Case Closed

You're focusing on the negative

By Rachel Dissell and Andrea Simakis • Originally published September 29, 2019

Nearly two years after Sandi and Gabe first made the trek to Cleveland’s downtown Justice Center, they once again rode the stale-smelling elevator to the sex crimes unit on the sixth floor.

Detective Evans greeted the couple kindly at 8 in the morning on June 14, 2017, but Sandi sensed an underlying tension, as if they were uninvited guests.

They settled at a table. Doors slammed around them. Keys jangled.

“It’s hard to talk right now,” Sandi said, her voice wobbly and unsure. “We have some questions.”

Sandi was nervous about confronting Evans. When she discovered her rapist’s full name, she didn’t tell anyone for weeks. Not Gabe. Not her sisters. Not Kate Biddle, the new therapist she’d started seeing. The knowledge terrified her. It overwhelmed her.

Sandi's memories flooded back after she located her rapist, paralyzing her. She didn't tell anyone.

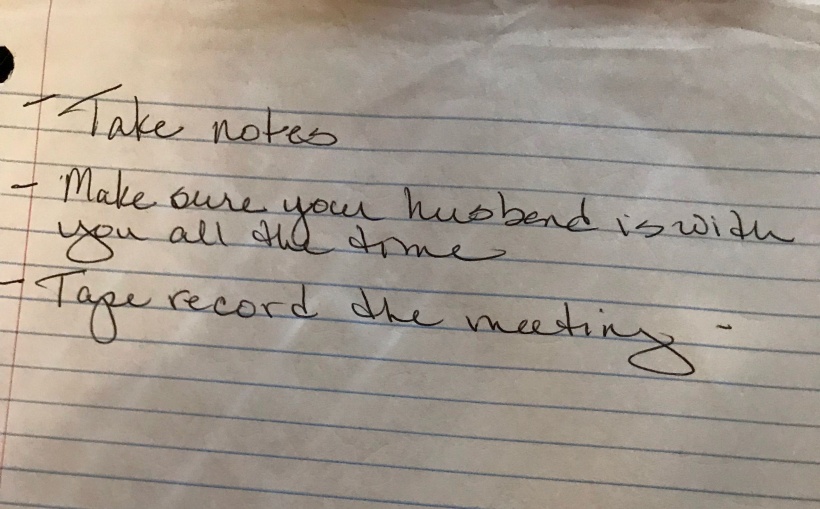

Notes Sandi's therapist helped her make before Sandi and Gabe met with Detective Evans.

Kate knew the meeting would upset Sandi and that it would be hard to remember all the details, so she suggested Sandi and Gabe record the conversation.

Sandi unzipped a black bag dotted with stemmed cherries. It bulged with notebooks filled with reminders and memories, court documents and medical records from her rape and her recent surgery. Doctors had to re-break her nose, and it was still tender.

She pulled out a folder. The computer printouts inside were from the prison website and the court docket. The results of an investigation. Her investigation.

She handed a creased photo to Detective Evans: “100%, that’s him,” she said.

Evans flipped through the pages Sandi had printed out.

The detective noted what prison Thomas was in and his release date: December 2019.

Sandi's words tumbled out: How easy it had been to find him. How he’d raped other women — not just a long time ago, but soon after he’d raped her.

“Five months, almost to the day,” Sandi said haltingly. “Five months ...”

“Um, ’kay,” Evans mumbled.

Why hadn’t Evans told her the case was closed? Sandi asked.

These cases were never really closed, said Evans, they were just moved off her desk to make room for others.

“You have to understand the level of frustration we have at this point,” Gabe said.

“I can understand,” said Evans.

“I don’t think you can,” Gabe said.

“Yes, trust me,” Evans said, her voice rising. “The reason I’m frustrated with you is because you’re. . . . focusing on the negative.”

“It’s been 18 months,” Gabe countered.

“Because I had nothin’, ” Evans shouted.

What she’d had, in fact, was a first name, a phone number, a physical description of the rapist, and the name and phone number of one of his friends.

Gabe told Evans he didn’t like that Sandi had to be her own detective.

“Listen,” Evans responded. “I called Terrance. All I had on Terrance is his name. . . . You know how many Terrances [are] in the world?”

Terrance told Sandi he’d never gotten a call from Evans, or any police officer, about the rape.

And nothing in Sandi’s case file mentioned a call to Terrance. Not Detective Evans’ notes. Not the case summary Evans’ boss signed off on. Not the documents presented to a city prosecutor, who decided there was “insufficient evidence” for charges.

In the detective's skeletal case narrative, she described Sandi as a woman out looking for drugs who’d willingly gone into her rapist’s home. The harrowing story Sandi told, captured in her video interview, never made it onto paper.

“The victim wouldn’t give me the name of her friend who she said gave her this suspect’s phone number,” Evans wrote in her 18-line synopsis of the case.

That wasn’t true.

Gabe and Sandi asked the detective for a timeline. Now that Evans knew the rapist’s full name, what was next?

Evans didn’t give them a straight answer.

Prosecutors might even wait until William Thomas served his current term and got out before tackling the case, she said.

Wouldn’t it be easier to get the guy while he’s locked up? Gabe asked.

“I don’t do their job. I don’t know what they do,” Evans said. “They might say, ‘Well, he’s in jail, f--- it, we’ll get him later. . . I don’t know. I’m just throwing stuff out there."

Evans had some advice: Sandi should stick with her counseling. That way, she’d be strong enough to testify if the case went to court.

Counseling? Sandi wanted to scream. I’ve been going to counseling for almost two years.

After 38 minutes, Evans ushered the couple into the hallway, her demeanor softening. She hugged Sandi.

“Your project is my last project before I walk out of here,” Evans promised. The detective was leaving the unit soon. She told Sandi she didn’t want her to have to tell yet another detective about the rape.

And Sandi didn’t.

She had to tell two.

'Be patient'

It was a ritual now. Sandi would sit in Kate Biddle’s office, surrounded by warm brick walls, and dial the sex crimes unit. She’d put the call on speaker so Kate could listen as she left polite messages for Detective Evans.

“Please, call me back.”

But Evans wasn’t there. Shortly after she met with Sandi and Gabe, the detective left the unit for a new post at the airport. She didn’t tell Sandi.

Evans also didn’t do the things she’d promised. Never finished putting Sandi’s case together. Never took it to prosecutors.

May passed.

June. July. August. September. October.

Sandi kept calling, buoyed by Kate’s support. Some days, just showing up to her appointment was all Sandi could muster.

Kate had spent her career working with traumatized adults and children. In the early 1980s, she was part of the first county children’s services sex abuse unit. At the time, it was considered almost revolutionary. Decades later, after a 17-year-old Chardon student shot and killed three classmates and injured others, Kate led the effort to help children, parents and teachers cope.

She was working at Cleveland's rape crisis center when she first met Sandi. The woman was nearly catatonic. She’d sit in a survivors group with her shoulders hunched, her hands neatly folded in her lap and her eyes on the nearest door.

Being raped hadn’t just stripped Sandi of her sense of control — she’d been held captive, brutalized and made to fear for her life. Kate understood that. The cops ignoring Sandi was making the damage worse — and recovery impossible.

Kate told Sandi it was OK to fight for herself. “This is your right,” she’d remind her. “You have a right to the information about what’s going on with your case.”

But pushing Sandi came with risks. Sandi was newly sober and wanted to stay that way.

Therapists like Kate, and rape crisis advocates embedded in the sex crimes unit, are caught in a conundrum: They have to work within the system to support victims, but some detectives welcome their presence and others don’t, forcing them to tread lightly and limiting their ability to help.

They get a close-up view of the flaws: the overwhelmed detectives, the lack of training, the need for accountability. But it’s not like they have a magic wand to fix it, and the intense work runs them into the ground, too.

That’s what frustrated Kate the most.

“The only thing that ever burnt me out,” she said, “is working with the system.”

Sandi cycled through five victim advocates. But at least a few of them told her when they were leaving.

Finally, in November, a new detective called Sandi. They needed to start over, he said.

“Give me some time,” Detective Morris Vowell said. “Be patient.”

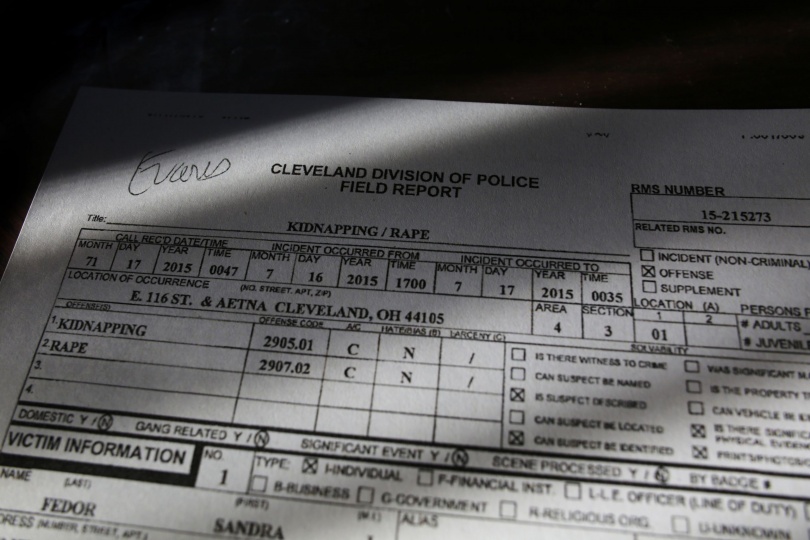

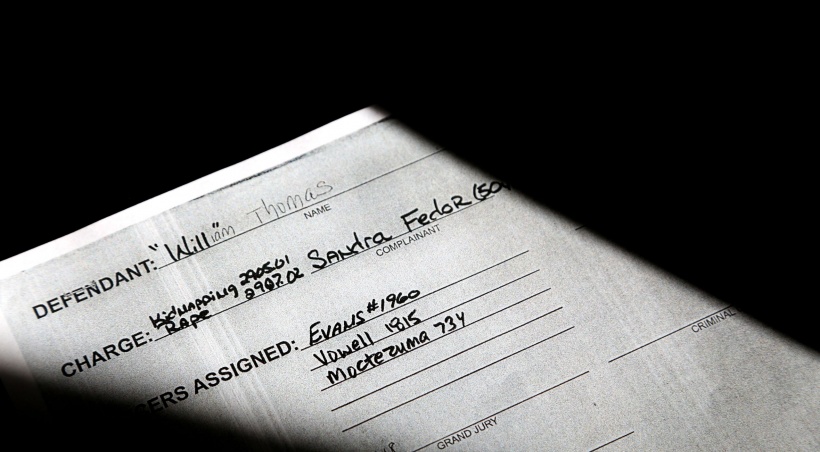

The case file for Sandi's rape shows the names of all three detectives assigned to work on her case.

Schnatter told the detective he needed to get a search warrant to collect William Thomas’ saliva. The lab didn’t find semen in the rape kit, but there was some DNA that could be directly compared. Vowell also needed to interview Thomas.

To do that, he’d have to get permission from a supervisor to make the 3½-hour drive to the Lebanon Correctional Institution or have Thomas brought to Cleveland.

Sandi talked to Vowell in December, and in January. He was still waiting for permission, he told her. In April, it was the same thing.

It seemed so simple, to go and interview a suspect, especially one who was already behind bars. Isn’t that what they do, Sandi thought?

In May 2018, almost a year after Sandi brought her rapist’s full name to Cleveland police, she got a call from another detective.

Detective Vowell had left the unit to pitch in with murder investigations. Homicide was understaffed, though not as much as sex crimes. But the number of unsolved murders was mounting. That, said Mayor Jackson in an August 2017 news conference, was “unacceptable.”

Detective Michael Moctezuma was assigned five cases along with Sandi’s, all from other detectives who’d left. Some of the cases involved children.

I need time to review your file, Sandi remembered her third detective telling her. “Be patient with me.”

- Previous Section

Part 3: How do I find him? - Next Section

Part 5: 'I got a question'