Denied Justice

Brooke Morath barely saw the man who attacked her.

He lunged from the dark early one morning in Minneapolis, blinding her with pepper spray as she scraped snow off her car. Then he tackled her face down onto the frozen ground and raped her.

Bleeding, her eyes burning, Morath staggered to a friend’s house and banged on a window for help, pleading for someone to call 911.

Over the next few hours, the University of Minnesota pre-med student did everything she could to help investigators. She went to the hospital for a sexual assault exam. To preserve possible evidence, she didn’t shower or wash her clothing. When police officers arrived, she answered their questions calmly. An investigator assured Morath that her case was his top priority.

Within days, however, she began to have doubts. She discovered that the police crime alert for her rape listed an inaccurate address. And that officers had missed three nearby businesses while canvassing the neighborhood for surveillance video. Eventually, she said, police stopped returning her calls.

That was two years ago.

Today, Morath has lost hope that police will ever find the man who raped her, and she worries that he is still preying on other women.

“It’s a terrifying, humiliating and defeating feeling,” she said. “It shouldn’t be this hard for a victim.”

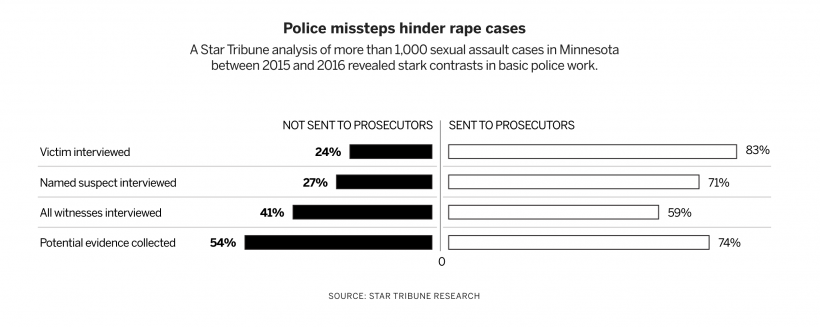

A Star Tribune review of more than 1,000 sexual assault cases, filed around the state in a recent two-year period, reveals chronic errors and investigative failings by Minnesota’s largest law enforcement agencies, including those in Minneapolis and St. Paul.

In almost a quarter of the cases, records show, police never assigned an investigator.

In about one-third of them, the investigator never interviewed the victim.

In half the cases, police failed to interview potential witnesses.

Most of the cases — about 75 percent, including violent rapes by strangers — were never forwarded to prosecutors for criminal charges. Overall, fewer than one in 10 reported sexual assaults produced a conviction, records show.

Victims see it as a stark betrayal.

“I still struggle to feel safe,” said Morath, who is now 24. “Not only because I don’t know the identity of my rapist, but because I don’t trust the law enforcement officer assigned to my case.”

The failure to vigorously investigate sexual assaults is endangering women across Minnesota.

The Star Tribune identified more than 50 cases in which the suspect was someone who had been named, charged or even convicted in a prior sexual assault. Yet these men were rarely arrested when they turned up a second or third time in a police report.

Some committed more assaults before police finally caught up to them.

The 1,000 cases obtained so far amount to about half of all the records sought by the Star Tribune from the 20 law enforcement agencies that reported the most sexual assaults in 2015 and 2016, including Moorhead, Duluth and Mankato. Hundreds of records that were requested months ago have yet to be provided. The request to the Minneapolis Police Department, for example, is now more than a year old. It still has not been completed.

The Star Tribune also asked 13 veteran investigators from across the country to review more than 160 of the Minnesota case files. Combined, they found that police adequately handled just one in five cases.

“If homicides were handled this way, people would be appalled,” said retired Sgt. Elizabeth Donegan, who led sex crimes investigations in Austin, Texas.

In Duluth, a college student reported a rape, then, after hearing nothing for several days, she said she drove to the police station to demand an investigation. She told police there were bloody sheets and a condom at the suspect’s home. Her case was assigned to an investigator, according to Duluth police, but her case file shows no sign that officers ever collected that evidence. Her suspect was never charged.

In Mankato, an 18-year-old woman told police that she had been raped by a 46-year-old man. The suspect told an officer that the sex was consensual, even though the woman was a vulnerable adult who lived in a group home. The police never assigned an investigator, and the case file gives no indication that police ever searched the man’s apartment or collected evidence. An officer wrote, “At this time there are no further known leads to follow for this case,” and suspended the investigation.

Sgt. Richard Mankewich, a former supervisor for the Orange County, Fla., sex crimes squad, reviewed the file and asked, “Seriously, this is the best they can do?”

In Chisholm, a mental health counselor named Katie Finch reported she was raped by a friend after they ran into each other at a popular downtown bar. She said the officer who took her report told her a detective would follow up. No one ever did. Two years later, after the Star Tribune inquired about her case, she said an officer called, apologized and said her case somehow never made it to an investigator’s desk. It has been reopened.

“I felt like I wasn’t important at all,” she said.

Most of the women who spoke with the Star Tribune said police rarely gave them updates on their cases. Finch’s is one of at least five cases reopened by police or prosecutors since the Star Tribune began inquiring about them.

Asked to comment on the Star Tribune’s findings, the head of the Minnesota Chiefs of Police Association said they are “not acceptable.”

“I think there’s no doubt that law enforcement and prosecution … need to look in the mirror and say, ‘what can we do better collectively?’ ” said Andy Skoogman, the association’s executive director.

Skoogman said the cases show how hard it is to hold rapists accountable, but he added that they also show the need for better police training and standards.

Nate Gove, director of the state board that licenses law enforcement officers, said the Star Tribune’s findings concerned him but “were not surprising, given the complexity of these cases.”

Gove also said most law enforcement agencies lack the time and money to fully investigate every case.

“Would I like to see every case fully investigated?” Gove said. “Yes, of course. But we don’t have the resources for that.”

Brooke Morath kept her car at a small parking lot about two blocks from her Dinkytown apartment. She was going to pick up a friend at the Megabus stop when, just after midnight on a Sunday in March 2015, a stranger attacked her.

Minneapolis police responded quickly to the 911 call. Morath recalls Dinkytown being lit up with red and blue flashing lights from squad cars. Officers secured the scene and impounded her car, hoping to find fingerprints or traces of DNA. They searched the icy ground for clues. One officer traced a set of a man’s footprints through the snow.

Taking her to a quiet room in her friend’s house, they questioned her gently, then helped her to an ambulance for a trip to the hospital and a sexual assault exam.

“V1 was crying, shaking and needed assistance standing up,” the officers wrote. “She was bleeding from her nose.”

Later that same day, Morath had a formal interview with the investigator assigned to her case, Sgt. Brian Carlson. She said she answered his questions carefully, but came away feeling that he was just ticking off boxes rather than really listening to her story.

“I was never given the opportunity to provide a complete, uninterrupted narrative,” she said. The interview, she added, felt “interrupted and controlled.”

Donegan, the Texas investigator, agreed. She said the transcript read more like an “interrogation” than a victim interview. She singled out one of Carlson’s questions: “Is everything you’ve told me true and accurate?”

That, Donegan said, “tells the victim right off: You might be lying to me.”

Morath soon developed more doubts about the investigation. Carlson told her he had found nothing useful on surveillance videos from the neighborhood, including one from a Target Express she had passed that night. When she questioned this, they discovered he was looking at the wrong time stamp, she said. The correct one shows a hooded man following Morath down the sidewalk.

Caught on camera

A few days later, she said, at her request, she and Carlson visited three stores directly across from her building to see whether they had surveillance video showing the same thing.

It was too late. The merchants told her they kept surveillance tapes for only 24 hours, and Morath said police hadn’t asked in time.

After that, Morath said, Carlson’s calls grew less frequent and then stopped. Frustrated by the lack of progress, she took the extraordinary step of beginning her own investigation. Using the Target surveillance video, she calculated the height of her suspect and constructed a more accurate timeline of the night’s events. She researched other assaults in southeast Minneapolis, and eventually came across the case of Daniel Drill-Mellum, a former U student accused in two other rapes.

When Morath saw his mug shot, her heart stopped: He looked like the man who had attacked her.

In January 2016, Carlson called to say they had a suspect and were testing his DNA against evidence from her clothing. The match came back negative, and Morath was crushed. But as Carlson described the suspect, she realized the man and his misconduct bore no resemblance to the man who assaulted her, and she urged Carlson to run a DNA test on Drill-Mellum as well.

A month later, Morath said, Carlson called to say that test was negative.

“That was the last time I heard from him about the investigation,” she said.

Without telling Morath, records show, the Minneapolis police stopped investigating her case.

In late 2017, the Star Tribune obtained a copy of Morath’s police file as part of a broad public-records request for closed sex assault cases. Her name, like those of all the victims in the cases reviewed by the Star Tribune, was blacked out. When Morath contacted the Star Tribune about her case and reviewed her file, she learned new details. She saw that a tipster had reported seeing a man resembling her suspect the day after her rape, but that police never called him back. The report also notes that Carlson requested a DNA lab test for Drill-Mellum, but doesn’t say whether the results ever came back.

Morath grew more curious. In March 2018, three years after her rape, she asked the police for a copy of her file.

To her surprise, she said, an officer told her they had just reopened her case — and wouldn’t let her see her records or a copy of the DNA test.

Carlson retired from the MPD in June after 17 years working in sex crimes.

“I’ve investigated hundreds and hundreds of cases,” he said. “I probably spent more time on this case than I did on any other case I worked.”

Carlson recalled the investigation much the way Morath did but said he would have to consult department records to address Morath’s specific concerns. “We really wanted to get the guy and hold him accountable,” he said.

Police and prosecutors say sexual assault can be a difficult crime to investigate. It frequently involves friends, acquaintances or drinking, all of which can cloud the question of consent.

“You often have little or no physical evidence. You have most times no eyewitnesses,” said Jeff Schoeberl, an Anoka County detective and president of the Minnesota Sex Crimes Investigators Association. “Can I convince 12 people unanimously to take the victim’s account?”

Few Minnesota law enforcement agencies require the kind of training that would help officers surmount these challenges.

The International Association of Chiefs of Police has developed a lengthy set of best practices for sexual assault investigations. They include assigning all credible reports to a detective, conducting detailed interviews of the victim and any known suspect, and collecting all potential physical evidence. Convictions are much more likely when police take these steps, according to the Star Tribune’s analysis.

Some states now require that officers who investigate sex crimes complete special training, but Minnesota does not. The Minnesota Peace Officer Standards and Training Board, the agency responsible for setting professional standards, requires law enforcement agencies to have clear, written protocols for a wide range of crimes and situations, including domestic violence and school bus altercations. On sexual assault, the board is silent.

Gove, the board’s executive director, said he would need a directive from the Legislature to require statewide standards for sexual assault investigations.

“I’ve not seen the appetite,” Gove said.

Russell Strand, a former investigator with the U.S. Army, said he was “appalled” by 20 cases he reviewed at the Star Tribune’s request.

“Quite frankly, I am getting frustrated reading them because most are so horrible,” said Strand, now a consultant and trainer in Arizona.

In one Minneapolis case, a teenage girl said she was raped during an after-prom party, that other partygoers saw the assault, and that the suspect later contacted her on social media. According to the investigator’s file, police closed the case without interviewing the suspect or issuing a search warrant for his social media accounts.

“It is beyond me why these investigators are working in this unit,” said Donegan, the Texas investigator.

In a July 2015 case, a woman in Minneapolis reported that a stranger had climbed through a second-floor balcony door one night, cut off her bra and underwear, put a knife to her throat and raped her.

Responding officers found shoe prints on the house and a knife in the front yard, and noted that friends had been on the front porch during the attack. Police never identified or interviewed the friends, according to the case file. They closed the case after a DNA test found no match in the state or national offender registry.

“It looks to me like the MPD either lacked the resources or desire to investigate this terrifying stranger rape of a woman in her home,” said retired Rochester detective Elisa Umpierre. “Shameful.”

Minneapolis police declined to comment on its handling of any specific case but released a statement saying:

Haweyo Shuriye sat on a stoop, her face bruised and bloody, as she told officers about her attack in October 2015. A man she knew had punched and strangled her until she passed out in a friend’s basement in north Minneapolis. She awoke to find herself naked and the man unzipping his pants.

Her file shows that a detective tried unsuccessfully to call her, then sent a letter saying she should call him within two weeks or he would close the case. Shuriye said she never got a call or a letter; she said she didn’t know her case was closed until she spoke with a reporter.

As far as police were concerned, Shuriye had stopped cooperating with the investigation. That happened in about one-third of the cases reviewed by the Star Tribune; in most of them, the police closed the investigation for lack of cooperation.

Some victims drop out because they fear their attacker. Others say they would rather heal and move on.

But high dropout rates can also signal mistakes by the police, said Anne Munch, a former Colorado prosecutor and consultant to the U.S. Department of Justice. Victims, she said, “can feel that their cases are not being thoroughly investigated ... Or they are made to feel like they are the suspect instead of the victim.”

In January 2016, Sarah Ortega called police in Winona and said her ex-boyfriend had raped her the night before. She said he pushed into her home, yanked her hair so hard that she saw stars, struck her on the head and said, “I know you like it rough.”

Ortega said the officer who took her statement asked whether she did like rough sex. Ortega, and a friend who sat with her, both said they felt the officer was casting doubt on her account.

“I felt like I was the one being investigated,” said Ortega, who works at a St. Paul nonprofit and plans to enter graduate school in the fall.

Two officers interviewed the suspect, a student, and wrote that he told them he was carrying a heavy course load and getting good grades. “We encouraged him to focus on that part of his life,” they wrote. “He agreed.” They warned him to stay away from Ortega and forwarded the case to the county prosecutor. The suspect was never charged.

Winona police did not respond to requests for comment.

In November 2016, a St. Paul woman wearing a walking boot and using a cane stopped for a drink after a Minnesota Wild hockey game. As she made her way home, according to her case file, a man dragged her into an alley and raped her as she screamed for help.

The case file shows that a St. Paul investigator interviewed the woman by phone the next day and asked why she hadn’t used her cane to fight the man off. When she said she never thought about it, the officer asked whether she had been drunk.

Asked whether those questions were appropriate, police spokesman Sgt. Mike Ernster said the level of intoxication can help police determine how vulnerable a victim was. “Also,” he said, “investigators want victims to feel empowered and know that hitting the suspect with an object in self-defense would have been appropriate.”

Three months later, the detective left the woman a message saying the lab had found semen in her rape kit and they wanted to test her boyfriend. She never called back. The detective wrote that she couldn’t proceed without the victim’s cooperation.

St. Paul Police Chief Todd Axtell acknowledged recently that his department could improve its handling of sex crimes. In April, following a critical review by Ramsey County Attorney John Choi, Axtell said he would hire two new investigators and send detectives to specialized training. The department is also improving its ability to connect victims with advocates and making new efforts to contact victims who dropped out.

Asked about specific cases reviewed by the Star Tribune, the sex crime unit’s commanding officer, Jim Falkowski, denied that they were mishandled. Falkowski said victims are the department’s top priority, but that sexual assault cases are notoriously difficult to prove.

“We try to serve the victim as best as we possibly can, and sometimes probable cause just does not exist,” he said.

Police assign an investigator to every murder, but that’s not true with rape.

The Star Tribune identified more than 200 cases statewide in 2015 and 2016 where police never assigned an investigator.

Some departments said they lack the resources to pursue cases with weak evidence and little chance of a conviction. But case after case obtained by the Star Tribune show police choosing not to pursue leads even in cases with named suspects or extreme violence.

Amy Johnson, a mortgage auditor, called the Minneapolis police in the fall of 2015 to report that her daughter had been raped a few weeks earlier. The young woman is a vulnerable adult who suffers from severe anxiety and other mental health conditions. She had gone to the house of a man she was dating, and then to his basement. At first, she said, the sex was consensual, but then it turned violent and he raped her anally. Johnson said an officer at the Second Precinct took down the report and told her an investigator would respond soon.

A week passed. No one called.

Finally, Johnson called the sex crimes unit, where she was directed to Lt. Melissa Chiodo. Johnson said Chiodo told her there wouldn’t be an investigation because the unit didn’t have the manpower.

“Won’t you even talk to him?” Johnson recalled asking.

In the police report, Chiodo wrote that she told Johnson: “We can’t talk to people and scare them. Our job is to conduct an investigation and present the facts to secure charges if possible.”

“It was like she meant nothing to them,” Johnson said.

A Star Tribune examination of public records and victim interviews shows that, just two months earlier, another woman had accused the same man of raping her. She, too, said it happened in his basement.

The week after Johnson spoke with Chiodo, the suspect’s ex-wife obtained a restraining order against him. She also accused him of a violent rape.

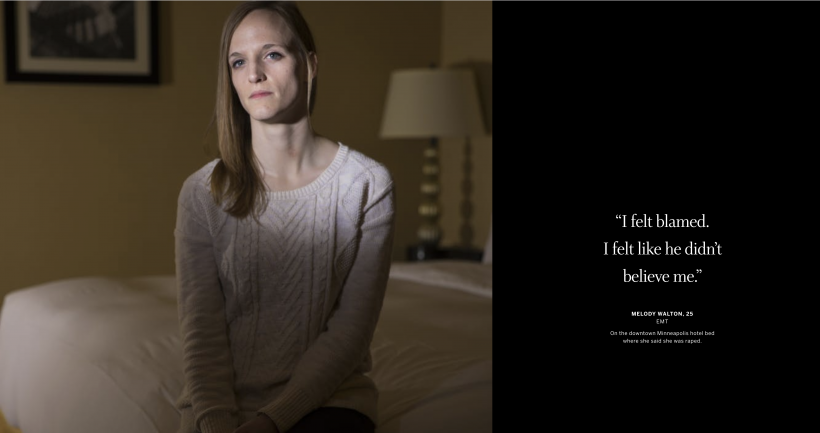

On a Sunday afternoon in August 2016, Melody Walton drove from Albertville, Minn., to the Twin Cities to visit her boyfriend. He had to attend a running clinic that evening, so she went out for a drink at a popular cocktail lounge in northeast Minneapolis.

Walton, who was 23 and training to be an EMT, was sipping a drink and reading “Being Mortal,” Atul Gawande’s book about end-of-life care, when a man sat down beside her. He said he was in town from Florida with a crew that set up concerts. They talked, and he ordered her a few drinks.

When closing time came, Walton told police, she realized she was too drunk to drive. The man offered to drive her car and take her downtown, where she hoped she could sober up at his hotel and wait for her boyfriend.

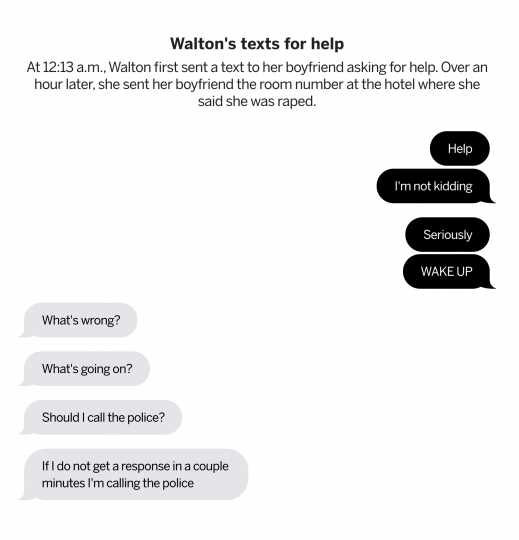

Once in the car, according to the police report, Walton had misgivings and texted her boyfriend for help. She said she had no intention of having sex with the man. A devout Christian, she planned to remain a virgin until she married her boyfriend.

When the man finished, he threw Walton’s clothes at her. She rushed from the room, dialing 911 and taking note of his room number. She ran down 11 flights of stairs and hid in an alley until her boyfriend arrived. They called police and went to the hospital.

When a police officer arrived, Walton said, one of his first questions was: Why were you at the bar drinking alone?

“I felt blamed,” she said. “I felt like he didn’t believe me.”

The police report shows that the officer went back to the hotel, confirmed the suspect’s room number and got his full name. But the report gives no indication that the officer went to the man’s room or tried to interview him. No one from the police got the name of the suspect’s co-worker or talked to him.

Walton said she began blacking out in the car and can’t remember going up to the man’s room. She has a clear memory that one of his co-workers walked in after they arrived, and that the suspect yelled at him to get out. At that point, she told police, she begged him to let her leave. Instead, she said, he raped her for more than an hour.

When the man finished, he threw Walton’s clothes at her. She rushed from the room, dialing 911 and taking note of his room number. She ran down 11 flights of stairs and hid in an alley until her boyfriend arrived. They called police and went to the hospital.

When a police officer arrived, Walton said, one of his first questions was: Why were you at the bar drinking alone?

“I felt blamed,” she said. “I felt like he didn’t believe me.”

The police report shows that the officer went back to the hotel, confirmed the suspect’s room number and got his full name. But the report gives no indication that the officer went to the man’s room or tried to interview him. No one from the police got the name of the suspect’s co-worker or talked to him.

Staff writer Faiza Mahamud contributed to this report.

- Previous Section

- Next Section

Part 2: How Repeat Rapists Slip by Police