her by a nurse at a detention center during the last five months of her detention. Her mother tries to treat her dependence with chamomile tea. ICE officials deny they distribute such medications to detainees.

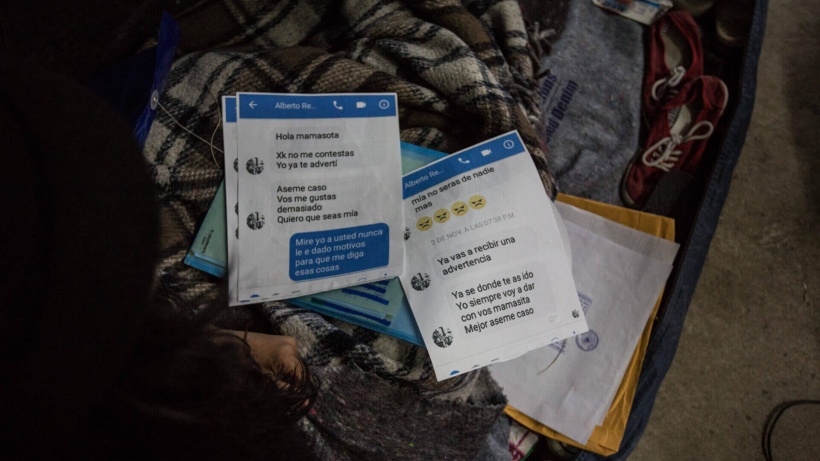

At the age of 19, Daniela had fled her country because a policeman was harassing her, even entering her home without permission to steal photos of her and threatening to rape and kill her and throw her body in a gully where it would never be found. She was also fleeing a gang member who wanted her for a girlfriend and threatened to kill her after she rejected him.

The gang member's threats against Daniela continued on Facebook after she fled El Salvador. She printed the threats to show them to a U.S. immigration judge.

In Tapachula, her first stop in Mexico, she and a girlfriend who joined her on the trip north had to run away when they encountered two gang members who knew the girlfriend from El Salvador and took several shots at them.

Gabriela, the friend of Daniela, shows one of the scars from the bullets that hit her in El Salvador after she refused to become the girlfriend of a gang member.

She hoped to win asylum in the United States, and with it the protection she did not have in her own country.

The first time Daniela applied for asylum in the United States she was detained for two days and then returned to Tijuana. Her first court appearance, in early April 2019, coincided with a ruling by a federal judge that temporarily halted the MPP, so she was held in an ICE detention center in San Diego known as a hielera, or icebox.

“We were all asking ourselves why we were taken there … until the next day, when they told me that because of a change in the law no one was going back to Tijuana.”

Tijuana-San Diego border

That day, she said, the officials told her “they didn't know what to do with us.” But in the meantime, she could not notify her family that she was detained. Another migrant recalled facing the same situation after the judge's ruling.

Daniela was freed 20 days later and was back to square one: returned to Tijuana with a piece of paper showing a new court date, a month later.

Daniela lived first in a shelter run by Movimiento Juventud 2000. She moved later with an aunt to Rosarito, more than 30 minutes from Tijuana. To attend one of her court hearings meant getting up before dawn to take a bus to the border. At times, her hearings ended at night, when she had no way to return home and had to stay overnight in the shelter where she first lived.

—

“Hello. Good afternoon. I was calling this number to see if you could accompany me to my hearing. I am going to court with a judge there in San Diego and I wanted to know if you would take my case. I am here in Mexico, waiting for the asylum process,” Daniela said into another of the answering machines she gets every time she phones the offices of an immigration lawyer.

Her hands sweat with each failed call, because she's been asked if she has an attorney at each of her court hearings. She needs one to complete her asylum application in English, and because the court case cannot move forward without a defense lawyer. That is what the immigration process requires.

“Every time I have a hearing I always call to see if someone wants to accompany me. One of them wanted to charge me just to go with me. I told him I don't have money. Other times I call and I get the same thing, that I have to leave a message, and no, they never return my call,” she lamented as she dialed more lawyers, who did not answer either. Other lawyers who have answered told her they “don't work cases in Tijuana” because they only have U.S. licenses.

The last time Daniela was detained was when she tried to appeal an asylum denial by herself, without lawyers. She spent 10 months in an ICE prison in California and two in another in Texas. In the end, she lost her case.

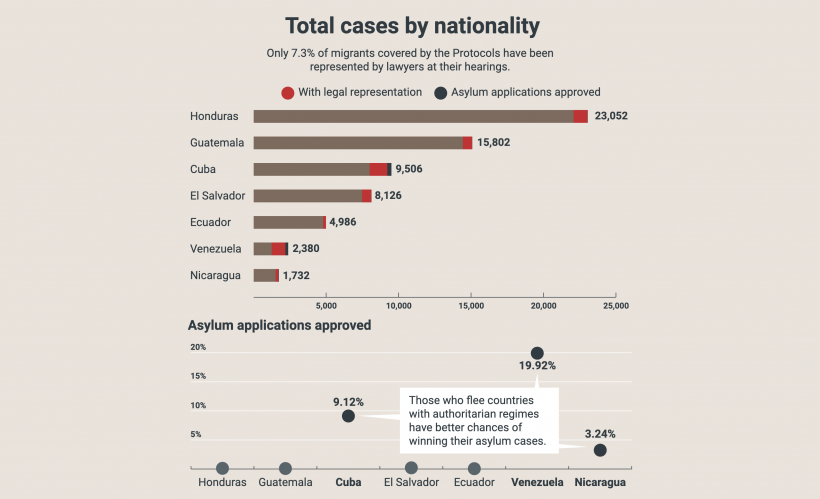

She was deported in September of this year, like nearly 50 percent of the 67,790 migrants who have been under MPP, according to an analysis by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University.

That is not a rare situation. It happens to 92.6 percent of the migrants who have been returned by the United States to Mexico to await a decision on their asylum petitions: either they can't afford to hire a private lawyer, or they cannot find one to represent them for free.

In the end, most of them lose their cases. The MPP were designed with the knowledge that they would cause these kinds of problems for the asylum applicants.

Elibet, who is from Venezuela, and her 9-, 11- and 16-year-old children, are among the 0.8 percent of migrants who have won asylum under the Trump administration’s Migrant Protection Protocols. On November 21, 2019, after four hearings in a courtroom set up in a tent in Brownsville, Texas, the judge – who appeared by video – ruled in their favor.

One of the reasons is that she and her children had a lawyer at their final hearing. Richard Newman left his job as an ICE attorney after the separation of the children and parents along the border, and joined a non-government agency to help represent asylum applicants.

The other is that her case met one of the grounds for asylum, because her family was persecuted by government officials aligned with the Maduro regime.

Elibet had left her country on June 28, two weeks after her husband was arrested by police in Monagas, a city in eastern Venezuela ruled by a chavista governor. Elibet’s husband was charged with theft of copper, a strategic material, and sentenced to 30 years in prison.

She insists that the charges were false. “He says that when they arrested him they spread copper material in his belongings, and he had nothing to do with that…That is what they are charging him with.”

They had been expecting something of the sort. She and her husband were active in an opposition party, contributing money and participating in street protests against the socialist government. In addition, in 2013 she agreed to serve as voting center coordinator in her district, where she says she saw “a great many irregularities,” such as state government workers who were threatened with being fired if they did not vote for Maduro. The couple’s high profile as dissidents made them a target for armed officials’ threats against them in their own home. Later, forensic police investigators suddenly showed up at her business and searched it without a warrant.

“They turned everything upside down…They threatened us, told us that we should quit opposing the government system, that this was treason to the fatherland,” she recalls.

“We were very afraid.”

They have now found safety with friends in the U.S. But their experience with the Migrant Protection Protocols adds to her worst memories. In Matamoros, having heard about migrants being kidnapped, Elibet was terrified, refusing even to leave their tent. “We couldn’t bathe, couldn’t go out to buy food. I felt really depressed, really disturbed. I couldn’t fall asleep, because I was thinking that if I did, that I wouldn’t have a child next to me when I woke up.”

That fear forced her into pushing her family into crossing the river “even despite all the danger,” she says. “These were tough, desperate times. To tell you the truth, I asked God’s forgiveness then for having put my children into this situation,” she says, unable to hold back her tears, because she almost drowned during the crossing.

But their arrival on the other side was futile, because they were sent back to Matamoros. “After we got to the other side, risking our lives, fleeing because we feared kidnapping, fleeing my country because we had been traumatized, and thinking that finally we would be all right… they sent us back again. I can’t tell you how crushed we were.”

Over the course of the whole process, they spent slightly more than five months on the Mexican side.

—

Immigration lawyer Jodi Goodwin says that she has experienced more crises on the border during the four years of the Trump administration than in her entire 25-year

legal career.

In January, 2019, Goodwin began to monitor what was going on with MPP in Tijuana.

“We know that it would be coming here sooner or later,” she recalls. At that time, she had been going to Matamoros once a week to provide legal orientation to migrants who planned to apply for asylum when the process took place in the United States.

But the MPP kept expanding. In July, the streets on the Mexican side of the international bridge in Matamoros began to fill up with asylum applicants whom the U.S. government had sent back. Goodwin was the lawyer who responded.

She started to make two or three trips a week. “I tried to give a legal orientation and 300 people would show up. The next week, those 300 became 400, and then 600, and then 700,” she recalls. Overwhelmed, she asked for help on social media, explaining to her fellow attorneys that asylum applicants whose cases had in the past been transferred to Boston or Chicago were now trapped in Matamoros. “Who will help me?,” she asked on Facebook. Ten lawyers joined her the following weekend.

They consulted with migrants in a public square, taking notes on paper in 90-degree heat. “I never thought that after 25 years, I would be practicing law in the streets, sweating. It’s not luxury work, but it’s important work.”

Then, in a volunteer initiative, Lawyers for Good Government (L4GG) set up a pilot program in August, 2019. Project Corazón enabled lawyers to deal with migrants remotely. After entering their personal information on a form, along with their court dates and their WhatsApp numbers, they were contacted by volunteers who listened to their accounts. When these met legal standards for asylum, the migrants got help in filling out asylum applications in English for presentation to a judge at their

next hearing.

Under this system, migrants got personalized legal advice without the lawyers having to spend money or travel to the state of Tamaulipas.

The Trump administration installed these white tents in Brownsville to allow migrants to appear before immigration judges using video-conferences

But this wasn’t the case for everywhere on the border. “Lawyers don’t want to take a case because it’s in Brownsville, in the tents,” Goodwin says. “They don’t want to travel here to go to court. So it’s difficult. In fact, the percentage of people who get legal advice or representation in court is very low.”

Maricela Amezola is an immigration lawyer in San Diego and does not take MPP cases in Tijuana for several reasons. Visiting clients or notifying them of their court dates is very difficult. Because they go from one shelter to another, “they don’t have a stable address.” Some have relatives in the United States who can pay for a consultation, but others do not. Above all, in many instances, “it turns out they don’t have a case”, because neither domestic nor gang violence meets the legal standard for asylum. Finally, many migrants, having become desperate, cross the border illegally, are detained and then face federal charges under the zero tolerance policy.

In Goodwin’s view, the MPP are a “a way to close the border…And it is working: It is causing very inhumane conditions for people waiting for their hearings.

But, more than that, it is ending due-process protections in the courts, it is eliminating everything about the right to access to an attorney. There are not many lawyers ready to go to a Security Level Four zone.”

In addition, Goodwin says, the number of people going back to Mexico “would overwhelm the capacity of the best system we might be able to create. We need more personnel, more administrative help, more technology, more time and, above all, we need a justice system that observes due process. That is what is completely missing from the MPP process.”

Migrants from the Matamoros camp wash clothing and utensils on the bank of the Rio Grande.

Since the Protocols took effect at this part of the border, the lawyer has seen U.S. officials sent back to Mexico even people exempted by the government: children, babies with Down Syndrome; pregnant women in labor who are sent to hospitals until their pain eases so that they can be returned to Mexico to give birth on that side of the border.

“My mind isn’t able to see any way that it is right to make another human being suffer. That is exactly what they are doing with this program. Those people who support the program say or believe that they are people with values, or Christians. They are not, they are not. A Christian doesn’t make another person suffer on purpose.”

—

When Michael Benavides came to the United States in the ‘90s after fighting in the Persian Gulf War, anxiety and nervous stress from memories of bombing and explosions made him grind his teeth at night, and left him unable to sleep. By day, looking at himself in the mirror, he saw a desperate person. “I couldn’t hide it,” he says. “I knew that I needed help, and I got a lot of help” because he was a veteran.

Three decades later, he sees the same sadness and anguish on the faces of migrants in Matamoros that he had once seen in the mirror. He sees it in every man, woman and child – ready for the worst, permanently on alert for any strange movement, fearful of any sound, which they immediately associate with gunfire. “This is the worst I have seen in my life, and I have been in wars,” he says. “This is worse.”

He visited there almost every day to bring food on behalf of his organization, Team Brownsville, until the Coronavirus hit and the National Guard limited access.

What the migrants are experiencing is PTSD (Post-traumatic stress disorder). “They have seen a lot of things that a child should not see. We have seen so many cases of abuse, of mistreatment, and these children have suffered a lot.” But he got help from specialists in identifying and overcoming his PTSD, while those on the Mexican border have to deal with their demons by themselves.

“This trauma is real…It can cause a lot of harm if it isn’t treated correctly. I know very well what PTSD is; they don’t.”

Benavides says he is disturbed by the cruelty of the immigration system that Trump and his advisers have fashioned. “It is sad and it breaks my heart,” he says. “This is not the America that I know.” For him, the measures being taken are tinged with “evil,” “racism,” and “hate.” He believes that this adds to the migrants’ suffering, on top of the desperation of “not having a country” to go to. In the end, he says, this is “solidifying trauma

and despair.”

So when he goes to the camp to bring food, he does it as an “act of patriotism” greater than when he went to war. “On this bridge, as everyone knows, no one is going to go hungry. Maybe they will get cold, have to pass legal tests, but no one will go hungry,” the ex-soldier says.

Benavides’ diagnosis, based on his personal experience, is not mistaken. Nora Valdivia, mental health supervisor for Doctors Without Borders, the only organization providing mental health services in the area, also sees the violence to which the migrants have been exposed as leading to post-traumatic stress. In addition are the worry and anxiety about whether there is food for the kids, or what will happen in three months when their next court date is.

To all of that, add the sadness and depression, even in children, which shows up as extreme behavior. They may become very aggressive, or very withdrawn. They lose their appetite and have trouble sleeping. “The child isn’t the happy one we used to see…These are the consequences of the changes in his surroundings, of the context in which he is now living.”

Experts say that the pandemic has deepened the limbo in which those affected by the MPP are living. Some migrants have given up. They accepted rides on buses that the Mexican government provided to transport them from the southern border and back to their countries.

—

Armando is in Houston with his mother. But memories of his journey to the United States and of the wait in Mexico remain with him. Damián, his father, says that the boy is seeing a psychologist “because he never forgets what he lived through there, in that refugee camp.”

Those who stayed in Matamoros, he says, remain affected by sorrow and frustration. “There are mothers who gave birth in tents, and others who lost the babies they were expecting, and add to this the threats by the criminals there,” Damián said in July. “You can see that there are fewer people, and the sadness in the eyes of those people every time they are told that the courts are closed and the delays go on…This is harm that no one here will ever forget.”

In his case, after three hearings, the judge denied him asylum on the grounds that he should have applied first in the other countries through which he had traveled. He appealed, and was scheduled for a hearing in June, but then court sessions were postponed indefinitely.

He says that he doesn’t fear the extortions or the kidnappings he lived through in Honduras. His only fear: That one day he could be detained and deported for lack of

legal status.

Daniela, the Salvadoran who was deported in September, does not want to go back to the United States. “I went through things I never imagined,” she says. She talks about the fear, the cold temperature of detention cells, the shackles on her hands and feet, the times she wasn’t given sanitary napkins and ended up with menstrual blood staining her body. For her, the Migrant Protection Protocols are “the toughest” experiences she has gone through in her 19 years. She held on despite her doubts. But after realizing that the process was being dragged out, she felt that suffering all that trauma wasn’t worth it.

Finally, after the threats she received in her home country from a policeman and a gang member, the insults she heard in Tijuana, the shots she heard outside the shelter, and the offers she got in the street to prostitute herself, she made her decision. For now, she prefers not to leave the house.

On Oct. 19 of this year, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to review the legality of the program, which has been challenged by major human-rights organizations in several U.S. courts. The fate of the MPP will be known in 2021. Whoever wins the 2020 presidential election will inherit an immigration policy that uses trauma as a tool.